Union

Abraham Lincoln

Lincoln was assassinated on April 14, 1865, only four days after Lee’s surrender. He was 56. After a long funeral procession, he was buried near his home in Springfield, IL. He is widely considered to be one of our greatest presidents, if not our greatest.

Ulysses S. Grant

Grant remained as General-in-Chief of the U. S. Army after the war. In 1866, he became the first person ever to become a four-star general. He was nominated as the Republican candidate for U. S. president in 1868 and was elected in November of that year. He served two terms that were often plagued by scandal, although Grant himself was completely honest. After he left the White House, he moved to New York, where he lent his name to a Wall Street brokerage form. One of his partners stole millions from the firm, making Grant penniless. At about the same time as this, Grant was diagnosed with throat cancer. He spent the rest of his life working on his memoirs, dying in 1885 at the age of 63. His memoirs sold half a million copies and restored his family’s fortune.

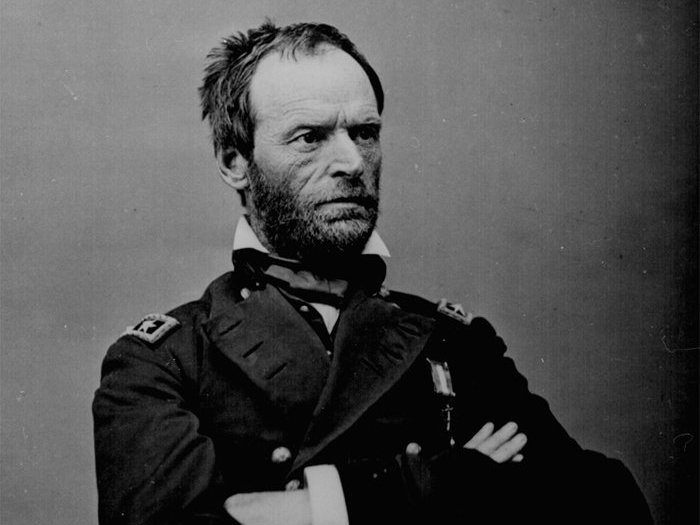

William T. Sherman

Sherman remained in the army, becoming the army’s top general after Grant’s inauguration as U. S. President. He served during much of the nation’s wars against the Plains Indians. He retired from the army in 1883. When his name was mentioned as a possible presidential candidate, he famously said “If nominated, I will not run. If elected, I will not serve.” He died in New York City in 1891 at the age of 71. One of the honorary pallbearers at Sherman’s funeral was his old foe Joseph Johnston.

Philip Sheridan

After the war. Sheridan also stayed in the Army, serving in Texas during Reconstruction. He famously said “If I owned Texas and Hell, I would rent Texas and live in Hell.” (After his death, one witty Texan replied that his body should be re-interred in Texas so that he could be in both at the same time). Sheridan later commanded U. S. Army troops that fought against Indians in the West, served as an observer in the Franco-Prussian War, and coordinated relief efforts after the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. After Sherman’s retirement, Sheridan became General-in-Chief of the U. S. army and served in that capacity until his death in 1888 at the age of 57.

George Thomas

Because Thomas, a Virginian, chose to stay loyal to the Union, his family disowned him. They turned his picture against the wall, destroyed his letters, and never spoke to him again. During the economic hard times in the South after the war, Thomas sent some money to his sisters, who angrily refused to accept it, declaring they had no brother.

After the end of the Civil War, Thomas held various commands through 1869. During the Reconstruction period, Thomas acted to protect freedmen from white abuses. He set up military commissions to enforce labor contracts since the local courts had either ceased to operate or were biased against blacks. Thomas also used troops to protect places threatened by violence from the Ku Klux Klan. In 1869, he was given command of the Military District of the Pacific, but he died one year later of a stroke at the age of only 53. None of his blood relatives attended his funeral.

