The following article on Leonid Brezhnev is an excerpt from Lee Edwards and Elizabeth Edwards Spalding’s book A Brief History of the Cold War It is available to order now at Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

In October 1964, Leonid Brezhnev, the ultimate apparatchik, replaced the unpredictable Nikita Khrushchev as the general secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Stalinist members of the Politburo had never forgiven Khrushchev for his anti-Stalin speech at the Twentieth Party Congress, and an overly confident Khrushchev had failed to deliver on his promises to improve the Soviet economy. Brezhnev kept his promise to the Soviet military—when Lyndon Johnson left the White House in January 1969, Moscow was close to parity with the United States in land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles.

Emulating the Stalinist cult of personality,Leonid Brezhnev instituted a policy of calculated oppression. Rather than sending all dissidents to the Gulag (which still existed), the KGB of Leonid Brezhnev more often fired them from their jobs and expelled them from the Communist Party, rendering them powerless and destitute. It also began placing the more outspoken dissidents in psychiatric hospitals, where they were given electric shock treatment and mind-altering drugs.

One victim of this treatment was Vladimir Bukovsky, who was “diagnosed” with various mental illnesses because he had engaged in political dissent. Here is an excerpt from his bestselling memoir, To Build a Castle:

You are alone in the punishment cell, in the box. There, you get no paper, no pencil, and no books. . . . You get fed only every other day. . . . Blankets or warm clothes are forbidden. . . . Dried gobs of bloody saliva adorn the walls from the TB sufferers who have been incarcerated here before you. . . . At night you can doze off for only ten to fifteen minutes at a time before leaping up again and running in place . . . to get yourself warm. . . . Three times a day they bring you a drink of water. . . . Time comes to a halt. . . . Gradually the patches on the walls start to weave themselves into faces as if the entire cell were adorned with the portraits of prisoners who have been here before you—it is a picture gallery of all your predecessors.

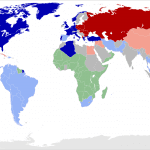

The Soviets also acted decisively to preserve communist solidarity in Eastern and Central Europe. In 1967, Alexander Dubcek, the new communist party leader of Czechoslovakia, decided to institute a Khrushchev-like thaw, the so-called “socialism with a human face.” Neither the Soviets nor the hard-liners in their satellites wanted any such experiment. Brezhnev considered a military solution as early as April 1968. Directed by the Kremlin, the armed forces of the Warsaw Pact, except for Romania, poured into Czechoslovakia in August, ending the “Prague Spring.” Dubcek was summarily removed from office and later forced to resign as first secretary of the Communist Party.

At a post-invasion meeting with Warsaw Pact leaders, Leonid Brezhnev boasted that victory in the Cold War was in sight—within two decades the United States would be beaten. And he proclaimed a new doctrine: each socialist country, and especially the Soviet Union, had a duty not only to preserve socialism at home but protect it abroad— by force if necessary. In fact, the Brezhnev Doctrine was not new but a corollary of the Leninist Doctrine that power once acquired is never relinquished, either internally or externally.

The embrace of Leonid Brezhnev of “peaceful coexistence” was cynical in the extreme. The Kremlin regarded peaceful coexistence as a strategy of avoiding outright war with the United States while making the world socialist. It was a strategy formulated by Lenin, who called peaceful coexistence “the (temporary) absence of armed hostilities” while awaiting the “inevitable” world revolution. By 1970, the term had been redefined as “the intensification of the international class struggle,” especially in the Third World. Even as he was signing the first Strategic Arms Limitations Treaty (SALT I) in 1972, Brezhnev told party leaders that “the world outlook and class aims of socialism and capitalism are opposite and irreconcilable.”

At a dinner for Fidel Castro in June 1972, Leonid Brezhnev drove home the point regarding the role of peaceful coexistence:

While pressing for the assertion of the principle of peaceful coexistence, we realize that successes in this important matter in no way signify the possibility of weakening our ideological struggle. On the contrary, we should be prepared for an intensification of this struggle and for its becoming an increasingly acute form of struggle between the two social systems.

Meanwhile, U.S. leaders from Richard Nixon to Gerald Ford to Jimmy Carter raised high the banner of “détente,” defined by them as a relaxation or reduction of tensions between Western and communist nations. The Soviets were happy to toast détente while communizing nations wherever they could. A weary America regarded détente as a way for each side to show restraint in its relations with the other, while the Soviet Union, ever aggressive, understood détente to be a continuing competitive relationship arising from ideological, economic, and strategic incompatibility.

This article is part of our larger collection of resources on the Cold War. For a comprehensive outline of the origins, key events, and conclusion of the Cold War, click here.

|

This article is an excerpt from Lee Edwards and Elizabeth Edwards Spalding’s book A Brief History of the Cold War. It is available to order now at Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

You can also buy the book by clicking on the buttons to the left.

Cite This Article

"Leonid Brezhnev — Pushing For Cold War Victory" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

April 19, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/leonid-brezhnev>

More Citation Information.