The saga of the Bonus Army was born out of the inequality of the Selective Service Act (1917), the failure of the government to provide any meaningful benefits to the veterans of the First World War, and the fear and anxiety produced by the Great Depression.

During WWI, for the first time in America’s history, a wartime army went off to fight composed of more than half draftees. Despite the rigorous propaganda efforts of George Creel’s Committee on Public Information, only 97,000 men had volunteered for the war three weeks after America’s declaration of war against Germany. Although 2 million men ultimately did volunteer, another 2.8 million were drafted. Draftees were organized into 4 categories, one of which exempted draftees who worked in essential defense industries. By the end of the war, these industrial workers had earned about ten times what the category I troops had earned. They had also avoided the physical, mental, and spiritual hardships of combat, and they were better positioned to survive in the nation’s shrinking economy. It didn’t take returning combat troops long to recognize the inequity of their situation. Meanwhile, Black American troops, bared from combat duty with American units, had fought in the trenches under the French flag. Having experienced a measure of equality and dignity from the French, they too arrived home with a heightened awareness of inequality.

Soon, American veterans began to argue that they should receive “adjusted compensation” for the wages they had lost while serving overseas, a term carefully chosen to suggest equality. Critics, however, were successful at labeling these veterans as “bonus seekers”, suggesting some special treatment above and beyond what they deserved. In 1924, after several years of lobbying, congress finally awarded the WWI veterans “adjusted universal compensation”—a bonus—in the form of government bonds that would collect interest over two decades and be paid out no earlier than 1945. The bill was passed by overriding a veto from President Calvin Coolidge, who remarked, “Patriotism which is bought and paid for is not patriotism.” Although the provision that allowed for the bonus to be paid immediately upon the veteran’s death earned it the nickname, “the tombstone bonus,” the veterans were satisfied.

But then, in 1929, the economy collapsed. President Herbert Hoover’s reluctance to recognize the severity of the economic crisis exacerbated the problem. Although the president ultimately did authorize some massive public works projects to put money back into the economy, it was too little, too late. By 1932 veterans, desperate for economic relief, wanted the bonus to be paid immediately. Such a bill was introduced in congress by Congressman Wright Patman of Texas, himself a war veteran. This bill caught the attention of a former sergeant named Walter W. Waters, now unemployed in Portland, Oregon. Waters grew increasingly frustrated as the bill languished, while Washington lobbyists appeared successful at procuring legislation that benefited corporate interests. On March 15, Waters met with other veterans in the Portland area, and urged them to march on Washington, D.C., to lobby for the bonus in person. He had no takers that evening, but after the bill was shelved on May 11, the Portland veterans reconsidered. Soon, about 300 of them began “riding the rails” toward the nation’s capital.

As they headed east, the media took an interest in the story. Radio, newspaper, and film crews reported on the veterans favorably. Suddenly, the Bonus Expeditionary Force (a play on the “American Expeditionary Force,” under which they had been organized in France) became a movement of hope. Veterans across the country started jumping on freight trains, sometimes with their families, and headed for Washington. They came on buses, old trucks, and even on jitney Fords with up to 20 veterans hanging off the sides of them. Sympathetic railroad men, many of them veterans themselves, refused to turn in these illegal passengers. In town after town, supporters donated food, money and moral support.On May 21, railroad police tried to stop Waters and his men from hopping eastbound freight trains just outside of St. Louis in Illinois. In response, the veterans uncoupled cars and soaped the rails, refusing to let trains depart. Illinois governor Louis L. Emmerson called out the Illinois National Guard, and in Washington, the Army deputy chief of staff, Brig. Gen. George Van Horn Moseley, urged that U.S. Army troops be sent to stop the Bonus Marchers, on grounds that they were delaying the U.S. mail. But his boss, Army chief of staff and WWI veteran Douglas MacArthur vetoed the plan. To resolve the issue, the veterans were escorted onto trucks and transported to the Indiana state line. Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Maryland each sent the veterans by truck on to the next state.

On May 25, 1932, the first veterans arrived. Waters and his men arrived on the 29th. Within a few weeks another 20,000 had joined them. They made camp wherever they could find space—in vacant lots and abandoned buildings. One large “Hooverville” sprang up along the Anacostia River, where veterans and their families erected crude structures from materials scavenged from an old dump at one end of the camp. The camp quickly became a local attraction. Washingtonians brought them much needed supplies, from sleeping bags to vegetables, to cigarettes, and often tossed coins to camp musicians. Soon the camp, named Camp Marks in honor of the police captain in whose precinct they were encamped, came to resemble a small city. There were named streets, a library, a post office, and a barber shop. Classes were set up for the children. They published their own newspaper, and staged vaudeville shows and boxing matches. Camp rules prohibited alcohol, weapons, fighting, and begging. And since the veterans wanted their motives to be unambiguous, communists were not allowed. Dozens of American flags could be seen waving above the shacks and mud. Marine Corps legend and retired Major General Smedley Butler turned out to praise and encourage them. It was the largest Hooverville in the nation.

