|

|

The election of 1896 is seen as the beginning of a new era in American politics, or a "realignment" election. Ever since the election of 1800, American presidential contests had, on some level, been a referendum on whether the country should be governed by agrarian interests (rural indebted farmers--the countryside--"main street") or industrial interests (business--the city--"wall street"). This was the last election in which a candidate tried to win the White House with mostly agrarian votes.

Although there were several important issues in the 1896 election, the nominating process was dominated by the fallout of the country's monetary policy, an issue that had been at the forefront of American politics for decades, but had come to a head |

|

|

| during Grover Cleveland's second administration. The economic depression of 1893 and the Democratic Party's response to the crisis had resulted in major Republican gains in the House in the 1894 midterms, as well as heightened prospects for 1896. Cleveland had achieved his goals,

but in doing so had also split the Democratic Party over fiscal policy.

Some Democrats agreed with Cleveland's support of the gold standard. These conservative Democrats became known as "gold bugs". More rural, populist Democrats believed that inflation was the key to raising prices and easing the debt of the farmers. They advocated "free silver"--the unlimited coinage of silver at a ratio of 16 to 1 against gold coins. These populist "silverites" had made significant gains within the Democratic Party in the 1894 midterm elections, despite overall party losses. 1894 would turn out to be the peak of the populist influence, though that would only become clear in retrospect. In the presidential election year of 1896, the split set up a fascinating political election season. |

|

The "free silver" campaign was aided in large part by the publication in 1894 and 1895 of a booklet called, Coin's Financial School. Through the educational teachings of fictional Professor Coin, the booklet extolled the sound financial decisions made by the founders, when in 1792 Congress fixed the monetary unit of one dollar at 371.25 grains of silver. Gold was also made money, but its value was pegged to the silver dollar at a ratio of 15 to 1, and then 16 to 1. Although this was called bimetallism, it was actually a silver standard. Silver fixed the unit and the value of the gold was regulated by it. This was wise, according to Coin, because silver was scattered among the people, and one person could not so easily injure the economy by monopolizing the metal as he could with gold. Professor Coin further explains such concepts as credit money (paper, coins, etc.), all of which were redeemable in redemption or "primary" money (gold, silver) to which a stable value had been given. A greenback system could also be employed, as long as the amount of money in circulation was |

|

| limited per capita so that it could be redeemed at any given time and confidence in the government's ability to do so could be maintained. But then, Congress perpetuated what Professor Coin called "The Crime of 1873." It repealed the unit clause of 1872 and replaced the language with this: |

That the gold coins of the United States shall be a one-dollar piece which

at the standard weight of twenty-five and eight-tenths grains shall be the

unit of value.

|

| The right to free silver was denied, and silver was no longer legal tender in the payment of debts over $5. With this law, the supply of primary money was cut in half. Because there was a very limited gold supply, all property declined in value in comparison to gold (or gold increased dramatically in value and buying power). Borrowing became the only way to pay outstanding debts, even as falling prices continued because there was not enough real money behind the credit money. Mounting debts and mortgages had created the panic of 1893. |

| And there were international implications. The United States had followed England's example of 1816 by abandoning silver, but many other nations quickly followed America. As the demand for gold increased, so did its purchasing power, and prices declined. And all of this, according to Professor Coin, had been arranged by London. Having cornered the gold market, the British wanted America's large Civil War debt to by paid in gold. The U.S. was paying England $200 million annually in gold just for the interest on the nation's debt, but in doing so were sacrificing $400 million in property that was required to secure the $200 million in gold, mostly at the expense of the farmer. Written by William Hope Harvey, Coin's Financial School sold hundreds of millions of copies, and perpetuated the belief that America's economic hard times was the result of a national and international conspiracy against silver. |

|

|

| |

| Following a series of successful election cycles and a split in the Democratic Party, Republicans had good reason to be excited about their prospects for retaking the White House in 1896. With former President Benjamin Harrison and Ohio Senator John Sherman declining to run, the main candidates seeking the nomination were Speaker of the House Thomas B. Reed of Maine, Senator William Allison of Iowa, and Governor William McKinley of Ohio. William McKinley was the overwhelming favorite, another in a series of Republican

candidates who came from Ohio, reflecting the

growing political clout of the American Midwest.

