The following article is an excerpt from Warren Kozak’s Curtis LeMay: Strategist and Tactician. It is available for order now from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

Curtis LeMay, the Air Force General and father of the modern Strategic Air Command—who turned it into an effective instrument of nuclear war—was thought by many to have a paranoid style.

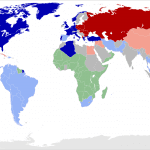

He developed an elite corps of military police to protect SAC bases, always afraid of the possibility of a domestic attack. More than half a century later, LeMay’s Cold War mentality may appear excessive in hindsight. But it was up to a commander to think of every possible way that his forces could be immobilized. The criticism after Pearl Harbor, and then sixty years later, after September 11, was that our intelligence services had not foreseen the possible moves an enemy might make. They had not been creative in their thinking and, unfortunately, the results were national tragedies. LeMay always tried to stay one step ahead of the opposition. Fifty years later, some people dismiss his concerns as paranoia because the Cold War ended successfully for the United States. But that was never preordained, and in the 1950s and ’60s it was especially uncertain. If any of the scenarios that LeMay was concerned about actually occurred, he would have been criticized for not anticipating the unimaginable.

LeMay definitely held strong views, which he had developed over long and difficult years, not just from his experience in SAC. He was always a staunch anti-Communist, and during the early McCarthy era, before the Soviets really had any nuclear capability, he was one of those who believed that subversion was a real threat, noting, “The Russians didn’t threaten us [with nuclear weapons shortly after the war]. But I was worried about fifth column activity. Sabotage.” That’s why he pushed to secure SAC bases.

LeMay had appeared as a hero on the covers of Time, Newsweek, U.S. News & World Report, Parade, and Look in the 1940s and 1950s, but the national mood had shifted, and by the 1960s when the Vietnam war was creating a divide throughout the country between conservatives and liberals, he came down on the wrong side of the political debate in the eyes of the new generation of writers and producers who were gaining influence in the media.

There have been books written and movies made that portray Curtis LeMay as an independent force unto himself—the one breach in our constitution that the founding fathers were unable to anticipate, the one member of government with no check or balance. In Stanley Kubrick’s brilliant and frightening 1964 film, Dr. Strangelove, LeMay is seen in two characters: first the cigar-smoking General Jack D. Ripper, who sends his wing of nuclear armed B-52s against the Soviet Union all on his own because he has become completely paranoid; and then as the George C. Scott character, General Buck Turgidson, the head of the Air Force in the Pentagon who, instead of seeing Ripper’s act as a disaster, sees it as an opportunity. In the famous scene that takes place in the Pentagon War Room, the president asks for Turgidson’s assessment of the situation if the U.S. goes ahead with an all-out nuclear strike. Turgidson pushes for it, but in a bizarre moment of his own strange reality, he confesses: “Sir, I’m not saying we won’t get our hair mussed, but [we’d lose] no more than 10–20 million killed tops. . . Uh, depending on the breaks.” In the final scene of the film, the world comes to an end in a long sequence of evocative nuclear explosions to the music of “We’ll Meet Again.”

These portrayals were actually quite off the mark. LeMay answered to the Joint Chiefs and to the President. He was the one person who never forgot it and who always respected the chain of command. “Our job in SAC was not to promulgate a national policy or an international one. Our job was to produce. And we produced.”

There is a final irony to the Dr. Strangelove story that does involve Curtis LeMay. Up until 1957, U.S. nuclear weapons actually did not have an effective safety net, and in some cases just one person had access to a weapon. That means one man could have possibly triggered an unauthorized detonation on his own. This was noticed by a young researcher at the Rand Corporation named Fred Ikle. Ikle raised this potential problem in his first briefing to a group of generals at the Pentagon. “My knees were shaking,” Ikle recalls, looking back over half a century. None of this seemed to interest the people who were present, except for a colonel who thought his boss would want to know about it. That colonel’s boss was LeMay. “Luckily General Curtis LeMay, who was not at the meeting, got wind of it and it hit him. He got moving on it and he changed the procedure,” Ikle explained. Because of Ikle’s observation and LeMay’s ability to move mountains, U.S. nuclear weapons thereafter were under the direction of two-man teams, adding one more crucial safeguard.

“He had a competence in getting things done,” recalls Ikle. “Today, all you have are meetings and then meetings about meetings.”

Contrary to popular perception, LeMay never stepped outside the chain of command or even tried to advance his personal views. As he later wrote, “We in SAC were not saber-rattlers. We were not yelling for war and action in order to ‘flex the mighty muscles we had built.’ No stupidity of that sort. We wanted peace as much as anyone else wanted it.” However, he strongly disagreed with the policy that promised the Soviets that the U.S. would never use nuclear weapons first. He believed the entire purpose of having a nuclear arsenal was its threatened use, not its actual use. And by promising not to use it, what was the sense in even having it? Despite this view, however, he stuck to his job. Years after his retirement, he insisted to biographer Thomas Coffey that he never advocated preemptive war with the Soviets, saying, “I never discussed the problem with President Truman or with President Eisenhower. I never discussed it with General Vandenberg when he was Chief of Staff. I stuck to my job at Offutt and in the Command. I never discussed what we were going to do with the force we had or what he should do with it, or anything of that sort. Never discussed it with topside Brass, military or civilian.”

Over the past sixty years, political beliefs have changed remarkably. In 1945, an astounding 85 percent of the American public supported the use of the atomic bombs on Japan (practically a quarter of the population—23 percent—thought even more atomic bombs should be dropped). By 1995, those who favored the use of atomic bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki dropped to 55 percent. The celebrity general on the cover of Time magazine in August 1945, who had also been brilliantly and heroically profiled in the New Yorker just two months earlier, had become a demonic clown in the eyes of many Americans by the 1960s.

LeMay saw the fascist and then Communist enemies he faced throughout his career as the same schoolyard bullies who would not listen to reason until brought to it by force. “I can’t get over the notion that when you stand up and act like a man, you win respect . . . though perhaps it is only a fearful respect which leads eventually to compliance with your wishes. It’s when you fall back, shaking with apprehension, that you’re apt to get into trouble.”

To LeMay, SAC was the sheriff who protected the small western town. It was the cop on the beat. He truly believed SAC’s motto:

“Peace is our profession.”

This article is part of our larger collection of resources on the Cold War. For a comprehensive outline of the origins, key events, and conclusion of the Cold War, click here.

|

|

This article is from the book Curtis LeMay: Strategist and Tactician © 2014 by Warren Kozak. Please use this data for any reference citations. To order this book, please visit its online sales page at Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

You can also buy the book by clicking on the buttons to the left.

Cite This Article

"Dr. Strangelove’s Real-Life Air Force General: Curtis LeMay" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

April 24, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/dr-strangeloves-real-life-air-force-general-curtis-lemay>

More Citation Information.