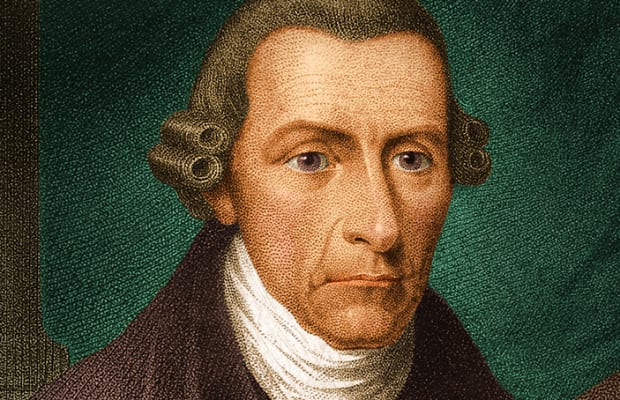

It may seem curious to include Patrick Henry in a list of “forgotten Founders.” His impassioned cry of “give me liberty or give me death!” is one of the more well-known phrases in American history, though it is quite possible that many Americans would think someone other than Henry said it. His name is more recognized than any other in this group, save perhaps John Hancock and Samuel Adams, and their fame comes from a signature and a modern brewing company. Henry has been the subject of several biographies and even a few children’s stories.

But most Americans could probably not list any of his accomplishments other than his famous speech. He has been virtually ignored by the modern historians and those who do discuss his life often focus on his status as an “inconsistent slave owner” or describe him as an unintelligent, smooth-talking, country-bumpkin demagogue. This is due, in part, to Henry’s resolute defense of states’ rights for much of his life and to Jefferson’s unflattering description of the man. But if Dickinson was the “Penman of the Revolution,” then Henry was the “Spokesman of the Revolution” and the man who in many ways made the Revolution possible. Henry was from a typical Virginia frontier family. His father, John Henry, arrived in the American colonies around 1730 from Scotland, and his mother, Sarah Winston, was a second generation American whose father, a Presbyterian, moved to the colonies from Yorkshire, England.

Henry’s parents had modest means, but both were well-respected members of society. His mother was described as a woman of wit and social charm, and his father was a man of good character and education who served as a vestryman in the local parish church and as a colonel of the militia. He owned a small tobacco plantation on the South Anna River called Mount Brilliant. Patrick Henry was born there in 1736 and spent his youth under the tutelage of his father, who taught him to read Latin and appreciate the classic texts. His vigorous schooling was underscored by a hearty plantation life and the moral teachings of his pious minister uncle, the Reverend Patrick Henry, and his mother’s favorite minister, the famous Samuel Davies, later president of Princeton University.

At the age of fifteen, Henry worked as a clerk at a local store. A year later, he opened his own store in partnership with his brother. The store failed, but the young Henry was soon married to Sarah Shelton. This union netted a dowry of six slaves and three hundred acres of poor land, so Henry returned to farming. Fire destroyed the young couples’ home three years later, and Henry was forced to open shop again. Mounting debt and a large family led him to pursue a more lucrative career as a lawyer, and in 1760, he was admitted to the Virginia bar. His practice became one of the most profitable and well known in the region, and in three years he had managed 1,185 suits and won most of his cases.

The Revolution

He purchased a plantation in Louisa County, Virginia, in 1764, and at twenty-nine was elected to the House of Burgesses from that county, taking his seat in May 1765 with the session already in progress. Henry waited only nine days before making an impact in the legislature. While most of the Tory members of the House were absent, Henry presented a series of resolves later known as the “Virginia Stamp Act Resolutions.”

He had shown a willingness to challenge the crown in 1763 during a famous constitutional dispute known as “the Parson’s Cause” (in which the king had vetoed a law passed by the Virginia legislature governing the salaries of Anglican clergy in the colony), but the “Stamp Act Resolutions” trumped the “Cause” in both scope and substance. Henry declared the Stamp Act unconstitutional and argued that only the colonial legislatures possessed the authority to tax the people directly.

This resolve, the fifth, sparked the most debate, passed by only one vote, and was stricken from the record the next day. The other resolutions passed without much confrontation. But many conservative Virginians thought Henry’s speech on the resolutions bordered on treason, particularly the last line where he famously said, “Caesar had his Brutus; Charles the First his Cromwell; and George the Third may profit by their example. . . . ” Henry maintained that he was loyal the king—as long as the king and the British Parliament adhered to their ancient constitutions and recognized that the colonists possessed “all the liberties, privileges, franchises, and immunities that have at any time been held, enjoyed, and possessed by the people of Great Britain.” Henry believed the Stamp Act infringed upon these rights.

