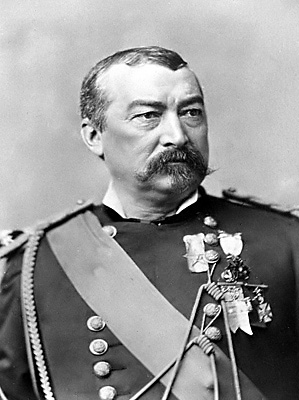

In physique Philip Sheridan was shaped like the Fighting Irish leprechaun of Notre Dame. He was only five feet five inches tall, mostly body with scant legs, long arms attached to ready fists, and slit eyes that burned defiance. Abraham Lincoln described Sheridan as “a brown, chunky little chap, with a long body, short legs, not enough neck to hang him, and such long arms that if his ankles itch he can scratch them without stooping.”

Sheridan was never put off by the size of an opponent. During the war, he once took a dislike to the “saucy and impertinent manner” of a brawny, six-foot-tall train conductor. He handled things the Sheridan way. He thrashed him with his fists, threw him off the train, and then returned to his conversation with General George Thomas.

Philip Sheridan was the son of an Irish immigrant, a road laborer, and he never harkened after anything softer than a soldier’s life. It was soldiering that determined nearly everything about him: his loyalties and prejudices, his sense of duty and honor, his ideas of justice and order. He was a soldier’s soldier of a certain type: demanding, hard-swearing, but also one who burned the midnight oil to make sure his troops were adequately provisioned (he had been trained as a quartermaster) and with battle plans adequately laid. No officer was more diligent in gathering intelligence about topography and troop movements. And he was tough. Grant liked him for the same reason Lincoln liked Grant: because he was willing to fight. Like Bedford Forrest, he knew that war means fighting and fighting means killing; he once told a Federal officer, “Go in, sir, and get some of your men killed.” It wouldn’t do to hang about when it was battles and fighting that won wars.

He grew up in the small town of Somerset, Ohio, took the usual smattering of small town education enlivened by small town boyish truancies and became a store clerk and bookkeeper—but one with ambitions to win a congressional appointment to the United States Military Academy. He succeeded when Congressman Thomas Ritchey’s previous candidate flunked out. It was a pretty turn of events for a store clerk who had only happened to make the acquaintance of the congressman as a customer. As Lana Turner was discovered at Schwab’s Drug Store, so Philip Sheridan was discovered behind the counter of Finck & Dittoes. It can be argued who had the finer career.

He crammed for the entrance exam, and kept cramming to keep up his grades, and found it impossible to refrain from fighting with his fellow cadets, (which resulted in a year-long expulsion). Nevertheless he graduated, albeit a year behind, and with a nice record in demerits, and was posted where such young men were sent—as an infantry officer on the Texas frontier, where he hunted, socialized with Mexican families (developing sympathies that would be important later), and had occasional scrapes with Indians. He followed up this useful experience with similar scrapes with Indians in the Pacific Northwest, one of whom sent a bullet brushing across his nose, exploding into the neck of the orderly beside him. But he also acted as a sort of colonial administrator to the tribes that fell in his purview—not only punishing them when they applied war paint, but attempting to rid them of superstitions and to enforce the white man’s law (against murder, among other things). The justice might have been of a frontier variety, but though short and Irish, Philip Sheridan had most assuredly taken up the white man’s burden, as well as an Indian mistress.

Philip Sheridan, the Quartermaster and Fighting General

When the Union divided, Sheridan won swift promotion. His first major task took him not to blood-drenched battlefields, but to the disorderly red-ink accounts of General John C. Frémont’s quartermaster. Frémont’s chaotic administration of Missouri—full of pomp and abolitionist circumstance, but rather lacking in practical aptitude, except for the graft of his quartermaster—led to the quartermaster’s court-martial. Philip Sheridan was drafted by General Henry Halleck to help make sense of the financial misdeeds and audit the accounts. Using the keen eye of a professional clerk and bookkeeper, he executed his duties with dispatch.

