After a cautious start in 1861 and early 1862, President Lincoln president began moving toward the use of the slavery issue to weaken the Confederacy. His caution was due to fears of losing the border states, especially Kentucky, to the Confederacy (the rocky rollout of emancipation was one of the major causes of the Civil War). On April 16, 1862, however, he signed into law a bill abolishing slavery in the District of Columbia. After taking unsuccessful soundings among border state leaders on some kind of gradual emancipation compromise, Lincoln moved toward more direct emancipation. Following weeks of drafting, he unveiled his first official draft of an emancipation proclamation to his cabinet on July 22. It proposed January 1, 1863, emancipation of all slaves in Rebel-controlled areas. Only Postmaster General Montgomery Blair opposed the proposal, but Lincoln concurred with Seward’s recommendation that its issuance is postponed until some military success occurred that would help avoid the appearance that the proclamation was a measure of desperation.

Exactly a month later Lincoln wrote a famous letter to editor Horace Greeley responding to a pro-emancipation editorial and explaining his wartime priorities and his position on slavery. He proclaimed that Union preservation superseded slavery as the most important official issue for the president although he personally desired the end of slavery:

I would save the Union. I would save it the shortest way under the Constitution. . . . If there be those who would not save the Union, unless they could at the same time save slavery, I do not agree with them. If there be those who would not save the Union unless at the same time they could destroy slavery, I do not agree with them. My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union and is not either to save or destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that. . . . I have here stated my purpose according to my view of official duty, and I intend no modification of my oft-expressed personal wish that all men everywhere could be free.

Lincoln historian Harold Holzer, however, said that Lincoln, knowing that he had a drafted emancipation proclamation ready to issue when a Union victory occurred, was taking advantage of a Greeley-provided “opportunity to couch his forthcoming order as a matter of military necessity, rather than a humanitarian gesture, which would have elicited far more opposition.”

Lincoln and Grant, meanwhile, were developing a common interest in providing blacks with an opportunity to actively participate in the war.

