George H. Thomas was fifteen years old when the blood-stained, drunken followers of Nat Turner raided his family’s farm. His mother, a widow, had heard they were coming and fled with her two daughters. The renegade slaves left a trail of murder behind them, and it scarred the memories of many people in Virginia and the South. But Thomas was not among them. Thomas, like many Southern boys, had grown up with black Southern boys for company, and he had an affinity for the slaves on his family’s farm. He taught them Sunday school lessons and secular school lessons. Like many Virginians, he looked forward to the day when they might be freemen. Nat Turner’s Rebellion did not change that. The adolescent Thomas had no undue fear, no sense that violent upheavals lay in store unless Southern laws kept the slaves down, no concern that educated and freed the slaves would become like the slave rebels of Haiti and plunge Southampton County, Virginia, and the South, into a genocidal race war. George Thomas was always steady as a rock, phlegmatic, deliberate, measured, and sensible.

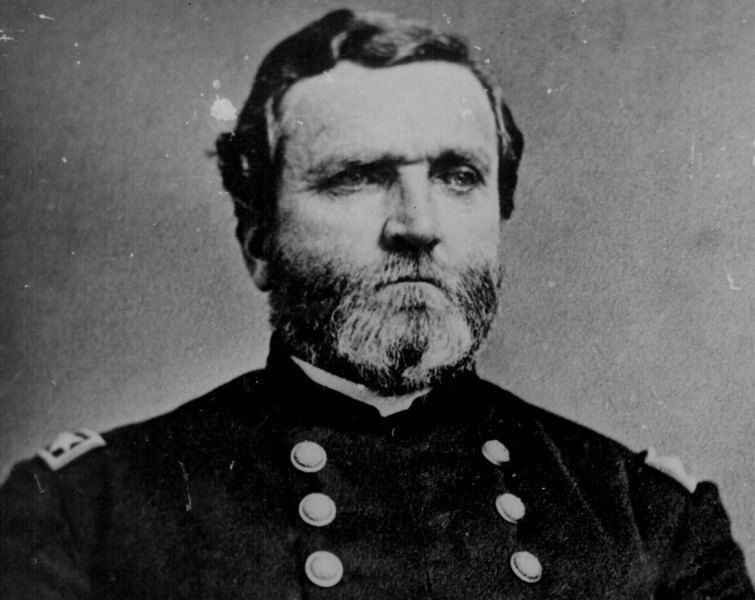

His virtues and his vices were those of a stolid man. At West Point, the young Virginian was compared to another Virginian—George Washington, to whom he was alleged to bear a striking resemblance. He was also called “Old Tom,” a young man mature beyond his years. Later, when he became a cavalry instructor, his troops knew him as “Old Slow Trot”— he was careful not to wear out his horses—and other nicknames he acquired bore a similar bloodline: “Old Reliable,” “The Rock of Chickamauga,” “The Sledge of Nashville.” He was a man of impeccable integrity, and when he was criticized it was almost invariably because impatient superiors thought that “Old Slow Trot” should be moving more quickly; this was a refrain of General Grant, who developed a dislike for George H. Thomas. But in this regard, Thomas, like the Confederate General James Longstreet, might have been slow, but he was a heavy hitter. In fact, he is probably the best Union general you’ve never heard of.

Part of the reason for his anonymity is that he never wrote his memoirs; more than that, he never sought public attention and was so correct in his character as to turn down promotions he didn’t think were merited. His CivilWar career was focused on the war in theWest, which gets less popular attention than do the dramatic campaigns of the East. But also there is this: Thomas was something of a man without a country. His sisters turned his picture to the wall and refused to acknowledge that they had a brother George. In the South, in his native Virginia, he became a non-person. But in the North, too, he could never evade suspicion of his roots, even though Thomas never showed the slightest faltering to the Union blue and even though other Virginians, including the original general

in chief of Union forces,Winfield Scott, had made the same decision Thomas did. Thomas was esteemed by most of his peers—he was one of only thirteen officers to receive an official “Thanks of Congress”—but he has been forgotten or relegated to second rank by posterity. As a boy, George Thomas was, in the words of his sister Judith, “as all other boys are who are well born and well reared.” He had taken over the leadership of the family farm when he was sixteen, worked in a law office, and, at age twenty, was accepted into West Point, where he graduated twelfth (out of forty-two) in the Class of 1840. His first assignments took him to the SeminoleWars of Florida, where his service was uneventful, and then to the War with Mexico, which was rather more so, as he saw action directing artillery at Monterrey and Buena Vista.

