The following article on the Battle of Leyte Gulf is an excerpt from Barrett Tillman’s book On Wave and Wing: The 100 Year Quest to Perfect the Aircraft Carrier. It is available to order now at Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

The pace of the Pacific War accelerated after the Mariana and Palau Islands campaign, with the fast carriers at the tip of the spear. In a controversial move, the joint chiefs ordered the Marines to seize Peleliu in the Palau Islands to guard the eastern flank of the upcoming return to the Philippines. The First Division went ashore in mid-September, expecting to wrap up the craggy island in a matter of days. Instead, the operation lasted two and a half months, with critics arguing that it turned into an unnecessary, sanguinary meat grinder. Fast carriers supported the landings but had more urgent business six hundred miles westward in late October.

Army General Douglas MacArthur’s 1942 pledge to return to the Philippines prompted high-level discussion regarding the advisability of seizing the Philippines or Formosa. For a variety of reasons— including a national debt to the long-suffering Filipino people—a huge amphibious force set its sights on Leyte Gulf that fall. The stage was being set for the Battle of Leyte Gulf.

The engagement, fought in waters near the Phillipoine islands of Leyte, Luzon, and Samar, took place from October 23-26. The beliigerents were American and Australian forces against the Imperial Japanese Navy. Historians consider the battle to be the largest naval battle of World War Two and perhaps the largest naval battle in history. Four separate engagements took place: The Battle of the Sibuyan Sea, the Battle of Surigao Strait, the BAttle of Cape Engano and the Battle of Samar. Because Japan had fewer aircraft than the Allies had sea vessels, it was the first battle in which Japanese pilots carried out organized kamikaze attacks.

Third Fleet sought to weaken Japan at the periphery before striking the Philippines. Therefore, carriers hit Okinawa on October 10 and Formosa on October 12. Carrier aircrews estimated they destroyed 650 planes at Formosa, while Japan admitted half as many—still a heavy blow. Yet Tokyo, still slurping its homemade brew, gleefully announced sinking three dozen American ships, including battleships and carriers. Even the normally level-headed Kamikaze master, Vice Admiral Matome Ugaki, thought his airmen had destroyed three carriers and three other ships. In truth, two U.S. cruisers were badly damaged but survived.

“Bull” Halsey’s Third Fleet arrived off the Philippines with Task Force Thirty-Eight’s four groups deploying sixteen fast carriers. From bases in Japan and the East Indies the Imperial Navy launched a three-pronged response with carriers, battleships, and scores of escorts. The sprawling, four-day slugfest began on October 24.

Halsey had released two groups to head eastward for replenishment when the crisis broke. He recalled Rear Admiral Gerald Bogan’s Task Group 38.4, while allowing Vice Admiral John McCain’s 38.1 to proceed to Ulithi, taking five flight decks out of action until late in the battle. Thankfully, Marc Mitscher’s fast carriers were not the only flattops involved. Vice Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid, who had commanded at Santa Cruz, led Seventh Fleet including eighteen CVEs for close air support and antisubmarine patrol.

In the Sibuyan Sea—another front of the Battle of Leyte Gulf located on the western side of the Philippines—carrier airpower destroyed one of the largest battleships afloat. Three fast carrier groups launched multiple strikes against Vice Admiral Takeo Kurita’s five battleships, twelve cruisers, and fifteen destroyers. Some 260 blue aircraft swarmed the sixty-four thousand-ton Musashi for more than five hours, hammering her with seventeen bombs and nineteen torpedoes, heavily represented by Enterprise and Franklin’s air groups. Ten aircraft fell to Japanese AA, but it was the first time carrier planes sank a battleship underway, unassisted by surface combatants. It would not be the last.

Kurita had already lost two cruisers to submarines and another turned back with bomb damage, but after regrouping he continued his mission to enter Leyte Gulf, unknown to Halsey.

Meanwhile, Japanese land-based aircraft posed a serious threat to the fast carriers. Winging seaward in three large formations, they were intercepted by relays of F6Fs well managed by fighter-direction officers. But fighters were spread thin. In Task Group 38.3 Essex’s last two available Hellcats were launched with hostiles inbound, putting Commander David McCampbell and Lieutenant (jg) Roy Rushing onto a gaggle of Zekes. In the next ninety minutes McCampbell claimed nine kills—the all-time U.S. one-day record—and Rushing six. In all, Essex’s Fighting Fifteen was credited with forty-three kills that day.

