The Background of Battle of Antietam

Battle of Antietam-Having liberated most of the Old Dominion, Lee took his troopers on a campaign into Maryland, with his eyes on Pennsylvania, hoping to draw out another Union army and defeat it. This was an election year, and if Lee could bring Confederate troops to Maryland and Pennsylvania, perhaps Northern voters would return a congressional majority that would recognize Southern freedom.

Lee issued a proclamation as his army crossed into Maryland—a state where Lincoln had suspended habeas corpus and imposed martial law —emphasizing that the South stood for the principle of freedom, free association, and tolerance. In contrast to Pope’s threats against Southern civilians, Lee’s proclamation said: “No constraint upon your free will is intended: no intimidation will be allowed within the limits of this army, at least. Marylanders shall once more enjoy their ancient freedom of thought and speech. We know of no enemies among you, and will protect all, of every opinion. It is for you to decide your destiny freely and without constraint. This army will respect your choice, whatever it may be; and while the Southern people will rejoice to welcome you to your natural position among them, they will only welcome you when you come of your own free will.”

Lee’s troops were vulnerable, traveling in Federal territory, and in one of the great turning points of the war, Union troops found three cigars wrapped in a sheet of paper. The paper was a duplicate of Lee’s Special Orders No. 191 belonging to one of General D. H. Hill’s staff officers. The orders were delivered to McClellan, who now knew not only Lee’s entire plan of maneuver, but recognized how dangerously divided were Lee’s forces. “Here is a paper,” exclaimed Little Mac, “with which if I cannot whip Bobby Lee I will be willing to go home.”

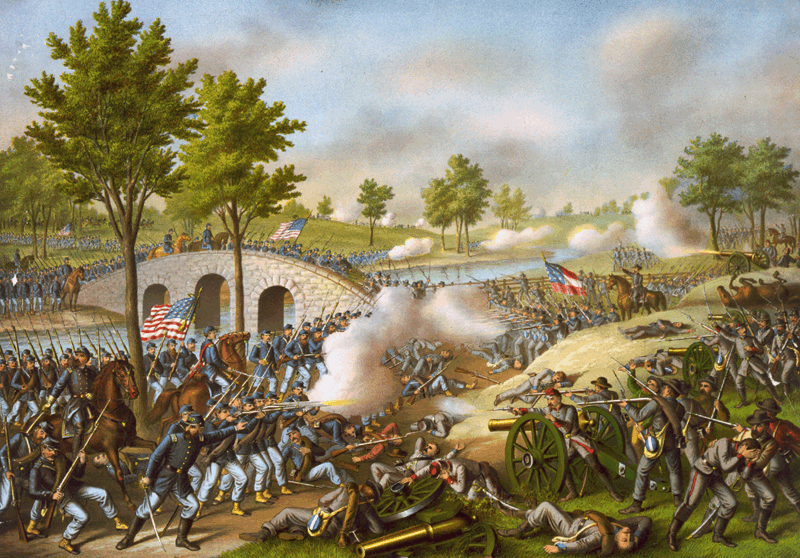

The Battle of Antietam:

Lee was surprised at McClellan’s sudden alacrity—as if he knew Lee’s route and dispositions, which of course he did. McClellan was bringing 75,000 men to the attack. Lee’s full strength was only 38,000 men, and he could bring that number to the field only if Jackson’s corps returned in time from recapturing Harpers Ferry. Lee dispatched 15,000 men to impede McClellan’s advance through a gap in Maryland’s Catoctin Mountains. He brought the rest of his army to the Maryland town of Sharpsburg on Antietam Creek, where he intended to meet McClellan’s thrust.

The battle was engaged on 17 September 1862. The odds against Lee narrowed with the clock. Each advancing hour brought more Confederates from the march to the battle line. In the morning, as Lee arranged his men at Sharpsburg, he brought barely a quarter as many troops as McClellan to the field. By afternoon, with the arrival of Jackson, he had shaved the odds to three to one against him. And at full strength, which he did not have until the battle was nearly over, he was still outnumbered by two to one.

The battle was desperate. In the first four hours of combat, 13,000 men in blue and grey fell as casualties in the bloodiest day of the war.

Twice, the Confederate line was almost overwhelmed: first at Bloody Lane, where the Confederates, mistakenly thinking they had been ordered to retreat, nearly allowed their forces to be divided; and then late in the day when Lee’s right flank, which he had continually stripped to support his left, began to give way under a fierce, sustained attack by Union General Ambrose Burnside. As the flank finally dissolved under Federal fire, Burnside had a clear field to destroy Lee’s army.

But then, bang on time, after a seventeen-mile forced march, came Confederate General A. P. Hill’s men from Harpers Ferry. Hill brought only 3,000 men to field—2,000 others had either fallen out or been left straggling behind—but with serendipitous precision, they arrived exactly when and where the Confederates needed him most, on Burnside’s flank. Despite the rigors of the march, Hill’s men tore into the Federals, scattering the Union assault. The day of battle was over.