Police Chief Pelham Glassford, himself a decorated WWI general, sympathized with his fellow vets. He toured the camp almost daily, organized medical care, provided building materials, solicited local merchants for food donations, and even contributed $773 out of his own pocket for provisions. Glassford once drove with Evalyn Walsh McLean, heiress to a Colorado mining fortune and owner of the famed Hope diamond, to an all-night diner where they ordered 1,000 sandwiches, 1,000 packs of cigarettes, and coffee. When McLean learned that the marchers needed a headquarters tent, she had one delivered along with books, radios and cots.

But Chief Glassford also knew that congress was not in a mood to pay bonuses. And Glassford also viewed the camp as symbolic of the vast army of the nation’s unemployed. He was wary of events getting out of hand, of creating widespread social disorder across the nation. Despite the camp rules, a few of the veterans apparently did have some Communist sympathies, a not uncommon phenomenon in 1932, since it appeared to many that capitalism had failed. And the press did report on this small communist faction of veterans. Rumors about communist revolutionaries soon spread throughout the city, and deeply affected the highest levels of government. At the Justice Department, J. Edgar Hoover’s Bureau of Investigation labored to find evidence that the Bonus Army had communist roots, evidence that never existed.

President Hoover’s press secretary, Theodore Joslin, wrote in his diary that “The marchers have rapidly turned from bonus seekers to communists or bums.” Government authorities also noted the absence of Jim Crow in this Southern event. They chose to interpret this racial camaraderie between former brothers-in-arms as symptomatic of left-wing radicalism. For several years, as the Great Depression had settled in, the government had been fearful of the possibility of an armed insurrection against Washington. Even before the arrival of the Bonus Army, the army had developed a plan to defend the city with tanks, machine guns, and poison gas.

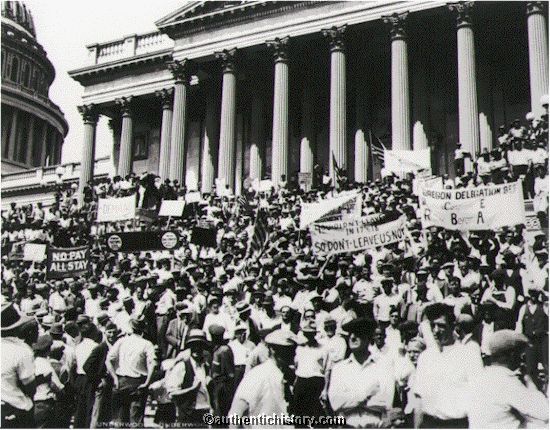

Within days of his arrival, Walter Waters had a full-blown lobbying operation under way. On June 4, the B.E.F. marched in full force down the streets of Washington. Veterans filled their representative’s waiting rooms, while others gathered outside the Capitol building. On June 14, the bonus bill, opposed by Republicans loyal to President Hoover, came to the floor. When Congressman Edward E. Eslick (D-TN) was speaking in support of the bill, he suddenly fell dead from of a heart attack. Thousands of Bonus Army veterans marched in his funeral procession, while congress adjourned out of respect. The following day, June 15, the House of Representatives passed the bonus bill by a vote of 211 to 176.

On the 17th, about 8,000 veterans gathered at the Capitol, feeling confident that the Senate would pass the bill. Another 10,000 were stranded behind the Anacostia drawbridge, which police had raised to keep them out of the city. Debate continued into the evening. Finally, around 9:30, Senate aides summoned Waters inside. He returned moments later to break the news to the crowd: the bill had been defeated. For a moment it looked as if the veterans would attack the Capitol. Instead, at the suggestion of a reporter, Waters asked the veterans to sing “America”. When the song was over, they slowly filed back to camp.

In the days that followed, many bonus marchers went home. But Waters and 20,000 others declared their intention “to stay here until 1945 if necessary to get our bonus.” They continued to demonstrate. On July 13, 1932, Police Chief Glassford addressed a rally on the Capitol grounds. He asked the veterans to raise their hands if they had served in France and were 100 percent American. As the weeks passed, conditions at the camp worsened. Evalyn Walsh McLean contacted Vice President Charles Curtis, who had attended dinner parties at her mansion. “Unless something is done for these men, there is bound to be a lot of trouble,” she told him. McLean’s efforts backfired. Vice President Curtis became paranoid when he saw veterans near his Capitol Hill office on the anniversary of the day the mobs stormed France’s Bastille. President Hoover, Army Chief of Staff MacArthur, and Secretary of War Patrick J. Hurley, increasingly feared that the Bonus Army would turn violent and trigger uprisings in Washington and elsewhere. Hoover was especially troubled by the veterans who occupied abandoned buildings downtown.