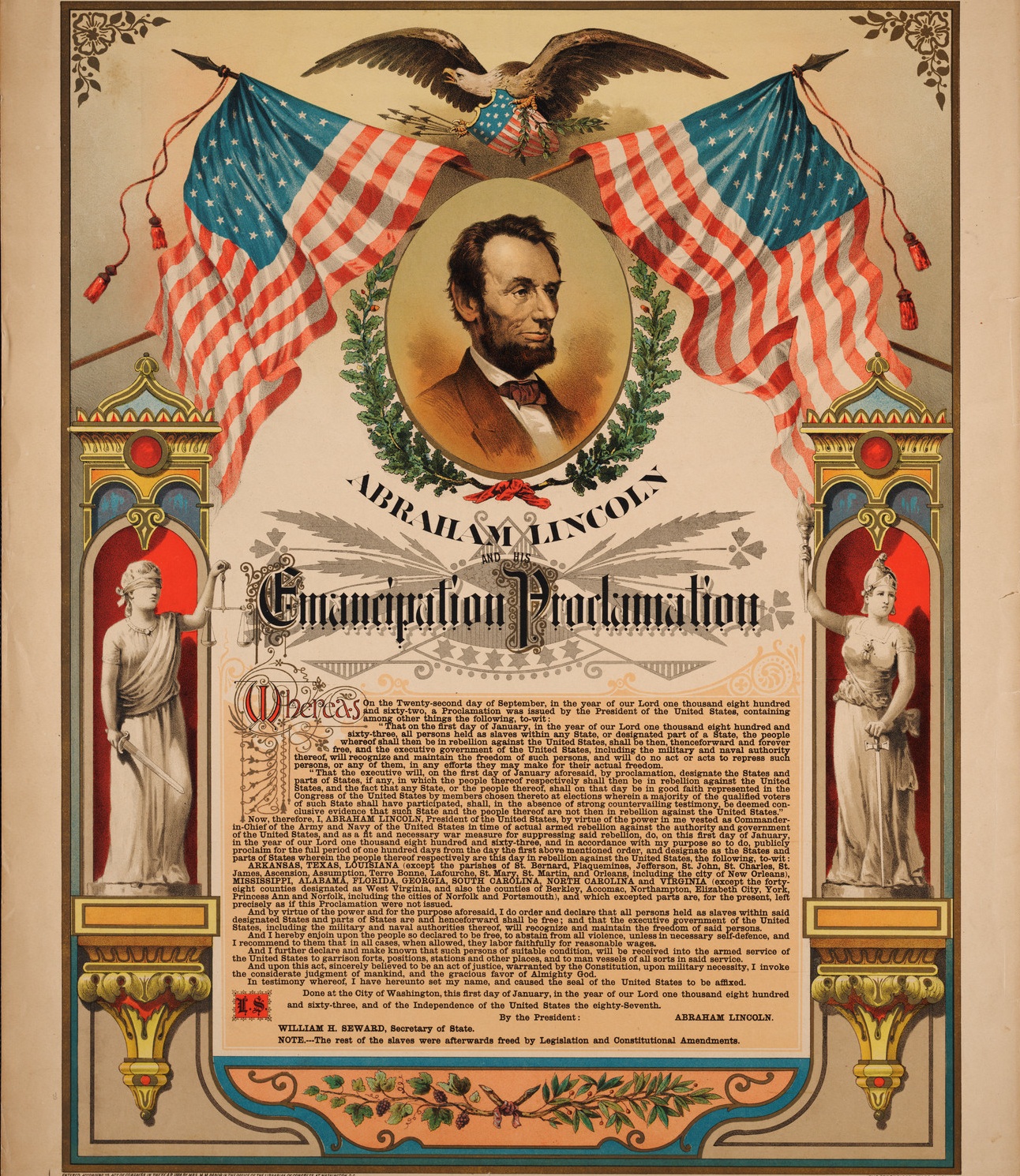

EMANCIPATION PROCLAMATION: LINCOLN FREES THE SLAVES

Lincoln appears to have taken an early step when, apparently in July 1862, he authored a memo supporting the military recruiting of free blacks, slaves of disloyal owners, and slaves of loyal owners if the loyal owners consented. He even consented to recruit the latter slaves without their owners’ consent if “the necessity is urgent.” It is possible he wrote this document in conjunction with the July 22 cabinet discussion of emancipation and recruiting of blacks. Recruiting of blacks began that month under the authority of the Confiscation Act and an act amending the Force Bill of 1795, both pushed through Congress by Republican Radicals and then approved by Lincoln on July 17.

When a Louisianan complained that the Union army’s presence in Louisiana was disturbing master-slave relationships, Lincoln, on July 28, explained, “The truth is, that what is done, and omitted, about slaves, is done and omitted on the same military necessity. It is a military necessity to have men and money; and we can get neither, in sufficient numbers, or amounts, if we keep from, or drive from, our lines, slaves coming to them.”

Grant, commanding in western Tennessee and northern Mississippi, received from General-in-Chief Halleck August 2, 1862, orders taking an aggressive position on the issue of unfriendly, slave-owning locals. Halleck ordered Grant to “take up all active sympathizers, and either hold them as prisoners or put them beyond our lines. Handle that class without gloves, and take their property for public use. . . . It is time that they should begin to feel the presence of the war.”

However, Lincoln had not concluded that the time was ripe for use of blacks as actual Union soldiers. The New York Tribune reported that on August 4 Lincoln met with a delegation offering the services of “two colored regiments from the State of Indiana” but “stated to them that he was not prepared to go the length of enlisting negroes as soldiers.” Lincoln supposedly stated that he would employ blacks as laborers but not necessarily as soldiers. The article concluded that he would only arm blacks if a more pressing emergency arose because he did not want to lose Kentucky and “turn 50,000 bayonets from the loyal Border States against” the North.

Lincoln was more philosophical than the down-to-earth Grant. In September 1862, as he anticipated issuing his Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln wrote, “The will of God prevails. In great contests, each party claims to act in accordance with the will of God. Both may be, and one must be wrong. God cannot be for, and against the same thing at the same time. In the present civil war, it is quite possible that God’s purpose is something different from the purpose of either party….” But while “Lincoln undoubtedly believed that [emancipation] was God’s will . . . he also believed in the adage that God helps those who help themselves.” Therefore, he issued his Emancipation Proclamation. It was the culmination of his pragmatic evolution from free-soiler to emancipationist.

Exactly one month later, on September 22, Lincoln finally went public with his Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. Seward’s precondition of military success had been barely met by the September 17 bloodbath at Sharpsburg, Maryland, the Battle of Antietam, where McClellan missed several chances to destroy Lee’s army but Lee was compelled to retreat to Virginia. Lincoln put the South on notice that continuation of the war would result in termination of its major social institution by declaring:

That on the first day of January in the year of our Lord, one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any state, or designated part of a state, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free; and the executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.

In his proclamation, Lincoln also quoted recent statutes in which Congress had prohibited military officers and men from returning fugitive slaves, made the fugitive slave retrieval process more difficult, and freed slaves of persons “engaged in rebellion against the government” or those giving aid or comfort to such persons once those slaves reached Union lines or came under Union control.

This proclamation changed the purpose of the war from preserving the Union to both preserving the Union and terminating slavery. It was a brilliant step because it precluded European intervention (the British and French not wanting to support slavery), undermined the Southern economy by encouraging slave desertions, and eventually provided about half of the 200,000 blacks who joined the Union army and navy. The major negative impact of Lincoln’s action was a decline in Northern Democratic (especially Irish) support for a conflict that could lead to black competition for whites’ jobs on the bottom economic rung. Lincoln was willing to pay that political price.

Following up on his Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln wrote to Grant and others in October urging them to cooperate with certain persons in Louisiana and Tennessee in seeking the return of those states to the Union under the “old” Constitution of the United States. In hopes that the threat of emancipation would stimulate their return to the Union, the president encouraged congressional elections in those states.

