The following article on the Bay of Pigs Invasion is an excerpt from Warren Kozak’s Curtis LeMay: Strategist and Tactician. It is available for order now from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

In March, just two months into the Kennedy administration, Air Force Chief Curtis LeMay was called into a meeting at the Pentagon with the Joint Chiefs. He would represent the Air Force because White was out of town. LeMay noticed that there was something odd about the meeting right from the start. To begin with, there was a civilian in the room who pushed aside a curtain to reveal landing areas for a military engagement on the coast of Cuba. LeMay had been told absolutely nothing about the operation until that moment. All eyes turned to him when the civilian, who worked for the CIA, asked which of the three sites would provide the best landing area for planes.

LeMay explained that he was completely in the dark and needed more information before he would hazard a guess. He asked how many troops would be involved in the landing. The answer, that there would be 700, dumbfounded him. There was no way, he told them, that an operation would succeed with so few troops. The briefer cut him short. “That doesn’t concern you,” he told LeMay.

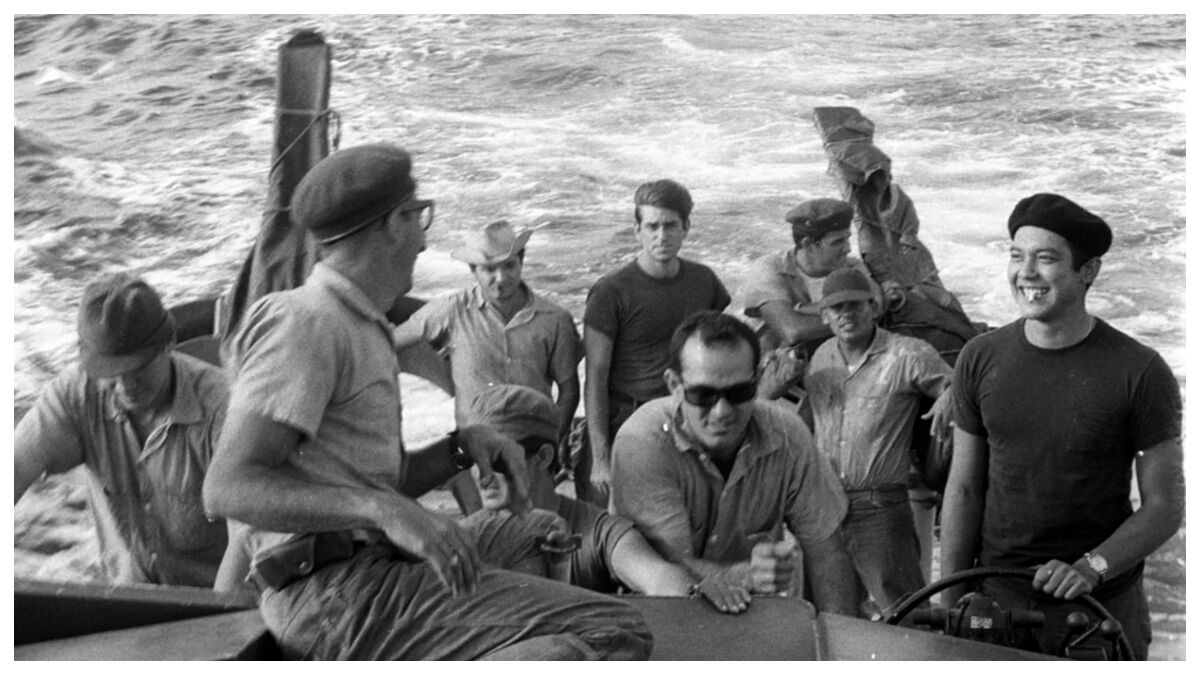

Over the next month, LeMay tried unsuccessfully to get information about the impending invasion. Then on April 16 he stood in for White—again out of town—at another meeting. Just one day before the planned invasion, he finally learned some of the basics of the plan. The operation, which would become known as the Bay of Pigs Invasion, had been conceived during the Eisenhower administration by the CIA as a way to depose Cuban dictator Fidel Castro. Cuban exiles had been trained as an invasion force by the CIA and former U.S. military personnel. The exiles would land in Cuba with the aid of old World War II bombers with Cuban markings and try to instigate a counterrevolution. It was an intricate plan that depended on every phase working perfectly.

