COVID19, aka – the coronavirus, has triggered mass quarantines and spooked markets across the globe. To date, over 3,000 have died and over 100,000 infected. But however dangerous this virus ends up being, it doesn’t belong in the same galaxy as Spanish Flu, which killed up to 100 million in 1918, which was 5 percent of the earth’s population.

Today’s guest is Dr. Jeremy Brown, director of emergency care at the National Institute of Health and author of Influenza: The 100-Year Hunt to Cure the Deadliest Disease in History. He notes that great strides have been made in medicine the last century, and whatever happens next, it won’t be a second 1918.

We discuss the quarantine methods used in the ancient and medieval worlds during epidemics and pandemics; how the Spanish Flu pandemic began; what it was it like for an average person in 1918 and whether there was an omnipresent fear of death, or were people mostly resigned to their fate; how the Spanish flu pandemic ended; and finally, lessons from 1918 we should heed today.

Here’s the bottom line: with coronavirus, you will definitely have it much, much better than your great grandpappy did with Spanish flu.

Machine-Generated Transcript

Below is an AI-generated transcript complete with timecodes. This transcript may contain errors and is not a substitute for listening to the podcast episode.

Scott Rank 0:12

Hello everyone. Well, this is one of the most topical episodes we’ve ever done on this show because we’re doing something that is ripped from the headlines we’ll be talking about. Not exactly Coronavirus, but the type of infection that the coronavirus is and what are examples in history that looks similar to Coronavirus and what was something that was we all hope much worse. And all indications suggested a well, I’m very excited about this episode because I’m talking with perhaps one of the most qualified people who could be talking about this issue. And that is Dr. Jeremy Brown. Dr. Brown is an emergency physician, and he’s the author of the book, influenza, the hundred-year hunt to cure the deadliest disease in history. He’s the director of the Office of Emergency Care Research at the National Institute of Health, but he’s on the show in a personal capacity. And I want to stress that because if he makes predictions, then it’s not a pronouncement from the NIH. So I want to get that out there right now. Dr. Brown, thank you for joining us.

Jeremy Brown 1:38

It’s my pleasure. Delighted to be on the show.

Scott Rank 1:40

Yeah, well, I really curious about how Spanish Flu compares to Coronavirus because that is what everyone is talking about right now. And I hope at least we can see that our forefathers had it much worse than we do today.

Jeremy Brown 1:54

No question that we should be very grateful that we are facing a virus today and not the virus. He said that our grandparents and great grandparents faced just over 100 years ago, and we’ll get into why very soon.

Scott Rank 2:06

And I want to get we’ll get all into the historical facts. But this is something I’m curious about, because what everyone wants to know from experts what’s going on with coronavirus? And again, I’m not going to hold this to you because I know that we can’t know for sure. But let’s say the Spanish Flu was on a scale of one to 10 at 10 of its destructive potential with the coronavirus, once the flu season comes to an end. And again, I won’t hold this to you down the road. But how dangerous would you place it on that scale?

Jeremy Brown 2:38

Well, there’s no doubt from all the numbers that we’re seeing that we’re in the middle of a story that’s still unfolding, that there is a large now there are many people are going to be affected by this, if not perhaps medically, then in many other ways that businesses are going to take a hit. Their kids may be off at school. So I think the story of coronavirus is still unfolding as We’ll discuss. There are many ways in which it was similar to what happened 100 years ago. But as I said, fortunately, we’re in a very different time in place today. And I think that overall, I certainly personally remain optimistic about coronavirus. I think that if it behaves as it always does, which is that it’s a winter virus that it is likely to come to a halt as the warmer weather begins. And we’re rapidly entering spring, at least here in the US. So I hope that the coronavirus will behave like it does every winter and disappear as the spring comes, but only time will tell.

Scott Rank 3:35

All right, well, let’s look into the past and see how issues like this were dealt with before. Now. 1918 is obviously not the first pandemic that occurs. There are outbreaks on a more local level, but let’s go into the past. I mean, as far as I understand, outbreaks and attempts at quarantines go back all the way to human civilization. Maybe we didn’t know the why of disease, but I thought He could deal with the how what was the typical response to an outbreak in the ancient and medieval worlds?

Jeremy Brown 4:07

Well, as you pointed out, we’ve known that diseases behave in certain ways, even if we’ve haven’t known what the cause is. And there’s no doubt that we had no idea what the cause of influenza was just to remind people. The word influenza comes from the Latin influential, meaning influence. And it reminds us that once upon a time, people thought that the symptoms of the disease we call influenza were caused by the influence of the stars and the alignment of Saturn and Jupiter. And that really goes to the core of this question of what’s causing the disease. As I said, even as far back as the 1918 outbreak, they had no idea what the cause was. When we go back further into history, as you pointed out, and quarantine and responses to plague have been around for as long as we have recorded history, certainly in the medieval times the Middle Ages, as you know, well from your own work. The people were put in quarantine villages were put in quarantine. And the word itself reminds us that it was this idea that you put people in, you isolate people for 40 days, quarantine during the remaining 40 days in Italian. This was these were this was a means of isolating people during the episodes of epidemic plague that were around in the 1314 1500s. But if we go further back in time, perhaps the earliest recollection that we have in the history of the of influenza is all the way back to two cities, who compiled his history of the Peloponnesian Wars between Athens and Sparta, and he wrote a three-year plague struck the area in 430 BC by then 10s of thousands of refugees had entered into Athens seeking shelter and protection. In this overcrowded city, these were the optimal conditions for an outbreak and lucidity describes a fever in the head and sneezing and hoarseness. And he actually says that the epidemic killed one-third of the 13,000 soldiers stationed in Athens. And as we think about the iconic image of a Greek soldier, you know, muscular ripped with minimal armor, but maximum muscles, this disease, killed about a third of them, and then came to an end very abruptly and scholars and researchers have looked at this disease. And actually back in the 80s, a group of researchers thought that this was epidemic influenza, and they called it lucidity syndrome. So, we have to sort of be syndrome or influenza, whatever the name is, we know that this disease goes all the way back to the very earliest records that we have in history. And of course, it predates the times that we were writing about it.