On July 28, on President Hoover’s orders, Police Chief Glassford arrived with 100 policemen to evict them. Waters informed Glassford that the men had voted to remain. Just after noon, a small contingent of vets confronted a phalanx of policemen near the armory, resulting in a quick, but violent skirmish. Veterans threw bricks while policemen used their nightsticks. Shortly after 1:45 p.m. another fight broke out in a building adjacent to the armory. Shots rang out. When it ended, one veteran lay dead, another mortally wounded. Three policemen were injured.

At this point, Army Chief of Staff General MacArthur had had enough. He decided to put their practiced plan into action, and assumed personal command. For the first time in the nation’s history, tanks rolled through the streets of the capital. MacArthur ordered his men to clear the estimated 8,000 veterans from the downtown area, and spectators who had been drawn to the scene by radio reports. Fred Blacher was 16 years old and standing on a corner waiting for a trolley. “By God, all of a sudden I see these cavalrymen come up the avenue and then swinging down to The Mall. I thought it was a parade,” Blacher later said. “I asked a gentleman standing there, I said, do you know what’s going on? What holiday is this? He says, ‘It’s no parade, bud.’ He says, ‘the Army is coming in to wipe out all these bonus people down here.'”Nearly 200 mounted cavalry, sabers drawn and pennants flying, rode out of the Ellipse, led by Major George S. Patton. They were followed by five tanks and about 300 helmeted infantrymen, armed with loaded rifles with fixed bayonets. The cavalry drove them all off the streets–pedestrians—curious onlookers, government workers and Bonus Army vets, including their wives and children. Soldiers with gas masks released hundreds of tear gas grenades at the crowd, setting off dozens of fires among the veterans’ shelter erected near the armory.

Naaman Seigle, 7 years old that day, happened to go downtown to a hardware store with his father. As they emerged from the shop, they saw the tanks and were hit with a dose of tear gas. “I was coughing like hell. So was my father,” Seigle recalled.

16-year-old Fred Blancher later said, “These guys got in there and they start waving their sabers, chasing these veterans out, and they start shooting tear gas. There was just so much noise and confusion, hollering and there was smoke and haze. People couldn’t breathe.”

By evening, the army arrived at Camp Marks. There, General MacArthur gave them twenty minutes to evacuate the women and children. The troops then attacked the camp with tear gas and fixed bayonets. One baby died, allegedly from tear-gas inhalation. They drove off the veterans and set fire to the camp,which quickly burned. The sky turned red in the dusk and the fire could be seen from all over Washington. Thousands of veterans and their families began a slow walk toward the Maryland state line, four miles away, where National Guard trucks waited to drive them to the Pennsylvania border.

Eyewitnesses, including MacArthur’s aide Dwight D. Eisenhower (later Supreme Allied Commander of WWII and two-term President of the United States), insisted that Secretary of War Hurley, speaking for the president, had forbade any troops to cross the bridge into Anacostia and that at least two high-ranking officers were dispatched by Hurley to convey these orders to MacArthur. Eisenhower later wrote in his book, At Ease, that MacArthur, “said he was too busy and did not want either himself or his staff bothered by people coming down and pretending to bring orders.” Eisenhower put it more bluntly during an interview with the late historian Stephen Ambrose. “I told that dumb son-of-a-bitch he had no business going down there,” he said.

Around 11:00 p.m., MacArthur called a press conference to justify his actions. “Had the President not acted today, had he permitted this thing to go on for twenty-four hours more, he would have been faced with a grave situation which would have caused a real battle,” MacArthur told reporters. “Had he let it go on another week, I believe the institutions of our Government would have been severely threatened.”

Over the next few days, newspapers and newsreels (shown in movie theaters) showed graphic images of violence perpetrated on once uniformed soldiers (and their families), those who had won the First World War, by uniformed servicemen. In movie theaters across America, the Army was booed and MacArthur jeered. The incident only further weakened President Hoover’s chances at re-election, then only three months away. Franklin, D. Roosevelt won easily.

For each of the next four years, veterans returned to Washington, D.C., to push for a bonus. Many of the men were sent to rehabilitation camps in the Florida keys. On September 2, 1935, several hundred of them were killed in a hurricane. The government attempted to suppress the news, but the writer Ernest Hemingway was aboard one of the first rescue boats, and he wrote an angry piece about it. Resistance to the bonus withered. Finally, in 1936, the veterans received their bonus.

Cite This Article

"Hoover & the Depression: The Bonus Army" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

April 20, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/hoover-depression-bonus-army>

More Citation Information.