THE BAY OF PIGS INVASION: A FAILURE OF MILITARY STRATEGY

LeMay saw immediately that the invasion force would need the air cover of U.S. planes, but the Secretary of State, Dean Rusk, under Kennedy’s order, had cancelled that the night before. LeMay saw the plan was destined to fail, and he wanted to express his concern to Defense Secretary Robert McNamara. But the Secretary of Defense was not present at the meeting.

Instead, LeMay was able to speak only to the Under Secretary of Defense, Roswell Gilpatric. LeMay did not mince words.

“You just cut the throats of everybody on the beach down there,” LeMay told Gilpatric.

“What do you mean?” Gilpatric asked.

LeMay explained that without air support, the landing forces were doomed. Gilpatric responded with a shrug.

The entire operation went against everything LeMay had learned in his thirty-three years of experience. In any military operation, especially one of this significance, a plan cannot depend on every step going right. Most steps do not go right and a great deal of padding must be built in to compensate for those unforeseen problems. It went back to the LeMay doctrine—hitting an enemy with everything you had at your disposal if you have already come to the conclusion that a military engagement is your only option. Use everything, so there is no chance of failure. Limited, half-hearted endeavors are doomed.

The Bay of Pigs invasion turned out to be a disaster for the Kennedy administration. Kennedy realized it too late. The Cubans did not rise up against Castro, and the small, CIA-trained army was quickly defeated by Castro’s forces. The men were either killed or taken prisoner. All of this made Kennedy look weak and inexperienced. A short time later, Kennedy went out to a golf course with his old friend, Charles Bartlett, a journalist. Bartlett remembered Kennedy driving golf balls far into a distant field with unusual anger and frustration, saying over and over, “I can’t believe they talked me into this.” The entire episode undermined the administration and set the stage for a difficult summit meeting between Kennedy and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev two months later. It also exacerbated the administration’s rocky relationship with the Joint Chiefs, who felt the military was unfairly blamed for the fiasco in Cuba.

This was not quite true. Kennedy put the blame squarely on the CIA and on himself for going along with the ill-conceived plan. One of his first steps following the debacle was to replace the CIA director, Allen Dulles, with John McCone. The incident forced Kennedy to grow in office. Although his relationship with the military did suffer, the problems between Kennedy and the Pentagon predated the Bay of Pigs Invasion. According to his chief aid and speechwriter, Ted Sorensen, Kennedy was unawed by Generals. “First, during his own military service, he found that military brass was not as wise and efficient as the brass on their uniform indicated . . . and when he was president with a great background in foreign affairs, he was not that impressed with the advice he received.”

LeMay and the other Chiefs sensed this and felt that Kennedy and the people under him simply ignored the military’s advice on the Bay of Pigs Invasion. LeMay was especially incensed when McNamara brought in a group of brilliant, young statisticians as an additional civilian buffer between the ranks of professional military advisers and the White House. They became known as the Defense Intellectuals. LeMay used the more derogatory term “Whiz Kids.” These were people who had either no military experience on the ground whatsoever or, at the most, two or three years in lower ranks.

In LeMay’s mind, this limited background could never match the combined experience that the Joint Chiefs brought to the table. These young men, who seemed to have the President’s ear, also exuded a sureness of their opinions that LeMay saw as arrogance. This ran against his personality—as LeMay approached almost everything in his life with a feeling of self-doubt, he was actually surprised when things worked out well. Here he saw the opposite—inexperienced people coming in absolutely sure of themselves and ultimately making the wrong decisions with terrible consequences.

This article is part of our larger collection of resources on the Cold War. For a comprehensive outline of the origins, key events, and conclusion of the Cold War, click here.

This article is also part of our larger selection of posts about American History. To learn more, click here for our comprehensive guide to American History.

This article on the Bay of Pigs Invasion is from the book Curtis LeMay: Strategist and Tactician © 2014 by Warren Kozak. Please use this data for any reference citations. To order this book, please visit its online sales page at Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

You can also buy the book by clicking on the buttons to the left.

Cite This Article

"The Bay of Pigs Invasion: Why It Failed" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

April 17, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/the-bay-of-pigs-invasion>

More Citation Information.