Scott Rank 7:00

It’s interesting. You mentioned that statistic, one third because I believe that’s how much the population of Europe is wiped out by the plague in the 14th century, is that about the maximum level of the proportional death toll that you have seen from the historical cases you’ve looked at? Or have there been deadlier outbreaks that could wipe out 50 70% even higher?

Jeremy Brown 7:22

It depends on sort of what level you’re looking at. So let’s think about the great influenza pandemic of a century ago. So globally, we know that it wiped out 50 to 100 million people here in the US, it killed 675,000 people 100 years ago, proportionally speaking today, that would be 3 million deaths. So it sounds like a lot. It is a lot. But we also know on the best records that we have historically, that the great influenza epidemic had a death rate of about 2%. Now that’s way higher than normal influenza, but it has a death rate of 2%. So when we hear about villages towns that were wiped out with, you know, a third of their population being killed. That’s an enormous number. And so while on a global scale, the influenza epidemic of 1918, only killed and I use the word only very carefully but killed 2% of the population in some places. It was absolutely far more of a problem. And I’ll just give one example in the inner width village of threading in Alaska. We know that that village had 80 villages in it, of whom 72 were killed, and only eight managed to survive the influenza epidemic. So you have global statistics getting slightly different numbers, but overall, it was a debit. Excuse me overall, it was a devastating pandemic.

Scott Rank 8:44

Absolutely. It killed 50 million, is that correct?

Jeremy Brown 8:47

Between 50 and 100 million people will never know exact figures are, as I said, 675,000 in the US perhaps some 20 million people in India alone. These numbers are so hard to wrap our heads around

Scott Rank 9:00

To do a little more to set the stage for the world of 1918, before getting into Spanish flu, I want to give doctors back then a little bit of credit because as we discuss this, it’ll sound like they are terribly ignorant and they’re doing all the things that you shouldn’t be doing. And in fact, they’re doing the things that you would do if you want the diseases spread as far as possible. However, to give them credit, when I’ve seen doctors in the ancient world like Galen or Hippocrates, or I’m a big fan of Abba, Senna, I’m surprised at what they’re coming up with when they have no concept of germ theory or viruses where they’re deducing just from firsthand experience, heart disease strokes, have you come across things whether the 1918 year before that surprised you with Wow, that is a remarkably good educated guess when they would have no empirical reason to know that one way or another.

Jeremy Brown 9:51

I have but I will. I will say this that I think when they got what they got right was often a lucky guess.

Fortunately, what they got wrong was often far greater. And, you know, if you think about eating theories of how of conception, for example, there was no like, there was no idea right that the woman contributed anything. There was no idea that she had an egg inside her. It was thought that of anything she contributed it was the blood that came out as menstrual blood. That was what the woman contributed to the formation of an embryo. So there’s an example of getting the anatomy and the and the science completely wrong. It’s true, Scott, that sometimes they hit on something that we might, we might understand. In fact, the Bible itself talks about putting somebody removing somebody from the camp who was exhibiting a disease, which may or may not be leprosy. It’s not clear, removing them from the camp for seven days and then revisiting them. So did they have an understanding of germ theory at the time? I think this is more of a lucky guess. I mean, if you think about it, it wasn’t in the 17th and 18th-century doctors really Really, were just coming to grips with the idea of germs and, and the medical establishment at the time famously thought that it was all nonsense. There was no need to wash your hands after you went to the dissecting, you know from doing your anatomy dissection to treating patients. And so yeah, I think it’s probably more of an of happenstance and good luck they came across there is that today we might say, huh, that’s interesting. They figure that out. But I don’t want to disappoint you because I know you have some of these people I mean, I mean a great deal.

Scott Rank 11:33

All I can say is, I mean, the four humors when you first learn about it, it sounds very strange, but I wouldn’t have been able to come up with something so elegant. But I would have come up with something cruder like okay, let’s throw a tribesman into the volcano and the sun god will be happy is what I probably would have come up with.

Jeremy Brown 11:50

Right but it’s fascinating to think just so the four humors, right? It’s a very elegant theory, of course, completely misguided and has no basis in science whatsoever. But this gave rise to the idea of bloodletting that if you could remove to the blood, you could treat the patient again, no basis in science. It’s true. There’s a couple of very rare and you know, unusual diseases in which you do remove people’s blood, but as a treatment for all diseases, it doesn’t work. And yet, this is remarkable. I found in my research when I was writing the book on influenza, that all the way up until 1918, bloodletting was being carried out as a treatment for influenza. That the Yeah, in 1916, there’s a paper that’s published by a group of British doctors when they described treating the complications of an influenza outbreak on the British troops, and they say we tried bloodletting. And remember, bloodletting now has been around for about two and a half thousand years, certainly since the time of Hippocrates. And they said we tried bloodletting. It didn’t work. No great surprise there. But okay, it didn’t work. And then they say this, they say, and the reason it didn’t work is probably that we didn’t try it. early enough. Now that’s what’s remarkable number one is that they were actually still trained, they were still doing this intervention, two and a half thousand years after it first been put out. And second of all, that they thought that it was still something that if only they did it sooner, that it would really have made an effect. So these ancient ideas for humans that you mentioned, they result in therapists which actually lasted a couple of thousand years. Interestingly, the report of these British soldiers treating patients with complications of influenza by bloodletting was published in a journal that’s still published to this day, a very well respected journal published in London called ready for this, the Lancet, the Lancet, based on the tool that originally was used to let blood so to this day are still feeling the reverberations of all kinds of things that took place in history, and we’re now still reaping the rewards of those historic, historic things.