It’s likely that few people who think of Sheridan think of him wearing green eye-shades, but it was a fitting way for him to enter the war. For him, there were no great political issues involved. He cared neither for abolitionism or states’ rights or any of the other arguments roiling the political waters of the Republic. He was an Irish immigrant’s son. America had been good to him, the army had been good to him, he followed his orders, and just as books had to balanced, rebels had to be punished, and there was no need for any gasconading—or sentimentality—about it. He did say to a group of friends, family, and well-wishers, “This country is too great and good to be destroyed.” But that was about the extent of his politics.

Henry Halleck was enamored of Philip Sheridan’s wizardry with accounts, and soon posted him a commissary officer. Sheridan, however, convinced Halleck that he should also be chief quartermaster for the Army of Southwest Missouri, and so it was done. Sheridan took the same practicality that he had employed analyzing accounts to the more vigorous task of expropriating the property of Southern-sympathizing civilians for the use of the army. He would not, however, unlike Frémont’s quartermaster, condone thievery that cost the U.S. Treasury. Sheridan condemned soldiers who stole farmer’s horses, then sold them to the army, as simple thieves who would not be tolerated, even as he was pressured to tolerate them by a superior officer.

Philip Sheridan was an excellent quartermaster, but as an experienced Indian-fighter he was itching to get his licks in against the Johnny Rebs. He got his chance. In May 1862, he was commissioned a colonel of the Michigan cavalry, and only days later was involved in the first major raid by Union cavalry, ripping up railroad ties in Mississippi and bending them into the sort of bowties that Sherman and Sheridan considered their contribution to dressing up the Southern countryside. As Sheridan had impressed Halleck in accounting, so did Sheridan impress the likes of General William Rosecrans who saw in Sheridan an aggressive officer who was an excellent scout, with a sound analysis of topography and intelligence, and most of all a desire and a talent for fighting.

One of Philip Sheridan’s tutors in command was General Gordon Granger. Confronted by Confederate guerillas, Granger once expostulated: “We must push every man, woman, and child before us or put every man to death found in our lines. We have in fact soon to come to a war of subjugation, and the sooner the better.” Sheridan had no qualms fighting such a war. By September 1862, he was promoted brigadier general.

A month later, Philip Sheridan fought in the biggest and bloodiest battle ever fought on Kentuckian soil, the Battle of Perryville. The Confederates under the ever-lamentable leadership of Braxton Bragg, suffered more than 3,000 casualties, the Federals more than 4,000. The stakes were high. In Lincoln’s famous words: “I hope to have God on my side, but I must have Kentucky. I think to lose Kentucky is nearly the same as losing the whole game.” Luckily for the Union, Braxton Bragg was master at losing entire games. In this case, he won a tactical victory on the battlefield, which he turned into a strategic defeat by vacating Kentucky to the Union. Sheridan acquitted himself well, though he was not involved in the major part of the action. Blessed with the high ground and a manpower advantage of four to one, he thrashed the grey coats before him. But at the end of the battle both armies felt they had lost, because neither pursued their gains.

Philip Sheridan closed 1862, with another battlefield triumph at Murfreesboro, Tennessee, where his troops thwarted the initial Confederate advance, and then under extreme pressure (his men ran out of ammunition and suffered 40 percent casualties) performed a gritty fighting withdrawal. A brigadier general said of Sheridan’s conduct that “I knew it was hell when I saw Phil Sheridan, with hat in one hand and sword in the other, fighting as if he were the devil incarnate.” A devil, perhaps, but a calm one too, as he lit and puffed on a cheroot during the fight. When he emerged from the battle, he told General Rosecrans, “Here we are, all that are left of us.” General Grant credited Sheridan’s tenacity with saving Rosecrans’s army and making possible the Union victory. Sheridan’s service was recognized the following spring, when he was elevated to major general at the age of thirty-two.