In the latter battle, while other batteries retired in the face of charging Mexicans, George H. Thomas kept firing until they were nearly upon him, at which point, serendipitously, other American batteries and infantry came to his aid. As Thomas remarked laconically, “I saved my section of [Brevet- Major Braxton] Bragg’s battery at Buena Vista by being a little slow.”

William Tecumseh Sherman, who was friends with Thomas at West Point, was slightly more effusive: “Lieutenant Thomas more than sustained the reputation he has long enjoyed in his regiment as an accurate and scientific artillerist.” It was Thomas’s methodical movements— which were so much the character of the man—that helped him to be such an accurate and scientific artillerist, quartermaster, and master of every other task the army assigned him. It was the Thomas way—slow, scientific, and accurate.

After the Mexican War, Thomas returned to West Point as an artillery and cavalry instructor and also managed to marry a New Yorker, which, in the coming crisis, would help solidify his Unionist sympathies.

Thomas was then sent west to California, finally ending up in the blazing desert of Fort Yuma, from which he was rescued by the Secretary of War Jefferson Davis. Davis was looking to create an elite cavalry regiment, and Braxton Bragg recommended Thomas. Thomas, Bragg admitted, “is not brilliant, but he is a solid, sound man; an honest, high-toned gentleman, above all deception and guile, and I know him to be an excellent and gallant soldier.”

The Second Cavalry Regiment had the best of everything, elaborate uniforms, and even color-coordinated horses (each company had horses of the same color). The regiment’s job was to patrol—along with the newly raised First Cavalry Regiment and two regiments of infantry—the western frontier. Among the officers serving in these cavalry regiments were Joseph E. Johnston and J. E. B. Stuart (the First Regiment) and Albert Sidney Johnston, Robert E. Lee, and John Bell Hood (the Second Regiment).

His duty in the West was much like Lee’s (he actually served under Lee), sitting on courts-martial, keeping the peace between Indians and settlers, and seizing rare chances for action (in one incident, Thomas received a Comanche arrow in his chest).

In the election of 1860, George H. Thomas did the soldierly thing—he opposed the extreme fire-eaters of the South and the rabid abolitionists of the North, and positioned himself with the party of moderation, which was represented by John Bell of the Constitutional Union Party, who carried Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia. Thomas inquired after a position (which had already been filled) at the Virginia Military Institute in January 1861, assuming apparently that his home state would not join South Carolina in secession. But when, in March, Virginia Governor John Letcher asked Thomas whether he would consider resigning his Federal commission and accepting a position as chief ordnance officer of Virginia’s military forces, Thomas declined. He did so in terms that, in due course, would cast him in opposition to Lee.

After expressing his thanks for the governor’s offer, he wrote, “it is not my wish to leave the service of the United States as long as it is honorable for me to remain in it, and therefore as long as my native State remains in the Union it is my purpose to remain in the army unless required to perform duties alike repulsive to honor and humanity.”

While Lee considered waging war against his home and native state “repulsive to honor and humanity,” Thomas, when the choice came, did not. Like Lee, Thomas opposed slavery, but he was not so opposed as to do without a black cook and a black servant (“Old Phil,” who campaigned with him in the coming war), both slaves, whom he eventually sent South, after the war, to be employed by his family.

George H. Thomas: A Humble general

Thomas clearly understood the direction the war would take. In the summer of 1861 he met his old friend William Tecumseh Sherman and the two of them bent over a map and marked out the most important strategic cities of the war: Richmond, Chattanooga, Nashville, and Vicksburg—cities that would soon be much more than mere points on a map, but targets of campaigns in which they would be involved.

Thomas earned his first general’s star thanks to Major Robert Anderson, the Kentucky-bornWest Pointer who was appointed general after his defense of Fort Sumter. Anderson recognized Thomas’s talent, but also recognized that as a Virginian Thomas was regarded with suspicion in Washington and had no politicians agitating for his advancement. The Kentuckian Anderson vouched for the skill and loyalty of his fellow Southerner and convinced President Lincoln to make the appointment. And it was to Kentucky and Tennessee that Thomas was dispatched. He was immediately victorious in his first major battle, at Mill Springs, Kentucky, but the stigma of his Southern roots remained, and theWar Department paid him no compliments.

