|

|

|

With Rutherford Hayes declining to run for

a second term, the Republications chose James

A. Garfield as their candidate at the convention

in 1880. Garfield had a long career in the House

of Representatives.

Early Life

James was born in Cuyahoga County, Ohio,

in 1831. Fatherless at two, he was said to be

a dreamer, with his head stuck in novels and

lost in fantasy. He left home at sixteen and

drove canal boat teams, where he fell overboard

fourteen times in six weeks and ended up in

bed seriously ill. His mother persuaded him

that education was valuable, and she scraped

together seventeen dollars to send him to an

academy, where he discovered a lifelong love

of learning. He was graduated from Williams

College in Massachusetts in 1856, and he returned

to the Western Reserve Eclectic Institute (later

Hiram College) in Ohio as a classics professor.

Within a year he was made its president. Garfield

was elected to the Ohio Senate in 1859 as a

Republican. During the secession |

|

| crisis, he

advocated coercing the seceding states back

into the Union, but he did put aside his belief

in pacifism to fight. In 1862, when Union military

victories had been few, he successfully led

a brigade at Middle Creek, Kentucky, against

Confederate troops. At 31, Garfield became a

brigadier general, and two years later he was

a major general of volunteers. Meanwhile, in

1862, Ohioans elected him to Congress. President

Lincoln persuaded him to resign his commission:

It was easier to find major generals than to

obtain effective Republicans for Congress. Garfield

repeatedly won reelection for 18 years, and

became the leading Republican in the House.

A staunch abolitionist before the Civil War,

Garfield became a Radical Republican after Lincoln's

assassination. |

The Election of 1880

In the election of 1880, the Republican

ticket looked like it would boil down to a fight

between former president Ulysses S. Grant and

the more moderate James G. Blaine. Garfield

surprised everyone, however, by earning more

and more votes in the convention balloting.

He won the presidential nomination, and eventually

the election, against Democrat Winfield S. Hancock,

a Civil War hero. The election was the closest

on record. Garfield won by the narrowest of

margins, and only with the help of the New York

political boss Senator Roscoe Conkling, with

whom Garfield had agreed to consult on party

appointments (Conkling had been a prominent

figure in the civil service reform issue because

of his control over appointments to the Port

of New York). Had New York or Indiana gone Democratic,

Garfield would have lost the presidency.

The Garfields

Both James and Lucretia Garfield were devout

members of the Disciple of Christ church. "Crete"

devoted |

|

|

|

herself to raising the Garfield's five

children, all of whom grew up to have rather

distinguished careers. Though she dreamed of

refurbishing the executive mansion, Mrs. Garfield

caught malaria from the swamps behind the White

House before she could begin

the project. Eventually, she enjoyed a complete

recovery and lived to the ripe old age of eighty-six.

Issue: The Economy

Garfield earned a reputation as an expert

on economics while serving in the House. He generally

agreed with the economic reform policies of his

predecessor, although he advocated a return to

the gold standard. Garfield saw the economy as

a moral issue. |

|

Issue: Civil Service Reform

Garfield believed in the idea of civil service

reform in theory, but he had doubts about the

use of merit examinations as a sole criteria for

advancement. Garfield seemed to recognize that

the spoils system supplied necessary money and

workers to the political parties. Only three weeks

into his administration, Garfield allowed Secretary

of State James Blaine to persuade him to nominate

a non-Conklingite as collector of the Port of New

York. Senator Conkling was outraged and he urged

his fellow senators to reject the appointment.

Conkling was losing the fight when he came up

with the idea of resigning from the Senate. His

strategy was that the political machine he controlled

in New York would send him right back with overwhelming

support, and he hoped this show of force would

move other senators to support him. This strategy

backfired, however, as Conkling's followers

deserted him and he was forced into private

life. |

Assassination

President Garfield never had a chance to

press this political advantage. On July 2, 1881,

only four months into his term, Garfield was

shot in the back by Charles Julius Guiteau,

an emotionally disturbed man who had failed

to gain an appointment in Garfield's administration.

Garfield lived for two agonizing months while

doctors failed to find the bullet. Eventually,

he succumbed to blood poisoning. Had Garfield

served his term, historians speculate that he

would have been determined to move toward civil

service reform and carry on in the clean government

tradition of President Hayes. He was also determined

to fight for the civil rights of black Southerners,

as he made clear in his 1881

inaugural address. Unfortunately, he is

best remembered for his assassination. And because

his killer was a frustrated office-seeker, Garfield's

greatest legacy was the impact of his death

on moving the nation to reform government patronage.

Supporters of civil service reform used the

assassination to get some real legislation passed,

the 1883 Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act. |

|

|

|

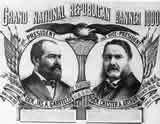

1880 Grand National Republican Banner

|

1881 Engraving of Garfield's Assassination |

"Anything To Keep Him Afloat Till 1884," Puck, January 26, 1881, by Frederick Opper |

"Quixotic Tilting," Puck, May 18, 1881, by Carl Elder von Stur |

"Grant as His Own Iconoclast," Puck, June 15, 1881, by Carl Elder von Stur |

"Struck Down at the Post of Duty," Puck, July 6, 1881 |

"The Czar Getting Up His Little Letter of Condolence to President Garfield," Puck, July 27, 1881, by Frederick Opper |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|