The following article on the result of the Cuban Missile Crisis is an excerpt from Warren Kozak’s Curtis LeMay: Strategist and Tactician. It is available for order now from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

In the summer of 1962, negotiations on a treaty to ban above ground nuclear testing dominated the political world. The treaty involved seventeen countries, but the two main players were the United States and the Soviet Union. Throughout the 1950s, with the megaton load of nuclear bombs growing, nuclear fallout from tests had become a health hazard, and by the 1960s, it was enough to worry scientists. Kennedy, in particular, was pushing for a ban and was optimistic about succeeding.

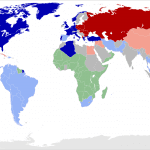

It never happened. The result of the Cuban Missile Crisis was an increasing buildup of nuclear weapons that continued until the end of the Cold War.

Air Force General Curtis LeMay was less sanguine because the U.S. had already been limiting its above ground tests while the Soviets had been increasing their own. Just eight months earlier, on October 31, 1961, the Soviets tested the fifty megaton “Tsar” Bomb, the largest nuclear device to date ever exploded in the atmosphere (the test took place in the Novaya Zemlya archipelago in the far reaches of the Arctic Ocean and was originally designed as a 100 megaton bomb, but even the Soviets cut the yield in half because of their own fears of fallout reaching its population). LeMay did not see any military advantage for the U.S. to sign such a treaty. He doubted the countries would come to an agreement and felt vindicated when the talks deadlocked by the end of the summer. The agreement was ultimately signed the following spring, though, and remains one of the crowning achievements of the Kennedy Administration.

Completely unnoticed that summer was the sailing of Soviet cargo ships bound for Cuba. Shipping between Cuba and the USSR was not unusual since Cuba had quickly become a Soviet client state. With the U.S. embargo restricting Cuba’s trade, the Soviets were propping up the island with technical assistance, machinery, and grain, while Cuba reciprocated in a limited way with return shipments of sugar and produce. But these particular ships were part of a larger military endeavor that would bring the two powers to the most frightening standoff of the Cold War.

Sailing under false manifest, these cargo ships were secretly bringing Soviet-made, medium range ballistic missiles to be deployed in Cuba. Once operational, these highly accurate missiles would be capable of striking as far north as Washington, D.C. An army of over 40,000 technicians sailed as well. Because the Soviets did not want their plan to be detected by American surveillance planes, the human cargo was forced to stay beneath the deck during the heat of the day. They were allowed to come topside only at night, and for a short time. The ocean crossing, which lasted over a month, was horrendous for the Soviet advisers.

The first unmistakable evidence of the Soviet missiles came from a U-2 reconnaissance flight over the island on October 14, 1962, that showed the first of twenty-four launching pads being constructed to accommodate forty-two R-12 medium range missiles that had the potential to deliver forty-five nuclear warheads almost anywhere in the eastern half of the United States.

Kennedy suddenly saw that he had been deceived by Krushchev and convened a war cabinet called ExCom (Executive Committee of the National Security Council), which included the Secretaries of State and Defense (Rusk and McNamara), as well as his closest advisers. At the Pentagon, the Joint Chiefs began planning for an immediate air assault, followed by a full invasion. Kennedy wanted everything done secretly. He had been caught short, but he did not want the Russians to know that he knew their plan until he had decided his own response and could announce it to the world.

Kennedy shared his decision to pursue negotiation and a naval blockade of Cuba while keeping the option of an all-out invasion on the table with the Joint Chiefs on Friday, October 19. The heads of the military, General Earle Wheeler of the Army, Admiral George Anderson of the Navy, General David Shoup of the Marines, and LeMay of the Air Force, along with the head of the Joint Chiefs, Maxwell Taylor, saw the blockade as ineffective and in danger of making the U.S. look weak. As Taylor told the president, “If we don’t respond here in Cuba, we think the credibility (of the U.S.) is sacrificed.”

