The following article on the Nixon Doctrine is an excerpt from Lee Edwards and Elizabeth Edwards Spalding’s book A Brief History of the Cold War It is available to order now at Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

Despite his Quaker roots, Nixon had a reputation as a staunch anticommunist. Campaigning for the presidency in the fall of 1968, Nixon said that the United States should “seek a negotiated end to the war” in Vietnam while insisting that “the right of self-determination of the South Vietnamese people” had to be respected by all nations, including North Vietnam. Pressed for details, Nixon said he had “a secret plan” that he would reveal after he was elected. It turned out to be “Vietnamization,” the turning over of the ground fighting to South Vietnamese forces, backed by U.S. air power. This plan was part of his broader theory that came to be known as the Nixon Doctrine.

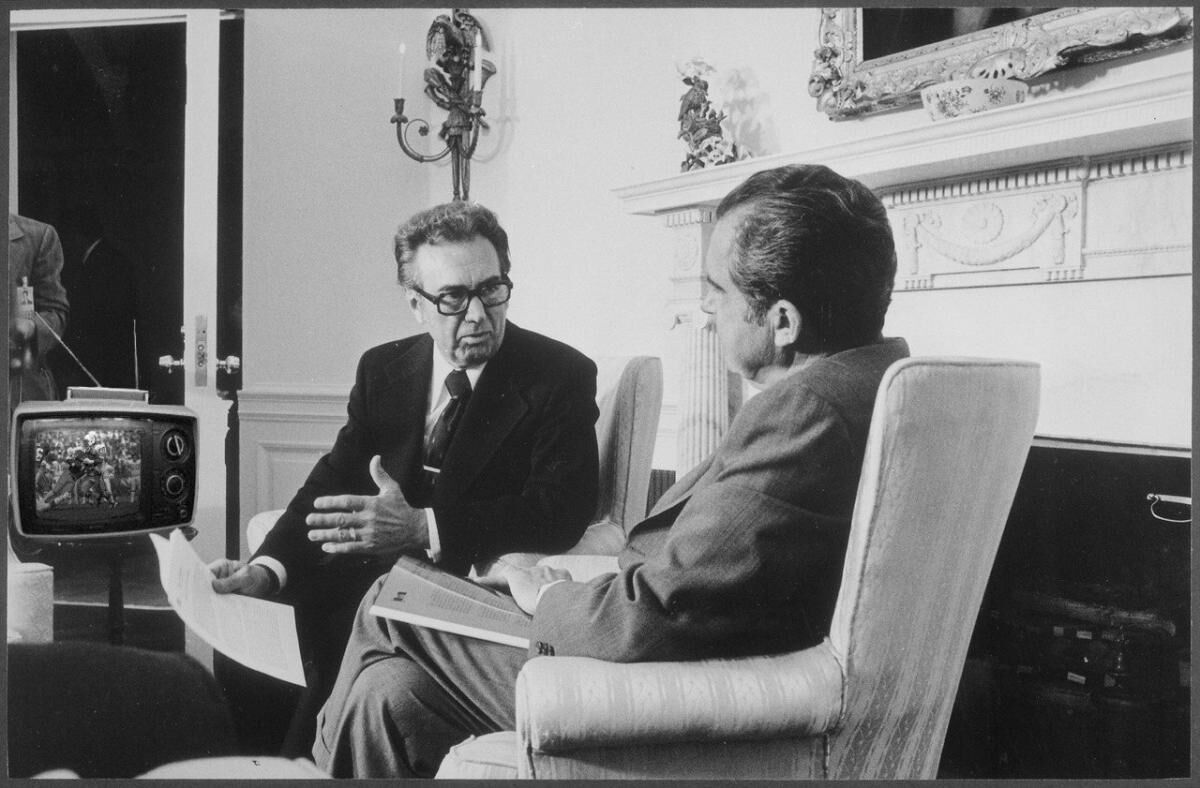

Nixon and Henry Kissinger (first as national security adviser and then secretary of state) agreed on the need to accept the world as it was—conflicted and competitive— and to make the most of it. It was in America’s interest, Kissinger said, to encourage a multipolar world and move toward a new world order based on “mutual restraint, coexistence, and ultimately cooperation.”

Containing communism was no longer U.S. policy, as it had been under the previous four administrations.

In a multipolar world—comprising the United States, the Soviet Union, China, Europe, and Japan—America could work even with communist countries as long as they promoted global stability, the new core of U.S. foreign policy.

The Nixon Doctrine contained three parts:

- The United States would honor existing treaty commitments;

- It would provide a nuclear shield to any ally or nation vital to U.S. security;

- It would furnish military and economic assistance but not manpower to a nation considered important but not vital to the national interest.

Gone was the Truman-Eisenhower-Kennedy understanding that a loss of freedom anywhere was a loss of freedom everywhere. As Kissinger put it, “Our interests shall shape our commitments rather than the other way around.”

Nixon was most lucid about the Nixon Doctrine in his June 1974 commencement speech at the U.S. Naval Academy. He suggested that U.S. foreign policy should be guided by a fusion of idealism and realism. But the president spent much of his speech on what he really thought was important: making his kind of realism the basis for American foreign policy in general and Cold War policy in particular. Because there were limits to what America could achieve and because U.S. actions might produce a slowdown or even reversal of détente, Nixon rejected the notion that the United States should aim to transform the internal behavior of other states.

“We would not welcome the intervention of other countries in our domestic affairs,” Nixon said, “and we cannot expect them to be cooperative when we seek to intervene directly in theirs.” At the same time, he emphasized that the goal of peace between nations with totally different systems was also a high moral objective. Nixon’s eye was on building and sustaining a relative peace and stability among the great powers in which the status of the United States could be preserved.