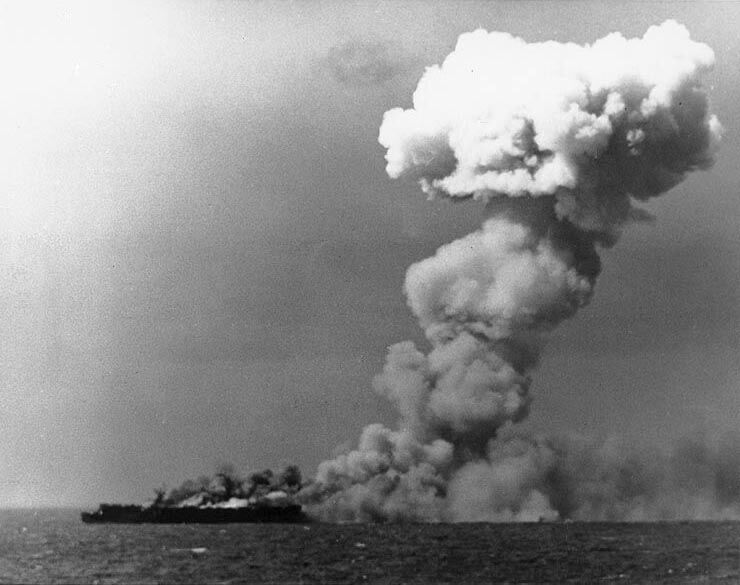

In the same group Princeton’s shark-mouthed VF-27 fought hard for its ship, splashing thirty-six raiders. But a single Yokosuka Judy put a 550-pound bomb through “Sweet P’s” flight deck, igniting ordnance on the hangar deck. The light cruiser Birmingham (CL-62) came alongside to take off survivors when a huge secondary explosion swept the would-be rescuer, inflicting nearly seven hundred casualties. Princeton was scuttled after an eight-hour ordeal, losing 108 men. She was the first American fast carrier sunk since Santa Cruz and remained the last. Carrier aviators claimed 270 kills on October 24, the second highest count of the war.

But the Imperial Navy was not ready to give up the Battle of Leyte Gulf.

Under cover of darkness October 24–25, Kurita transited San Bernardino Strait between Luzon and Samar, eastbound, intending to fall upon MacArthur’s vulnerable transports in the gulf. The Navy’s first full-time night flying unit, Air Group 41 in light carrier Independence, had Avengers airborne that night, tracking the large enemy force. Mitscher assumed that Third Fleet had the information, but for reasons still unclear, Halsey ignored it.

Additionally, that afternoon Task Force Thirty-Eight search teams had found Ozawa’s four carriers off Luzon’s northeast coast. That information, later combined with Independence’s report of Kurita’s eastward course, bothered some senior officers, who correctly deduced Ozawa’s purpose: to draw the fast carriers north, clearing the way for Kurita’s center force. Mitscher, informed of the developing situation, declined to intervene with Halsey.

Well to the south, the third prong of Tokyo’s offensive met Seventh Fleet units in Surigao Strait separating Leyte and Mindanao—everything from PT boats to battleships. In the world’s last major surface engagement, the annihilation was nearly complete, leaving the dogged Kurita pressing eastward while Jisabuo Ozawa—survivor of the Marianas—lurked well to the north with four partly equipped carriers.

THE BATTLE OF LEYTE GULF: DAY TWO

Shortly past dawn on October 25, Vice Admiral Kinkaid’s three escort carrier groups had patrols airborne. An Avenger sighted large ships with pagoda masts emerging from San Bernardino strait and radioed the alarming news.

All that stood in Kurita’s path was Rear Admiral Clifton Sprague’s Task Group 77.4.3, with six CVEs and seven escorts, off Samar’s east coast. “Taffy Three” turned away, making smoke, launching aircraft, and hollering for help. Sprague faced four battleships, eight cruisers, and eleven destroyers. But support from Taffy Two added more Avengers and Wildcats to Sprague’s numbers.

As the “smallboys” attacked with torpedoes and five-inch gunfire, aviators made repeated runs with bombs, torpedoes, and strafing passes. One Wildcat pilot made twenty-six runs, most of them without ammunition.

Unable to outrun the enemy, the 19-knot CVEs were chased down. Gambier Bay (CVE-73) succumbed to cruiser guns, as did three of the escorts. After HMS Glorious in 1940, she was only the second aircraft carrier sunk by surface ships. But Kurita, impressed with the ferocity of the “jeep” carriers’ response, and mindful of the pummeling he had taken the day before, called off the chase. Just as an historic victory lay on the horizon, he disengaged. Kinkaid’s transports—and MacArthur’s source of supply—were safe.

