The Reconstruction Era is the period (1865-1877) during which the states that had seceded to the Confederacy were controlled by the federal government before being readmitted to the Union. The attempts to reunite the Union and the Confederacy while dismantling the legal and economic system of slavery were met with many failures that largely led to the Jim Crow era and nearly a century of legally-sanctioned racial discrimination.

Following the scorched-earth battles in the Civil War, the newly reunited America worked to rebuild war zones back into farms, towns, cities, and industrial areas. The entire Southern economy would also have to be reconfigured into a system that functioned without slavery, the backbone of labor markets in southern states throughout their existence. Major reform happened to the 11 former Confederate states and the United States as a whole, but former slaves largely did not receive the Constitutional rights promised them at the end of the war.

Two Views of Reconstruction: Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson

While the war was still going on, Lincoln was already thinking ahead to the restoration of the Southern states. (The terminology is important: Lincoln would not have spoken of the readmission of the Southern states, since he believed the Union to be perpetual and indestructible, and secession, therefore, a metaphysical impossibility. The Southern states may think they seceded, but in Lincoln’s mind they never left at all; they had merely rebelled against the federal government.)

Lincoln’s Reconstruction plan was relatively lenient. He granted amnesty to those who took an oath of loyalty to the Union and promised to abide by federal slavery laws. High Confederate officials would need presidential pardons to enjoy their political rights once again. Once 10 percent of a state’s qualified voters took an oath of loyalty to the Union, that state could establish a government and send representatives to Congress.

Andrew Johnson, who became president following Lincoln’s assassination in April 1865, pursued a roughly similar approach, though he added to the list of people requiring presidential pardons anyone who possessed wealth in excess of $20,000. This provision was intended to punish the planter class, which Johnson considered responsible for having persuaded Southerners to support secession. Although he favored the gradual introduction of black suffrage, like Lincoln he did not insist upon it as an immediate requirement.

Carpetbaggers in the Reconstruction Era

A “carpetbagger” was a derogatory term applied by former Confederates to any person from the Northern United States who came to the Southern states after the American Civil War.

A great many contemporary observers believed that the real purpose behind Radical Reconstruction was to secure the domination of the Republican Party in national political life through the newly freed population in the South. The Republicans took for granted that the freed slaves would vote Republican. Connecticut senator James Dixon, for example, argued that “the purpose of the radicals” was “the saving of the Republican Party rather than the restoration of the Union.” This was also the view of General Sherman, who was convinced that “the whole idea of giving votes to the negroes” was “to create just that many votes to be used by others for political uses.” He expressed his displeasure with a plan “whereby politicians may manufacture just so much more pliable electioneering material.” And indeed, Radical Republican Thaddeus Stevens conceded that the votes of the freed slaves were necessary in order to bring about “perpetual ascendancy to the Party of the Union”—that is, the Republican Party.

Carpetbagger Definition US History

Henry Ward Beecher, too, was concerned about the Radicals. Beecher, the brother of Harriet Beecher Stowe (author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin), had been a fierce opponent of slavery, and had helped to arm opponents of slavery in Kansas. Yet even he warned his countrymen of the party spirit that animated the Radicals:

It is said that, if admitted to Congress, the Southern Senators and Representatives will coalesce with Northern democrats and rule the country. Is this nation, then, to remain dismembered, to serve the ends of parties? Have we learned no wisdom by the history of the past ten years, in which just this course of sacrificing the nation to the exigencies of parties plunged us into rebellion and war?

Otto Scott, a twentieth-century Northern writer, observed that Radical vindictiveness following the war, including the Radical insistence that the South was out of the Union and not entitled to congressional representation, strongly suggested that the North’s motives in going to war had not been so pure after all: “To win that war, and then to refuse to allow the South to remain in the Union was not only logically perverse, but a tacit admission that the war had not been about slavery, but—as in all and every war—power.”

In 1866 President Johnson vetoed the Freedmen’s Bureau Bill and the Civil Rights Act of 1866. His veto messages contained detailed critiques of what he considered the constitutionally dubious aspects of the legislation. As Ludwell Johnson explains, “The Freedmen’s Bureau and Civil Rights bills proposed to establish for an indefinite time an extensive, extra-constitutional system of police and judicature with the opportunity, as Johnson correctly pointed out, for enormous abuses of power.” Moreover, Johnson considered it neither fair nor wise to proceed on matters of such gravity while eleven states were still deprived of their representation in Congress.

Radical Republicans in the Reconstruction Era

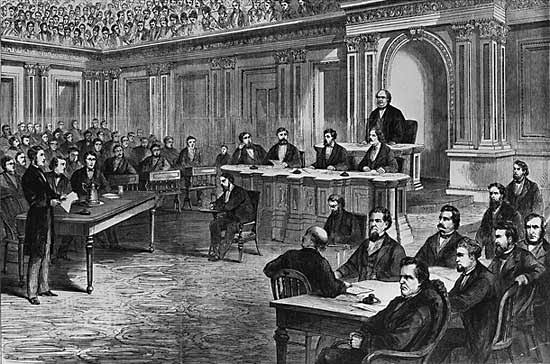

Hiram Revels of Mississippi was elected Senator and six other African Americans were elected as Congressmen from other southern states during the Radical Republicans Reconstruction era.

These policies were not severe enough for the Radical Republicans, a faction of the Republican Party that favored a stricter Reconstruction policy. They insisted on a dramatic expansion of the power of the federal government over the states as well as guarantees of black suffrage. The Radicals did consider the Southern states out of the Union. Massachusetts senator Charles Sumner spoke of the former Confederate states as having “committed suicide.” Congressman Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania went further, describing the seceded states as “conquered provinces.” Such a mentality would go a long way in justifying the Radicals’ disregard of the rule of law in their treatment of these states.

President Johnson’s Reconstruction plan had been proceeding well by the time Congress convened in late 1865. But Congress refused to seat the representatives from the Southern states even though they had organized governments according to the terms of Lincoln’s or Johnson’s plan. Although Congress had the right to judge the qualifications of its members, this was a sweeping rejection of an entire class of representatives rather than the case-by-case evaluation assumed by the Constitution. When Tennessee’s Horace Maynard, who had never been anything but scrupulously loyal to the Union, was not seated, it was clear that no Southern representative would be.

Discussions of Slave Reparations: Beyond the Reconstruction Era

The case for reparations begins with the story of Clyde Ross, an African-American man from Mississippi who moves to the Chicago area in 1947, during the Great Migration. Forget the politicians: What did ordinary soldiers of the North and South have to say about why they took up arms against their neighbors? Acclaimed Civil War historian James McPherson, in his 1997 book For Cause and Comrades: Why Men Fought in the Civil War, consulted a sizable quantity of primary sources, including soldiers’ diaries and their letters to loved ones, to try to determine how the ordinary soldier on each side thought of the war.

In two-thirds of his sources—the same proportion among Northern and Southern fighting men—soldiers said it was due to patriotism. Northern soldiers, by and large, said they were fighting to preserve what their ancestors had bequeathed to them: the Union. Southern soldiers also referred to their ancestors, but they typically argued that the real legacy of the Founding Fathers was not so much the Union as the principle of self-government. Very often we see Southern soldiers comparing the South’s struggle against the U.S. government to the colonies’ struggle against Britain. Both, in their view, were wars of secession fought in order to preserve self-government.

Cite This Article

"The Reconstruction Era (1863-1877): The Great Rebuilding" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

April 18, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/the-reconstruction-era>

More Citation Information.