The Bay of Pigs Invasion: Why It Failed

(See Main Article: The Bay of Pigs Invasion: Why It Failed)

The following article on the Bay of Pigs Invasion is an excerpt from Warren Kozak’s Curtis LeMay: Strategist and Tactician. It is available for order now from Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

In March, just two months into the Kennedy administration, Air Force Chief Curtis LeMay was called into a meeting at the Pentagon with the Joint Chiefs. He would represent the Air Force because White was out of town. LeMay noticed that there was something odd about the meeting right from the start. To begin with, there was a civilian in the room who pushed aside a curtain to reveal landing areas for a military engagement on the coast of Cuba. LeMay had been told absolutely nothing about the operation until that moment. All eyes turned to him when the civilian, who worked for the CIA, asked which of the three sites would provide the best landing area for planes.

LeMay explained that he was completely in the dark and needed more information before he would hazard a guess. He asked how many troops would be involved in the landing. The answer, that there would be 700, dumbfounded him. There was no way, he told them, that an operation would succeed with so few troops. The briefer cut him short. “That doesn’t concern you,” he told LeMay.

Over the next month, LeMay tried unsuccessfully to get information about the impending invasion. Then on April 16 he stood in for White—again out of town—at another meeting. Just one day before the planned invasion, he finally learned some of the basics of the plan. The operation, which would become known as the Bay of Pigs Invasion, had been conceived during the Eisenhower administration by the CIA as a way to depose Cuban dictator Fidel Castro. Cuban exiles had been trained as an invasion force by the CIA and former U.S. military personnel. The exiles would land in Cuba with the aid of old World War II bombers with Cuban markings and try to instigate a counterrevolution. It was an intricate plan that depended on every phase working perfectly.

The Bay Of Pigs Invasion: A Failure Of Military Strategy

LeMay saw immediately that the invasion force would need the air cover of U.S. planes, but the Secretary of State, Dean Rusk, under Kennedy’s order, had cancelled that the night before. LeMay saw the plan was destined to fail, and he wanted to express his concern to Defense Secretary Robert McNamara. But the Secretary of Defense was not present at the meeting.

Instead, LeMay was able to speak only to the Under Secretary of Defense, Roswell Gilpatric. LeMay did not mince words.

“You just cut the throats of everybody on the beach down there,” LeMay told Gilpatric.

“What do you mean?” Gilpatric asked.

LeMay explained that without air support, the landing forces were doomed. Gilpatric responded with a shrug.

The entire operation went against everything LeMay had learned in his thirty-three years of experience. In any military operation, especially one of this significance, a plan cannot depend on every step going right. Most steps do not go right and a great deal of padding must be built in to compensate for those unforeseen problems. It went back to the LeMay doctrine—hitting an enemy with everything you had at your disposal if you have already come to the conclusion that a military engagement is your only option. Use everything, so there is no chance of failure. Limited, half-hearted endeavors are doomed.

The Bay of Pigs invasion turned out to be a disaster for the Kennedy administration. Kennedy realized it too late. The Cubans did not rise up against Castro, and the small, CIA-trained army was quickly defeated by Castro’s forces. The men were either killed or taken prisoner. All of this made Kennedy look weak and inexperienced. A short time later, Kennedy went out to a golf course with his old friend, Charles Bartlett, a journalist. Bartlett remembered Kennedy driving golf balls far into a distant field with unusual anger and frustration, saying over and over, “I can’t believe they talked me into this.” The entire episode undermined the administration and set the stage for a difficult summit meeting between Kennedy and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev two months later. It also exacerbated the administration’s rocky relationship with the Joint Chiefs, who felt the military was unfairly blamed for the fiasco in Cuba.

This was not quite true. Kennedy put the blame squarely on the CIA and on himself for going along with the ill-conceived plan. One of his first steps following the debacle was to replace the CIA director, Allen Dulles, with John McCone. The incident forced Kennedy to grow in office. Although his relationship with the military did suffer, the problems between Kennedy and the Pentagon predated the Bay of Pigs Invasion. According to his chief aid and speechwriter, Ted Sorensen, Kennedy was unawed by Generals. “First, during his own military service, he found that military brass was not as wise and efficient as the brass on their uniform indicated . . . and when he was president with a great background in foreign affairs, he was not that impressed with the advice he received.”

LeMay and the other Chiefs sensed this and felt that Kennedy and the people under him simply ignored the military’s advice on the Bay of Pigs Invasion. LeMay was especially incensed when McNamara brought in a group of brilliant, young statisticians as an additional civilian buffer between the ranks of professional military advisers and the White House. They became known as the Defense Intellectuals. LeMay used the more derogatory term “Whiz Kids.” These were people who had either no military experience on the ground whatsoever or, at the most, two or three years in lower ranks.

In LeMay’s mind, this limited background could never match the combined experience that the Joint Chiefs brought to the table. These young men, who seemed to have the President’s ear, also exuded a sureness of their opinions that LeMay saw as arrogance. This ran against his personality—as LeMay approached almost everything in his life with a feeling of self-doubt, he was actually surprised when things worked out well. Here he saw the opposite—inexperienced people coming in absolutely sure of themselves and ultimately making the wrong decisions with terrible consequences.

What Was the Cuban Missile Crisis?

(See Main Article: What Was the Cuban Missile Crisis?)

The Cuban Missile Crisis was a very tense 13-day confrontation between the U.S. and the Soviet Union and is considered the closest the Cold War was to escalating in a full-scale war. What could have resulted in the deaths of over 100 million people on both the Russian and American sides, was resolved peacefully. This crisis is also known as the Caribbean Crisis and the Missile scare took place in October 1962 and was broadcasted on television all over the world.

Discovery of Missiles

After the U.S. tried to overthrow Fidel Castro’s rule in Cuba and failed in the Bay of Pigs invasion, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev made a secret deal with Castro to install Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba to foil any other American attempts to invade. During routine surveillance flights, U.S. intelligence however discovered the construction sites of these missiles and President Kennedy went public with the news. Instead of attacking Cuba, the Kennedy rule decided to rather place their navy and air force in such a way to “quarantine” the missile sites. In the 13 days that followed, negotiations took place in which neither country’s leader was willing to budge.

The Cuban Missile Crisis Was Horrifyingly Close to Becoming a Nuclear Holocaust

(See Main Article: The Cuban Missile Crisis Was Horrifyingly Close to Becoming a Nuclear Holocaust)

The Cuban Missile Crisis of the early 1960s nearly led to a full-scale nuclear war between America and the Soviet Union. It thankfully didn’t happen, but we came much closer than many realize.

Today’s guest Martin Sherwin is the author of the book Gambling with Armageddon. He gives us a riveting sometimes hour-by-hour explanation of the crisis itself but also explores the origins, scope, and consequences of the evolving place of nuclear weapons in the post-World War II world. Mining new sources and materials, and going far beyond the scope of earlier works on this critical face-off between the United States and the Soviet Union–triggered when Khrushchev began installing missiles in Cuba at Castro’s behest–Sherwin shows how this volatile event was an integral part of the wider Cold War and was a consequence of nuclear arms.

We look in particular at the original debate in the Truman Administration about using the Atomic Bomb; the way in which President Eisenhower relied on the threat of massive retaliation to project U.S. power in the early Cold War era; and how President Kennedy, though unprepared to deal with the Bay of Pigs debacle, came of age during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Here too is a clarifying picture of what was going on in Khrushchev’s Soviet Union.

Listen To The Whole Episode Here!

Result of the Cuban Missile Crisis

(See Main Article: Result of the Cuban Missile Crisis)

In the summer of 1962, negotiations on a treaty to ban above ground nuclear testing dominated the political world. The treaty involved seventeen countries, but the two main players were the United States and the Soviet Union. Throughout the 1950s, with the megaton load of nuclear bombs growing, nuclear fallout from tests had become a health hazard, and by the 1960s, it was enough to worry scientists. Kennedy, in particular, was pushing for a ban and was optimistic about succeeding.

It never happened. The result of the Cuban Missile Crisis was an increasing buildup of nuclear weapons that continued until the end of the Cold War.