Compliments, of course, Thomas didn’t need. He was a man of duty and a man who later in the war remarked, “Colonel, I have taken a great deal of pain to educate myself not to feel.” He got on with his work, and could remind others to do the same when they unnecessarily sought his advice or filed needless reports, telling one officer who rode up in the midst of battle to report his position, “Damn you, sir, go back to your command and fight it.”

But he was a stickler for a certain sort of protocol. His bugbear was civilian interference with military commanders, especially interference with his superior officers, to whom he was faultlessly loyal, even when he doubted them. Thomas was not a politicker; nor would he accept promotions he thought he did not merit. When he was briefly handed command of the Army of the Tennessee, he quickly relinquished it, at his own request, to General Grant (though Grant, for his part, began to develop something of a grudge against Thomas, who had been promoted after the battle of Shiloh without having taken part in it).

When Thomas received orders from Washington to take over command of the Army of the Ohio from the laggard General Don Carlos Buell, Thomas refused, thinking this was another instance of civilian interference with a commanding officer. He sent a message to the war office stating that “General Buell’s preparations have been completed to move against the enemy and I respectfully ask that he may be retained in command. My position is very embarrassing, not being as well informed as I should be as the commander of this army and in the assumption of such responsibility.”

Of this message, Thomas’s biographer Freeman Cleaves rightly notes, “Despite the extraordinary lack of self-interest, even though Thomas pleaded unfairness to himself, it was a poor excuse for a man of his caliber.

“. . .Buell maintained that he even encouraged him to accept the post saying ‘nothing remained to be done but to put the army in motion, and that I would cheerfully explain my plans to him and give him all the information I possessed.’ Still Thomas would not budge.”

The baffled bureaucrats in the War Office accepted Thomas’s demurral and thus retained Buell in at least temporary command until after the Battle of Perryville, the following month. Buell’s semi-victory there had not been enough to save him.William Starke Rosecrans took his place as commander of what became the Army of the Cumberland. Rosecrans was, however, Thomas’s junior in seniority—a problem that President Lincoln dealt with by the expedient of changing the date of his commission.

Thomas, who had willingly deferred command to Buell, felt rather differently about being passed over in favor of Rosecrans; it was a violation of protocol. But Rosecrans had always been on good terms with Thomas, and smoothed over the diplomatic niceties.

No better place to die

Rosecrans was an inspiring leader, but like many such he was prone to mood swings himself.George H. Thomas, also popular, was considered his de facto second-in-command and Thomas’s unmistakable competence and steadiness under fire soon gained him fame whether he wanted it or not. The first great battle for the team of Rosecrans and Thomas was at Murfreesboro, Tennessee (known to the Federals as the Battle of Stone’s River).

On the night of 29 December 1862, Thomas, riding the lines, heard the roar of artillery. An aide asked, “What is the meaning of that, General?” “It means a fight to-morrow on Stone River,” Thomas replied. He might have added, “Even if we are facing Braxton Bragg.” Bragg, was second only to Joseph E. Johnston in leading Confederate retreats, and Rosecrans, knowing he was facing Bragg, assumed the rebels were retiring. He was wrong, Bragg might have been a miserable officer—an officer so contentious that he was once said to have filed charges against himself—but his ill-served troops were fighters. They had bloodied Buell at Perryville and they would now put up a furious, if mismanaged, fight at Murfreesboro.

The battle began on a rainy New Year’s Eve, 1862, and was a bloody affair—Rosecrans rode about issuing orders, his uniform dripping with the blood and brains of an aide whose head was harvested by a Confederate shell. Troops hugged the ground and plugged their ears as cannonades clapped like earth-shattering thunder or bravely tried to charge though blizzards of Minié balls and canister. The Confederates had collapsed the Union lines on the first day of battle, which had the unintended effect of concentrating Federal fire.