He was a congressman and then governor of the

state, and even had a distinguished Civil War

record, which was still a political asset more

than three decades after the war had ended. McKinley

had a friendly demeanor, was a devout Methodist,

and was motivated by a strong and sincere sense of

morality. One of the most powerful political themes of

the late-nineteenth century Republican Party

was American nationalism. For some Republicans,

nationalism was best expressed by continuing

to push the moral high ground of the Civil War

era, or to raise fears about Papists (Catholics) or immigrants,

or the social calamities caused by alcohol consumption. |

|

|

|

McKinley, however, was able to focus the Republican

Party's nationalist creed on the need for protective

tariffs. Though McKinley had suffered politically

in the early '90s for this stance, by 1896 the

Republican Party was ready to present itself

as standing behind the farmer, the rising middle

class, and the Protestant industrial worker

through high taxes on foreign imports. McKinley had also skillfully avoided the money question. This would turn out to be an important asset in an election where the opposition focused almost entirely on the issue.

To run his campaign, McKinley allied himself with Mark Hanna, an Ohio industrialist with middle class origins who had become quite wealthy as a shipper and broker serving the iron and coal industries. Hanna, who was fascinated more by politics than profits, transitioned to running campaigns for prominent Ohio candidates. He had unsuccessfully backed Senator John Sherman for the Republican nomination at the |

|

1888 convention, but did help McKinley win two terms as governor. Earlier in the year, Hanna had shrewdly sized up both Sherman and McKinley, and had concluded that McKinley would be the better candidate. Hanna's convention strategy had been to win the nomination by promising patronage to powerful political bosses like Thomas Platt of New York and Matthew Quay of Pennsylvania, but McKinley vetoed the strategy in favor of the slogan, "The People Against The Bosses." By the time the convention began, McKinley was already the clear favorite, and he won on the first ballot. Garret Hobart, a businessman and state politician from New Jersey, was nominated for vice president in the hopes that he would help his party carry his home state for the first time since 1872.

The Republican Party platform adopted at the convention was extremely critical of President Cleveland and |

|

|

| congressional Democrats, blaming them for all of the economic woes, and for damaging the image of America abroad. A high protective tariff was emphasized, in conjunction with reciprocal trade agreements with other nations. Other foreign policy positions included support for the annexation of Hawaii, and the creation of a transoceanic canal through Nicaragua, controlled by the United States. Additionally, the platform expressed sympathy for Armenians suffering under Turkish repression, and for Cuban freedom fighters struggling against the Spanish. On the domestic front, Republicans supported pensions for Union veterans and economic opportunities for women (without mentioning suffrage), and opposed anti-Black activities in the South. As for the money questions, the Republicans supported the gold standard and explicitly rejected free silver unless it were allowed under international agreement, which was extremely unlikely. The platform's monetary policy did cause the walkout of 21 free silver delegates, but otherwise was universally supported. |