The “Stamp Act Resolutions” stirred debate in other colonies and fired a warning shot at the British. The colonies would not lie prostrate and accept unconstitutional authority. Henry became the most popular man in Virginia, if not the colonies, from 1765 to 1770. As each aggressive act by the British Parliament moved the colonies closer to war, Henry solidified his power in Virginia. In 1774, the Virginia governor dissolved the House of Burgesses. Henry led the assembly to Raleigh Tavern in Williamsburg where the group adopted a call for a Virginia convention and asked for all the colonies to meet in a continental congress. At the first Virginia convention in 1774, Henry was chosen to lead the Virginia delegation in the First Continental Congress. He sided with the more radical elements in the Congress and supported a colonial declaration of non-importation of British goods.

Henry was less inclined to make peaceful petitions to the king than were other delegates. He had already decided that the British government would never respect colonial rights under the British constitution. The colonies’ only recourse was independence. Henry and the other members of the Virginia convention decided to meet again in March 1775 at St. John’s Church in Richmond. This meeting was held less than one month before the first shots of the Revolution were fired at Lexington and Concord, and Henry, through a passionate plea against the “illusion of hope,” forced his fellow Virginians to face the facts: “The war is inevitable—and let it come! I repeat it, sir, let it come!” His speech, typically reproduced under the title “Give me Liberty, or Give me Death!” is often characterized as a radical articulation of revolutionary principles. But, in fact, Henry made his case not from any general “rights of man” but from what he regarded as direct violations of the British constitution. He outlined the measures the colonies had taken to forestall war, to no avail. “Our petitions have been slighted; our remonstrances have produced additional violence and insult; our supplications have been disregarded; and we have been spurned, with contempt, from the foot of the throne!”

The convention almost immediately adopted resolutions for mustering, training, and arming the militia of Virginia. Without Henry’s impressive call for action, the convention might not have acted so quickly, particularly before shots had been fired. He was sent to the Second Continental Congress and was later appointed commander-in-chief of the Virginia militia, but many—including Washington—doubted his effectiveness as a military commander, and Henry resigned his commission in February 1776. He attended the third Virginia convention in the spring of that year and took part in the drafting of a new Virginia constitution and a Virginia declaration of independence. Even before the “United States” declared independence, Virginia, as a sovereign political entity, had already done so.

Henry was elected governor in 1776, and he served until 1779. He made lasting contributions not only to Virginia, but to the United States during this period. He sent George Rogers Clark on a military expedition into the western lands beyond the Appalachians in order to both clear the British and solidify Virginia’s claim to the land. It worked. Virginia would control most of what was called the “Northwest territory” until ceding it to the United States in 1784. He also personally intervened and protected George Washington when there was a move to strip him of command. He retired to his plantation in 1779 and enjoyed the company of his second wife, Dorothea Dandridge (the two had eleven children between 1777 and 1799).

The Constitution

Henry could not stay away from politics. After only two years, he returned to the legislature and became a principal opponent of his onetime political ally, Thomas Jefferson. He was re-elected governor in 1784 and faced the most pressing financial crisis in Virginia’s history. The war had destroyed the state’s finances, and paper money created oppressive inflation. Henry favored restoring Loyalist land (ostensibly to raise revenue by taxing the Loyalists and requisitioning their tobacco) and offered veterans land grants in the western territory. Henry became increasingly suspicious of the Northern states during this period, as rumors swirled that they desired a treaty with Spain that would have surrendered American navigation rights on the Mississippi. Henry believed the agrarian South was under attack from Northern commercial interests. He retired from his fifth term as governor in 1786 and re-located his family to Prince Edward County in south-central Virginia. The Virginia legislature decided to send delegates to a “Federal Convention” in 1787 and asked Henry to lead the group. He declined and made clear his opposition to creating a new, stronger central government over the states. The Virginia Ratifying Convention met in June 1788.

Henry attended the convention and used every weapon in his rhetorical arsenal to defeat the Constitution. His opening remarks classified the Constitution as a “consolidated government instead of a confederation. . . . and the danger of such government is, to my mind, very striking.” He questioned whether the work of the convention was valid. “The federal Convention ought to have amended the old system; for this purpose they were solely delegated; the object of their mission extended to no other consideration.” He took issue with the wording of the Preamble, namely the phrase “We the People. . . . ” He foresaw the effects of the phrase and to Henry, it smacked of consolidation. “The fate of . . . America may depend on this. Have they said, We the States? If they had, this would be a confederation. It is otherwise most clearly a consolidated government.”