That night Rosecrans called a council of war. His losses were tremendous (by the end of the battle nearly a third of his men would be lost as killed, wounded, or missing, more than 13,000 men) and it seemed as though retreat were inevitable. His officers were downcast when he asked their opinions. But an adjutant noted that Thomas, whose opinion Rosecrans had not yet solicited, was, “as always . . . calm, stern, determined, silent and perfectly self-possessed, his hat set squarely on his head. It was a tonic to look at the man.” His words were a tonic too. When Rosecrans asked his opinion, Thomas replied, “Gentlemen, I know of no better place to die than right here.” Those words rejuvenated Rosecrans who sprang to prepare his army for battle the next day. Union determination—and Bragg’s incompetence in the subsequent fighting—brought the Federals victory.

The Rock

An even bigger battle lay ahead at Chickamauga Creek. But first the Army of the Cumberland needed to be replenished with men and supplies.George H. Thomas’s way of training replacements was to send them into the field as skirmishers and give them a taste for combat. He, like Rosecrans, was in no hurry to pursue the rebels, remaining cautious, deliberate, and mindful always of the army’s lines of communication, which were perpetually threatened and bedeviled by the unmatchable Confederate cavalry.

By Washington’s standards, the Federal advance was terribly delayed. By Thomas’s standards, officers in the field were the only competent judges of campaign reality, and as the army’s advance would be an arduous one over mountain passes, haste was a counsel of folly. When the army did advance, it compelled Bragg to retreat.

Then there was a delay. Washington wanted Rosecrans to advance on Chattanooga. Rosecrans agreed, but not before he had secured his lines of communication and supply. He had Thomas’s assent, though Thomas was dubious about Rosecrans’s plan to divide his forces into three parts and bring them over the mountains to flank Chattanooga. That was a shade too dangerous of an approach for the Virginian who favored a deeper flanking movement that kept the army together. Rosecrans stuck with his plan and was vindicated, as Bragg retreated again—or so it seemed. Bragg was consolidating his force with that of General Simon

Boliver Buckner, and was soon to be reinforced by General James Longstreet of the Army of Northern Virginia. Though he remained skittish, Bragg recognized his opportunity to attack the divided Federals.

As it was, on 19 September 1863, Thomas wheeled out a division to attack what he thought was an isolated Confederate brigade on his side of Chickamauga Creek. The Confederates, who had crossed the creek in force, had no idea that Thomas was lodged on the extreme Federal left. A furious battle commenced, first on the Confederate right, and then down a battle line that cut through a forest broken only by occasional farms. The fighting intensified until the dead were piled like cordwood, the Creek was dyed red with blood, and the shrieking of shells, wildeyed horses, and frenzied fighting men grew deafening. The visuals were harrowing too: “Confederate artillery filled the woods with their shells which in the twilight made the skies seem like a firmament of pestilential stars,” wrote a Federal officer. “The 77th Pennsylvania of the first line was lapped up like a drop of oil under a flame.” But through the haze of battle, Thomas’s men took confidence from their commander’s unruffled demeanor. As Stone’s River had been a perfectly acceptable place to die, in his opinion, so was his current position as tenable as any. He did, however, advise Rosecrans to pull back the Federal right and reinforce him on the left; advice that Rosecrans followed as best as he thought practicable.

The next morning found Thomas in fighting spirit, and uncharacteristically animated in describing his men: “Wherever I touched upon their [the enemy’s] flanks they broke, General, they broke.” Thomas spoke “with unusual zest and satisfaction,” noted the war correspondent William Shanks. But when Thomas saw Shanks scribbling in his notebook, the forty-seven-year-old general appeared embarrassed at what might be mistaken for boastfulness, “his eyes were bent immediately on the ground and the rest of his remarks were . . . brief.”

Bragg had planned for Thomas to be the focal point of the day’s fighting, but the Confederates found more success driving at the center-right of the Union line where they exploited a gap, sweeping away the Federals, sending a flood-tide of butternut and grey uniforms surging forward, and spreading panic and confusion among the bluecoats. Rosecrans, his headquarters in peril, fled with his staff officers. The Union right was dissolved.

Rosecrans, cut off from Thomas, fled to Chattanooga in an apparent state of shock.