By mid-November, the president declared, “Do you not know that I may as well surrender this contest, directly, as to make any order, the obvious purpose of which would be to return fugitive slaves?” The next day, in the same vein, he told Kentucky Unionists “that he would rather die than take back a word of the Proclamation of Freedom….”

In his December 1, 1862, annual message to Congress, Lincoln thoroughly addressed the issue of emancipation. He described his efforts to find a foreign location to which free blacks could emigrate and regretfully reported that the only countries willing to accept them were Liberia and Haiti, countries to which free black Americans did not wish to emigrate. He proceeded to propose constitutional amendments that would require states to end slavery by 1900, permanently free all slaves who had been free at any time during the war and provide compensation for those emancipations.

GRANT EMPLOYS THE CONTRABANDS

Unlike McClellan, Grant immediately understood and agreed with the direction in which the president desired to take the nation on the issue of slavery and black rights. Therefore, Grant responded sympathetically to the needs of thousands of former slaves who fled into his lines in the closing months of 1862. One step he took was the designation of Chaplain John Eaton of the 27th Ohio Infantry Volunteers “to take charge of the contrabands [Union Major General Benjamin F. Butler’s term] that come into camp in the vicinity of the post, organizing them into suitable companies for working, see that they are properly cared for, and set them to work picking, ginning and baling all cotton now out and ungathered in field. Suitable guards will be detailed… to protect them from molestation.”

Overwhelmed by this unique assignment, Eaton quickly went to visit Grant at his La Grange, Tennessee, headquarters. After unsuccessfully trying to escape the assignment, which involved taking blacks away from providing personal services to Union soldiers and dealing with the complexities of cotton speculation, Eaton settled into a long and “earnest conversation” with Grant on “the Negro problem, with which thus early we had been brought face to face.” In the absence of specific direction from Washington, Grant was determined, for reasons of military necessity and humanity, to exercise “some form of guardianship” over the blacks—particularly “as winter was coming on and the Negroes were incapable of making any provision for their own safety and comfort.”

According to Eaton, on about November 12, 1862, Grant outlined how he would convert the blacks “from a menace into a positive assistance to the Union forces.” They could perform soldierly duties in the surgeon-general, quartermaster and commissary departments and build bridges, roads and earthworks. The women could work in camp kitchens and hospitals. Grant explained that performing these duties well would show that blacks were capable of being fighting soldiers and ultimately citizens.

Grant was probably relieved a few days later when his initial plans were confirmed by General-in-Chief Halleck. In a November 16 response to his November 15 request for guidance on what to do with the blacks (“. . . Negroes coming in by wagon loads. What do I do with them? I am now having all the cotton still standing out picked by them.”), Grant was advised, “The sectry of war directs that you employ the refugee negroes as teamsters, laborers, &c, so far as you have use for them in the Quartermasters Dept, in forts railroads, &c; also in picking & removing cotton on account of the Government.”20 Based on the reasonable assumption that Halleck and Stanton were reflecting Lincoln’s views, it appears that Lincoln and Grant were of the same mind about the increasing use of blacks for the Union cause as early as the latter part of 1862.

In late November and again in December, Grant issued a series of orders strengthening Eaton’s ability to assist fugitive blacks. A November 14 order directed him to take charge of all fugitive slaves; open a camp for them at Grand Junction, Tennessee, and put them to work picking, ginning and baling cotton. The order provided rations, medical care and protection for the fugitives and directed all commanding officers to “send all fugitives that come within the lines, together with teams, cooking utensils, and other baggage as they may bring with them” to Eaton. In a November 17 order, the Department Quartermaster was directed to furnish Eaton with tools, implements, cotton-baling materials, and clothing for men, women, and children.

Eaton encountered problems because, as he put it, “The soldiers of our army were a good deal opposed to serving the negro in any manner,” and “To undertake any form of work for the contrabands, at that time, was to be forsaken by one’s friends and to pass under a cloud.” In at least one instance, Grant had to personally intervene to keep a colonel from obstructing Eaton’s effort to direct a band of fugitives to his camp. When Chaplain Eaton found “contempt in which all service on behalf of the blacks was held by the army,” and Grant realized the tenuous nature of Eaton’s position, Grant reinforced Eaton’s powers.

On December 17, therefore, Grant issued an order designating Eaton as General Superintendent of Contrabands for the Department with the power to designate assistant superintendents. The blacks’ work was greatly expanded to include “working parties in saving cotton, as pioneers on railroads and steamboats, and in any way where their service can be made available.” Earnings from sales of cotton were to be provided to Eaton for the workers’ benefit. In conclusion, the order gave labor assignment control to Eaton while protecting blacks’ rights: “All applications for the service of contrabands will be made on the General Superintendent, who will furnish such labor from negroes who voluntarily come within the lines of the army. In no case will negroes be forced into the service of the Government, or be enticed away from their homes except when it becomes a military necessity.”

Cite This Article

"Emancipation and the Military Use of Former Slaves" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

April 19, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/emancipation-and-military-use-of-former-slaves>

More Citation Information.