Scott Rank 13:54

Okay, well, I love factoids like that. So thank you. And that brings us to an interesting point of where are we? What is the world of medicine in 1918? Because it’s not the Middle Ages, scientists are beginning to understand bacteria, or I don’t know if they’re so calling them Animolecules at this point, but they’re making observations of microscopes. But we don’t have vaccines if I have my timeline, right, and your understanding of viruses. So where are we in the world of 1918? And how much better is it then if you were simply in the Middle Ages and reading Galen?

Jeremy Brown 14:25

Yes, I think we are in somewhat of a better place. So we are now in the era of antiseptics List of probably, you know, in the 1870s with his introduction of antiseptics, probably, at least some historians of medicine have said it basically there’s one period of medicine from Hippocrates until the introduction of Lister, you know, some 2000 years later, introduction of Western antiseptics and basically everything is the same until then. So we are in the as we would say the modern era back but we do have a concept vaccination. I mean, we go back to Edward Jenner, and his vaccination for smallpox in the 1770s. And earlier, actually, it turns out that vaccines have been around certainly since the 10th century, there’s evidence that the Chinese were vaccinating against smallpox using a very similar method to the methods of Jenner inoculating with with cowpox. And so we’re in an area and excuse me, we’re in an era of vaccines, we still don’t really have a good sense of exactly how all these things work. We understand pasteurization because that was introduced by Louis pester in the late 19th. the century about the 1880s, somewhere like that, but we still don’t have any clue about the about viruses. Now, the word virus had been out there for centuries, a virus the word virus meant a poison. So you could do you could talk about something as a virus, meaning it was some kind of poison but the idea of virus As these very tiny creatures about a 20th, the size of a bacterium that causes a disease that was simply not known until really the 1930s. And we are still in an era, as I talked about in the book where animals bloodletting and whiskey, our main, our, you know, our treatments for influenza. So, things were better, but not a whole lot better.

Scott Rank 16:23

We don’t know where Spanish Flu begins if I have it correct. But what are some theories on that?

Jeremy Brown 16:29

Well, first of all, let’s remind everybody where it didn’t begin. So Spanish Flu did not begin in Spain. The reason that we hear about the word Spanish flu is this during the Great War During World War One, there was a tacit agreement between the governments of the allies, including the US including, Great Britain and others, not to talk about the epidemic of influenza unnecessarily not to cover it in great detail. And now certainly there are historic records and I’ve looked at many newspapers from the time In which, in which influenza appears on the front page of the newspaper. But there are many more examples in which the whole topic of, of epidemic influenza is really either not discussed at all or in the very back page. And the reason that we get this word, this term, the Spanish influenza is to just remind everybody, Spain was neutral in the First World War. And so its press was relatively more free to discuss things including the outbreak of influenza in Europe than one newspaper elsewhere. And so the first reports that we have of influenza in early 1918, spring of 1980, these actually come from Spanish newspapers, which meant now that when these were reported secondarily, people refer to it as Spanish influenza, when in fact all they were saying was influenza that was reported by newspapers in Spain. So what we have gone back then, is this idea that that Spanish influenza certainly didn’t come from Spain. But was first reported there. So where did it come from? There are three main theories. The first theory is that it was cooked here in the good old US of A. And the suggestion here is it came from a place called Haskell County,, in Kansas. There in Haskell County, there were Haskell counties, or a large county some 1700 square miles in rural Kansas, and a physician, their physician there, noted that on one day in January or February time 1918, there were 18 cases of influenza and three deaths. And he several months later reported this, but the suggestion is that Haskell county might have been the epicenter of the epidemic. And it kind of makes sense because as I said, it’s a farming community, lots of animals and we know that animals play an important part in the transmission of influenza, from the birds who originally Had the virus to humans through an intermediate animal, probably a horse or a cow, or excuse me, probably a horse or a pig. So the first theory is that it was in Haskell County. And from there, it’s spread out into local army bases camps, and from there to the rest of certainly the United States and Europe. That’s one theory. There are two other theories. The second theory is that it actually probably first occurred somewhere in the army camps in France in 1916.

The suggestion here is that again, there was close mingling between troops and animals, pigs, and allow the virus to travel from, from birds into pigs and then into us. And the support for that is really this that when the virus actually broke out worldwide in 1980, it was all over the world very quickly in an era where there was no international travel. So how did it get there how to get to places like China and Senegal. And India in the United States. So quickly the answer, according to some people is that it was actually there in 1916. During that sort of a smaller epidemic, and it sort of seated across the rest of the world, to flare up at all different places in 1918. So that’s the second theory, Northern France. And briefly, the third theory is that it came actually from China. We know that probably 140,000 Chinese workers were brought to serve in a support role on the battlefields of Europe. And in early in 1918, there were reports of an influenza type disease spreading from China. So the third theory is that it came from China. So these are the three theories, there is support for each of them. There are problems with each of them. We’ll never know for sure.