Irvin McDowell

Beginning in 1864, McDowell was rotated through a series of commands, including California, the East, the South, and California again. After his retirement from the army in 1882, McDowell served as Park Commissioner of San Francisco, California. In this capacity he constructed a park in the neglected reservation of the Presidio, laying out drives that commanded views of the Golden Gate. He died of gastric cancer on May 4, 1885 at the age of 66.

George McClellan

After the 1864 election, McClellan resigned from the Army. After the war, he went abroad for 3 years. After returning to the US, he worked in several engineering and business jobs until he was elected governor of New Jersey in 1878. He served a single term as governor and then retired, devoting the rest of his life to writing his memoirs. He died of a heart attack in 1885 at the age of 58.

Ambrose Burnside

In 1866, Burnside was elected Governor of Rhode Island, serving from 1866 to 1869. He was a leader in veterans’ associations and became the very first president of the National Rifle Association in 1871. He was elected to the U. S. Senate in 1874 and served until his death in 1881 at the age of 57.

Joseph Hooker

After the war, Hooker led Lincoln’s funeral procession in Springfield on May 4, 1865. He later commanded the Department of the East and Department of the Lakes. His postbellum life was marred by poor health, and he was partially paralyzed by a stroke. He retired from the Army in 1868 and died in 1879 at the age of 64.

George Meade

Meade was a commissioner of Fairmount Park in Philadelphia from 1866 until his death. He also held various military commands, including the Military Division of the Atlantic, the Department of the East, and the Department of the South. He replaced Major General John Pope as governor of the Reconstruction Third Military District in Atlanta in 1868.

Meade received an honorary doctorate in law from Harvard University, and his scientific achievements (including inventing a hydraulic lamp for use in lighthouses) were recognized by various institutions, including the American Philosophical Society and the Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences. Having long suffered from complications caused by his war wounds, Meade died in 1872 at the age of 56, still on active duty, following a battle with pneumonia

Joshua Chamberlain

Chamberlain received the Medal of Honor for his bravery at Gettysburg, served four terms as Governor of Maine, and then became president of Bowdoin College, where he taught every subject except mathematics. After 12 years, he left the college and served in a variety of positions. In 1898, he volunteered for service in the Spanish-American War but was rejected due to his bad health. Chamberlain died of his lingering wartime wounds in 1914 in Portland, Maine, at the age of 85.

David G. Farragut

After the war, Farragut was active in veterans’ associations. He was promoted to full admiral in 1866, becoming the first U.S. Naval officer to hold that rank. His last active service was in command of the European Squadron, from 1867 to 1868, with the screw frigate USS Franklin as his flagship. Farragut remained on active duty for life, an honor accorded to only seven other U.S. Naval officers after the Civil War. He died in 1870 at the age of 69.

Confederate

Jefferson Davis

After his capture on May 10, 1865, Davis served two years in prison at Fort Monroe, VA. After his release, he lived the rest of his life off the charity of a wealthy widow and working on a massive memoir, The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government. He died in 1889 at the age of 81.

Robert E. Lee

Soon after the war, Lee swore allegiance to the Union, inspiring thousands of other former Confederates to follow suit. An insurance company offered him $50,000 for the use of his name. He turned it down, saying “I cannot accept payment for services that I do not render.” Instead, he took a position as president of Washington College, where he served until his death at age 63 in 1870. The college was later renamed Washington and Lee College (now University). Lee’s final words were “Strike the tent.”

Joseph Johnston

Like many of his colleagues, Johnston worked in the railroad and insurance industries after the war, and like them, he also wrote his memoirs. He served in the US Congress for one term (1879 to 1881) and was active in veterans’ associations.