Air Force General Curtis LeMay was less sanguine because the U.S. had already been limiting its above ground tests while the Soviets had been increasing their own. Just eight months earlier, on October 31, 1961, the Soviets tested the fifty megaton “Tsar” Bomb, the largest nuclear device to date ever exploded in the atmosphere (the test took place in the Novaya Zemlya archipelago in the far reaches of the Arctic Ocean and was originally designed as a 100 megaton bomb, but even the Soviets cut the yield in half because of their own fears of fallout reaching its population). LeMay did not see any military advantage for the U.S. to sign such a treaty. He doubted the countries would come to an agreement and felt vindicated when the talks deadlocked by the end of the summer. The agreement was ultimately signed the following spring, though, and remains one of the crowning achievements of the Kennedy Administration.

Completely unnoticed that summer was the sailing of Soviet cargo ships bound for Cuba. Shipping between Cuba and the USSR was not unusual since Cuba had quickly become a Soviet client state. With the U.S. embargo restricting Cuba’s trade, the Soviets were propping up the island with technical assistance, machinery, and grain, while Cuba reciprocated in a limited way with return shipments of sugar and produce. But these particular ships were part of a larger military endeavor that would bring the two powers to the most frightening standoff of the Cold War.

Sailing under false manifest, these cargo ships were secretly bringing Soviet-made, medium-range ballistic missiles to be deployed in Cuba. Once operational, these highly accurate missiles would be capable of striking as far north as Washington, D.C. An army of over 40,000 technicians sailed as well. Because the Soviets did not want their plan to be detected by American surveillance planes, the human cargo was forced to stay beneath the deck during the heat of the day. They were allowed to come topside only at night, and for a short time. The ocean crossing, which lasted over a month, was horrendous for the Soviet advisers.

The first unmistakable evidence of the Soviet missiles came from a U-2 reconnaissance flight over the island on October 14, 1962, that showed the first of twenty-four launching pads being constructed to accommodate forty-two R-12 medium-range missiles that had the potential to deliver forty-five nuclear warheads almost anywhere in the eastern half of the United States.

Kennedy suddenly saw that he had been deceived by Krushchev and convened a war cabinet called ExCom (Executive Committee of the National Security Council), which included the Secretaries of State and Defense (Rusk and McNamara), as well as his closest advisers. At the Pentagon, the Joint Chiefs began planning for an immediate air assault, followed by a full invasion. Kennedy wanted everything done secretly. He had been caught short, but he did not want the Russians to know that he knew their plan until he had decided his own response and could announce it to the world.

Kennedy shared his decision to pursue negotiation and a naval blockade of Cuba while keeping the option of an all-out invasion on the table with the Joint Chiefs on Friday, October 19. The heads of the military, General Earle Wheeler of the Army, Admiral George Anderson of the Navy, General David Shoup of the Marines, and LeMay of the Air Force, along with the head of the Joint Chiefs, Maxwell Taylor, saw the blockade as ineffective and in danger of making the U.S. look weak. As Taylor told the president, “If we don’t respond here in Cuba, we think the credibility (of the U.S.) is sacrificed.”

Of all the Chiefs, Kennedy and his team saw LeMay as the most intractable. But that impression may have come from his demeanor, his candor, and perhaps his facial expressions since he was not the most belligerent of the Chiefs. Shoup was crude and angry at times. Admiral Anderson was equally vociferous and would have the worst run-in with civilian leadership when he told McNamara directly that he did not need the Defense Secretary’s advice on how to run a blockade. McNamara responded, “I don’t give a damn what John Paul Jones would have done, I want to know what you are going to do—now!” On his way out, McNamara told a deputy, “That’s the end of Anderson.” And in fact, Admiral Anderson became Ambassador Anderson to Portugal a short time later.

LeMay differed from Kennedy and McNamara on the basic concept of nuclear weapons. Back on Tinian, LeMay thought the use of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs, although certainly larger than all other weapons used, were really not all that different from other bombs. He based this on the fact that many more people were killed in his first incendiary raid on Tokyo five months earlier than with either atomic bomb. “The assumption seems to be that it is much more wicked to kill people with a nuclear bomb, than to kill people by busting their heads with rocks,” he wrote in his memoir. But McNamara and Kennedy realized that there was a world of difference between two bombs in the hands of one nation in 1945 and the growing arsenals of several nations in 1962.

Upon entering office and taking responsibility for the nuclear decision during the most dangerous period of the Cold War, Kennedy came to loathe the destructive possibilities of this type of warfare. McNamara would sway both ways during the Cuban Missile Crisis, making sure that the military option was always there and available, but also trying to help the President find a negotiated way out. His proportional response strategy that would come into play in Vietnam in the Johnson Administration three years later was born in the reality of the dangers that came out of the Cuban crisis. “LeMay would have invaded Cuba and had it out . . . but with nuclear weapons, you can’t have a limited war,” McNamara remembered. “It’s completely unacceptable . . . with even just a few nuclear weapons getting through . . . it’s crazy.”

What Did Martin Luther King Do?

(See Main Article: What Did Martin Luther King Do?)

Martin Luther King, Jr. was an activist and pastor who promoted and organized non-violent protests. He played a pivotal role in advancing civil rights in America and has won a Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts to fight racial inequality in a non-violent matter.

Short Biography of Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King, Jr.’s birth date is January 15, 1929. He was born in Atlanta, Georgia, and was known for being a very passionate civil-rights activist, who had a great impact on the relations between races in the U.S. in the 1950s. He played a great role in creating the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Acts In 1964, at age 35, King was the youngest man ever to have received the Nobel Peace Prize and he is often quoted for the “I Have a Dream” speech he delivered in 1963. His assassination on April 4, 1968, was an event that shocked the world.

The Apollo Program Had a Surprising Close Relationship With 1960s Counterculture

(See Main Article: The Apollo Program Had a Surprising Close Relationship With 1960s Counterculture)

The summer of 1969 saw astronauts land on the moon for the first time and hippie hordes descend on Woodstock for a legendary music festival. For today’s guest, Neil M. Maher, author of the book Apollo in the Age of Aquarius, the conjunction of these two era-defining events is not entirely coincidental. He argues that the celestial aspirations of NASA’s Apollo space program were tethered to terrestrial concerns, from the civil rights struggle and the antiwar movement to environmentalism, feminism, and the counterculture.

With its lavishly funded mandate to send a man to the moon, Apollo became a litmus test in the 1960s culture wars. Many people believed it would reinvigorate a country that had lost its way, while for others it represented a colossal waste of resources needed to solve pressing problems at home. Yet Maher also discovers synergies between the space program and political movements of the era. Photographs of “Whole Earth” as a bright blue marble heightened environmental awareness, while NASA’s space technology allowed scientists to track ecological changes globally. The space agency’s exclusively male personnel sparked feminist debates about opportunities for women. Activists pressured NASA to apply its technical know-how to ending the Vietnam War and helping African Americans by reducing energy costs in urban housing projects. Particularly during the 1970s, as public interest in NASA waned, the two sides became dependent on one another for political support.

Listen to the entire podcast episode here!