Still, Taffy Three remained in peril. That afternoon St. Lo (CVE-63), originally named Midway, was attacked by a single Zero that made no effort to pull out of its dive. Wracked by fire, the little flattop went down, first victim of the Special Attack Corps: the Kamikaze had arrived. Six more CVEs were tagged that day.

While the drama played out near Samar, the Japanese waved an irresistible target under Halsey’s nose. Ozawa’s four carriers steamed off the northeast Philippines, seemingly representing the third major threat after the surface forces in San Bernardino and Surigao straits. Once ComThirdFleet got the news, Halsey reacted predictably: he rushed to destroy Tokyo’s remaining flattops. In his haste, he committed a severe blunder, leaving San Bernardino unguarded. He assumed that battleships of Vice Admiral Willis Lee’s powerful Task Force Thirty-Four would prevent an enemy force from entering the gulf. He did not realize as he pounded north that all seven battleships and their screens in Lee’s contingency force remained integrated into the fast carrier task groups.

Bull Halsey was more a fighter than a thinker. An instinctive warrior, he rode to where he imagined the guns were sounding. Only when the stunning news arrived of Japanese battleships pounding Taffy Three did he realize that he had been snookered. Worse, he wasted an hour or more ranting and sulking before deciding on a course of action.

Ozawa lay more than four hundred miles from the Taffies, and Halsey was in between. The Bull finally ordered Lee’s battlewagons— racing ahead of the carriers—to reverse helm and move southward, although everyone knew it was far too late.

The four carriers in Ozawa’s Mobile Fleet had deployed with just 116 aircraft, but by the morning of October 25 they retained only twenty-nine. The ensuing clash could only go one way.

Starting at 8:00 a.m. Mitscher launched 180 aircraft, the first of six strikes totaling more than five hundred sorties. The on-scene coordinators were air group commanders from TG-38.3: first from Essex, then from Lexington. The F6Fs brushed aside the dozen or so Zeros trying to defend their flight decks as “99 Rebel” and “99 Mohawk” assigned targets. Lexington and Langley’s aircrews wrote the final log entry for Zuikaku, survivor of Coral Sea, Eastern Solomons, and Santa Cruz. Other air groups sank CVLs Chitose and Zuiho as well as a destroyer.

Ozawa shifted his flag to cruiser Oyodo.

SINKING OZAWA AT THE BATTLE OF LEYTE GULF

That morning Essex’s air group commander David McCampbell directed strikes that sank the light carrier Chitose. Relieving him as target coordinator was Lexington’s Commander Hugh Winters, controlling some two hundred aircraft. He recalled, “There was no chance for surprise, as the Japs were already bleeding some, so we didn’t have to shoot on sight, so to speak. We wanted all the carriers, with maybe a BB or CA for the cherry on top.”

Winters directed his squadrons against Zuikaku, Zuiho, and the larger escorts. He noted:

The heavy haze of AA smoke trailing off the quarter gave good windage for our dive bombers as we pushed over. . . . The ships were using new anti-aircraft stuff with wires and burning phosphorous shells which put up all different-colored fire and smoke around our planes. But we had faced so much deadly AA for so many lousy targets that it didn’t bother us too much, hunting this big game. The boys were as cool as any professionals working in a hospital or law office.

The Zuiho limped on, burning, but the Zuikaku stopped and started to die on one side. She needed no more, but hung in there for awhile, and her AA battery was nasty. In the excitement, I stayed down too low (not very professional), and got some holes in my left wing. I knew it would be a long afternoon, so I throttled back to almost stalling speed and leaned out the fuel to practically a back-firing mixture.

Winters assigned subsequent air groups according to his target priority, and watched Zuiho sink, then Zuikaku capsize. “No big explosions, no steam from flooded firerooms, no fire and smoke—just a few huge bubbles. Quietly, and it seemed to me, with dignity.”

Thus perished the last survivor of the Pearl Harbor attackers. The light carrier Chiyoda lingered a bit longer. Hugh Winters and wingman Ensign Barney Garbow had witnessed something unprecedented—they saw three aircraft carriers sink during one mission.

Halsey dispatched four cruisers and nine destroyers as a pickup team to complete the execution. They sank Chiyoda late that afternoon and pummeled a remaining destroyer. Carrier planes continued scouring Philippine waters during October 26 and 27, picking off a light cruiser and four more destroyers. It brought Japanese losses in the four-day battle to twenty-six combatants, totaling three hundred thousand tons.