Scott Rank 20:49

What I’m curious about is, why did this happen in 1918, and not some other time because influenza isn’t new, it goes back to the beginning and maybe even predates humanity. I don’t really know how Influence works with simians. But was it because you had this primitive type of globalization with steamships and railroads in a way that connects a world that wouldn’t have in the early 1800s? But you don’t have the way to prevent it? Or is it something else? Like why is it 1918? where does this happen?

Jeremy Brown 21:18

Well, if you can answer that question, you can answer the key question that that really epidemiologists have been grappling with ever since, which is could this happen again? In other words, if we know exactly why 1918 and not 1917 or 1919, then can we know the factors and can we prevent it from happening again? So first of all, there have been epidemic influences of the centuries they depending on how you define the word and epidemic and exactly how you define, you know, the flare-up, they can be every anywhere from every 20 to every 50 years, there was a particularly bad influenza epidemic, for instance, in 1889 that affected both Great Britain and the United States. With many, many deaths, sort of a minor flare-up since 1980, we’ve had outbreaks of influenza across the world in 1957. In Hong Kong, we had an epidemic of, we should say, a near epidemic of swine flu in 1976. It was actually the threat of an epidemic, but it never materialized. We, of course, had swine flu in 2009. So, there have been many, many epidemics of influenza. Why this one was particularly bad, is really still a challenge to say, certainly the overcrowding in of the troops as they as they went back and forth, from Europe into, you know, from the battlefields of Europe, back into the United States back into Great Britain, and other places play it played a role. There was also a great deal of overcrowding in tenement buildings. As you can imagine a big influx of refugees from Eastern Europe. Perhaps it’s really difficult to say exactly what was the critical factor that made it flare up in 1918? Perhaps it was sort of all of the above. We’ll never know for sure.

Scott Rank 23:10

You mentioned the beginning that there was a gentlemen’s agreement on the part of the allies in the Central Powers not to discuss it. And I’m guessing they simply wanted to go away because they have their hands full with the war. How did other authorities treat Spanish influenza? Did they ignore it, hoping that it would go away in a similar manner? What was it like from their perspective?

Jeremy Brown 23:31

Well, from the perspective of the healthcare workers, I think there was no ignoring it. And it became a public health problem very quickly. So for instance, in December of 1918, in the midst of the pandemic, which just sort of remind people that it sort of flared up in early spring of 1918, then seemed to go away in late spring, only to rear up again in a much more seemingly aggressive way in the fall of 1918 through early 1990. Anyway, in the midst of that epidemic in December Thousand public health officials gathered in Chicago to try to put their brains together and discuss what they can do and rather than ignore it, they just fully admitted that I had no idea what this was one doctor stood up and said we should call this the x germ because we have no idea what it was from. There was another physician suggested that the only way to reduce the spread was for each disease person in a diverse suit, I’m sure there were some chuckles or in the, in the conference hall as they whether they meant this real or just tongue in cheek is difficult to say. And then actually, what struck me was a statement from the Health Commissioner from Chicago who said, Look, I don’t know what’s causing this and I don’t want people to worry. So let people do whatever it takes for them to stop worrying and he was actually referencing the wearing of masks, which were very much in fashion in 19. In 18, and I’m sure many people have seen those pictures of police officers walking around in this rather flimsy clump of paper masks. But he was basically saying if people want to wear masks, and that gives them a sense of security, that’s fine. He also said from their part, let them wear a rabbit’s foot on a gold watch chain if they want as long as keep them happy. So they really didn’t sort of very hands-on as it worked trying to get this under control. Of course, the public health officials at the time were putting out notices these famous big notices saying no spitting, and wear please wear your mask. And there were also efforts to close down movie theaters and cafes and so on that, we can talk about. school districts were closed across the United States. Although interestingly, Chicago and New York two of the biggest school districts at the time, actually kept their schools open. other school districts, San Francisco Baltimore, Boston decided to close down so it you know, they’re a very Great similarities to today where we’re already hearing that some local area, county and state, and officials are taking certain precautions that other state officials in other areas might think, well, we don’t quite have to do that yet. So a lot of similarities there.

Scott Rank 26:16

I want to get into the protocol they use and what was useful, and then what was the opposite and actually cause more harm. But for somebody on the ground in 1918, was there a slow burn? Was there a did they start to realize that something was going down and then a feeling of panic broke out? Or was it just part of the difficulties of living during the Great War when if this didn’t kill you, then something else could get you? Well, it’s interesting that

Jeremy Brown 26:43

I mean, I put together the story from newspapers. And one of the things that I found that really goes to this was it was a sort of being stoic about it. I found a report accurate from the Times of London in December of 1918. And it said And this was as the pandemic is ending in the terms of London riots never since the Black Death has such a plague swept over the face of the world. Never perhaps as a plague been more stoically accepted. I don’t know if people were really stoked with accepting this thing or not. In fact, earlier this year, the medical correspondent for The Times of London, writes with clearly must have been a huge exaggeration. He describes the people who were quote, cheerfully anticipating the arrival of the epidemic. Now, nobody cheerfully anticipates the arrival of an epidemic. But I think you get a sense certainly from these, at least this British correspondent have some amount of stoicism. I think, again, we were living in such a different era, life expectancy was you know, was probably 20 or 30 years less than it is today. You could die of scarlet fever, which is a complication of strep throat just as easily as you could die from an infection if you fell off tree, you were a kid and you fell off a tree broke your arm, cut your arm, the arm got infected, we were living in the pre-antibiotic era. So surely it was a very, very different time where mortality must have been just much more part and parcel of what of everybody’s daily lives. But of course, that’s not to. That’s not to say that it wasn’t. There wasn’t a great deal of fear as the, as this influenza took hold. And I think, for me, reading these reports for me the most troubling and perhaps the scariest part of this whole thing was the fact that there were these people who did not know what it was that was causing the infection what it was that was killing them because they had no idea they thought, any, you know, for all intents and purposes, it was the alignment of Saturn and Jupiter. And this idea of not knowing what it is that’s out there getting us It surely must have been one of the most frightening aspects of the whole thing.