That night, Lee ordered no retreat. His men made camp, rested, and held their ground—daring the Federals to attack them again the next day. McClellan declined the opportunity. So, with nightfall, Lee pulled the men out of their lines and led them back across the Potomac to the safety of Virginia, with A. P. Hill smacking a contingent of pursuing Federals into the north bank of the Potomac, providing, in the words of historian Shelby Foote, “a sort of upbeat coda, after the crash and thunder of what had gone on before.”

What You Need to Know:

The Battle of Sharpsburg is often considered a Confederate defeat, because it ended Lee’s invasion and thwarted his plans. So it did, but Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia deserve credit for what was also a brilliant tactical victory in the battle itself. The Confederates had held their ground against overwhelming odds, and held it again without challenge the next day. And if Lee could not take his army farther north, J. E. B. Stuart took his cavalry as far north as Chambersburg, Pennsylvania. President Lincoln was certainly not well pleased. He relieved General McClellan from command.

The Battle of Antietam—an 1862 clash between Robert E. lee’s Army of Northern Virginian and George McClellan’s Army of the Potomac—was the deadliest one-day battle in American history, with a total of 22,717 dead, wounded or missing. It came after Lee thwarted McClellan’s plans to lay siege to the Confederate capitol of Richmond and tried to seize the momentum by crossing north into Maryland.

Background

- John Pope and the Army of Virginia

-

-

- Lincoln ordered General John Pope, who had captured Island Ten on the Mississippi, East.

- Lincoln put all the soldiers who had been under Fremont, Banks, and McDowell under Pope’s command, and gave them the name the Army of Virginia.

- Pope moved his army to Gordonsville in central VA. There he would be able to menace key railroads in VA. He would also threaten Lee’s western flank.

- Pope was an arrogant man. As soon as he arrived, he issued a statement in which he said “I have come to you from the West, where we have always seen the backs of our enemies; from an army whose business it has been to seek the adversary and to beat him when he was found; whose policy has been attack and not defense.”

- Pope also bragged that he had his headquarters in the saddle. Some replied that he had his headquarters where his hindquarters ought to be.

- Unlike McClellan, Pope was a Republican and promised to be tougher on the rebels.

- Lee, normally very polite, wrote “This miscreant Pope must be suppressed.”

-

- Lee’s Activity

-

-

- General Lee divided his army into two corps, one under Jackson and one under Longstreet.

- Lee sent Jackson and his corps to deal with Pope’s threat. Lee and Longstreet stayed behind to watch McClellan, who was still at Harrison’s Landing.

- On August 9, Jackson ran into Pope’s advanced guard and defeated them at Cedar Mountain. The Federals pulled back.

- Lee realized that McClellan and the Army of the Potomac were being recalled to Washington. Lee and Longstreet marched north to unite with Jackson.

- Lee re-divided his army, sending Jackson around Pope’s right flank. Jackson reached Pope’s rear and captured an enormous supply depot at Manassas Junction.

-

- Second Bull Run (August 28-30)

-

- On August 29, Pope turned around and attacked Jackson.

- McClellan refused to send two corps to aid Pope. During the battle, McDowell handled his corps ineptly, and another corps commander, Fitz John Porter, disobeyed Pope’s order to attack (for which he was later court martialed and kicked out of the army).

- As Pope’s army was fighting Jackson, Longstreet attacked his left flank and drove many Federals from the field.

- Pope retreated (orderly this time) to Washington.

- The Confederates had 9000 casualties, while the Federals had 16,000.

- Lincoln removed Pope from command and sent him to Minnesota to deal with the Sioux. Lincoln then put McClellan in command of all of the troops in Washington (his and Pope’s). He said “we must use the tools we have.”

Battle of Antietam

- The Plan of Battle of Antietam

-

- Lee wanted to keep the initiative.

- Northern Virginia had been ravaged. There were almost no supplies left. Lee wanted to take the army somewhere new that had fresh supplies.

- Lee wanted to go north and west of Washington and lure the Federals out of Washington.

- He also thought that Marylanders would flock to his ranks.

- Movement

-

-

- On September 4, the Army of the Northern Virginia crossed the Potomac at a point west of Washington. His target was the Federal rail center at Harrisburg, PA.

- As Lee’s army marched, they sang “Maryland, My Maryland.” It didn’t work. Few Marylanders joined Lee’s army.

- They marched to Frederick, MD. There Lee decided to divide his army again. About half of them, under Jackson, would attack Harper’s Ferry, while the rest would stay in MD.

- During the campaign, between one third and one half of Lee’s army fell out of the ranks. Some did not want to fight outside of the South, while others were hungry and/or exhausted.