Johnston remained highly respectful of his old opponent Sherman and would not allow criticism of Sherman in his presence. Sherman and Johnston corresponded frequently, and they met for friendly dinners in Washington whenever Johnston traveled there. When Sherman died, Johnston served as an honorary pallbearer at his funeral. During the procession in New York City on February 19, 1891, he kept his hat off as a sign of respect, although the weather was cold and rainy. Someone concerned for his health asked him to put on his hat, to which Johnston replied, “If I were in his place and he were standing here in mine, he would not put on his hat.” He caught a cold that day, which developed into pneumonia. He died a few weeks later in 1891 at the age of 84.

- G. T. Beauregard

After the war, Beauregard served as a railroad executive, managed the Louisiana State Lottery, and became very wealthy in the process. Beauregard and Davis published a series of bitter accusations and counter-accusations retrospectively blaming each other for the Confederate defeat. He died in 1893 of a heart attack at the age of 74 in New Orleans.

James Longstreet

Longstreet settled in New Orleans after the war and worked in the railroad, cotton, and insurance businesses. He became a pariah in the South by converting to Catholicism, joining the Republican Party, serving as Minister to Turkey under President Grant, and publicly criticizing Lee’s strategy at Gettysburg. He later moved to Georgia, where he died in 1904 at the age of 82. Longstreet became the villain of the Confederacy in “Lost Cause” writings. Since the late 20th century, his reputation has risen. Many Civil War historians now consider him among the war’s most gifted tactical commanders.

Jubal Early

After Lee’s surrender, Early refused to give up. He escaped to Texas on horseback, hoping to find a Confederate force that had not surrendered. He proceeded to Mexico, and from there sailed to Cuba and finally Canada. Despite his former Unionist stance, Early declared himself unable to live under the same government as the Yankee. For the rest of his life, he prided himself as an “Unreconstructed Southerner.”

Early became a leading proponent of the “Lost Cause” myth and savagely attacked James Longstreet in his writings. Early’s biographer Gary Gallagher noted that Early understood the struggle to control public memory of the war, and that he “worked hard to help shape that memory, and ultimately enjoyed more success than he probably imagined possible.” Early died after a fall in 1894 at the age of 77.

Braxton Bragg

Bragg (like many of his colleagues) served in a variety of positions in the insurance and railroad businesses, but he had a hard time keeping a job due to his quarrelsome nature. He died of heart disease in 1876 at the age of 59.

John Bell Hood

After the war, Hood moved to Louisiana and worked in the cotton and insurance businesses. He and his wife died in the New Orleans Yellow Fever epidemic in 1879 at the age of only 48, leaving 10 orphaned children. His fellow former Confederate, P. G. T. Beauregard, saw that Hood’s memoirs were published so that the proceeds could support the children. Fort Hood, a U. S. Army installation in Texas, is named after him.

Nathan Bedford Forrest

In 1867, Forrest became the first Imperial Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, but he later quit when the Klan became too violent for even him. Unlike many former Confederates, Forrest spoke in encouragement of black advancement and of endeavoring to be a proponent for espousing peace and harmony between black and white Americans going forward. Forrest died from acute complications of diabetes in Memphis in 1877 at the age of 56.

Raphael Semmes

Semmes was briefly held as a prisoner by the U.S. after the war but was released on parole; he was later arrested for treason on December 15, 1865. After a good deal of behind-the-scenes political machinations, all charges were eventually dropped, and he was finally released on April 7, 1866. After Semmes’s release, he worked as a professor of philosophy and literature at Louisiana State Seminary (now Louisiana State University), as a county judge, and then as a newspaper editor. Like many top Confederate leaders, Semmes wrote a memoir in which he advance the myth of the Lost Cause. He died of food poisoning in 1877 at the age of 67.

Would you like to learn the complete history of the Civil War? Click here for our podcast series Key Battles of the Civil War

Would you like to learn the complete history of the Civil War? Click here for our podcast series Key Battles of the Civil War

Cite This Article

"What Happened to Civil War Generals After The War" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

April 20, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/history-civil-war-10-battles-part-21-became-men-wore-blue-grey>

More Citation Information.