Scott Rank 28:57

How did politicians and public health officials respond to this? They tried to shut down schools like you mentioned, which is good. But from what I understand they did lots of things that I’m just sure exacerbated this. What was that like?

Jeremy Brown 29:11

Well, as I said, the school some districts closed down, some didn’t in some places, cafes will close in many places. Of course, the very fact that there weren’t people in the workforce meant that things closed down. So for example, the police department, the fire departments, such as they were back then had problems, you know, with the staff filling shifts, because one of the aspects of this disease that we haven’t mentioned so far is that the influenza epidemic of 1918 has a predilection for otherwise healthy young men and women, young adults. So typically influenza To this day, it affects all of us, but it’s more likely to cause complications in the very young in the elderly and those with chronic heart or lung problems. those populations are always more at risk, and that was true of 1918 as well, but the disease They also would cause more depth and more disability in otherwise healthy people, for reasons that were not fully. We don’t fully understand today. And so because of that, you had this problem with the workforce of the time. And so, for example, in Philadelphia, the telephones, the telephones, the telephone exchange, was basically working on emergency calls only. They didn’t have enough staff to route the calls you remember those pictures of it was women, it was usually women who were routing calls by plugging in the telephone cords to where you wanted your, your call to be directed. There were simply not enough people to route the calls. And so in Philadelphia, they meant they told everybody, we’re only going to route an emergency call nothing else. And so you really see it here a sense of disruption of every day of everyday life. Now, some people actually tried to what’s the right word, they try to full of steam ahead.

Despite the fact that there were these, you know that there were, these problems. And I think one example that I write in the book that really goes to this is the story of Harold, Adele. Now I want you to take your take everybody back to October of 1918. So we’re in the middle of the Great War. We are in the middle of the pandemic. And there’s a new Charlie Chaplin movie called shoulder arms. It’s a comedy about the Great War that takes place on the battlefields of France and everybody loves it and people now are leaving their homes going to see this movie shoulder arms and Harley Dale is this young 29-year-old manager of an of the Strand Theatre in New York, and he takes out a full-page ad in a magazine called the moving picture world. And in this in this magazine, he delt says that it’s true You know, he says, some theaters were shunned by, quote, panic-stricken people, but he writes in this ad he says, I want to congratulate all those who quote, take their lives in their hands to see it. And at the bottom of the ad double-underlined in a great big font. He, he cites the recommendation of the Board of Health to quote, avoid crowds. And then he writes in this add new yorkers took their life in their hands, and tack the strand theater all weeks. So here you have this, this movie manager who’s saying well done, everybody. It’s great that you came out despite the flu pandemic. It’s great that you came out to see the movie. Unfortunately, Harold, Adele did not live to see this go into print. He died from influenza a week before this ad came out. And, you know, it’s a remarkable example of the attempt to keep life going, sometimes in the face of good hygiene and good practice. And this Adele almost seems to be laughing in at The those who, who took the advice of doctors and to stay home and he said, Well, thank you all for coming. But unfortunately, he himself died of epidemic influenza before the ad went to press. So another example exam of perhaps how people are trying to keep life as going north, you know, as normal as you can, with the realization that it’s anything but normal.

Scott Rank 33:25

It’s interesting, you mentioned that influenza struck the young, which, with all the discussion around the corona virus, it’s been emphasized repeatedly that young children are almost never affected. It’s typically those with respiratory infections or respiratory trouble and the elderly. Do you know approximately what the fatality rate was of those who came down with influenza?

Jeremy Brown 33:47

We know from some records because the people who kept that will be the institutions that kept the best records with the military. And so you have records from the military of those who were sick and those who died. So we do have those records. We don’t have them from civilians, because rather like what I suspect is going to turn out today. Most people who came down with influenza didn’t make it to the hospital because they didn’t need to go again. Even though Spanish influenza had a very high fatality rate, it was only 2% or thereabouts. And so that meant that 98% of the people who came down with this disease survived, and surely the majority of those who did survive, survived at home, because number one, the hospitals were already fallen. Number two, as we’ve, as we’ve said, there was some very, that doctors had had some treatments that were more likely to do harm than good. And so we don’t know the numbers of people in you know, in total in the civilian population, who actually came down with influenza, but the rates were certainly Very high again depends on it. In some villages, it wiped out 80% of the population. In some places, far fewer, perhaps only early three or 4% of the people died from it. But in any setting it was horrible. And then the city of Philadelphia to go back there for an example. We know that they quickly ran out of coffins. We know that there were price hikes that the price of a coffin went up 600% causing the city to enact a ruling that you’re only allowed to increase the price of coffins by 20% no more, no more war profiteer. And so we know that the death rates were so so high.