He fought at Chickamauga and Chattanooga: in the former, having to extricate his men in another fighting withdrawal (but unlike Rosecrans he didn’t flee from the field) and in the latter he was one of the leaders of the massive blue surge up Missionary Ridge. Resting under the sight of the enemy, he lifted a flask to the Confederates above, saying “Here’s to you!” The response was an explosion that splashed his face with dirt. “That is ungenerous,” he shouted “I shall take those guns for that!” And he did—and led the Yankee pursuit of the fleeing Southerners.

Grant’s Man on Horseback

Grant, who had watched Philip Sheridan’s charge up Missionary Ridge, knew “Little Phil” to be another fighter who wanted always to press the enemy. He was the sort of man Grant wanted as he took over operations against Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia. When someone pointed out how short he was, Grant replied, “You’ll find him big enough for the purpose before we get through with him.” Likewise, when General George Meade told Grant of Sheridan’s boast that he could “thrash hell out of Stuart any day,” Grant responded, “Did Sheridan say that? Well, he generally knows what he’s talking about. Let him start right out and do it.”

Philip Sheridan performed poorly for the irascible General George Meade. Scouting and screening for the Army of the Potomac were not duties fit for Sheridan’s talents, or so he thought. What he wanted to do was raid the enemy, and Grant supported him, giving him an independent command that allowed him to chase down Jeb Stuart, bring him to battle, and kill him—which gave Sheridan an ungallant pleasure. There was much about Sheridan’s way of war—the Union way of war—that was ungallant. Most famous, in this category, was Sheridan’s destruction of the farms of the Shenandoah Valley, an act of rapine that Virginians knew as “the burning.”

Sheridan took the view that the prospect of Southern independence was so outrageous that not only must the South be subjugated by war, but Southern civilians must be punished for desiring a country of their own and for defending their homes from invading armies. This attitude would, incidentally, make him a top notch enforcer of martial law during Reconstruction, during which time he sided with the Radical Republicans.

Grant’s famous order that he wanted the Shenandoah Valley made a “desert,” that all its livestock and food should be confiscated or destroyed, that all its people should be displaced, “so that crows flying over it for the balance of the season will have to carry their provender with them” was in perfect accord with Sheridan’s own views; and it fell to him to expand the Union program of devastation of the Valley that had already begun. Grant told him, “If the war is to last another year, we want the Shenandoah Valley to remain a barren waste.”

There were real battles along the way (like the battle for Winchester on 18 September 1864, which claimed the life of Confederate Colonel George S. Patton, grandfather of the World War II general), but the campaign quickly took on an ugly patina. Not content with waging war on civilians, Sheridan’s men treated, as a matter of policy, endorsed by General Grant, Confederate cavalryman John S. Mosby’s rangers not as soldiers but as “ruffians” and “murderers” who could be executed without trial—even as Philip Sheridan organized his own ranger force (which sometimes operated under the guise of captured Confederate uniforms, and was notorious for its thievery).

The one bit of legitimate glory for Sheridan was when he rallied his troops—shattered by a surprise attack launched by the Valley’s defender, Jubal Early—and turned what would have been a deeply embarrassing rout of the Federal forces at the Battle of Cedar Creek (19 October 1864) into an annihilation of Early as a threat to the Federal army. At one point a fleeing Yankee colonel yelled out to Sheridan, “The army is whipped,” only to be put down with the stinging reply, “You are, but the army isn’t,” as the general stormed past on his mount Rienzi. Philip Sheridan also showed courage and dash—though Lee’s army was broken at this point—when he led the Union charge that won the battle of Five Forks (1 April 1865), where he led Rienzi leaping over the Confederate defenses and in amongst the battered men in butternut and grey, who surrendered to the sharp little general.