| |

Following the depression of 1893 and significant losses in the presidential midterms as well as state and local elections in 1895, the Democratic Party had split. In early 1895, Congressman Richard ???Silver Dick??? Bland of Missouri and William Jennings Bryan of Nebraska, a former congressman (1891-1894), led the revolt against President Cleveland. They argued that Cleveland's economic policies did not represent the party???s mainstream support of free silver.?? Bryan promoted a statement signed by 31 House Democrats urging Democrats to become the party of free silver.?? That summer, Bryan conducted a successful speaking tour in the Midwest and South. He attacked the ???money power??? in Washington and called for new party leadership.?? Silver Democrats attempted to take control of the party's national organization, but Bryan worked alone to build a national free silver coalition of Democrats, Republicans, and Populists. The country entered the 1896 political season with Cleveland barely able to maintain control of his party. In the spring of 1896, free silver Democrats won control of many of the state delegations to the national convention, but Democrats arrived at their convention in Chicago without a clear choice for the nomination. Congressman Richard P. Bland of Missouri was a leading candidate, but Populists were hoping for a more free silver candidate, and they were opposed to his wife's Catholicism. Former Congressman William Jennings Bryan had taken advantage of the attention his work the previous year had earned him, and began writing delegates for support that spring. Although some delegates from the West and the South intended to vote for him, a pre-convention poll just two days before the convention's opening ranked him last among seven candidates. On July 7, the convention opened with silverites establishing clear control. They eliminated two candidates and adopted a free silver plank that had been written by Bryan.

Of the remaining men, Bryan maneuvered to be the last to speak in the platform debate on July 9. He claimed to speak ???in defense of a cause as holy as the cause of liberty???the cause of humanity.????? Bryan blamed the gold standard for impoverishing Americans, and identified agriculture as the foundation of American wealth.?? He called for reform of the monetary system, an end to the gold standard, and promised government relief efforts for farmers and others hurt by the economic depression. Bryan ended his rousing oration with religious imagery:

Having behind us the producing masses of

this nation and the world, supported by the

commercial interests, the laboring interests

and the toilers everywhere, we will answer their

demand for a gold standard by saying to them:

You shall not press down upon the brow of labor

this crown of thorns, you shall not crucify

mankind upon a cross of gold.

|

| The convention was momentarily stunned, but then broke into celebratory pandemonium. The speech, forever after known as the "Cross of Gold" speech, had been so dramatic that after he had finished many delegates carried him on their shoulders around the convention hall. Voting began the next morning, on July 10. Congressman Bland led on the first three ballots, but could not garner the requisite two-thirds majority. Each time, Bryan gained in strength. He took the lead on the fourth ballot, and finally won the nomination on the fifth. The next day Arthur Sewall was nominated as Vice President. It was hoped that the inclusion of the pro-protectionist, free silver shipbuilder and banker |

|

|

|

from Maine would appease the business community who were nervous about Jennings, and that the wealthy running mate would contribute financially to the campaign. At age 36, Bryan became the youngest candidate ever nominated for the presidency of the United States. Some Democrats broke with the mainstream party. Some in the Northeast privately and even publicly supported the Republican ticket, while some in the Midwest formed their own party, the National Democratic Party.?? In early September, the breakaway faction convened in Indianapolis, where they nominated Senator John Palmer of Illinois for president and Simon Bolivar Buckner, a former Confederate general and governor of Kentucky (1887-1891), for vice president. |

|

|

| |

| The Populist Party grew out of the agrarian discontent of the 1890s, especially in the South and West of the Mississippi River. It grew out of the Farmers' Alliance, whose main goal since 1876 had been to achieve economic reform in railroad and brokerage rates. By 1896, following the Panic of 1893, the party had become almost exclusively identified with the free silver movement. The inclusion of Populist positions in the Democratic Party's platform caused a split in the Populist Party. Some Populists, called "fusionists," wanted to join the Democrats. The more radical "mid-roaders" wanted to remain a separate organization and pursue a larger agenda. At their convention in St. Louis, the Populists passed a wide-ranging reform platform and then nominated Bryan for president. The mid-roaders started an anti-Bryan protest, but it was cut short when the lights were turned on. They did succeed in opposing Bryan's running mate on the Democratic ticket, Arthur Sewall (he was seen as too anti-labor), and instead nominated Thomas E. Watson, a former Populist congressman from Georgia. Watson refused to campaign for Bryan. |