Scott Rank 35:44

And with hospitals, you had mentioned that what doctors do can harm as much as they help. Was there any understanding that you need to put those with Spanish influenza in different wards than somebody who’d have a common injury or people place together side by side

Jeremy Brown 36:00

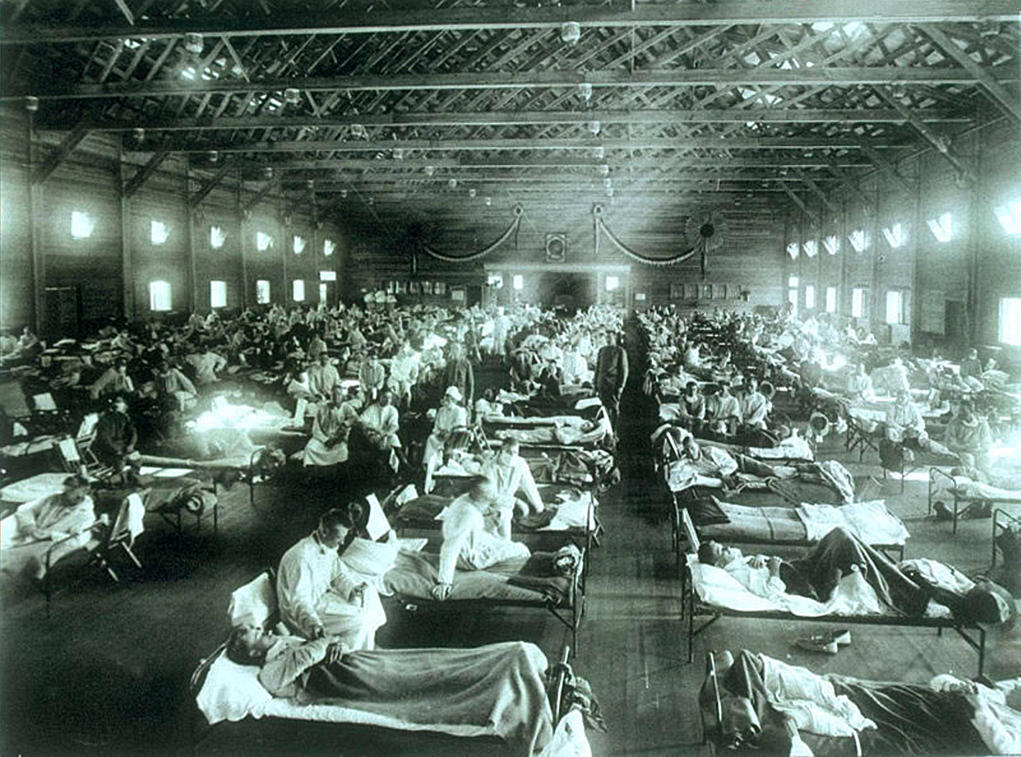

On the cover of my book is one of those iconic photos on from the great influenza pandemic. It’s of a southern influence award. And you can see there it looks like a large gymnasium a very large Stadium, there are probably a few hundred, excuse me, a few hundred people are sitting on cots, just an arm’s length from each other, you know, somebody in one bed could reach out and touch the hand of the person next to him. Some are wearing masks, some are not there is nothing between them. And this was an influenza war. This is where people who are coughing and sneezing and who had active influenza was sent to recover. And you look at that and you say it’s a wonder that any of them survived. If I was doing particularly well then I could easily pick up if not influenza than some other germ from the poor soldier lying next to me. And in some settings are on pictures like this where there is a flimsy copy cloth between the constant But overall, even though it was understood that masks have a place, and even though it was understood that we shouldn’t spit, and the last place that you really wanted to put somebody was in a ward full of other people who are coughing. And yet, that’s precisely what happened, which is why I said earlier that if you were lucky, you didn’t go to the hospital, you stayed home, and that probably gave you a much higher chance of recovery.

Scott Rank 37:22

How did Spanish influenza eventually run its course?

Jeremy Brown 37:25

In a number of different ways. First of all, as we said, a number of people succumb to the illness and those who managed to overcome the illness. And that was the overwhelming number, perhaps 98% or higher, they now had immunity to the disease. And so you couldn’t catch it a second time. You could catch a different flu virus, of course, but you couldn’t catch this particular version of the virus. So those who were a week died from it, those who survived it and now survived it. And so that was the first thing it was just and that’s true, by the way of many forms are of infection To this day, it’s sort of, we had to talk about in history, cyclical cholera epidemics of the 1600s and 1700s and 1800s. And they would often just sort of fizzle out as those who succumb to the disease died, and those who’ve gained some kind of immunity survived. So there was that aspect, but I think an important aspect was simply that influenza doesn’t like warm conditions. It doesn’t like humid conditions. The same is true of coronavirus, by the way. And so, we see this every year, right? We know when the influenza season is every year, we get prepared for it. You can see the ads that come out for all kinds of medications and get your influenza vaccine and then come to the springtime, it goes away. And that’s what happened in the spring of 1918. Although it came back in the fall, and that’s what happened in 1919 as the warmer weather came in, that was Certainly still into Windows around, it did what influenza does every year, which is it gets less and less and less the warm weather sets in. And that’s what happened.

Scott Rank 39:08

You started this episode comparing this to Coronavirus based on the fuller dive into Spanish influenza. Why was it that so deadly when so far with Coronavirus, we’ll see how many cases we get. As of this recording, there are over 100,000 confirmed cases and slightly over 3000 fatalities. Was it simply because Spanish influenza was spread with almost no check whatsoever on it spreading and with Coronavirus have the same sort of death toll if it had spread in the same way? Are there differences between the two?