The Confederates broke off their assault on Thomas’s center and left, but the Union general now had Longstreet storming at his right flank. Thomas’s men took up position on Horseshoe Ridge, which they reinforced with barricades. Short of ammunition, they searched for unspent cartridges among the dead, as the enemy pressed upon them. Suddenly a dust cloud behind the Federal lines raised hope and fear—fear that beneath it was Confederate cavalry under General Nathan Bedford Forrest, hope that it might be kicked up by blue-clad reinforcements. For once in his life, Thomas appeared nervous until someone thought he saw the fluttering of the Stars and Stripes. Confirmation came as beneath the dust appeared the reserve corps of Union General Gordon Granger.

George H. Thomas now gained his monicker, “the Rock of Chickamauga.” When an aide carrying messages asked Thomas where he should find the general on his return ride, Thomas growled, “Here!” He would not be budged from this costly ground.

The fighting became a desperate hand-to-hand affair, with a Confederate lunge matched by a Federal countercharge that brought rifle butts and bayonets—not to mentions fists and rocks—to bear amidst the harsh snapping of the Minié balls. The Confederates were driven back, but they returned again and again, clawing their way towards Thomas’s shrinking line. Finally, Granger found Rosecrans and received orders for Thomas to withdraw. Rosecrans had begun writing detailed instructions as to how the retreat should be conducted, but Granger upbraided him: “Oh, that’s all stuff and nonsense, general. Send Thomas an order to retire. He knows what to do about as well as you do.” Rosecrans was too stunned to protest; it marked the practical ascendancy of Thomas over his Lincoln-appointed superior.

George H. Thomas withdrew his men in excellent order, and from the bloody shambles of Chickamauga he emerged a hero. Again he was compared to Washington. Charles A. Dana, assistant secretary of war, who was present at Chickamauga, said, “I know of no other man whose composition and character are so much like those of Washington; he is at once an elegant gentleman and a heroic soldier.” Dana’s biographer, General James H. Wilson, who served with Thomas, was of the same opinion, saying that Thomas resembled “the traditionalWashington in appearance, manner, and character more than any man I had ever met . . . and at onceinspired me with faith in his steadiness and courage.”

Thomas was, as always, popular with the troops who trusted him and knew he looked out for them. They called him “Old Pap.” His promotion, however, was stalled once more by Northern politicians loathe to promote a Virginian—and typically, when Thomas discovered that men like Dana were trying to get him promoted over Rosecrans, he interceded on behalf of his commander. Lincoln finally took the matter in hand and replaced Rosecrans with Thomas as commander of the Army of the Cumberland.

When Thomas tried to protest to his former commanding officer, Rosecrans stopped him, and told him to do his duty, as directed by the commander in chief. Thomas relented, and was now under the direct command of Ulysses S. Grant who commanded the military division of the Mississippi. Because of Grant’s partiality to General Sherman, commander of the Army of the Tennessee (Grant’s former command) it would not be a happy partnership.

Dealing with Bragg

It started in fact with whatGeorge H. Thomas took to be an insult. Having retreated to Chattanooga after the fierce battle of Chickamauga, his primary goal was to re-supply his men. Grant issued Thomas a peremptory order: “Hold Chattanooga at all hazards.” Thomas’s return message was laconic: “We will hold the town until we starve.” Given Rosecrans’s initial wires to Washington after the battle, which referred to Chickamauga as “a serious disaster” and said of Chattanooga, “We have no certainty of holding our position here,” Grant had good reason to worry. But Thomas was made of sterner stuff—and the opposing commander, Braxton Bragg, did not see fit to follow up his victory at Chickamauga with an assault on the half-starved bluecoats in this crucial city.

What awaited Thomas, instead, was a Confederate siege, with Bragg hoping to starve the Federals out rather than roust them out. The Federals, however, established a supply line—“the cracker line”—which effectively thwarted Bragg’s strategy (such as it was). Now, under Grant’s direction, the Federals began drawing up plans for an offensive to drive Bragg’s army away. Thomas disliked Bragg almost as much as Bragg’s own generals did (they had tried to have him removed from command) because Bragg had returned a letter of Thomas’s with a note insulting Thomas as a traitor to his state. Beneath Thomas’s noble countenance burned a desire to avenge himself on his former friend—and he would, as Thomas’s troops first seized Orchard Knob, his first objective, on 23 November, and then two days later made their dramatic charge up Missionary Ridge, which broke the Confederate army and put it to flight.