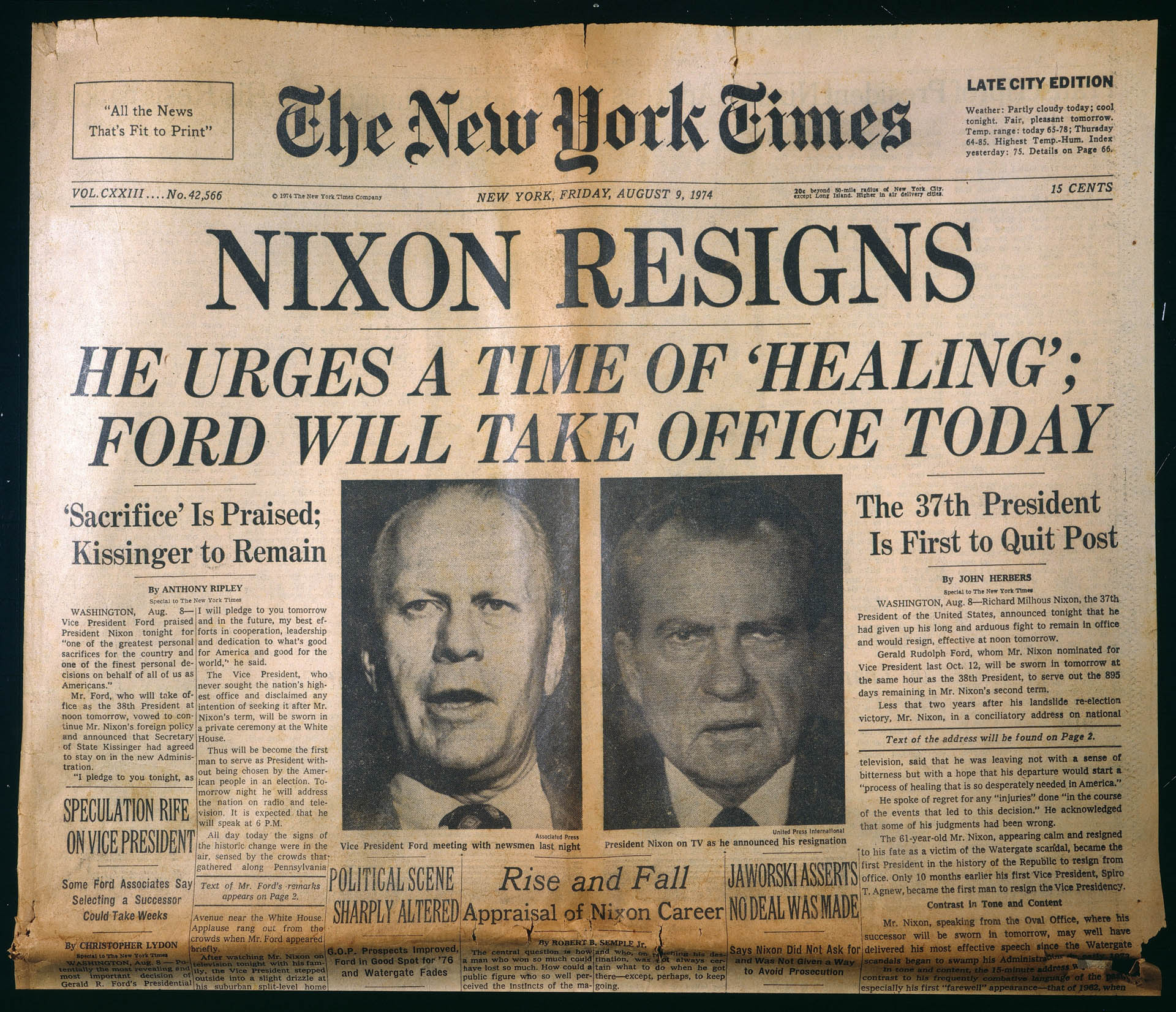

Watergate Scandal Timeline

(See Main Article: Watergate Scandal Timeline)

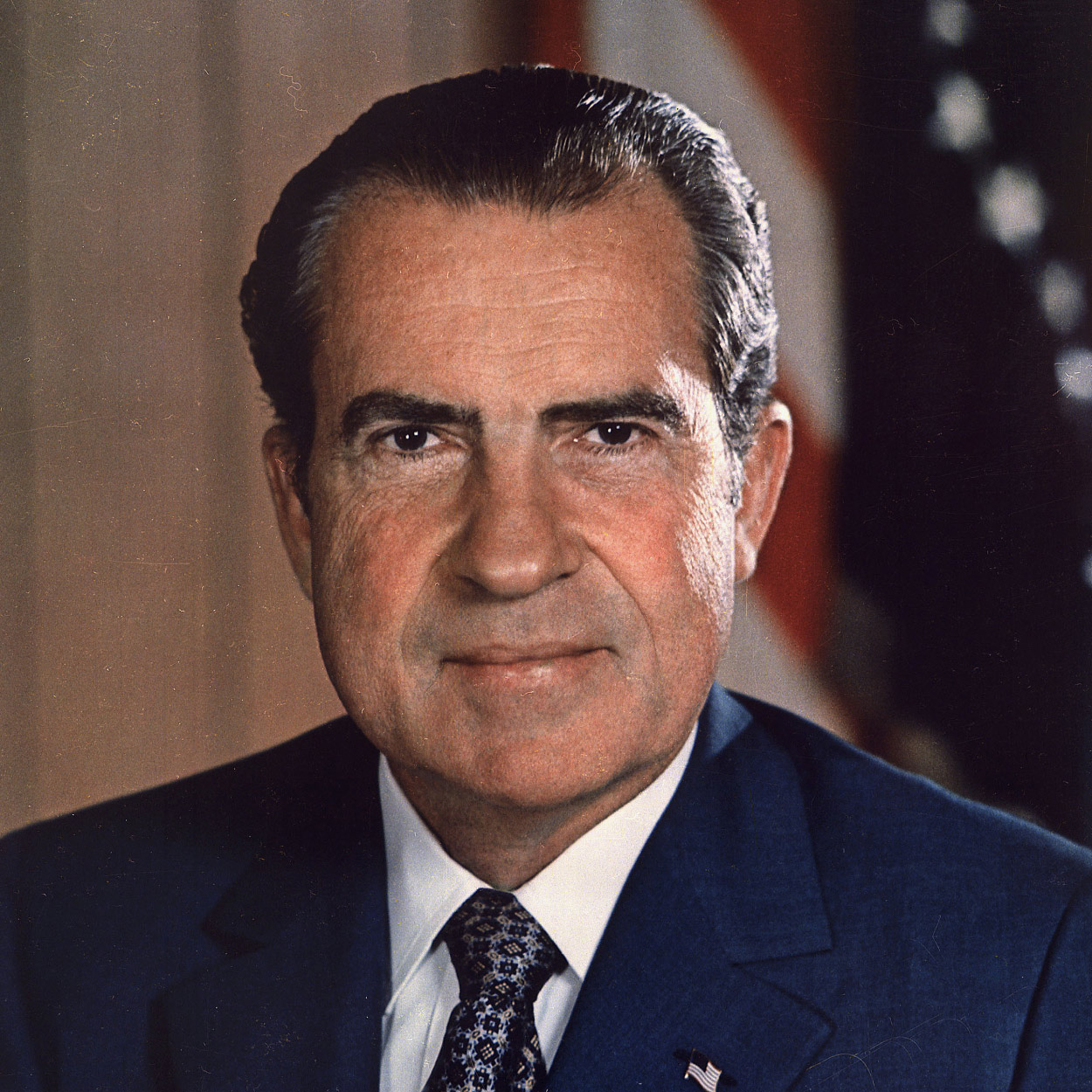

A Complicated President

There have been many scandals throughout American presidential history, but only one has ever brought down a presidency. To understand Watergate, it is helpful to have an understanding of the culture of the administration, and of the psyche of the man himself. Richard M. Nixon was a secretive man who did not tolerate criticism well, who engaged in numerous acts of duplicity, who kept lists of enemies, and who used the power of the presidency to seek petty acts of revenge on those enemies. As early as the 1968 campaign Nixon was scheming about Vietnam. Just as the Democrats were gaining in the polls following Johnson’s halting of the bombing of North Vietnam and news of a possible peace deal, Nixon set out to sabotage the Paris peace negotiations by privately assuring the South Vietnamese military rulers a better deal from him than they would get from Democratic candidate Hubert Humphrey. The South Vietnamese junta withdrew from the talks on the eve of the election, ending the peace initiative and helping Nixon to squeak out a marginal victory.

During Nixon’s first term he approved a secret bombing mission in Cambodia, without even consulting or informing congress, and he fought tooth and nail to prevent the New York Times from publishing the infamous Pentagon Papers (described below). Most striking, however, was Nixon’s strategy for how to deal with the enemies that he saw everywhere. Nixon sent Vice President Spiro Agnew on the circuit to blast the media, protestors, and intellectuals who criticized the Vietnam War and Nixon’s policies. Agnew spewed out alliterate insults such as “pusillanimous pussyfooters”, “nattering nabobs of negativism”, and “hopeless, hysterical hypochondriacs of history”. He once described a group of opponents as “an effete corps of impudent snobs who characterize themselves as intellectuals.”