Jeremy Brown 39:41

Well, I think there are some very important differences between the two. First of all, we’re now living in the antibiotic era. So it turns out that we think the majority of the deaths that were caused by the great influenza pandemic of 1918 were not caused directly by the virus itself, although that was certainly received responsible for many of them, but what you had was a virus that infected people weakened the lungs and allow the secondary infection, a bacterial infection to take over and it was that secondary pneumonia, bacterial pneumonia that probably caused the majority of the deaths. Now what we have today we have a similar story that we have some deaths that are related primarily to the virus itself, but a great many of the complications are from secondary pneumonia. And today we’re living in an era where we have antibiotics. Now, of course, everybody knows that antibiotic resistance is a problem that we have to deal with. But we do have very good antibiotics today that can deal with these secondary infections. So that’s the first difference. The second difference is, of course, that we now also have medications that can target the virus itself. Now antibiotics don’t target viruses, which is why you shouldn’t ask your doctor for an antibiotic. If You have a viral infection. However, we also have antivirals.

There are a few of them may be a half a dozen or so that target the, the virus itself. To be honest, they’re not terribly good. Even the proponents of the antivirals will say that we need to have better antivirals, but we do have them out there. So we have not only medicines that can treat secondary bacterial infections, we can also have we also have medicines that can actually attack the virus itself. And the other big difference is, is that the existence of hospitals in and intensive care units that simply didn’t exist. We mentioned these enormous gymnasium filled with men. They were the troops but they were all men. These enormous gymnasium filled with men coffee on each other. Now we understand infection control, much better. And there’s no doubt that we are in a position to take care of the very sickest people in a way that they simply inconceivable 100 years ago, and again, to remind ourselves that the vast majority of people who are going to come down, to the best of our understanding, are going to have nothing more than cough and cold symptoms that will then go away. It’s, of course, the people with chronic illnesses or chronic problems, and especially the elderly, who must be very, very cautious and careful from Cova 19. But for the rest of the population, it doesn’t appear to be a particularly dangerous disease right now.

Scott Rank 42:28

Something that historians have looked at is the effects on society after something as devastating as a pandemic happens. And those who looked at the black plague argue that it’s what started the Renaissance, it broke down the medieval order and serfdom allowing the mercantile class to rise. So in Europe, you have a breakaway from feudal systems that didn’t happen in China and Japan and other places until centuries later, and they would say that is a nice result of the plague. Now, I don’t want to Talk about the sunny side of Spanish influenza, but this affected society. So what were some changes that you saw after 1918?

Jeremy Brown 43:09

You’re absolutely right. Nothing stands in isolation. And in 1918, for example, we spoke about the fact that it had a predilection for the young, otherwise healthy welcome. So many more of these people died in the plague than you would have imagined. Now, the result of that were that there wasn’t that job opened up, right. So it turns out that because so many working-age men and men and women fell ill and stopped working, there was a labor shortage. And there as a result of the labor shortage in workers who could work experienced a higher growth rate in wages. And so actually, economists have looked at this thought that the flu had a positive income on poke on per capita. Excuse me, economists who looked at this thought that that flu had a positive impact on per capita income growth, which was large and robust in the years that followed the pandemic. So that was certainly the upside.

The downside was that while individual workers may have been able to get more money, since there were fewer of them, and they were in demand. Overall, there were some businesses that were quite ruined by the play by influenza, for example, in Kentucky and Tennessee, coal mining production dropped by half. And then Little Rock by 70%, there was a decrease of 70% of income to merchants, because there were fewer people out there buying things and so on. So it really depends on which segment of the economy you’re looking at. But no doubt there was a, an influence and just to bring that up to, into the language of today and in the book, I talk about what happened after the 2014. Flu season. And, surprisingly, there was an increase in deaths in that season in the elderly. And from a pensions perspective, this meant that since there was an increased number of deaths of the elderly, it would free up about $28 billion in pension liabilities, according to at least one report, because they were no longer these elderly people who were still around collecting their pensions. And so you can see that for every bluff Duff, there can be an economic I wouldn’t say an economic upside, but there’s certainly an economic knock-on effect, whether it’s that individual workers are able to ask for more money because there are fewer of them now, or whether it’s that because in aggregate, so many of the elder population fell victim to the influenza, the governments and private pensions, no longer had to Pay them that pension and that freed up money for other things. So I have a whole chapter in the book on this business of flu, which turns out to be a major aspect of the disease.

Scott Rank 46:10

And this, of course, doesn’t end in 1918 when I was reading news reports about coronavirus, it mentioned other episodes, the 1957 pandemic or epidemic we can talk about which one it was that killed up to a million. I thought, oh, I’ve never heard about this. And every few years, you have h1 and one swine flu, avian flu that can kill either a few thousand maybe up to 10 to 20,000. But could you just touch briefly in 1957 and I think that’s an interesting case study because since we’re comparing examples in the past to today 1957 bears a lot more resemblance to today we have vaccines, better public health measures. What happened was 1957 and what does it resemble today’s healthcare system and what was different?

Jeremy Brown 46:56

Yeah, so 1957 and I talked about this in the book of As the in the opening of a chapter on, as you said the Epidemics that followed 1918. So 1957 was a half a lifetime away from 1980. And in Hong Kong, about 10% of the population that was then two and a half million became sick, allow a large number of refugees from Communist China at the time. So it was a very overcrowded situation. And there was an outbreak there of influenza that was different to 1918. It was labeled h two n two, so it had different genes in it, but it too, was a combination of the human flu and an avian or bird flu. That infection was thought to have come in originally from ducks into us, and it didn’t stay local. And as we know, all these epidemics, now, they can start locally, but they’re spread internationally very quickly. This Asian influenza, as it was called, at the time invaded England. We think it killed perhaps 68,000 people in the United States and perhaps 2 million people Worldwide, but as you pointed out, it was more like the influences of today for two reasons. And number one, we’re now in the antibiotic era, antibiotics have been discovered in the, you know, in the 30s. There are clinical trials in the 40s. And the first patients receiving them in the 40s and 50s. So we’re now clearly in the antibiotic era, and we’re also now in the era of vaccines. So once we had discovered the cause of influenza, once we took pictures of the virus in the 40s, doctors were able to really hone in on the Cause once you know the cause, you can develop a vaccine, which is what happened. So 1957 is another example of an influenza pandemic epidemic pandemic, which affected a great many people but now was in a different era, an era of antibiotics and vaccines, where perhaps the death rate would have been far, far higher, had these not existed.

