|

|

|

Early

Political Career

In 1884, Grover Cleveland was the first Democrat

to be elected president since the Civil War. He

was also the second, elected again in 1892 after

the White House had returned to Republican rule

for four years in the 1888 election. Cleveland

is generally considered one of the more important

presidents between Abraham Lincoln and Theodore

Roosevelt. Although Cleveland often indulged in

negativity, part of his perceived success was

in his firmness in not allowing the government

to do harmful things to the country.

Grover Cleveland emerged from humble origins

in New Jersey and New York. An uncle paid for

him to study law, and Cleveland passed the bar

exam at the age of twenty-two. Cleveland became

active in politics as a Democrat, having been

elected country sheriff, and mayor of Buffalo.

In 1882, Cleveland used his popularity |

|

| and reputation

as an honest man to successfully run for state

governor. During the next two years, he continued to use his authority to fight against corruption

and waste. Governor Cleveland used his power

to take on the New York City-based political

machinery known as Tammany Hall, even though

this group had supported him in the election.

A big man of 280 pounds, Cleveland, was affectionately

nicknamed "Big Steve" and even "Uncle

Jumbo." In 1884, Cleveland was nominated

to be the Democrat Party's candidate for the

presidency. |

The

Election of 1884

In the election of 1884, Cleveland appealed to

middle class voters of both parties as someone

who would fight political corruption and big-money

interests. Cleveland had the popularity to carry

New York, a state crucial to Democratic victory.

Luckily, Cleveland's Republican opponent, James

G. Blaine, was seen by many as a puppet of Wall

Street and the powerful railroads. The morally

upright Mugwumps, a group of reform-minded businessmen

and professionals, hated Blaine, but supported

Cleveland for his attempts to battle railroad

giant Jay Gould. Ever since 1868, presidential

candidates had relied on a strong Civil War resume

to help win popular approval. The election of

1884 marked a departure from this, as both Cleveland

and Republican candidate James G. Blaine has taken

advantage of a provision in the draft law that

allowed for the hiring of a substitute. But Cleveland

had a sex-scandal to live down. Maria Halpin accused

Cleveland of fathering her son out of wedlock,

a charge that he admitted might be accurate, since

he had had an affair with Halpin in 1874. Cleveland

admitted to paying child support in 1874 to Halpin,

but she |

|

|

| was involved with several men at the time,

including Cleveland's law partner and mentor,

Oscar Folsom, for whom the child was named. (Cleveland

may not have been the father and is believed to have assumed responsibility because he

was the only bachelor among them.) By honestly confronting

the charges, Cleveland retained the loyalty of his supporters,

winning the election by the narrowest of margins. After

Cleveland's election as President, Democratic newspapers

added a line to the chant used against Cleveland during

the campaign and made it: "Ma, Ma, where's my Pa?

Gone to the White House! Ha Ha!" [1885

inaugural address]. |

|

Marriage

After his first two years in office as a bachelor

president, Cleveland announced his marriage

to his twenty-two-year-old ward, Francis Folsom,

the daughter of his former law partner. The

press had a field day satirizing the relationship

between the old bachelor and the recent Wells

graduate, who quickly became the most popular

first lady since Dolly Madison. Frances adhered

to the prevailing ideal that separated the private

lives of women from the public lives of men.

Respecting the wishes of her husband, she never

used her popularity to advance the political

causes of her day, such as social reform and

women's suffrage.

Philosophy

Grover Cleveland believed strongly in a limited

government. He was especially against the government

providing paid to citizens in need for fear

that such aid would weaken the national character.

As he said at the |

|

time that he vetoed a bill

that would have provided relief for drought-stricken

farmer, "the lesson should be constantly

enforced that though the people should support

the government, the government should not support

the people."

Issue: Labor

This attitude extended to Cleveland's stand on key

labor issues of the time. Cleveland's two terms encompassed

several of the more infamous events in labor history.

