The following article on the Cold War policy of containment is an excerpt from Lee Edwards and Elizabeth Edwards Spalding’s book A Brief History of the Cold War It is available to order now at Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

Shortly after Stalin’s death in March 1953, Eisenhower gave a speech notably titled “The Chance for Peace,” in which he made clear that the United States and its friends had chosen one road while Soviet leaders had chosen another path in the postwar world. But he always looked for ways to encourage the Kremlin to move in a new direction. In a diary entry from January 1956, he summarized his national security policy, which became known as the “New Look”: “We have tried to keep constantly before us the purpose of promoting peace with accompanying step-by-step disarmament. As a preliminary, of course, we have to induce the Soviets to agree to some form of inspection, in order that both sides may be confident that treaties are being executed faithfully. In the meantime, and pending some advance in this direction, we must stay strong, particularly in that type of power that the Russians are compelled to respect.”

One of Eisenhower’s first acts upon taking office in January 1953 was to order a review of U.S. foreign policy. He generally agreed with Truman’s policy of containment containment except for China, which he included in his strategic considerations. Task forces studied and made recommendations regarding three possible strategies:

- A continuation of the policy of containment, the basic policy during the Truman years;

- A policy of global deterrence, in which U.S. commitments would be expanded and communist aggression forcibly met;

- A policy of liberation which through political, economic, and paramilitary means would “roll back” the communist empire and liberate the peoples behind the Iron and Bamboo Curtains.

The latter two options were favored by Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, who counseled the use of the threat of nuclear weapons to counter Soviet military force. He argued that having resolved the problem of military defense, the free world “could undertake what has been too long delayed—a political offensive.”

Eisenhower rejected liberation as too aggressive and the policy of containment as he understood it as too passive, selecting instead deterrence, with an emphasis on air and sea power. But he allowed Dulles to convey an impression of “deterrence plus.” In January 1954, for example, Dulles proposed a new American policy—“a maximum deterrent at a bearable cost,” in which “local defenses must be reinforced by the further deterrent of massive retaliatory power.” The best way to deter aggression, Dulles said, is for “the free community to be willing and able to respond vigorously at places and with means of its own choosing.”

As the defense analysts James Jay Carafano and Paul Rosenzweig have observed, Eisenhower built his Cold War foreign policy, largely based on the policy of containment, on four pillars:

- Providing security through “a strong mix of both offensive and defensive means.”

- Maintaining a robust economy.

- Preserving a civil society that would “give the nation the will to persevere during the difficult days of a long war.”

- Winning the struggle of ideas against “a corrupt vacuous ideology” destined to fail its people.

The Eisenhower-Dulles New Look was not, as some have charged, a policy with only two options—the use of local forces or nuclear threats. Covert means were used to help overthrow the pro-Marxist regime of Jacobo Arbenz Guzman in Guatemala in 1954, economic pressures were exerted in the Suez Crisis of 1956, and U.S. Marines were used in Lebanon in 1958. The U.S. Navy was deployed in the Taiwan Straits as part of Eisenhower’s ongoing, staunch commitment to the protection of the Nationalist Chinese islands of Quemoy and Matsu—and by extension the Republic of China itself, Japan, and the Philippines—against communist aggression. With the president’s full endorsement, Dulles put alliance ahead of nuclear weapons as the “cornerstone of security for the free nations.”

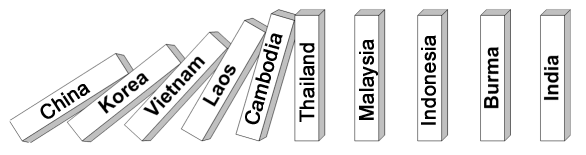

During the Eisenhower years, the United States constructed a powerful ring of alliances and treaties around the communist empire in order to uphold its policy of containment. They included a strengthened NATO in Europe; the Eisenhower Doctrine (announced in 1957, protecting Middle Eastern countries from direct and indirect communist aggression); the Baghdad Pact, joining Turkey, Iraq, Great Britain, Pakistan, and Iran in the Middle East; the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization, which included the Philippines, Thailand, Australia, and New Zealand; mutual security agreements with South Korea and with the Republic of China; and a revised Rio Pact, with a pledge to resist communist subversion in Latin America.

As Eisenhower said in his first inaugural address, echoing NSC 68, “Freedom is pitted against slavery; lightness against the dark.” Like Truman, he believed that freedom—rooted in eternal truths, natural law, equality, and inalienable rights—was the foundation for real peace, and he sharpened the idea that faith in this freedom ultimately united everyone: “Conceiving the defense of freedom, like freedom itself, to be one and indivisible, we hold all continents and peoples in equal regard and honor.”

Dulles, who had closely studied Soviet history and shared Eisenhower’s deep Christian faith, regarded the very existence of the communist world as a threat to the United States and considered the policy of containment as a righteous duty. While George Kennan argued that communist ideology was an instrument not a determinant of Soviet policy, Dulles argued the opposite. The Soviet objective, Dulles said flatly, was global state socialism.

Eisenhower agreed: “Anyone who doesn’t recognize that the great struggle of our time is an ideological one . . . [is] not looking the question squarely in the face.”

The common thread running through all the elements of the Eisenhower strategy—nuclear deterrence, alliances, psychological warfare, covert action, and negotiations—was a relatively low cost and an emphasis on retaining the initiative. The New Look was “an integrated and reasonably efficient adoption of resources to objectives, of means to ends.”

Not all of Eisenhower’s challenges were external— some originated within the borders of the United States and indeed his own Republican party. The most visible and contentious problem was how to deal with the outspoken, unpredictable Senator Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin.

This article is part of our larger collection of resources on the Cold War. For a comprehensive outline of the origins, key events, and conclusion of the Cold War, click here.

This article on the Cold War policy of containment is an excerpt from Lee Edwards and Elizabeth Edwards Spalding’s book A Brief History of the Cold War. It is available to order now at Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

You can also buy the book by clicking on the buttons to the left.

Cite This Article

"Policy of Containment: America’s Cold War Strategy" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

April 17, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/policy-of-containment>

More Citation Information.