Scott Rank 48:59

So what do we do today? 1918 then these other pandemics that come afterward, what were lessons that we learned from them that we have either successfully or partially successfully been able to implement. So it’s not nearly as terrible as it was back then.

Jeremy Brown 49:14

You’re absolutely right, it this. The outbreaks that we’re seeing today, thankfully, are not nearly as terrible. But there are a number of lessons that we’ve learned. So we’ve learned from not only 1918, but ongoing viruses and viral infections, a number of things. First, the first lesson that we’ve learned is that we face real threats from these kinds of viruses that come out of in nonhuman animal reservoir, whether they’re bats, which is Coronavirus, or whether it’s ducks, or birds or pigs, which has various kinds of influenza virus. And these germs these viruses are out there lurking and it doesn’t take very much for the right conditions to occur and for them to spring into the human population, but that means that we must remain ever vigilant. And of course, it means that we have to allow both the clinical scientists people doing research, with vaccines in populations and with medicines and populations and also the basic scientists, people doing research in the laboratory on cells, we must make sure that they’re given the opportunity and the funding to carry out their research and I think Coronavirus is a really good example because Coronavirus before we had this, this new Coronavirus, Coronavirus is a common cause of the common cold. Many of the people listening to this podcast will have had a Corona virus in their sometime in their life, simply because they once come down with a cough or a cold in the wintertime and who hasn’t and perhaps 15 to 20% of those viruses. Excuse me. Those columns are caused by a coronavirus.

So it’s a common thing until suddenly it changes a Little bit. And we have to, I think, really make sure that the people working in the labs get the support that they need so that they can sort of focus on these relatively obscure viruses that people might pause and say, Well, why are you working on that virus? That’s not a dangerous virus. But the truth of the matter is that it can, it can, it doesn’t take very much for that virus to become something that becomes life-threatening. So I think the lesson there is that we must keep our eye on the ball and make sure that we really support the research that is needed. And just one more there are many, there are many more examples. But just one more thing that I think we really need to bear in mind is that the science changes. And the example I like to give on this is what happened with Ebola. So in 2014, one of the nurses Nina Pham, who was treating one of the victims of Ebola in Dallas, Texas, actually contracted the disease and came to the NIH where she was successful. So he treated them. On the day that she was released. Dr. Anthony Falchi walked out to a press conference with her. And he had his arm around her in 2014 in this in this press conference, and it was a wonderful moment because he was what he was cleverly doing was with this picture that’s worth 1000 words. He was telling everybody, look, she had Ebola. She’s not contagious anymore. I have my arm around her. It’s okay. And it was a very, very clever thing to do. And on that day that she was released, the NIH put out a press release saying we would not release the patient. Well, we’re not 100% convinced that she was she no longer had any virus in her essentially, that’s what the press release said. And that was true at the time.

But here’s the thing, Scott, six months later, there was a report in the New England Journal of Medicine, where doctors had isolated Ebola virus in the eyes and the retina of a patient who was cured of the disease and the lesson here is that the science changes. It’s absolutely true that at the time that Nina Pham was released from the NIH, the statement that she has no active disease, she has no virus in her whatsoever that was 100% true. But six months later, it turned out to be less true. And I’m not I don’t know whether she himself had a virus in her eye, but certainly other patients did. And so the lesson here is that with these emerging viruses in these rapidly changing situations, the science is certainly going to change. And what we understand about Coronavirus today, it’s very likely to be to change and to evolve over the next months and years as scientists do more and more work to understand the virus. And so we have to again, be humble, and realize that the science that we have today is only as good as this as the data that we have today. And things are going to change and evolve. And that’s nobody’s fault. That’s just the nature of the business.

Scott Rank 53:55

Well, your book came out in 2018. So I imagine that now it’s much easier to convince people that need of staying on top of virus research than it was back then.

Jeremy Brown 54:07

Well see, I mean, these things are sort of managed at very high levels of government. And unfortunately, the truth is that you know, budgets are limited. And if you’re going to put money into one area, you’re going to have to think about what area you’re not going to put it into. These are very, very hard decisions to make. And we’ll just have to wait and see. But certainly, the wake-up call from this outbreak is that yes, that viruses and viral diseases still remain a very important thing to do research on.

Scott Rank 54:37

Well, we have a lot of case studies from the past to understand today. And if listeners want to check this out, your book is influenza, the hundred-year hunt to cure the deadliest disease in history. Dr. Brown, thank you for joining us.

Jeremy Brown 54:50

It’s been my absolute pleasure, very best to you and I hope you and all your listeners stay healthy. Remember those common things to do wash your hands, cover your face and stay home. If you feel unwell.

Cite This Article

"Coronavirus is Nothing Compared to the 1918 Spanish Flu" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

April 25, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/coronavirus-nothing-compared-1918-spanish-flu>

More Citation Information.