Hammer and Anvil: Sherman and George H. Thomas

After the battle of Chattanooga,George H. Thomas regarded his Army of the Cumberland as the force to defeat Joseph E. Johnston, who had replaced Bragg as the opposition commander. Grant, however, saw Thomas in an auxiliary role, supporting Sherman, and Sherman naturally agreed. While Thomas was one to diligently maintain his lines of communication and supply, Sherman had no qualms about cutting loose in enemy territory, planning to live off—and indeed punish—Southern civilians, and trusting that George H. Thomas could fight any grey-clads in his rear.

This is when Sherman’s and Thomas’s reputations were made: “Thomas never lost a battle” and “Sherman never won a battle or lost a campaign.” The cool-headed Thomas is usually regarded as Sherman’s tactical superior while Sherman is given credit for having a more imaginative grasp of campaign-level strategy (Sherman had, of course, the advantage of being Grant’s strategic confidant).

Grant and Sherman together held the idea that George H. Thomas—careful, methodical, and not averse to entrenching in the face of the enemy—was slow, though Thomas’s defenders would counter that he was not noticeably slower than Grant in his campaign against Lee, that Sherman and Grant routinely left Thomas as the rear guard to mop up after Sherman, and that he had to take care where the reckless Sherman did not.

The contrasting characters of Sherman and Thomas were highlighted at the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain. Thomas had advised a flanking attack on Joseph E. Johnston. Sherman insisted that his own troops would lead a frontal assault on the Confederate positions. Sherman told General John A. Logan that a frontal attack was necessary because “the whole attention of the country was fixed on the Army of the Potomac and that his [Sherman’s] army was entirely forgotten.” He needed “to show that his men could fight as well as Grant’s.”

George H. Thomas never felt the need to prove himself in this way—and his men appreciated him for it. After two failed attempts to storm the Confederate lines that cost him 3,000 casualties, Sherman withdrew for a flanking attack, but Johnston had slipped away. Sherman, however, was adamant in self-justification: “Failure as it was . . . I yet claim it produced good fruits as it demonstrated to General Johnston that I would assault and that boldly.” Thomas was more the realist: “One or two more such assaults would use up this army.”

After the Federals took Atlanta, Sherman, with Grant’s blessing, planned to let Thomas handle the wildcat Confederate army led by Kentuckian- Texan John Bell Hood, the one-legged, one-armed, single-mindedly aggressive general who had been chosen to replace the great tactical retreater Joseph E. Johnston. Rather than tangling with Hood, Sherman would mount a campaign against Southern civilians; his purpose, he said, was to make Georgia “howl”; and to achieve this high purpose he stripped Thomas’s army of some of its best units (especially of cavalry). Thomas’s task, then, was to fortify Nashville.

This he did, and when both freezing weather and the Confederate army pressed in on the city, he prepared his men for a breakout attack—again too slowly for General Grant, who perhaps did not appreciate the difficulties of launching an offensive on a sheet of ice, in freezing rain, or understand that the weather inhibited the movements of both armies. If Thomas could not move from Nashville, neither could Hood drive far around him.

When Thomas broke out of Nashville on 15 and 16 December 1864, it spelled the end of Hood’s command. On 16 December, the Yankees stormed the Confederates’ last redoubts in a scene remembered by Union General James T. Rustling: “grape and canister shrieked and whizzed; bullets in a perfect hailstorm. . . .The whole battlefield at times was like the grisly mouth of hell, agape and aflame with fire and smoke, alive with thunder and death-dealing shots. The hills and slopes were strewn with the dead; ravines and gorges crowded with wounded. I saw men with their heads or limbs shot off; others blown to pieces. I rode to a tree behind which a Confederate had dodged for safety, and a Union shell had gone clear through both tree and soldier and exploded among his comrades.”

It takes a certain sort of man to see this and remark of the Yankee cheers as the Confederate lines were taken, “the voice of the American people.” Thomas was such a man. Just as when Richmond, the capital of his home state, fell to the Federal invader on 3 April 1865 he ordered a 100- gun salute as part of Nashville’s enforced celebrations.