- On September 13, two Federal soldiers found a copy of Lee’s orders wrapped around a bundle of cigars. These were sent to McClellan. McClellan said, “Here is a paper with which, if I cannot whip Bobby Lee, I will be willing to go home.”

- McClellan went after Lee, more quickly than usual (but still not quickly). — here

- A small number of Federal and Confederate soldiers clashed on the 14th.

- Harper’s Ferry fell to Jackson on the 15th (with 12,000 prisoners). Lee ordered Jackson to march to Sharpsburg and meet him there.

- The rest of the Confederate army (30,000-35,000 men) took up positions on the crest of a ridge near the town. The Potomac was at their back, and there was only one place where they could cross it. In their front ran a creek called Antietam.

- The Battle of Antietamon the Confederate Left

- McClellan had 70,000 men. His plan was to apply pressure to both Confederate flanks, weaken the center and then punch through it, cutting Lee off from the Potomac.

- McClellan failed to attack all parts of the rebel line simultaneously. The battle was really three separate battles, beginning with one on the Union right, then the center, then the Union left. This enabled Lee to freely lift troops from one part of his line to another.

- On the left, the Union Corps under Joseph Hooker attacked Jackson’s corps who were hidden behind a cornfield. The bluecoats’ objective was a plateau on which there was a small, white church owned by a sect called the Dunkards. (Brief bio on Hooker).

- The fighting went back and forth across the cornfield. Many men experienced a brief spell of “battle madness”, attacking maniacally while laughing.

- Hooker’s men were closing in on the church, when a division under Confederate General John B. Hood pushed the Federals back. Hooker is shot and has to leave the field.

- One Union officer reported that “every stalk of corn in the greater part of the field was cut as closely as with a knife, and the slain lay in rows precisely as they had stood in their ranks a few minutes before.” There were more than 8000 casualties in the cornfield alone. One regiment, the First Texas, suffered 80% casualties there.

- Jackson, looking out over the carnage, said “God has been very good to us this day.”

- The Battle in the Confederate Center

- The rebels dug in in a sunken road that served as a trench. Lee ordered that the position be held at all cost.

- The Federals attacked. When they were just a few yards away, the Confederate commander John B. Gordon, ordered his troops to fire.

- The bluecoats retreated and came back five times. Their commander was killed, and Gordon was shot five times.

- The sunken road filled with Confederate bodies and was later given the name “The Bloody Lane.”

- The Confederate line was just about to break, but McClellan ordered the attack to stop. He tells a subordinate that to send in reserves “wouldn’t be prudent.”

- The Battle on the Confederate Right

- A Union corps under Ambrose Burnside fought to cross a well-guarded stone bridge that crossed the creek. (The bridge is later named after Burnside.)

- Burnside had about 12,000 men against only 400 rebels, but the rebels had 12 cannon commanded a bluff that overlooked the bridge. They poured down withering fire into the Federals.

- It took three hours for the Federals to get across the bridge. Burnside’s soldiers pushed the Confederates back toward the road that led to the ford across the Potomac.

- It looks like disaster is looming for the Confederates, but at the last minute, the last Confederate division (under AP Hill) arrived from Harper’s Ferry to protect the road and stop the Union advance. Hill’s arrival (after a forced march) saves Lee’s army.

- Burnside asked McClellan for reinforcements, but McClellan refused to send any.

-

- Outcome of Battle of Antietam

-

-

- McClellan did not use 25% of his army.

- The federals pushed the Confederates almost back

- This was the bloodiest single day in American history. 10,500 Confederates were casualties (this was 1/3 of Lee’s army), with about 1600 killed. 12,500 Federals fell (2100 killed). This is twice the number of casualties at D-Day.

- At “Bloody Lane”, one officer claimed to have walked 100 yards over bodies without touching the ground.

- Lee remained on the field on the 18th. The two sides exchanged wounded.

- Lee returned to Virginia on the 19th. McClellan only sent a few troops to harass the Confederates but did not pursue in force. Lee’s army got away.

- Scott mentions that McClellan’s blunders in this campaign enabled the Confederacy to maintain an Eastern army and continue the war for more than two years

-

- Consequences of Battle of Antietam

-

- The battle was a tactical draw, but the Union held the field.

- Lincoln visited the battlefield and tried get McClellan to pursue Lee. McClellan refused.

- In November, Lincoln removed McClellan. McClellan wrote “They have made a great mistake. Alas for my country!”

- The British, who had been thinking of trying to mediate, decided not to.

- This was enough of a Union victory for Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation. (More on this next time).

- Many modern scholars, for this reason, call it the “Turning Point of the War.”

Would you like to learn the complete history of the Civil War? Click here for our podcast series Key Battles of the Civil War

Would you like to learn the complete history of the Civil War? Click here for our podcast series Key Battles of the Civil War

Cite This Article

"The Battle of Antietam (September 17, 1862)" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

April 24, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/battle-of-antietam-17-september-1862>

More Citation Information.