But for a man who allegedly wanted to bring the war to an early conclusion—in the interests of “humanity”—Sheridan’s reaction to news that Lee was surrendering was distinctly odd, though distinctly in character: “Damn them, I wish they had held out an hour longer and I would have whipped hell out of them.” If denied that pleasure, he did join in with other Federal officers in ripping up the belongings of Wilmer McLean, in whose Appomattox home the surrender took place, to make off with souvenirs. Philip Sheridan bought the table where the surrender had been signed and then, as a beau geste, gave it to the boy general, and Sheridan favorite, George Armstrong Custer as a present for Custer’s wife.

Post-War Pugilist

Philip Sheridan ended the war as one of three burly musketeers—Sheridan, Sherman, and Grant—who had done more than any other generals to win the war for the Union, and had done so by waging war with a brutality that would make them notorious in the South for generations. To Sherman, Sheridan was “a persevering terrier dog.” To Grant, Sheridan had “no superior as a general, either living or dead, and perhaps not an equal.” They succeeded each other as the top general of the postwar United States Army—Grant, Sherman, and Sheridan—and to Sheridan (under Sherman’s watch) goes the credit for creating a postgraduate college for officers (at Fort Leavenworth).

Sheridan did not mellow after the war. Fully backed by Grant, he governed Texas and Louisiana as a martinet. He deposed governors and mayors and others as he saw fit, openly despised Southerners, Texans in particular, and sided with Republicans, freed blacks, and carpetbaggers in every dispute. Despite his later reputation as an Indian exterminator, Philip Sheridan also showed a marked preference for putting the political screws to Texans rather than protecting them from Indian raids, which he dismissed as a distraction. His real distraction, however, was Mexico where he and General Grant (the general who thought our Mexican war was immoral) were ready and eager to intervene on the side of the Juaristas in their war against the Frenchsupported government of the Austrian Archduke Maximilian. While American military adventurers plied both sides of the war, it is generally true that Southerners supported the Archduke (as cavaliers should) while Unionists supported the Mexican rabble. The Unionists won this war too, and Maximilian was eventually executed by a firing squad of ungrateful Mexicans.

Philip Sheridan ended his career as he began it, as an Indian fighter, though now he was a lieutenant general rather than a shavetail. His strategy was that of the Shenandoah: he reduced the Indians less by fighting them in open battle (such battles were fought, but the Indians’ hit and run tactics made them inconclusive) than by attacking the Indians in winter, when they did not expect paleface campaigns and were bedded down with their families and were vulnerable. In addition, he endorsed the free slaughter of the buffalo as a way to drive the Indians from the plains. A hunter himself, he was not entirely opposed to animals—he was instrumental, in fact, in creating Yellowstone National Park and ensuring that its wildlife was preserved—he just wanted to starve the Indians. Sheridan, who became rotund with age, well appreciated hunger as a military tool in driving one’s enemy to submit.

The Indians, of course, were not entirely innocent or undeserving of Sheridan’s wrath. There were Indian outrages aplenty—scalpings and mutilations and murders and rapes and raids (sometimes committed with rifles given to them by the government as peace offerings), that sickened Sheridan and fully justified in his own mind the harshest retribution, though that retribution was not always directed at the proper tribes or groups of savages. And Sheridan had lost friends to the Indians—most spectacularly, in the disaster at Little Big Horn in 1876, where his “brave boy” George Armstrong Custer met his fate.

Philip Sheridan’s ultimate fate was more pleasant. A bachelor for his first forty-four years, he broke his fast from the opposite sex by marrying a woman half his age, Irene Rucker, whose military family (her father was a colonel and assistant quartermaster of the army), had trained her well for life with Sheridan. This last great conquest brought him four children, three girls and a son who became a military aide to Theodore Roosevelt but died, only thirty-seven years old, of a heart attack—the same malady that claimed his father at the age of fifty-seven.

Would you like to learn the complete history of the Civil War? Click here for our podcast series Key Battles of the Civil War

Would you like to learn the complete history of the Civil War? Click here for our podcast series Key Battles of the Civil War

Cite This Article

"Union General Philip Sheridan (1831-1888)" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

April 19, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/civil-war-general-philip-sheridan>

More Citation Information.