Artisans in Mesopotamia represented the middle class of society. They were free citizens with a few rights and privileges who created the goods desired by the upper classes. Fine pottery, gold and silver jewelry, carved ivory figurines, finely woven textiles and carved semi-precious gemstones were all goods traded throughout the cities of Mesopotamia and the greater world. Providing these goods were the work of a city’s craft workers or artisans.

The nobility and priesthood ruled Mesopotamian city-states, but the upper classes relied on those below them for trade goods and labor. As civilization developed with its greater societal complexity and enlarged populations, a class of people who weren’t required for agricultural work or for building projects arose. Craft workers produced the finished goods that brought wealth to the cities.

Along with the artisans, merchants and traders belonged in the middle class. Local traders ensured the distribution of subsistence goods such as salt, food items and fiber for making clothing. Long-distance traders took finished goods from the artisans and craft workers, such as weapons, tools, linen or wool cloth, jewelry, pots and cauldrons to other cities and regions where the goods would be sold or traded.

At times in Mesopotamia’s history, middle class workers were relatively strong and independent. At other times, the upper classes consolidated, their power and lower classes suffered. Still, as trade was vital to all Mesopotamian cities, craft workers and traders were respected members of society.

Craft workers could work in small private workshops limited to their extended family. They made goods that were utilitarian such as cauldrons, brooms, tableware and textiles for daily use. They also made fine works of art to be traded in the market or for kings, nobles and the priesthood. Many artisans worked exclusively for temples, which sometimes employed thousands of workers in dyeing, weaving and creating garments for the nobility and to clothe the gods in their temples. Temples ran craft workshops providing the means for artisans to make their goods such as pottery kilns, potters wheels, smithies and forges for metallurgy.

Craft knowledge was closely guarded and passed down from fathers to sons. Most craft workers had certain techniques, formulas or recipes they protected from the competition. Occasionally, a fine artisan would gain popularity and his or her works become known to the nobility, who then created more demand for the artisan’s products. Perfumers, musicians, jewelry-makers, scribes and poets might become the special favorite of the aristocracy.

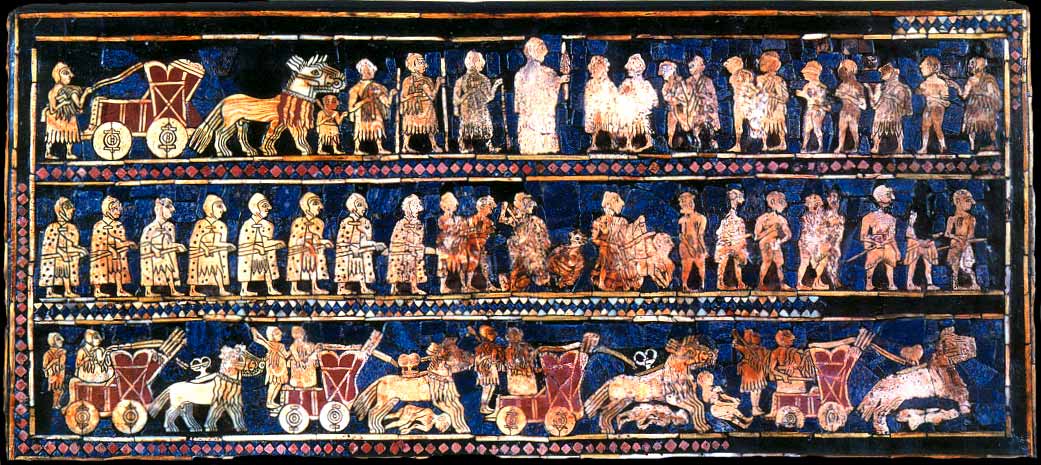

Usually, however, most craft workers worked in city neighborhoods in family workshops. They dealt with merchants and traders on a daily basis, both to obtain the raw materials of their craft and to sell their finished products. Their goods brought riches to the cities, playing an important role in the economy of ancient Mesopotamia. While cloth and wooden goods don’t survive the ravages of time, items crafted of metal, clay, ivory, stone or semi-precious gems remain to reveal the artistry of Mesopotamian craftsmen.

This article is part of our larger resource on Mesopotamian culture, society, economics, and warfare. Click here for our comprehensive article on ancient Mesopotamia.

Cite This Article

"Mesopotamian Artisans and Craft Workers" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

April 17, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/mesopotamian-artisans-and-craft-workers>

More Citation Information.