The Washington “Plumbers”

But Nixon and his aides also discussed ways in which the President could use subterfuge to undermine his enemies and revenge perceived injustices. This became especially important to the President in 1972, when he was determined to win the election more comfortably than he had in 1968. Nixon had once approved the illegal break-in concept first floated by White House aide Tom Huston, even though Huston specifically told the president it was tantamount to burglary. However, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover refused to cooperate. (Hoover then died in May, 1972, and L. Patrick Gray was appointed acting director in his place). Nixon was especially infuriated by leaks in his administration, and none was bigger than that which became known as the Pentagon Papers, a sensitive Pentagon document that traced the often illicit history of America’s involvement in Vietnam. Nixon tried to block the publication of the document and lost. When Nixon discovered that military analyst Daniel Ellsberg had been the source of the leak, he told White House Counsel Charles Colson, “Do whatever has to be done to stop these leaks and prevent further unauthorized disclosures; I don’t want to be told why it can’t be done…I don’t want excuses; I want results. I want it done, whatever the cost.” Colson and yet another Nixon aide, John Ehrlichman, created a group whose task was to stop any further leaks. These White House Plumbers, as they came to be known, were tasked with finding a way to get revenge on Ellsberg. Two of the so-called plumbers were ex-CIA officer Howard Hunt, and ex-FBI agent G. Gordon Liddy. The plumbers tried to break into the office of Ellsberg’s psychiatrist in Los Angeles to get Ellsberg’s confidential treatment records, but the raid was completely botched. In addition to Hunt and Liddy, several other future Watergate burglars were part of this raid.

1972

The Watergate Break-In

June 16, 1972: In room 214 of the Watergate Hotel in Washington, D.C., seven men gathered to finalize their plans to break into the Democratic National Committee’s (DNC) headquarters, located on the sixth floor of one of the Watergate complex’s six buildings. One of these men, G. Gordon Liddy, was a former FBI agent. Another, E. Howard Hunt had retired from the CIA. James McCord would handle the bugging, Bernard Barker would photograph documents, and Virgilio Gonzalez would pick the locks. The remaining two, Eugenio Martinez and Frank Sturgis, would serve as lookouts. Several of these men were Cuban exiles who had met Hunt through their participation in the failed Bay of Pigs invasion back in 1961. Although the burglars would be caught in the act, many months would pass before enough details would emerge to create a picture of the events leading up to that night. These men had been hired by representatives of President Nixon’s administration to use illegal means to gather the information that could prove useful to Nixon winning the 1972 election.

On June 17, 1972, Frank Wills, a security guard at the Watergate Complex, noticed tape covering the latch on the locks of several stairway doors in the complex, allowing them to be closed without locking. He removed the tape, and thought nothing of it. An hour later, he discovered that someone (McCord) had re-taped the locks. Wills called the police, who showed up in plainclothes in an unmarked car, allowing them to pass by the lookout without the alarm being sounded. The burglars then turned off their radio when they heard a noise in an adjacent stairwell. The lookout saw several of the police officers outside on a terrace near the DNC offices, but when he alerted Liddy (Liddy and Hunt stayed in the hotel room, in two-way radio contact with the others), the ex-FBI agent was unable to reach them on the radio. Within minutes, the police arrested the 5 burglars. On their possession were wire-tapping equipment, two cameras, several dozen rolls of film, and a few thousand dollars in cash–$100 bills in sequential serial numbers (indicating the money had come directly from a bank, which could possibly be traced). Liddy and Hunt quickly vacated the premises, but the burglars also had two hotel room keys, one of which was for the room where Liddy and Hunt had stayed.

The five burglars were processed at the police station, where several of them gave fake names. Hunt hired a lawyer to quickly bail the men out, but he underestimated their bail amount. G. Gordon Liddy went to his office and commenced a shredding operation to eliminate any evidence of his involvement. Liddy worked for the Committee to Re-elect the President, sometimes referred to pejoratively as CREEP, and his involvement was a direct connection to President Nixon. McCord was the chief security officer at CREEP. Liddy and Hunt had also worked at the White House, which made the Nixon connection more serious. Meanwhile, a simple fingerprint check revealed the burglar’s true identities.

On Monday, June 19, 1972: The Washington Post reported, “One of the five men arrested early Saturday in the attempt to bug the Democratic National Committee headquarters is the salaried security coordinator for President Nixon’s re-election committee.” Shortly thereafter, it was revealed that a search warrant had been executed for the hotel rooms for which the burglars had keys, and that inside one of them were address books that listed Howard Hunt’s name or initials and included the hand-written notation, “WH,” for White House. The official reaction was swift. From the White House, Nixon’s Press Secretary, Ron Zeigler, dismissed the incident as some sort of petty thievery attempt. John Mitchell, the head of CREEP, denied that the organization had any connection to the event. These public denials were lies. In fact, an elaborate cover-up was already underway. The charge that would stem from the cover-up, “obstruction of justice,” would eventually bring Nixon down.

The Connection to the Committee to Re-Elect the President (CREEP)

On August 1, 1972, a $25,000 cashier’s check earmarked for the Nixon re-election campaign was found in the bank account of one of the Watergate burglars. Further investigation revealed that, in the months leading up to their arrests, more thousands had passed through their bank and credit card accounts, supporting the burglars’ travel, living expenses, and purchase. Several donations (totaling $89,000) were made by individuals who thought they were making private donations to the President’s re-election committee. The donations were made in the form of cashiers, certified, and personal checks, and all were made payable only to the Committee to Re-Elect the President. However, through a complicated fiduciary set-up, the money actually went into an account owned by a Miami company run by Watergate burglar Bernard Barker. On the backs of these checks was the official endorsement by the person who had the authority to do so, Committee Bookkeeper and Treasurer, Hugh Sloan. Thus a direct connection between the Watergate break-in and the Committee to Re-Elect the President had been established. When confronted and faced with the potential charge of federal bank fraud, Sloan revealed that he had given the checks to G. Gordon Liddy at the direction of Committee Deputy Director Jeb Magruder and Finance Director Maurice Stans. Liddy had then given the endorsed checks to Watergate burglar Bernard Barker, who then deposited the money in accounts located outside the U.S. and withdrew the money in the form of cashier’s checks and money orders in April and May. They did not know that banks kept records of these transactions.

Woodward, Bernstein & “Deep Throat”

Media coverage during 1972 was influential in keeping the Watergate story in the news, and in establishing the connection between the burglary and the Committee to Re-Elect the President. The most notable coverage came from Time, The New York Times, and especially from The Washington Post. Opinions vary, but the publicity these media outlets gave to Watergate likely resulted in more consequential political repercussions from the Congressional investigation. Most famous is the story of how Washington Post Reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein relied heavily on anonymous sources to reveal that knowledge of the break-in and subsequent attempt to cover it up had connections deep in the Justice Department, the FBI, the CIA, and even the White House.

Woodward and Bernstein’s most famous source was an individual they had nicknamed Deep Throat, a reference to a controversial pornography film of the time. Woodward claimed in his 1974 book, All The President’s Men, that the two would meet secretly at an underground parking garage just over the Key Bridge in Rosslyn, usually at 2:00 am, where Deep Throat helped him make the connections. Throughout the protracted investigation, Woodward would signal his source that he desired a meeting by placing a flowerpot with a red flag on the balcony of his apartment. If Deep Throat wanted a meeting, he would make special marks on page twenty of Woodward’s copy of The New York Times. The first meeting took place on June 20, 1972, only 3 days after the break-in. The identity of Deep Throat was the subject of intense speculation for more than 30 years before he was revealed to be the FBI’s #2, Mark Felt.

On September 15, 1972, Hunt, Liddy, and the 5 Watergate burglars were indicted by a federal grand jury.

On September 29, it was revealed that Attorney General & Nixon campaign chairman John Mitchell had controlled a secret Republican fund used to pay for spying on the Democrats. On October 10, the FBI reported that the break-in at the Watergate was part of a massive campaign of political spying and sabotage on behalf of the officials and heads of the Nixon re-election campaign. Despite these revelations, Nixon’s re-election was never seriously jeopardized, and on November 7 the President was re-elected in one of the biggest landslides ever in American political history.

1973

Watergate Burglars’ Trial Begins

On January 8, 1973, the five burglars plead guilty as their trial began. On January 30, just ten days after Richard Nixon’s second inauguration, Liddy and McCord were convicted on charges conspiracy, burglary, and wiretapping. Nixon had dodged a bullet in the months between the break-in and his re-election, but the Watergate Scandal did not die out after the burglars were tried.

