The following article on the German Navy during World War Two is an excerpt from Barrett Tillman’ D-Day Encyclopedia. It is available for order now from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

Admiral Erich Raeder, chief of the navy, was a competent officer who recognized the need for Germany to conduct a successful war at sea. Before the war he envisioned a naval construction program that would peak in 1948, at which point the Kriegsmarine would be expected to be able to accomplish its mission of isolating Great Britain from the New World. However, the fleet he advocated was conventional, oriented toward surface combatants, despite the evidence of British superiority from 1914 to 1918. German naval strategists knew that submarines lent economy of force; during the First World War some seven hundred Allied escort vessels had been occupied defending against a maximum of sixty deployed U-boats at any one time.

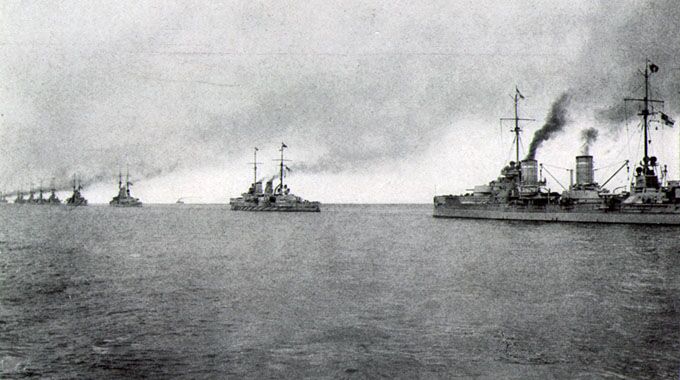

Although Raeder’s program provided for substantial numbers of submarines and even aircraft carriers, it was not the force to defeat the Royal Navy; at its peak the Kriegsmarine never possessed more than five battleships or battle cruisers, compared to Britain’s fourteen. Raeder’s astute subordinate Adm. Karl Doenitz recognized that only with a strong U-boat arm could Germany hope to win a naval war.

The narrowness of Hitler’s perceptions of naval matters was well illustrated at the end of the Scandinavian campaign of early 1940. The Kriegsmarine succeeded in transporting large numbers of German troops to Norway, but it lost thirteen destroyers in the process. Hitler is reported to have said that the operation had justified the navy’s entire existence.

Over the next two years, in contrast, the U-boat arm went from strength to strength, enjoying mounting success during what the submariners called ‘‘the happy time.’’ Allied shipping losses soared; Winston Churchill later confided that the U-boat threat was the only thing that had seriously worried him throughout the war. Meanwhile, the Kriegsmarine’s superb battleships and cruisers were rendered irrelevant through loss, damage, and inactivity.

Raeder became weary of the bureaucratic and political infighting of the Nazi regime and retired in January 1943. Doenitz was the logical successor, and in him the navy inherited a more forceful advocate. However, it was too late to reverse events already in progress. With America’s entry into the war, a massive Allied shipbuilding program was instituted that, with such British technical developments as electronic warfare and escort aircraft carriers, dramatically changed the Battle of the Atlantic. By May 1943 the previous midocean ‘‘air gap’’ in convoy coverage had been closed by carrier aircraft, and the crucial campaign was all but won. The ability of Allied convoys to travel freely between North America and Britain ensured the unimpeded buildup to Overlord a year later.

The German navy was poorly equipped to resist the massive invasion force that the Allies assembled at Normandy. A success was scored by S-boats during Operation Tiger off the Devon coast in late April 1944, but otherwise Hitler’s navy made little impression upon the huge Allied armada.

Two U-boat groups were prepared to resist Neptune: forty-nine submarines in Bay of Biscay ports and twenty-two more in Norway. However, twenty-six submarines were lost during June, sinking only fifty-six thousand tons of shipping. One boat was destroyed in the English Channel on D-Day, followed by seven more throughout the month; four were lost in the Bay of Biscay. Only one boat penetrated the massive Allied naval screen, sinking an LST before being driven off on D+9.

On D-Day German surface units sank a Norwegian destroyer, while British and Canadian destroyers sank one German destroyer and drove another ashore.

During the rest of June, the most successful German naval operations were the results of mine warfare. Eight Allied escorts were destroyed and three damaged beyond economical repair by mines, mostly from submarines or minelayers. However, German aircraft and shore batteries also contributed to the toll.

But the Allies gave more than they got. RAF attacks on Le Havre and Boulogne destroyed dozens of S-boats and small craft, and not even rail shipment of replacement boats could make up the deficit. German navy operations in the Bay of the Seine nearly ceased altogether. Although fortyseven one-man torpedoes were deployed in July, they sank only three British mine craft. Radio-controlled motorboats with high explosives also were only marginally effective.

By the end of the war the U-boat arm had sustained 80 percent losses in crews killed or captured. It was the heaviest casualty rate of any service in the war, including the Japanese kamikaze Special Attack Corps. Yet Doenitz’s exceptional leadership kept morale surprisingly high, and the German navy of 1945 experienced none of the mutinous tendencies of the High Seas Fleet in 1918.

This article on the German Navy during World War Two is from the book D-Day Encyclopedia, © 2014 by Barrett Tillman. Please use this data for any reference citations. To order this book, please visit its online sales page at Amazon or Barnes & Noble.

You can also buy the book by clicking on the buttons to the left.

This article is part of our larger resource on the WW2 Navies warfare. Click here for our comprehensive article on the WW2 Navies.

Cite This Article

"German Navy During World War Two" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

April 12, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/german-navy-ww2>

More Citation Information.