There was the 1886 general strike when workers demanded

an eight-hour workday that resulted in the brutal

Haymarket Riot in Chicago, followed a few years labor

in the Pullman strike of 1894, when Cleveland used

federal troops to end a train boycott organized by

Eugene V. Debs.

Issue: The Economy

At the end of 1887, Cleveland called for a reduction

in tariffs, arguing that high tariffs were contrary

to the American ideal of fairness. Cleveland would

later campaign on this issue for reelection in 1888.

His opponents argued that high tariffs protected US

businesses from foreign competition and Cleveland

lost that election. Cleveland would be back again

in 1892 for another four years. In 1888, when Cleveland ran for reelection,

the Republicans spent lavish funds to insure victory

for their candidate, Benjamin Harrison, raising three

million dollars from the nation's manufacturers. This

marked the beginning of a new era in campaign financing.

Again, New York was the deciding factor, and Harrison

carried the day.

In 1892, however, after four years

of Republican leadership, Cleveland won against Harrison,

who had alienated ethnic voters in the Midwest, possibly

due to his support for temperance. Cleveland became

the only president to come back from defeat and be reelected

after losing the office. |

| |

|

c.1884 Grover Cleveland Coat Button

|

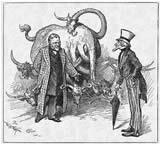

"What Are The Wild Waves Saying, Sister?", Puck, October 1, 1884, by Bernard Gillam |

"Between Scylla and Charybdis," Puck, November 26, 1884, by F. Graetz |

"The Knight of the Wind-Bag Enters The Senatorial Field," Puck, December 31, 1884, by Bernard Gilliam |

"Grand Triumph of Brains Over 'Boodle'!," Puck, January 28, 1885, by Bernard Gillum |

"How Do They Like It Themselves?", Puck, February 11, 1885, by Bernard Gillum |

"The Old Lion and The Ass," Puck, February 25, 1885, by Bernard Gillum |

"The Cruel Secretary of the Navy and the Patriotic Contractor," Puck, April 1, 1885, Eugene Zimmerman |

"Consistent Civil Service Reform," Puck, April 8, 1885, by Frederick Opper |

"The World's Plunderers," Harper's Weekly, June 20, 1885, by Thomas Nast |

"A Flirtation That May Lead To Serious Results In The Fall," Puck, July 29, 1885, by Frederick Opper |

"A Petty Annoyance," Puck, August 5, 1885, by Eugene Zimmerman |

"The Only Plumber Busy In The Hot Season," Puck, August 19, 1885, by Eugene Zimmerman |

"Two Retired Bar'ls," Puck, October 7, 1885, by Eugene Zimmerman |

"The Rival Sand-Which Men," Puck, October 28, 1885, by Eugene Zimmerman |

"At It Again," Puck, November 18, 1885, by Eugene Zimmerman |

"It Works Both Ways," Puck, November 25, 1885, by Eugene Zimmerman |

"'Change About'--The Monkey The Master," Puck, December 23, 1885, by Bernard Gillum |

1886 Painting, The Strike, by Robert Koehler |

"Her Resolute Opposition," Puck, February 10, 1886, by G.E. Ciani |

"Innocents Abroad," Puck, September 29, 1886, by Frederick Opper |

Sheet Music: "Kansas City Exposition March" (1887) |

"The Senate of the Future--A Close Corporation of Millionaires," Puck, January 19, 1887, by Frederick Opper |

"The Medium and His Dupes," Puck, April 6, 1887, by Frederick Opper |

"Public Office Is a Public Trust," Harper's Weekly, June 20, 1885 |

"On The Sly," Puck, April 4, 1888, by Frederick Opper |

"The Two Silly Billies and The Hard Stone Wall," May 16, 1888, by Frederick Opper |

"The Bigger The Bar'l, The Smaller The Man," Puck, June 20, 1888, by Frederick Opper |

"It Won't Do," Puck, August 15, 1888, by Frederick Opper |

"A Trustworthy Beast," Harper's Weekly, October 20, 1888, by William A. Rogers |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|