White House Linked to Cover-Up

On February 28, 1973, Acting FBI Director L. Patrick Gray testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee regarding his nomination to replace J. Edgar Hoover. Committee chairman Sam Ervin, referencing newspaper articles, questioned Gray as to how the White House had gained access to FBI files related to the Watergate investigation. Gray stated he had given reports to White House counsel John Dean, that Dean had ordered him to give the White House daily updates on the FBI’s investigation, that he had discussed the investigation with Dean on many occasions, and that Dean had “probably lied” to FBI investigators about his role in the scandal. Subsequently, Gray was ordered not to talk about Watergate by Attorney General Richard G. Kleindienst. Gray’s nomination failed, and now White House counsel Dean was directly linked to the Watergate cover-up.

On March 19, 1973, convicted Watergate burglar and ex-CIA agent James McCord, still facing sentencing, wrote a letter to U.S. District Judge John Sirica. In the letter, McCord stated that he had been pressured to plead guilty and remain silent, that he had perjured himself during the trial, that the break-in was not a CIA operation, and that other, as yet unnamed government officials, were involved. Judge Sirica urged McCord to cooperate fully with the Senate Watergate Committee, which was about to begin its investigation. On March 23, as the burglars were sentenced, Dean hired an attorney and began to quietly cooperate with Watergate investigators. He did this without informing the President and continued to work as Nixon’s Chief White House Counsel, a clear conflict of interest.

Senate Watergate Committee Begins Investigation

On March 25, 1973, Senate Watergate Committee lawyer Sam Dash told reporters that he had interviewed James McCord twice, and that McCord had “named names” and had begun “supplying a full and honest account” of the Watergate operation. Dash refused to give details but promised that McCord would soon testify in public Senate hearings. Shortly after Dash’s press conference, the Los Angeles Times reported that two that McCord had named were White House Counsel John Dean, and Nixon campaign deputy director Jeb Magruder. The White House denied Dean’s involvement but said nothing about Magruder. Republican sources on Capitol Hill ominously confirmed the story, with one stating that McCord’s allegations were “convincing”. When Dean’s lawyer learned of a follow-up story planned by the Washington Post, he threatened to sue the newspaper if they ran the story. The Post printed the story anyway, along with the threat from Dean’s lawyer.

On March 28, 1973, James McCord testified before the Senate Watergate Committee in a closed 5-hour session. There were so many leaks to the press that committee leaders decided to conduct all future hearings in public sessions. The most significant leak was that fellow Watergate burglar G. Gordon Liddy had told McCord that the burglary and surveillance operation was approved by then-Nixon campaign chairman & Attorney General John Mitchell in February 1972 and that White House Special Counsel to President Charles Colson knew about the Watergate operation in advance (Colson had just quit his post to return to private practice). The next day, Colson told a National Press Club audience “I had no involvement or no knowledge of the Watergate, direct or indirect.”On April 8, 1973, White House Counsel John Dean told White House Chief of Staff H.R. Haldeman that he planned to testify before the Senate Committee. Haldeman advised against it, saying, “Once the toothpaste is out of the tube, it’s going to be very hard to get it back in.” Dean compiled a list of 15 names, mostly lawyers, who could be indicted in the scandal and showed then showed the list to White House counsel and Assistant to the President for Domestic Affairs, John Ehrlichman.

Busing and School Desegregation in the 1970s

(See Main Article: Busing and School Desegregation in the 1970s)

Families who had scrimped and saved to buy housing in what seemed to them orderly, clean, safe neighborhoods naturally looked with great dismay at the prospect of having their children bused to schools on the other side of town in neighborhoods that not even their own residents celebrated. And then, too, parents took for granted that they had choices about their children’s education. . . . As a result of desegregation suits, basic decisions about how the schools operated were removed from officials responsive to majority opinion and put in the hands of just one person, a federal judge who was politically protected by lifetime tenure and had no educational expertise.

It is hard to imagine how forced busing, particularly when undertaken in the manner of U.S. District Court Judge W. Arthur Garrity, Jr., in Boston, could not have resulted in increased racial tension and animosity. In 1974, in response to a suit brought by the NAACP, Judge Garrity decided upon a massive citywide busing plan to bring about greater racial mixture in the schools. One of the most controversial and ill-considered aspects of the plan involved a student exchange between Roxbury High, deep within the ghetto, and South Boston High, whose mainly working-class white students belonged to what has been described as “Boston’s most insular Irish Catholic neighborhood.” The entire junior class of South Boston High would be bused to Roxbury High, and half of South Boston’s sophomore class would be composed of students from Roxbury.

Busing as a means of achieving desegregation in schools was a policy that was popular in theory, but in practice was overwhelmingly opposed by the vast majority of white parents, and supported by only a slim majority of black parents. (And black parents often changed their minds after their experiences with busing.)

The policy’s opponents undoubtedly understood that such forced mixture would increase racial animosity, not alleviate it. They also recognized that sending one’s children to the local school was what encouraged community spirit, local patriotism, and civic virtue, and that tearing children away from their familiar surroundings in order to bus them hours each way to a school chosen for them by an education bureaucrat was morally wrong. As Professors Stephan and Abigail Thernstrom explain, parents wanted their kids, especially the youngest ones, in schools close by.

Busing Desegregation

Families who had scrimped and saved to buy housing in what seemed to them orderly, clean, safe neighborhoods naturally looked with great dismay at the prospect of having their children bused to schools on the other side of town in neighborhoods that not even their own residents celebrated. And then, too, parents took for granted that they had choices about their children’s education. . . . As a result of desegregation suits, basic decisions about how the schools operated were removed from officials responsive to majority opinion and put in the hands of just one person, a federal judge who was politically protected by lifetime tenure and had no educational expertise.

It is hard to imagine how forced busing, particularly when undertaken in the manner of U.S. District Court Judge W. Arthur Garrity, Jr., in Boston, could not have resulted in increased racial tension and animosity. In 1974, in response to a suit brought by the NAACP, Judge Garrity decided upon a massive citywide busing plan to bring about greater racial mixture in the schools. One of the most controversial and ill-considered aspects of the plan involved a student exchange between Roxbury High, deep within the ghetto, and South Boston High, whose mainly working-class white students belonged to what has been described as “Boston’s most insular Irish Catholic neighborhood.” The entire junior class of South Boston High would be bused to Roxbury High, and half of South Boston’s sophomore class would be composed of students from Roxbury.

Middle East Wars: 1975-2007

(See Main Article: Middle East Wars: 1975-2007)

Overview of Middle East Wars

Americans and Israelis in particular in the decades since the dramatic Israeli victories in the 1967 Six-Day War have widely embraced the myth that Arabs can’t win wars. This attitude appears to have been shared by Vice President Dick Cheney, Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, and their handpicked advisors when they sent the U.S. armed forces sweeping into Iraq in March 2003 and thought they could redraw the political map of the country at will.

In fact, the military history of the twentieth century shows that not only can Arabs fight, but they can do so very well. The Arab Middle East was one of the last areas of the world to resist conquest and colonization by the great European powers. Britain and France got their hands on it only when the Ottoman Empire finally collapsed after a long, tough, bitter fight in late 1918. It should be noted that most of the soldiers who surrounded, trapped, and ultimately captured the Anglo-Indian army at Kut in 1915 were Arabs recruited by the Ottomans from within the region. And they were among the very first to drive out the British and French. By 1948 every major Arab nation except Algeria independent, and by 1958 every one of them had successfully ejected all British and French influence over their affairs. This was not the record of nations of cowards, incompetents, or defeatists. It is true that Israel has won all the major conventional military wars against its Arab neighbors, often against formidable odds. But the Israelis were almost always fighting for their survival. Mass conscript Arab armies were sent into wars far from home, like the luckless Egyptian armies Nasser sent into Yemen in the 1960s and those destroyed by the Israelis in 1948, 1956, and 1967.

But the performance of the Iraqi army against vastly numerically superior Iranian forces during the eight-year Iran-Iraq War was excellent. The Iraqis had brave and excellent field commanders—until Saddam Hussein, murderous and witless as ever, killed the best of them himself— and ordinary Iraqi soldiers fought long and bravely with great discipline. Most important of all, they won.