What sort of man relishes the destruction and defeat of his home state? Of course he had no more regard for the separate states of the North. A chaplain once asked him after a battle whether the dead should be buried in groups by state. George H. Thomas growled, “No, no, no.Mix them up. Mix them up. I am tired of states-rights.” Thomas was obviously no respecter of Edmund Burke’s dictum that to “love the little platoon we belong to in society, is the first principle (the germ as it were) of public affections.” Thomas, who had hardened himself against feeling, had no concern for states or states’ rights or little platoons, it was all mix them up, mix them up.

Punishing Rebels

George H. Thomas had no sympathy for his fellow Southerners—he thought Southern women were especially recalcitrant—and endorsed harsh measures during Reconstruction. When the Episcopal bishop of Alabama instructed his priests to omit prayers for the Reconstruction authorities, Thomas retaliated by closing down all the Episcopal churches in Alabama. He was also the military authority in charge of Tennessee, which was coerced into passing the 14th Amendment (a requirement for being readmitted to statehood in the Union) by the expedient of arresting dissident members of the legislature and forcing them to sit in the chamber so that the measure could be passed with a quorum.

Thomas’s position, vis à vis his fellow Southerners, was expressed in a letter he wrote to the mayor of Rome, Georgia, who merited Thomas’s wrath for celebrating Georgia’s secession day with Confederate flags: The sole cause of this and similar offenses lies in the fact that certain citizens of Rome, and a portion of the people of the States lately in rebellion, do not and have not accepted the situation, and that is, that the late civil war was a rebellion and history will so record it. Those engaged in it are and will be pronounced rebels; rebellion implies treason; and treason is a crime, and a heinous one too, and deserving of punishment; and that traitors have not been punished is owing to the magnanimity of the conquerors.With too many of the people of the South, the late civil war is called a revolution, rebels are called “Confederates,” loyalists to the whole country are called d—d Yankees and traitors, and over the whole great crime with its accursed record of slaughtered heroes, patriots murdered because of their true-hearted love of country, widowed wives and orphaned children, and prisoners of war slain amid such horrors as find no parallel in the history of the world, they are trying to throw a gloss of respectability, and are thrusting with contumely and derision from their society the men and women who would not join hands with them in the work of ruining their country. Everywhere in the States lately in rebellion, treason is respectable and loyalty odious. This, the people of the United States, who ended the Rebellion and saved the country will not permit.

An impassioned missive, but for all its emotion, it rather misses the point. For the bill of particulars that Thomas lays against the South could even more plausibly be laid by King George III against the rebellious American colonists; and the South at least had the precedent of 1776 to draw from as justification for its actions.

Moreover, one cannot say that the South committed treason in establishing its own republic. It did not give aid and comfort to American enemies. It merely separated itself from the United States in order to achieve, to its own satisfaction, a more perfect union of like-minded states. There is, in fact, neither crime nor treachery in that—only the democratic desire of the people of the Southern states to go their own way. The people of the South were loyal to their states and that loyalty in no way endangered the peace of those states that wished to remain part of the United States.

George H. Thomas remained loyal not to his state, not to his region, but to the United States government and its forcible subjugation of unwilling members of the Union. Thomas, and Northerners generally, assumed a moral high ground that Southerners—Confederate Southerners, that is—could regard only, at best, as brute humbug.

But it was still no doubt sincerely held. It is therefore all the more ironic that in the remaining five years of his life after the war, he continued to feel maltreated and overlooked by his superiors when it came to promotions. When Confederate general John Bell Hood met with Thomas after the war, he said “Thomas is a grand man. He should have remained with us, where he would have been appreciated and loved”—a remark so true as to deny rebuttal. One can only imagine the result for the Confederacy had Thomas held the command so long abused by Braxton Bragg.

George H. Thomas was above all a soldier. The army defined him. When he died in 1870, it was at his post in California. He was buried in New York, far from his native Virginia, attended by President Ulysses Grant, Generals Sherman, Sheridan, and Meade, and thousands of others (from the governor to a congressional delegation, to former comrades-in-arms). Since his death, he has been largely forgotten. As Grant preferred his fellow Ohioans Sherman and Sheridan, so has history.

Would you like to learn the complete history of the Civil War? Click here for our podcast series Key Battles of the Civil War

Cite This Article

"Union General George H. Thomas: (1816-1870)" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

April 24, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/george-h-thomas>

More Citation Information.