Moreover, the people could not have created the new document, principally because “the people have no right to enter into leagues, alliances, or confederations. . . . States and foreign powers are the only proper agents for this kind of government.” “We the People,” then was both improper and illegal. He argued that a compact between the “people” and the government fundamentally altered the American system of government, and not for the better. In short, it would “oppress and ruin the people.”

Henry characterized the Constitution as a document that would place power in the hands of a “tyranny.” Even with the guarantee of a bill of rights (which Madison promised), Henry voted against ratification. In his closing remarks, Henry declared that the Constitution violated the principles of the Revolution. The colonies had revolted against a central government that failed to protect their rights; he saw no reason why the people of the states should now seek a new, powerful central government, with a standing army, that could impose a similar tyranny.

Red Hill

Henry ended his political career in the Virginia legislature shortly after the ratification convention, and retired to his plantation, Red Hill, in 1788. Henry had been the unequivocal champion of limited government and states’ rights during the ratification debates, and he refused to serve under the Constitution. Yet, in the 1790s, things began to change as Henry grew suspicious of his former allies in Virginia. By 1798, Henry was a leading supporter of the Federalists in Virginia, a conversion that shocked even his own family. Why the sudden shift? Had he become a “big government” advocate? The answer is no, and there are two possible explanations for his apparent reversal.

The first is personal. The leading members of the new opposition party were Jefferson and Madison, two men Henry considered personal enemies. Jefferson called Henry “the laziest man in reading I ever knew” and believed Henry betrayed him in 1781 when he was under attack for his handling of the war in Virginia while governor. Henry never liked or trusted Madison. Henry despised Madison for his role in framing the Constitution and attempted to have him gerrymandered out of the new Congress in 1789; and he used his power in the Virginia legislature to block Madison from becoming a United States Senator from Virginia.

Neither Jefferson nor Madison wanted Henry involved in their new party, the Republicans (sometimes called the Democratic- Republicans), and both shunned him repeatedly, while at the same time courting Henry’s long-time allies. This was, to them, political revenge. Federalists George Washington and John Marshall knew of the feud and attempted to bring Henry into the Federalist camp. Henry opposed the Republicans not because he liked the Federalists—he didn’t—but because he considered the Republicans hypocrites. He warned them in 1788 of the disastrous effects of the Constitution they supported. “What must I think of those men, whom I myself warned of the danger of giving the power of making laws by means of treaty, to the president and senate, when I see these same men [Madison, for one] denying the existence of that power, which they insisted, in our convention, ought properly to be exercised by the president and senate, and by none other?“

The second concerned his fear of radical democratic theory. Henry admired the British constitution, and spoke reverently of it many times during the Virginia ratification debates. When the leaders of the new Republican Party appeared to embrace the radical tenets of the French Revolution, “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity,” Henry recoiled. Liberty he championed, but the French Revolution destroyed the social order of France through a bloody massacre and wanton destruction of property.

To Henry, the American Revolution was never a war for radical theories such as “equality.” It was fought to preserve “English” liberty and the old, agrarian, social order of Virginia. A “French Revolution” in America would be detrimental to liberty as he viewed it. For example, as governor, he fought against attempts to “separate” church and state, though he believed every man should have freedom of conscience. Henry was not a royalist, but he was a conservative who cherished the Virginia of his past, a society based on ordered liberty.

Henry died in 1799 of stomach cancer. He had just been elected to the Virginia House of Delegates as a “Federalist” but died before he could serve. He left behind an intellectual legacy that exists not in written documents, but in passionate speeches for liberty. Men without a written record are too often ignored by professional historians. Henry has suffered that fate. He said during the ratification debates that “The voice of tradition, I trust, will inform posterity of our struggles for freedom. If our descendants be worthy of the name of Americans, they will preserve, and hand down to their latest posterity, the transactions of the present times; and, though I confess my exclamations are not worthy the hearing, they will see that I have done my utmost to preserve their liberty. . . . ”

Cite This Article

"Patrick Henry: The Revolution’s Spokesman" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

April 24, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/founding-fathers-patrick-henry>

More Citation Information.