In conventional wars, whenever Arab soldiers have been equipped, trained, and armed to fight modern Western armies on anything like equal terms, especially in defense of their homeland, they have usually fought bravely and well. The Israeli troops who fought the Jordanian and Syrian armies in 1967 and the Syrians and Egyptians in 1973 have testified to the toughness of their opponents. It was true that U.S. forces quickly annihilated the Iraqi conventional forces in the 1991 and 2003 Gulf Wars. But that wasn’t because they were fighting Arabs. It was because weak, underdeveloped nations usually can’t stand up to major industrial states, let alone superpowers, in quick, straightforward campaigns.

But when it came to guerrilla war, Muslim Arab nations proved to be some of the toughest foes in the world in the second half of the twentieth century. The National Liberation Front of Algeria proved far more ferocious and ruthless than even the Vietnamese in their eight-year war of independence against France from 1954 to 1962. The Israelis have yet to destroy Hezbollah, whose forces eventually drove them out of southern Lebanon. The mujahedin guerrillas in Afghanistan eventually drove out the Soviets after another eight-year war. And the Sunni Muslim guerrillas in central Iraq, at the present time, have yet to be operationally defeated or destroyed by U.S. and coalition forces. That is a pretty impressive record by anybody’s standards. Over the past sixty years, the nations of Continental Europe, Latin America, and sub-Saharan Africa cannot begin to compete with it.

The Ba’ath Party’s socialist roots

Even opponents of the Iraq War admit that Saddam Hussein was a brutal dictator, and his Ba’ath Party was a totalitarian oppressor. What you won’t find the Left admitting is this: Ba’athism has its source in the idealistic pipe dreams of elite, educated Marxists.

Throughout the past four decades, Syria and Iraq, the two great Arab nations of the Fertile Crescent, have been ruled by the Ba’ath Resurrection (Arab Socialist Party). Ba’ath rule brought endless economic stagnation, wars of foreign aggression, support for murderous terrorist organizations, apparently endless dictatorships, secret police tyrannies, massacres of tens of thousands of civilians in rebellious populations, and thousands of hair-raising examples of sadistic torture in underground dungeons.

Yet the Ba’ath Party was founded by misty-eyed, romantic revolutionaries (one might even call them innocents) who foresaw nothing but a bright golden age of peace, prosperity, and understanding for the Arab world under their enlightened rule. Provided no one got in the way, of course. It was the story of the Young Turks and their Committee of Union and Progress all over again. Like the Young Turks, the idealists of the Ba’ath Party proved the wisdom of British political philosopher Sir Isaiah Berlin: every attempt to create a perfect utopia on earth is guaranteed to create hell on earth instead.

Two Damascus schoolteachers—Michel Aflaq, a Christian, and Salah ad-Din al-Bitar, a Muslim—co-founded the Ba’ath Party in 1940. They wanted to end hatred and distrust between Christians and Muslims. They wanted to create a single, unified Arab nation across the Middle East founded on peace and social justice. They wanted to abolish poverty. They were all in favor of freedom and democracy and, of course, all for socialism. They hated tyranny in every form—or thought they did. But far from uniting the Arab world, the Ba’ath movement shattered it.

Far from establishing freedom and democracy, it established the longest-lasting, most stable, and bloody tyrannies in modern Arab history. The contrast with King Abdullah and King Hussein in Jordan, or with King Abdulaziz and his successors in Saudi Arabia, could not be greater. Far from joining together, the two nations where Ba’ath parties took and held power—Syria, and Iraq—were the most bitter rivals and enemies for generations, each of them claiming to be the only heir and embodiment of true Ba’athism while the other was evil heresy. In the year 1984, two versions of Big Brother that George Orwell would have recognized only too well were alive and ruling in Damascus and Baghdad. They would stay there for decades to come.

Arab tyrants: Assad and Saddam

After its humiliating defeat at Israel’s hands in the 1947–1948 war, through 1970, Syria changed governments faster than a revolving door swing. There were at least twenty-five different governments in twenty-two years. The Syrian republic became a laughingstock throughout the Middle East, and its armed forces were a byword for passive incompetence.

The Syrian army played no role whatsoever in the 1956 Israeli-Egyptian Sinai war. In 1967, after their air force was destroyed on the ground in the first hours of the war, they sat passively until Israeli defense minister Moshe Dayan was able to amass overwhelming forces to take the Golan Heights from them. But in the thirty-eight years since 1970, the Syrian government has not fallen once. The only change in its leadership came in 2000, when tough old President Hafez Assad died in his bed at the age of sixty-nine after thirty years of uncontested supreme power. His surviving son Bashar took over immediately as president and not a whisper of dissent was heard against it.

Assad also left behind as his lasting legacy the toughest military force in the Arab world, one that had faced the Israeli army in full land combat more often and performed more effectively against it than any other. Assad’s achievement contrasts not only with Syria’s past, but also with the fate of his fellow and rival Ba’ath dictator, President Saddam Hussein, in neighboring Iraq.

Both men came to power at almost the same time. Assad seized power in Damascus in 1970, determined to erase the humiliation and shame his nation, its armed forces, and most of all his air force had suffered at Israel’s hands in the 1967 Six-Day War. In 1968 Saddam became the number- two man and real power behind the throne in the Second Ba’ath Republic led by President Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr.

Assad and Saddam were both merciless tyrants who routinely employed torture on an unprecedented scale. Both of them waged wars of aggression and conquest against their neighbors. And neither of them hesitated to slaughter many thousands of their own citizens whenever they felt it necessary or expedient to do so. Both of them looked to the Soviet Union for weapons and support, and both of them hated the state of Israel like poison. Ironically, through the 1980s, it was Saddam who was seen in American eyes (especially those of Reagan administration policymakers) as by far the more moderate of the two. Saddam was battling the Shiite Islamic fanatics of Ayatollah Khomeini’s Iran from sweeping across the Middle East. Assad, by contrast, was forging a long-term alliance between Syria and Iran.

American policymakers saw Syria, not Iraq, as directing and protecting the most dangerous terrorist forces in the region through the 1980s. In 1983, Shiite Hezbollah suicide bombers backed by both Iran and Syria killed more than 250 U.S. Marines and more than 60 French paratroopers as they slept in their barracks on the outskirts of Beirut. But it was Assad who died in his bed, with his son surviving to rule as his heir and his regime and formidable army securely in place.

Saddam, who had inherited a far larger and more populous nation with the second-largest oil reserves on earth and a far larger and more powerful army—the fourth largest in the world by 1990—squandered all those assets before dying on December 30, 2006, at the end of a hangman’s rope. Assad’s lasting success remains ignored or underrated by U.S. and Israeli policymakers to this day. But there are sobering lessons to be learned from why he succeeded where Saddam and Nasser did not. The fearsome Sphinx of Damascus was a study in contrasts. He commanded the Syrian air force in the worst defeat in its history, yet used that defeat as a springboard to power. He inherited an army regarded as a bad joke throughout its own region and within three years made it formidable. It remains so to this day.

Assad led an Arab nationalist regime, yet he slaughtered Islamic believers and fundamentalists more ruthlessly and on a far wider scale than Saddam ever dared to. He held power for thirty years through the use of torture and terror and he came from a tiny ethnic and religious sect traditionally distrusted by his nation’s overwhelmingly Sunni Muslim majority. Yet he appears to have enjoyed real support and respect, and his son has ruled relatively securely since his death. Assad was the most dangerous enemy the State of Israel had after the death of Gamal Abdel Nasser. Yet he forged a lasting bond of respect with one of Israel’s greatest leaders: Yitzhak Rabin, whom he never met in person. He championed the Palestinian cause passionately, but he hated and despised the man who was the living embodiment of that cause: Yasser Arafat.

The first secret of Hafez Assad’s success was that he ruled according to Niccolo Machiavelli, not James Madison. He would have regarded the second Bush administration’s obsession with creating instant full-scale Western representative democracy and freedom throughout the Middle East not only as threatening his own power, but as a contemptible joke for ignoring the power realities of the region, its history, and political and military realities.