The Battle of Leyte Gulf officially entered the books as the Second Battle of the Philippine Sea, though most of the action occurred nearly one thousand miles from the June turkey shoot. Whatever the battle’s official name, after October 1944 the Imperial Navy was finished.

Despite an unprecedented level of destruction inflicted upon the Japanese Navy, the Battle of Leyte Gulf left a sour taste in many American mouths. Halsey’s bungled arrangement for covering San Bernardino Strait resulted in the unnecessary loss of four Taffy Three ships and nearly six hundred lives. (St. Lo and Princeton could not be laid to Halsey’s account.) The fault was shared, however, with MacArthur’s unnecessarily complex communications structure and Kinkaid’s acquiescence to it. Halsey stayed, and as events would show, he remained beyond all accountability.

Historians still debate whether the Battle of Leyte Gulf represented the sixth flattop battle. Purists insist that it did not, because the carrier versus carrier phase was totally one-sided. By the time Halsey’s air groups got at Ozawa on October 25, the four Japanese carriers were nearly empty. Even upon deployment, many Imperial Navy pilots could only launch from their flight decks, being untrained in shipboard landings. In any case, Leyte was the last time that carrier-based aircraft—or any others—sank opposing carriers at sea.

From the period after the Battle of Leyte Gulf through December, eight more carriers were hit by Kamikazes. The attackers sent Intrepid, Franklin, and Belleau Wood stateside for repairs that would take between two and four months. It was becoming increasingly obvious: the only way to defeat the Kamikaze was to kill him, as he could not be deterred.

Toward that end, the Navy asked for help from the Marines. With a shortage of carrier fighters to combat Kamikazes, the Pacific Fleet began training leatherneck Corsair squadrons in carrier operations. The first two squadrons, VMF-124 and 213, were experienced Solomons units that reported aboard Essex at Ulithi in December. They had a rough initiation to Western Pacific weather, suffering heavy losses, but they paid their way. Eight more Marine squadrons joined them in the new year.

Meanwhile, nature reminded the U.S. Navy that Imperial Japan could be the lesser enemy. While refueling in mid-December, Halsey wanted to remain in position to support MacArthur’s forces on Luzon, but a major tropic storm called Typhoon Cobra spun up in the Philippine Sea, tracking north-northwest. Ignoring warnings from meteorologists—complicated by some inaccurate forecasts—Halsey continued refueling. Consequently, he took Third Fleet into the mouth of the storm, prompting comparisons to the original Divine Wind that saved Japan from Mongol invasions in the thirteenth century. The result was a disaster. Battling one hundred mph winds, three destroyers capsized and nearly eight hundred men drowned.

Light and escort carriers were especially vulnerable, rolling eighteen to twenty degrees, whipped by violent winds. Avengers and Hellcats snapped their flight deck tie-downs and tumbled into catwalks or careened overboard. One loose fighter or bomber could cause havoc, colliding with other planes, smashing into fuel lines, and starting blazing fires.

Five fast carriers and four CVEs suffered damage, with Monterey (CVL-26) forced to Bremerton, Washington, for repairs after a serious fire on the hangar deck. Nine other ships incurred major damage; six suffered lesser damage. More than one hundred aircraft were destroyed or badly damaged at no expense to the enemy.

Summarizing the damage of the Battle of Leyte Gulf, Nimitz reflected that Typhoon Cobra “represented a more crippling blow to the Third Fleet than it might be expected to suffer in anything less than a major action.”

Halsey might have been relieved of command after the storm, coming so soon after the Battle of Leyte Gulf fiasco. But perceived needs of the service prevailed: a board of inquiry faulted him for poor judgment while declining to recommend sanction. Many officers and sailors grumbled about politics uber alles.

However, there had been more action at the expense of Japan. The last carrier sunk in 1944 was Shinano, third of the Yamato-class battleships, converted to a carrier, and slated for sea trials in November. On the night of October 29, en route to Kure, she fell afoul of USS Archerfish (SS-311), which put four torpedoes into her starboard side, sinking the seventy-one thousand-ton behemoth in about six hours.

This article on the Battle of Leyte Gulf is an excerpt from Barrett Tillman’s book On Wave and Wing: The 100 Year Quest to Perfect the Aircraft Carrier. It is available to order now at Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

You can also buy the book by clicking on the buttons to the left.

This article is part of our larger resource on the WW2 Navies warfare. Click here for our comprehensive article on the WW2 Navies.

Cite This Article

"The Battle of Leyte Gulf: WW2’s Largest Naval Battle" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

April 20, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/battle-of-leyte-gulf>

More Citation Information.