The Nullification Crisis, in U.S. history, was the confrontation between the state of South Carolina and the federal government in 1832–33 over the former’s attempt to declare null and void within the state the federal Tariffs of 1828 and 1832.

Nullification Crisis and the Civil War

Responding to the claim that the federal judiciary and not the states had the final word on the constitutionality of federal measures, James Madison’s Report of 1800 argued that “dangerous powers, not delegated, may not only be usurped and executed by the other departments, but. . . the judicial department may also exercise or sanction dangerous powers, beyond the grant of the Constitution… However true, therefore, it may be, that the judicial department, is, in all questions submitted to it by the forms of the Constitution, to decide in the last resort, this resort must necessarily be deemed the last in relation to the other departments of the government; not in relation to the rights of the parties to the constitutional compact, from which the judicial, as well as the other departments, hold their delegated trusts” (emphasis added). Thus the Supreme Court’s decisions could not be considered absolutely final in constitutional questions touching upon the powers of the states.

The most common argument among the early statesmen against nullification is that it would produce chaos: a bewildering number of states nullifying a bewildering array of federal laws. (Given the character of the vast majority of federal legislation, a good answer to this objection is: Who cares?) Abel Upshur, a Virginian legal thinker who would serve brief terms as secretary of the Navy and secretary of state in the early 1840s, undertook to put the fears of opponents of nullification to rest:

If the States may abuse their reserved rights in the manner contemplated by the President, the Federal government, on the other hand, may abuse its delegated rights. There is danger from both sides, and as we are compelled to confide in the one or the other, we have only to inquire, which is most worthy of our confidence.

It is much more probable that the Federal government will abuse its power than that the States will abuse theirs. And if we suppose a case of actual abuse on either hand, it will not be difficult to decide which is the greater evil.

Perhaps the most important nullification theorist was John C. Calhoun, one of the most brilliant and creative political thinkers in American history. The Liberty Press edition of Calhoun’s writings, Union and Liberty, is indispensable for anyone interested in this subject—especially his Fort Hill address, a concise and elegant case for nullification. Calhoun proposed that an aggrieved state would hold a special nullification convention, much like the ratifying conventions held by the states to ratify the

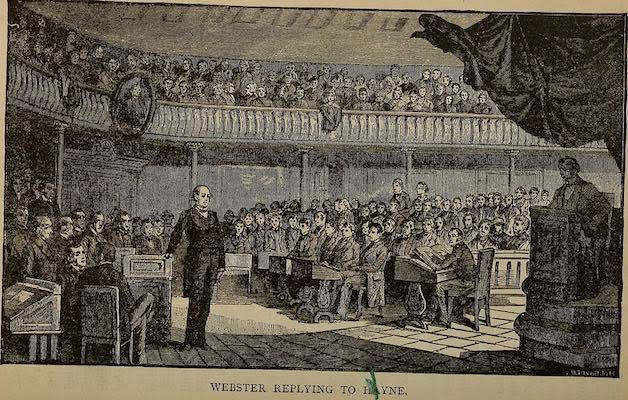

Constitution, and there decide whether to nullify the law in question. This is how it was practiced in the great standoff between South Carolina and Andrew Jackson. When South Carolina nullified a protective tariff in 1832–33 (its argument being that the Constitution authorized the tariff power for the purpose of revenue only, not to encourage manufactures or to profit one section of the country at the expense of another—a violation of the general welfare clause) it held just such a nullification convention.

In Calhoun’s conception, when a state officially nullified a federal law on the grounds of its dubious constitutionality, the law must be regarded as suspended. Thus could the “concurrent majority” of a state be protected by the unconstitutional actions of a numerical majority of the entire country. But there were limits to what the concurrent majority could do. Should three-fourths of the states, by means of the amendment process, choose to grant the federal government the disputed

power, then the nullifying state would have to decide whether it could live with the decision of its fellow states or whether it would prefer to secede from the Union.

That Madison indicated in 1830 that he had never meant to propose nullification or secession either in his work on the Constitution or in his Virginia Resolutions of 1798 is frequently taken as the last word on the subject. But Madison’s frequent change of position has been documented by countless scholars. One modern study on the subject is called “How Many Madisons Will We Find?” “The truth seems to be, that Mr. Madison was more solicitous to preserve the integrity of the Union, than the coherency of his own thoughts,” writes Albert Taylor Bledsoe.

This article is part of our extensive collection of articles on the Antebellum Period. Click here to see our comprehensive article on the Antebellum Period.

Cite This Article

"Nullification Crisis: Catalysis for the Civil War" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

April 20, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/nullification-crisis-civil-war-facts-significance>

More Citation Information.