| |

|

| Throughout the history of the United States, it had been tradition that presidential candidates did not actively campaign for their election. Some had made brief speaking engagements, but it was considered undignified for a candidate to actively campaign on his own behalf. Instead, party loyalists made the pilgrimage to the candidate's house, where they camped out on the front lawn, hoping for a glimpse of the candidate. Usually the candidate would give a mid-afternoon speech from his front porch, giving name to the "front porch campaign." This tradition had begun to erode prior to 1896. James Blaine had spent six weeks campaigning. William Jennings Bryan became the first presidential candidate to spent nearly the entire campaign season on the campaign trail. He did so largely out of necessity, being outspent and out-organized by the Republicans. But Bryan was an impressive and effective speaker. By taking his message directly to the people in an age that still considered political speeches high entertainment, Bryan was able to personify the free silver cause with enormous energy, and keep the campaign focused on the monetary issue, rather than on the tariff, which Mark Hanna had assumed would be the main issue. Bryan traveled to twenty-seven states, but focused largely on the midwest, where he believed the deciding battleground to be. He traveled, by his own account, 17,909 miles and made nearly 600 speeches. Bryan even traveled through Michigan's Upper Peninsula in his four-day swing through the state from October 14-17. On the 15th, Bryan gave speeches to his largest crowds in Traverse City, Big Rapids, |

and Grand Rapids (3 speeches), but that was nothing compared to what he accomplished the next day. In his book The First Battle (1896), Bryan writes:

Friday was one of the long days. In order that the reader may know how much work can be crowded into one campaign day, I will mention the places at which speeches were made between breakfast and bedtime: Muskegon, Holland, Fennville, Bangor, Hartford, Watervliet, Benton Harbor, Niles, Dowagiac, Decatur, Lawrence, Kalamazoo, Battle Creek, Marshall, Albion, Jackson (two speeches), Leslie, Mason, and Lansing (six speeches); total for the day, 25. It was near midnight when the last one was finished. |

|

|

Bryan did touch on other planks from the Democratic platform, but it was the free coinage of silver that he pushed most.?? Bryan argued that agriculture was the backbone of society, that it was absolutely essential for it to be healthy in order for the industrial centers of the country to also prosper.?? The Democrats wanted the inflation that would

result from the silver standard. They believed

higher inflation would make it easier for farmers

and other debtors to pay off their debts by

increasing their revenue dollars. It would also

reverse the deflation which the U.S. experienced

from 1873-1896, a period historians now refer to as the Long Depression (it was called The Great Depression until 1929). Bryan also argued that free silver would provide more money for industrial expansion and job creation.?? At its core, the free silver agenda was an argument to redistribute wealth and power from the few to the many.?? Along the way, Bryan also sought the votes of the average working man. He condemned court-ordered injunctions against strikers, like the one employed by President Cleveland against the Pullman strikers, and he endorsed a progressive federal income tax. Unfortunately for Bryan, however, both of these positions were at odds with Supreme Court decisions handed down the previous session.

By October, newspapers that supported Bryan began to change tactics. They began to focus on the man they saw as holding McKinley's puppet strings--Mark Hanna. For weeks, editorial cartoons savaged Hanna as a bloated plutocrat who had McKinley completely under his thumb. |

|

| |

William McKinley shown as being in the palm of Mark Hanna's Hand, New York Journal, 1896, by Davenport

|

"I Am Confident The Workingmen Are With Us," New York Journal, October 8, 1896. by Homer Davenport |

"Honest Money," New York Journal, September 12, 1896, by Davenport |

"'It Is Legal To Starve, But Not To Murder'--Or, Mark Hanna's Idea of Humor," New York Journal, October 13, 1896, by Homer Davenport |

WILLIAM J. BRYAN: "You Shall Not Press Down Upon the Brow of Labor This Crown of Thorns." St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 22, 1896, by William Allen Rogers |

|

| |

|

|

By contrast, William McKinley conducted a traditional "front

porch campaign," receiving visitors at

his home in Canton, Ohio. Behind the scenes, however, the Mark Hanna machine went into high gear. By charging the Democratic Party as supporting both Populist and Socialist agendas, such as government ownership of communication and transportation businesses, Hanna effectively frightened

American businessmen into donating $3.5 million dollars to the campaign, five times more than Bryan raised. Hanna pumped

the money into an effective propaganda machine.