In the late 1990s, future Bush administration policymakers and intellectuals, led by David Wurmser, Vice President Dick Cheney’s chief Middle East advisor, openly described nations like Iraq and Syria as “failed states,” ignoring the fact that they had been around as distinct national entities since the early 1920s. And Saddam in Iraq and Assad in Syria both solved the problems of chronic instability that had plagued both nations for the twenty years before either of them took power. Assad, heeding Machiavelli’s counsel, regarded being feared as vastly more important than being loved. But though he killed widely, he did not, as Saddam did, kill continually or indiscriminately. In Iraq the wives and even children of those who crossed Saddam, even by contradicting him or one of his murderous sons in a conversation, were tortured, raped, mutilated, and murdered. Assad did those things only to his enemies, although there were enough of them.

In 1982, Assad crushed a popular uprising on behalf of the Islamist Muslim Brotherhood in the western Syrian city of Hama by annihilating the entire city. Tanks and heavy artillery were sent in to pulverize the remains. When U.S. intelligence analysts compared before and after photographs of the city from surveillance satellites they could not believe their own eyes. The death toll of civilians is generally estimated at 20,000, and it may even have been much higher. Rifaat Assad, Hafez’s brother and longtime secret police chief, later claimed to U.S. journalist Thomas Friedman that the death toll was really 38,000. Not even Saddam ever authorized killing against his own people with such intensity. But where Saddam killed endlessly, and appears to have had a psychotic need to do it, Assad killed only when it clearly served his interests.

The domestic nature of the two regimes was very different. Saddam ran a grim, utterly totalitarian state that survivors of Josef Stalin’s 1930s terror would have recognized all too well. Every public utterance on anything had to be in total conformity with the decrees of the Great National Leader, otherwise the torture chamber, the firing squad, or the hangman beckoned. In Syria, by contrast, those who stayed out of politics and public discourse could expect to live their own lives and even modestly enjoy their own private property.

The foreign policies and patterns of aggression of the two regimes were very different. Assad craved to control Lebanon, as more ineffectual Syrian rulers before him had, just as Saddam was determined to reincorporate Kuwait as the nineteenth province of Iraq, as Iraqi nationalists before him had.

Both of them did it, but Saddam openly and brutally invaded Kuwait in July 1990 and brought the entire military might of the United States and its allies down on his head only six months later. Assad craftily encouraged dissent, civil war, and chaos in Lebanon before sending in his army—supposedly to restore order—in 1976. He was able to stay there for six years until the Israelis drove him out. Saddam was mercilessly invincible in Iraq for thirty-five years from the establishment of the second Ba’ath Republic in 1968, where he held the real power for eleven years before ousting the ineffectual figurehead al-Bakr. (He had Bakr murdered by being pumped full of insulin three years later.)

But Saddam knew nothing about the world outside Iraq, and he miscalculated catastrophically every time he provoked it. Assad never did. He retained the strong support of the Soviet Union and later Russia from beginning to end. The Sphinx of Damascus defied the United States and undermined its influence successfully for decades, then came to a kind of accommodation with Washington during the Clinton administration when he had to. He even hosted two U.S. presidents on visits: Richard Nixon and Bill Clinton. ‘Assad’s relations with Israel were extraordinary in their achievements and complexity. Within three years of taking power, he unleashed the Syrian army to take the Jewish state by surprise in the first hours of the Seven Days War.

The Israelis eventually turned the tide against overwhelming forces in the Golan fighting against Syria and drove back to within artillery range of Damascus when a cease-fire was finally imposed. But although the Israelis could probably have taken the Syrian capital and could certainly have leveled it had the war continued, they never succeeded in routing the Syrians or in surrounding them, as Ariel Sharon was able to do against the Egyptian Third Army on the west bank of the Suez Canal. As guerrilla attacks, especially from Hezbollah, grew in 1982 after the Israeli military conquest of southern Lebanon, Assad was able to win back through guerrilla war and diplomatic skill what he had lost in direct war.

By 1984 Israel was forced out of most of southern Lebanon except for a buffer region north of its border. Some sixteen years later, Israeli prime minister Ehud Barak pulled out of there too. Hezbollah was able to establish a state within a state in the southern part of the country, and Syrian military forces and intelligence organizations moved back in to dominate much of the country for almost the next quarter-century. Saddam, by contrast, had been unable to hang on to Kuwait for more than six months.

But even while he was supporting tough, ruthless, and firmly effective guerrilla forces fighting the Israelis as Syrian (and Iranian) proxies in southern Lebanon, Assad ran no risks with provoking them on the Golan Heights, where troops of both nations continued to face each other. In the twenty-five years from the signing of the Israeli-Syrian disengagement agreement in 1975 to Assad’s death in 2000, not a single Israeli or Syrian soldier died in any incident on the Golan front. The long peace lasted through the first seven years after his death, though there are now many indications it may not last for much longer.

Did Jimmy Carter Really Bring Peace To The Middle East?

In four short years, President Jimmy Carter taught the world and his presidential successors an unfailing formula to wreck the Middle East: focus obsessively on bringing peace between the Israelis and the Palestinians, as if God chose only you and your personal “experts” to do it, and force friendly governments to slit their own throats by installing full-scale American-style democracy immediately. It fails every time. Carter proved conclusively, as Britain’s Neville Chamberlain had forty years before him, that the road to hell is paved with good intentions. A personally decent, honorable, incorruptible evangelical Christian, he wanted nothing more or less than to bring eternal peace between the Children of Abraham, the Jews and the Arabs.

Thanks to Gerald Ford and Henry Kissinger, Carter came into office with an awful lot going for him. Even so, his bungling, rather than his skill, gave him his big breakthrough. In 1977, Carter wanted the Soviet Union to be the United States’ partner in running a Middle East peace conference or diplomatic initiative to settle the Israeli-Arab conflict. Egyptian president Anwar Sadat confronted the idea with understandable horror. He had risked his life and the future of his country to kick Nasser’s Soviet advisors out in 1971. The last thing he needed was some extraordinarily naïve U.S. president letting them come back, bound for revenge. So the man who had confounded all expectations by expelling the Soviets six years earlier announced that within days he was going to visit Jerusalem.

The move was astounding beyond imagination. Nothing like it had ever been seen in the history of the Middle East. Sadat was going to meet the (supposedly) most hard-line, ferocious, and implacable Israeli leader of them all: Menachem Begin, whose Likud bloc had finally won power in the 1977 general elections after he had endured six previous electoral defeats in a row as leader of the Herut and Gahal parties. Nor was Sadat just going to Tel Aviv, which would have been radical enough. He was going to Jerusalem, the city whose Islamic holy sites had been in Israeli hands for more than a decade, to the unending fury of the entire Arab and Muslim worlds.

Friends and enemies alike were stunned. General Mordechai Gur, the tough Israeli general who had led the forces that stormed the Old City in 1967, suspected a trap. Only Begin took the whole thing in stride. Thousands of reporters and television news teams flooded in from around the world. Bezeq, Israel’s justly reviled nationalized telephone company, which usually couldn’t install a simple phone in an apartment without a three-year delay, set up flawlessly working free global communications for all of them in less than a week. Sadat’s Jerusalem visit was the biggest thing of its kind since the Queen of Sheba had come to woo King Solomon. Sadat was less impressed. And there was certainly no love affair between Egypt and Israel to rival the famous biblical one. But they did share their hearts’ desire: peace between their two countries and, for Sadat, a demand that the entire demilitarized Sinai Peninsula be returned to Egypt.

What followed was more than fifteen months of long, exhausting, mean, and obsessive negotiations. Carter threw himself into the heart of them and obsessed over every detail. (Like Herbert Hoover, Carter, who personally planned the schedules for the White House tennis court, thrived on details, the more useless the better.) Eventually, it all came together at the 1978 Camp David peace conference, where Carter basically locked up the sovereign leaders of Israel and Egypt in what amounted to a luxury prison, with the Secret Service as their jailers, until they finally agreed on a peace treaty. The irony is that none of it was necessary, and that lasting peace between Israel and Egypt may well have been possible, on far more favorable terms for Israel, without it.

Sadat frankly refused to make peace without getting all of the Sinai back, but since Kissinger’s monumental Sinai II agreement in 1975, he had the reality of peace anyway. The eventual treaty hammered out at Camp David was made possible only with enormous annual payments of more than $4 billion from the American taxpayer to Israel and Egypt alike. Israel got a little more than Egypt in absolute terms, but as it had a much smaller population, vastly more in per capita terms. But by giving up the Sinai, Israel lost the strategic depth it would desperately need if it made any long-term agreement with the Palestinians. It also lost the territory it would ultimately need if it ever faced an implacable enemy determined to acquire nuclear weapons. The more Israel’s population was concentrated in the area of greater Tel Aviv, the more tempting it would be for any genocidal-minded maniac to wipe out the bulk of the population at a single stroke. By giving up the Sinai, Begin made that nightmare a lot easier to achieve.