Of all the Chiefs, Kennedy and his team saw LeMay as the most intractable. But that impression may have come from his demeanor, his candor, and perhaps his facial expressions, since he was not the most belligerent of the Chiefs. Shoup was crude and angry at times. Admiral Anderson was equally vociferous and would have the worst run-in with civilian leadership when he told McNamara directly that he did not need the Defense Secretary’s advice on how to run a blockade. McNamara responded, “I don’t give a damn what John Paul Jones would have done, I want to know what you are going to do—now!” On his way out, McNamara told a deputy, “That’s the end of Anderson.” And in fact, Admiral Anderson became Ambassador Anderson to Portugal a short time later.

LeMay differed from Kennedy and McNamara on the basic concept of nuclear weapons. Back on Tinian, LeMay thought the use of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs, although certainly larger than all other weapons used, were really not all that different from other bombs. He based this on the fact that many more people were killed in his first incendiary raid on Tokyo five months earlier than with either atomic bomb. “The assumption seems to be that it is much more wicked to kill people with a nuclear bomb, than to kill people by busting their heads with rocks,” he wrote in his memoir. But McNamara and Kennedy realized that there was a world of difference between two bombs in the hands of one nation in 1945 and the growing arsenals of several nations in 1962.

Upon entering office and taking responsibility for the nuclear decision during the most dangerous period of the Cold War, Kennedy came to loathe the destructive possibilities of this type of warfare. McNamara would sway both ways during the Cuban Missile Crisis, making sure that the military option was always there and available, but also trying to help the President find a negotiated way out. His proportional response strategy that would come into play in Vietnam in the Johnson Administration three years later was born in the reality of the dangers that came out of the Cuban crisis. “LeMay would have invaded Cuba and had it out . . . but with nuclear weapons, you can’t have a limited war,” McNamara remembered. “It’s completely unacceptable . . . with even just a few nuclear weapons getting through . . . it’s crazy.”

POLITICAL RESULT OF THE CUBAN MISSILE CRISIS

Finally, Nikita Krushchev, who created the crisis, brought it to an end by backing down and agreeing to remove the weapons. As a political officer in the Red Army during the worst of World War II, at the siege of Stalingrad, the Soviet leader understood what could happen if things got out of hand. As his son, Sergei Krushchev, remembered his father saying, “Once you begin shooting, you can’t stop.”

In an effort to help him save face, Kennedy made it clear to everyone around him that there would be no gloating over this victory. Castro, on the other hand was quite different in his response. When he learned that the missiles were being packed up, Castro let loose with a tirade of cursing at Krushchev’s betrayal. “He went on cursing, beating even his own record for curses,” recalled his journalist friend, Carlos Franqui.

There was also a feeling of letdown among the Joint Chiefs. They thought the U.S. had capitulated and, in the end, looked weak. They also did not trust the Russians to stand by their promise to dismantle and take home all the missiles. The Soviets had a long track record of breaking most of their previous agreements. LeMay considered the final negotiated settlement the greatest appeasement since Munich. By breaking his word to Kennedy and placing missiles in the western hemisphere, Krushchev secured the ceremonial removal of the United States’ antiquated medium range missiles from Turkey in exchange for retrieving the missiles in Cuba. It was a hollow gesture as they were scheduled to be removed already, but it allowed Krushchev to save face internationally. Castro continued to be a thorn in the side of the United States. But ultimately, he was mostly inconsequential. More than four decades later, Kennedy’s blockade and negotiated settlement stand as the best-case scenario.

This article is part of our larger collection of resources on the Cold War. For a comprehensive outline of the origins, key events, and conclusion of the Cold War, click here.

|

|

This article on the result of the Cuban Missile crisis is from the book Curtis LeMay: Strategist and Tactician © 2014 by Warren Kozak. Please use this data for any reference citations. To order this book, please visit its online sales page at Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

You can also buy the book by clicking on the buttons to the left.

Cite This Article

"Result of the Cuban Missile Crisis" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

April 24, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/result-of-the-cuban-missile-crisis-2>

More Citation Information.