Evoking the attitudes of the time toward gimmicky

quack medicine, Theodore Roosevelt said of Hanna's

efforts, "He has advertised McKinley as

if he were a patent medicine!" Hanna also engineered a masterful response to Bryan's Cross

of Gold Speech. The Republicans combined the bimetallism issue with the tariff question and promised a return to prosperity,

social order, and morality. They argued that inflation |

|

| caused by free coinage

of silver would create a "53-cent dollar"

that would rob the workingman of his buying power. They also argued that uncontrollable inflation would put a burden

on creditors, such as banks, whose loans' interest rates

would then fall lower than the inflation rate and garner

a loss for the creditor. Hanna also sent nearly 1500 speakers on the campaign trail to attack Bryan, most notably Theodore Roosevelt, who denounced Bryan as a dangerous radical. Hanna flooded the country with an estimated 250 million pieces of campaign literature (published in various languages) so that at times each American home was receiving pro-McKinley material on a weekly basis. The culmination of the campaign was a decree, issued by Hanna, that November 2 would be designated Flag Day for Republicans, who were expected to "assemble in the cities, villages, and hamlets nearest their homes and show their patriotism, devotion to country and the flag, and their intention to support the party which stands for protection, sound money, and good government." [New York Times, October 27, 1896, page 2]. The suggestion was that McKinley was only true choice for patriotic Americans. |

Bryan pro-silver and McKinley pro-gold campaign badges (5 views)

|

"He Must Be Kept Out", Puck, 1896. by Joseph Keppler |

"You Shall Not Press Down Upon the Brow of Labor This Crown," Harper's Weekly, September 5, 1896, by William Allen Rogers

|

"The Sacrilegious Candidate," Judge, September 19, 1896, by Grant Hamilton |

"The Real Issue," Republican Campaign Poster

|

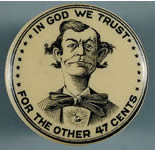

Republican Anti-Bryan Campaign Button referencing the "53 cent dollar"

|

"Buncombe and Boodle," Puck, 1896, by Louis Dalrymple |

McKinley Campaign Anti-Free Silver Bullion Coinn |

McKinley Campaign Anti-Free Silver Dime |

|

|

| |

On November 3, 1896, 14 million American voted. McKinley won with 276 electoral votes to Bryan's 176, [1896 electoral map] and by a popular vote margin of 51% to Bryan's 47%. Bryan did well in the South and the West, but lacked appeal with unmortgaged farmers and especially the eastern urban laborer, who saw no personal interest in higher inflation. Hanna's "McKinley and the Full Dinner Pail" slogan had been more convincing. McKinley won in part by successfully forging a new coalition with business, professionals, skilled factory workers and prosperous (unmortgaged) farmers. By repudiating the pro-business wing of their party, the Democrats had set the stage for 16 consecutive years of Republican control of the White House, interrupted only in 1912 when a split in the Republican Party aided the election of Woodrow Wilson.

[1897

inaugural address]. Once in office, McKinley followed through on his proposed

economic policy, |

|

|

| carefully moving the country

toward the gold standard while establishing

a protective trade policy. By 1898, renewed

economic prosperity would be threatened by the

greatest foreign policy crisis since the War

of 1812, a war with Spain. |

| |

"Thanksgiving," Puck, November 25, 1896, by Louis Dalrymple

|

"Good-Bye and Good Luck," Judge, March 6, 1897, by Grant Hamilton |

"Papa's Pet," Puck, April 7, 1897, by Louis Dalrymple |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|