Retaining much of Sinai would also have made it far easier to maintain control of the Gaza Strip. The Palestinians were adept, as the Viet Cong had been before them, in constructing endless arrays of tunnels to smuggle weapons into Gaza from Egypt when the Israeli-Egyptian border was right beside them. And in sharp contrast to Gaza and the West Bank, Sinai was almost uninhabited. Far from bringing peace with its neighbors, there is a good argument to be made that Carter’s work enabled Begin to start a disastrous war that his country has been paying for ever since. Peace with Egypt in the south freed Begin to launch his army into Lebanon to the north in spring 1982.

But Defense Minister Ariel Sharon’s grand design for Lebanon quickly went disastrously wrong. Israel suffered hundreds of dead and thousands of wounded before it finally withdrew from much of southern Lebanon after a broken Begin left office. Had Egypt remained essentially powerless and in the U.S. orbit, but without a final peace treaty with Israel, and had Israel maintained control of most of the Sinai, but forced to be on guard in the south, Begin would never have dared to open up an ambitious new front in the north.

He and Sharon might still have swept the PLO out of the large enclave it controlled in southern Lebanon, but they would never have dared to push on into the heart of Lebanon. Hezbollah, created by this series of maneuvers, proved a far more formidable and long-lasting enemy of the Jewish state than the PLO had ever been. The Israeli-Egyptian peace treaty also cost America the life of its most important and constructive ally in the entire Middle East. On October 6, 1981, Anwar Sadat proudly reviewed his armed forces as they marched past him in massed array. A small group of Islamic extremist conspirators in his own army, furious at Sadat’s peace with Israel, broke ranks as their unit marched by the reviewing stand and stormed it, their automatic rifles blazing. Sadat died instantly. His fate was sealed by the most enormous decoration he wore on his chest: the Star of Sinai. It was just too big and garish to miss.

Had the 1975 Sinai II disengagement agreement been allowed to define Israeli-Egyptian relations, Sadat would have lived and extreme Islamism would never have won its greatest assassination coup to date. But by then, the other supposed great ally of the United States in the Middle East had also fallen, even more a victim to Carter’s romantic and farcical sense of priorities. Carter’s “great achievement” of peace between Israel and Egypt came at a disastrous price: it resulted in Iran’s fall to Ayatollah Khomeini, launching a virulent new form of Islamist extremism hitherto inconceivable. From November 1977 through March 1979, Carter was so obsessed with achieving an Israeli-Egyptian peace treaty that he ignored the increasing evidence that the shah of Iran’s position was crumbling with amazing speed.

Clinton: Carter All Over Again

At first glance, Bill Clinton’s dealings with the Middle East appeared the absolute opposite of the hapless Carter’s experience. And compared with many of the bungles the subsequent Bush administration would make, it arguably still looks good.

Under Clinton, peace and relative stability were preserved throughout the region, and the Israeli-Palestinian peace process seemed to advance. Even Iran appeared to become more moderate, with the 1997 election of the remarkably moderate (at least by Islamic Republic standards) Mohammad Khatami. And oil prices until 1999 stayed astonishingly low. Compared to Carter’s nightmarish record of buffoonish incompetence, this was a welcome contrast indeed.

But as it turned out, Clinton repeated Carter’s basic mistake of focusing obsessively on the Israeli-Arab peace process. He shared Carter’s megalomaniacal delusion that he could forge the lasting peace that had eluded previous generations on either side. As a result, like Carter, Clinton and his top experts on the region ignored or catastrophically underrated the remorseless—but otherwise highly preventable—rise of a ferocious enemy that would kill more Americans in a single day than the Japanese navy did at Pearl Harbor. Clinton cannot take either credit or blame for the Oslo Peace Process. It was former Israeli super-hawk (now turned ultra-dove) Shimon Peres who laid that egg. And it was Rabin—haunted by memories of the death cries of his young comrades in the 1947 fighting for Jerusalem—who made the crucial decision to go along with Peres.

But once Rabin and Arafat held that famous meeting and shook hands on the White House lawn in 1993, Clinton and his team eagerly jumped aboard the “Peace at Last” express. Where Carter had obsessively thrown himself into every nook and cranny of the Israeli-Egyptian negotiations for eighteen months, Clinton did so for a full seven years. The climax came in July 2000 when, with the sands of time running out on his second term, Clinton convened a Camp David II peace summit with Israeli prime minister Ehud Barak and the old and ailing Arafat.

Using Jimmy Carter as a model for anything, even for what still appeared to be his one undisputed great diplomatic achievement, should have given the Clinton team pause, but clearly it did not. The idea and driving force for the conference reportedly came from Barak, who capped a brilliant career as Israel’s top special forces commander (during which his exploits exceeded even those of Dayan and Sharon) with a short and utterly bungled premiership. But there is no doubt that Clinton and his top peace negotiators were exceptionally eager to make the effort. For such an ambitious endeavor, Barak and his team bungled the staff work for Camp David II abysmally. It is difficult to imagine that the man who had been the legendary commander of special forces and then a respected IDF chief of staff could have proven so sloppy in preparing for his greatest challenge as national leader.

But Barak, as his intimates later revealed, did not even do the basic diplomatic preparation of sounding out the Palestinians’ absolute bottomline terms for a settlement. What he offered was, from the Israeli perspective, immensely generous: more than 90 percent of the West Bank. But he didn’t yield on the right of return for the descendents of Palestinian refugees from the 1947 war, about which Arafat was insistent. He also insisted on maintaining total Israeli control over the entire city of Jerusalem, and on retaining the relatively small amount of territory beyond the 1967 borders on which 180,000 Israelis had built towns and settlements. This was 80 percent of the total Israeli settler population beyond the Green Line.

Over the previous seven years, Arafat had gained a vast amount for himself, and had made his first gains for his long-suffering people, by compromising for the first time in his life. But at Camp David II, when he could have won so much more, he turned it down. Demanding nothing but the entire cake, he lost the much larger slice of it he would otherwise have had. His decision was true to the patterns of bizarre behavior and logic that had governed his entire life. It also condemned Israelis and Palestinians alike to a new round of war and suffering greater than anything they had endured in more than fifty years.

For Clinton, the failure of Camp David II dashed his dreams of securing a lasting and secure peace for both sides. But worse by far, Clinton and his chief Middle East peace envoy, Dennis Ross, had forgotten the lasting wisdom of Henry Kissinger: when disputes are not resolvable, it is best to recognize what cannot be resolved and simply concentrate on improving the conditions that can be improved. Eventually, conditions and attitudes may change sufficiently to reconcile the previously irreconcilable, but trying to do too much too soon always backfires.

That was the consequence of Camp David II. When Ariel Sharon visited the Temple Mount in September 2000, an admittedly potentially incendiary move, Arafat used it to set off a new Palestinian intifada. The First Intifada had been fought with violent but non-lethal protests, because guns and explosives were not easily available on the West Bank and in Gaza after twenty years of effective Israeli control. The Second Intifada was far more lethal. Some 1,100 Israeli civilians died in the following four years of mayhem, and probably at least three times that number of Palestinians died from Israeli retaliation. Rabin’s idealism and Peres’s utopian visions had born bitter fruit.

The United States bore a worse and more direct price. In the years before Camp David II, and in the fevered months up to, during, and after it, Clinton and his top officials paid no attention to the mounting evidence that al Qaeda, a once obscure but increasingly formidable extreme Islamist terrorist group led by Saudi renegade Osama bin Laden, had become emboldened. Encouraged by its previous impunity from retaliation by the U.S. armed forces, it was now preparing a terrorist attack of unprecedented scale on the two of the greatest cities in the United States.

More American History

(Click here for main page)

Below are the main categories of topics that you can find to learn more.

Cite This Article

"Kennedy, Watergate, and The Middle East" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

April 25, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/kennedy-watergate-middle-east>

More Citation Information.