This article on Winston Churchill’s childhood is from James Humes’s book Churchill: The Prophetic Statesman. You can order this book from Amazon or Barnes & Noble.

Many of Churchill’s views of politics, warfare, and even international affairs can be traced back to formative views that developed in Winston Churchill’s childhood. He even predicted events that came true decades later.

When contemplating the whole of Churchill’s great career, it is important to look past the most spectacular chapter— his “finest hour” leading Britain in World War II—and recognize that the central issue of Churchill’s entire career was the problem of scale in war and peace. As his letter to Bourke Cockran— written on his twenty-fifth birthday, a few weeks before he escaped from a Boer POW camp—attests, Churchill saw how changes in technology, wealth, and politics not only would create the conditions for “total war” but also would transform war into an ideological contest over the status of the individual.

Churchill was writing to Cockran, a Democratic congressman from New York City, about the economic problem of the “trusts,” which was then front and center in American politics. As we shall see, Churchill had strong views about how governments would need to respond to social changes in the twentieth century—indeed, that question was the focus of his early ministerial career—but from his earliest days, even before he entered politics, he saw that the new scale of things in the modern world would be felt most powerfully in the area of warfare. His observations about the “terrible machinery of scientific war” in The River War led him to ask what would happen when two modern nations—not Britain and the Sudanese Dervishes—confronted each other with the modern weapons of war. It was a question no one else was asking.

Nearly every politician and military commander associated with the 1898 Sudan campaign regarded it as just another in a series of minor military skirmishes or border clashes necessary to maintaining the British Empire in the late nineteenth century. The era of epic continental warfare—of megalomaniacal ambition like that of Napoleon or Louis XIV—was thought to be over. “It seemed inconceivable,” Churchill wrote later in The World Crisis, “that the same series of tremendous events, through which since the days of Queen Elizabeth we had three times made our way successfully, should be repeated a fourth time and on an immeasurably larger scale.”

This was no mere flourish of retrospection. In fact, Churchill himself had first conceived the possibility of intense conflict among the continental powers—occurring in 1914 no less—when he was a schoolboy. It was the first of several astonishing predictions of World War I.

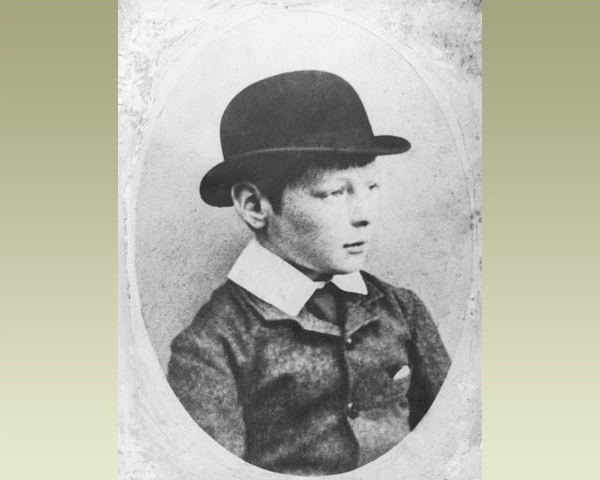

One of the persistent misconceptions of Churchill is that he was a poor student. It is more accurate to say he was, by his own admission, a rebellious student, often bored with the curriculum and chafing under the standard teaching methods of the time. It was obvious from his earliest days in school that he was extremely bright and facile with the English language, a prodigy at learning history and extending its lessons. Still, he was often “on report,” or ranked near the bottom of his class at the end of the term.

One of Churchill’s instructors at Harrow, Robert Somervell, recognized the boy’s abilities. In fact, Somervell thought Churchill ought to attend one of Britain’s prestigious universities rather than the military academy at Sandhurst, where he eventually enrolled. When Churchill was fourteen, Somervell challenged him to write an essay on a topic of his own choosing. He wanted to give his pupil free range to see what his imagination and comprehensive knowledge of history might produce. Churchill’s father, Lord Randolph, had been chancellor of the exchequer, and some speculate that Somervell, expecting an equally illustrious political career for the son, wanted to have a record for the school of Churchill’s early prowess.

Churchill framed his essay as a report of a junior officer from a battlefield on which the British army was fighting Czarist Russia. The date he chose: 1914.

The Engagement of

“La Marais”

July 7th, 1914.

By an Aide de Camp of Gen. C. Officer Commanding H.M. Troops in R.

In his essay, which filled seventeen lined pages, Churchill manifested his knack for map-making and his knowledge of geography. He appended five pages of maps on a scale of two inches to a mile depicting the placement and movement of batteries, trenches, artillery, convoys, tents, and regiments of cavalry and infantry, as well as topography.

Churchill’s essay is a personal, first-hand account of two days of combat, interspersed with personal asides. The aide-de-camp is exhausted after two days: “I am so tired that I can’t write anymore now. I must add that the cavalry reconnaissance party found that there is no enemy to be seen. Now I wish for a good night, as I don’t know when I get another sleep. Man may work. But man must sleep.”

He describes a meeting of the junior officer with senior officers: “Aide-de-camp,” said General C., “order these men to extend and advance on the double.” On another occasion, the general is smashed in the head with a fragment of an artillery shell. Churchill wrote, “General C. observing his fate with a look of indifference turns to me and says ‘Go yourself—aide-de-camp.’”

At times, Churchill’s descriptions of battlefield carnage are suggestive of the American novelist Stephen Crane, who published his classic The Red Badge of Courage a few years later. The astonishing number of men killed in a single encounter foreshadowed the numbers in World War I, a quarter of a century later.

The fields which this morning were green are now tinged with the blood of 17,000 men. . . . Through the veil of smoke—through the stream of wounded—over the corpses, I ride back to our lines in safety.

And a crackle of musketry mixes with the cannonade. Smoke clouds drift and gather on the plain or hang over the marsh. . . . Bang! A puff of smoke has darted from one of their batteries and the report floats down to us on the wind; the battle has begun.

The aide-de-camp reports of his near escape from injury or death when he was dismounted in a clash with Cossack cavalry.

I jumped on a stray horse and rode for my life. Thud! Thud! Thud! And the hoofs of a Cossack’s come nearer and nearer behind me. I glance back—the point of a Cossack’s lance—ahead smoke. The Cossack gains on me. A heavy blow on my back—a crash behind. The thrust strikes my pouch—does not penetrate me. The Cossack has fallen over a corpse.

As might be expected, the English army eventually routs its Russian adversaries. Despite the Czarists’ initial success in a skirmish, the British infantry pushes back their counterparts on the second day of battle.

The enemy retreated slowly and deliberately at first but at the river Volga, they became broken and our cavalry, light and heavy, executed a most brilliant charge which completed the confusion. And thus, the 63,000 Russians fled across the Volga in disorder pursued by 6,000 cavalry and 40,000 infantry.

Churchill concludes with an observation of “the superiority of the English lion over the Russian bear.”

Churchill’s Harrow essay is exhibited today in the underground War Rooms in London, where Churchill managed World War II during the Blitz.

This article is part of our larger selection of posts about Winston Churchill. To learn more, click here for our comprehensive guide to Winston Churchill.

|

This article on Winston Churchill’s childhood is from James Humes’ book Churchill: The Prophetic Statesman. Please use this data for any reference citations. To order this book, please visit its online sales page at Amazon or Barnes & Noble.

You can also buy the book by clicking on the buttons to the left.

Cite This Article

"Winston Churchill’s Childhood" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

April 19, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/winston-churchills-childhood>

More Citation Information.