The Nixon Doctrine At Work in Vietnam

The Nixon-Kissinger foreign policy team went to work, beginning with Vietnam. In four years, the Nixon administration reduced American forces in Vietnam from 550,000 to twenty-four thousand. Spending dropped from twenty-five billion dollars a year to less than three billion. In 1972, the president abolished the draft, eliminating a primary issue of the anti-war protestors. At the same time, he kept up the American bombing in North Vietnam and added targets in Cambodia and Laos that were being used by Vietcong forces as sanctuaries, while seeking a negotiated end to the war.

An impatient Congress and public pressed the administration for swifter results and accurate accounts of the war. President Johnson and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara had been guilty of making egregiously false claims about gains and losses in Vietnam.

When North Vietnam continued to use Cambodia as a staging ground for forays into South Vietnam, Nixon approved a Cambodian incursion in May 1970 by U.S. and Vietnamese troops. Escalation of the war produced widespread student protests, including a tragic confrontation at Kent State University, where four students were killed by inexperienced members of the Ohio National Guard. On June 24, the Senate decisively repealed the 1964 Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which had first authorized the use of U.S. force in Vietnam. It later passed the Cooper-Church Amendment prohibiting the use of American ground troops in Laos or Cambodia.

The Nixon Doctrine as a Diplomatic Tool

But the Nixon Doctrine also contained elements of force. Nixon tried to exploit the open differences between the Soviet Union and Communist China, reflected in the armed clashes in March 1969 along the Sino-Soviet border. Nixon warned the Kremlin secretly that the United States would not take lightly any Soviet attack on China. He and Kissinger initiated secret negotiations with China that resulted in Nixon’s historic visit in February 1972. Mao Zedong and China’s premier, Zhou Enlai, led Nixon to believe they would encourage North Vietnam to end the conflict. Conservatives criticized Nixon’s unofficial “recognition” of Communist China because it weakened U.S. relations with the Republic of China on Taiwan, which functioned as a political alternative to the mainland and also served as a forward base for the U.S. military in Southeast Asia.

On January 22, 1973, in Paris, Secretary of State William Rogers and North Vietnam’s chief negotiator, Le Duc Tho, signed “An Agreement on Ending the War and Restoring Peace in Vietnam.” In announcing the ceasefire, Nixon said five times that it represented the “peace with honor” he had promised since the 1968 presidential campaign. But the United States accepted North Vietnam’s most crucial demand—that its troops be allowed to stay in the South—a concession that sealed the fate of South Vietnam. It hardly mattered that the United States could maintain aircraft carriers in South Vietnamese waters and use planes based in Taiwan and Thailand if Hanoi broke the accords. Airpower hadn’t won the war. It wouldn’t secure the peace.

The North Vietnamese began violating the peace treaty as soon as it was signed, moving men and equipment into South Vietnam to rebuild their almost decimated forces. In response, the United States provided modest military aid to South Vietnam and bombed North Vietnamese bases in Cambodia. The only tangible result was that in August 1973 an angry Congress cut off the funds for such bombing. In November 1973, it passed a War Powers Resolution requiring the president to inform Congress within forty-eight hours of any overseas deployment of U.S. forces and to bring the troops home within sixty days unless Congress expressly approved the president’s action.

It is possible, although doubtful, that Nixon and Kissinger might have come up with a scheme to extend aid to the beleaguered South Vietnamese, but the Watergate scandal engulfed the Nixon White House, ending the reign of the Nixon Doctrine. The president was preoccupied with his own survival, not South Vietnam’s. He acknowledged his personal defeat in August 1974, resigning as president—the first president in U.S. history to do so—rather than suffer certain impeachment and conviction.

In January 1975 North Vietnam launched a general invasion, and one million refugees fled from central South Vietnam toward Saigon. The new president, Gerald R. Ford, asked Congress for emergency assistance to “allies fighting for their lives.” An obdurate Congress declined. On April 21, South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu and his government resigned. Ten days later, North Vietnamese forces took Saigon, and Marine helicopters lifted American officials and a few Vietnamese allies from the rooftop of the U.S. embassy, “an image of flight and humiliation etched on the memories of countless Americans,” in the words of the British historian Paul Johnson.Hanoi raised its flag on May 1 and renamed the old capital Ho Chi Minh City. South Vietnam was no more.

But the dominoes had only begun to fall. In mid-April, the communist Khmer Rouge entered the Cambodian capital of Phnom Penh. Their objective was to carry out in just one year the revolutionary changes that had taken more than a quarter-century in Mao’s China. Between April 1975 and the beginning of 1977, the Marxist-Leninists ruling Cambodia killed an estimated 1.5 million people, one-fifth of the population. Widespread atrocities also took place in Laos, which remains under communist rule to this day.

The 1973 Arab-Israeli war (the Yom Kippur War), in which the Soviet Union openly supported Syria and Egypt with a massive sea and air lift of arms and supplies, also set back detente. When the Israelis turned the tide and came close to destroying Egyptian forces along the Suez Canal, Brezhnev threatened to intervene. Nixon put the U.S. military on worldwide alert, causing the Soviets to back off and agree to a ceasefire that included a UN emergency contingent.

This article is part of our larger collection of resources on the Cold War. For a comprehensive outline of the origins, key events, and conclusion of the Cold War, click here.

This article on the Nixon Doctrine is an excerpt from Lee Edwards and Elizabeth Edwards Spalding’s book A Brief History of the Cold War. It is available to order now at Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

You can also buy the book by clicking on the buttons to the left.

Cite This Article

"Nixon Doctrine — A Pragmatic Cold War Strategy" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

April 18, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/nixon-doctrine>

More Citation Information.