The Zimmermann Telegram: Words Of War

[Was it fears for its citizenry or its sovereignty that pushed America’s Congress into declaring war on Germany in 1917? Dan McEwen looks at the unintended consequence of WW1’s most infamous telegram.]

One of the most enduring questions about WW1 is why the shooting didn’t stop at the end of 1914 when the short war everyone expected had turned into the bloody stalemate of the trenches. Why didn’t the military leaders stop the insanity and make peace? One country, Germany tried in 1915, only to literally torpedo its efforts.

Germany was winning on the battlefield but losing the war at home, its economy strangled by the British navy’s blockade. When Erich von Falkenhayn assumed command of the German General Staff in 1915, he was asked what the best strategy would be to which he is said to have replied; “Seek peace, we’ve lost.” Instead, Germany’s military junta secretly asked the U.S. government to forward a proposal to London that it would end its submarine cordon around Britain if in turn the Royal Navy’s lifted its crippling blockade of German ports. Since this would reduce the threat to American cargo ships, the powers that be in Washington began diplomatically twisting Britain’s arm to agree to this compromise.

Back-channel talks were going on even as the newest flagship of Britain’s venerable Cunard Lines, the RMS Lusitania, at the time the world’s biggest and fastest luxury liner, was backing out of its berth in New York, with 1,959 passengers and crew on board, bound for Liverpool. Six days later, on May 7th, Captain Walther Schwieger commanding submarine U-20 on it’s way back to home port, spotted the Lusitania as it emerged from a dense fog 11 miles off the coast of Ireland and fired his last torpedo at the great ship. It sank in just 20 minutes, taking 1,195 passengers, including 128 Americans and all talk of limiting the naval war to the bottom of the Atlantic ocean.

Americans were incandescent with outrage over the sinking but in the White House, Woodrow Wilson, who’d campaigned on a promise to keep America out of the war, did just that. A whole week later, his government got around to officially responding to the death of its citizens with the full force of…a note. Sent to Berlin by Secretary of State Williams Jennings Bryan, a die-hard pacifist, the note merely reiterated America’s objections in principle to unrestricted submarine warfare. No actual threats were made as Bryan feared offending Germany into taking even greater action which might really force the US to enter the war.

Two years pass and the killing continues on an industrial scale. Verdun, The Somme, Isonzo River, Gorlice-Tarnow, Jutland, Gallipolli consume millions of soldiers’ lives and even more civilians. Starvation stalks the streets of all European capitals. Millions of homeless, hungry refugees roam the countryside. 1916 was a year of epic crop failures. By 1917, “All of the European powers are racing to collapse and the only question is who collapses first,” observes USAWC Professor of Russian Studies, David Stone Ph.D.

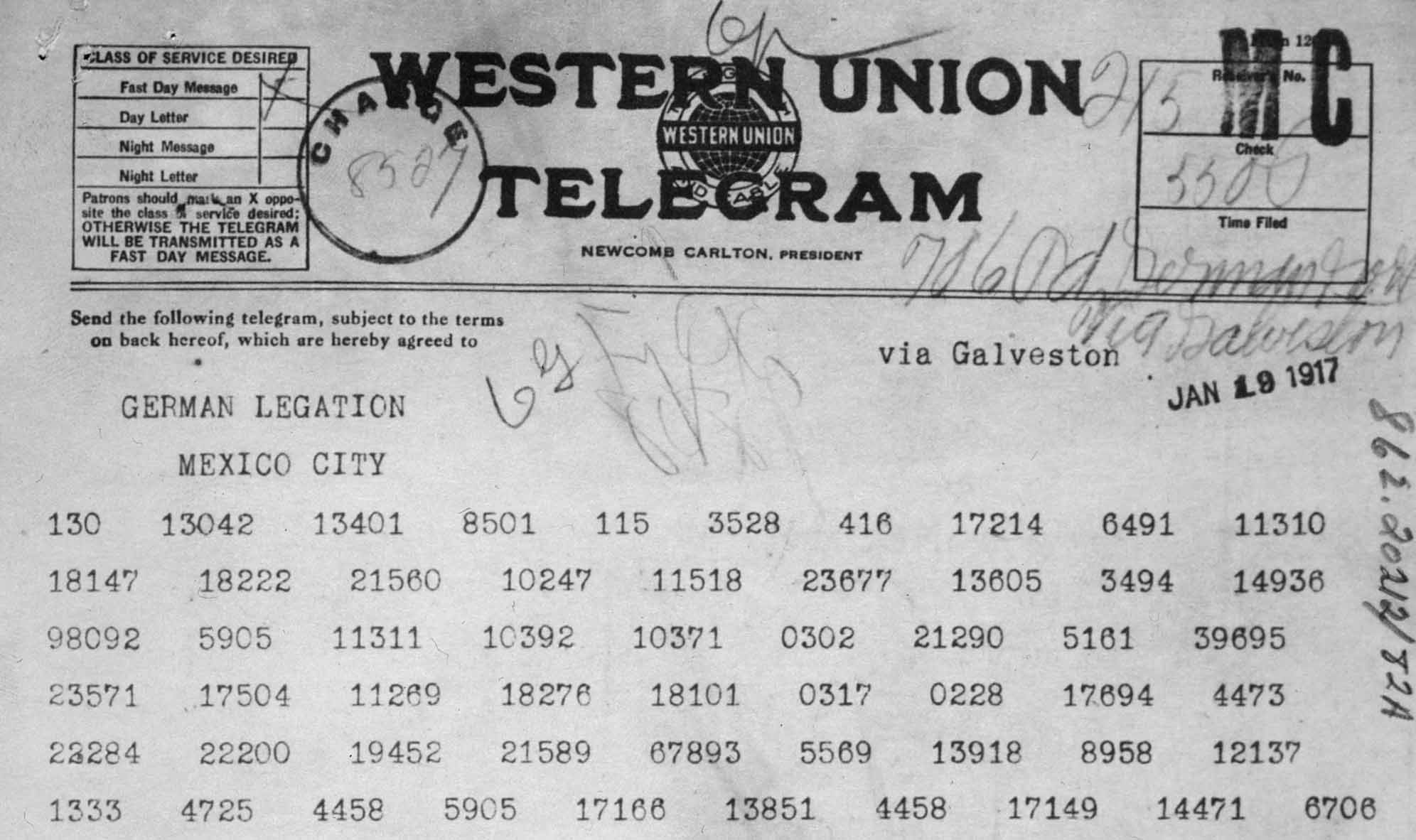

And so, in desperation, on January 17th Germany attempts to goad and/or bribe Mexico into attacking America to reclaim the territory it lost in the Spanish-American War [1898]. Foreign Secretary Arthur Zimmermann sends the following coded telegram to the German ambassador in Mexico, Heinrich von Eckhardt, for him to present to the Mexican government:

We intend to begin on the first of February unrestricted submarine warfare. We shall endeavor in spite of this to keep the United States of America neutral. In the event of this not succeeding, we make Mexico a proposal of alliance on the following basis: make war together, make peace together, generous financial support, and an understanding on our part that Mexico is to reconquer the lost territory in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona. The settlement in detail is left to you. You will inform the President of the above most secretly as soon as the outbreak of war with the United States of America is certain, and add the suggestion that he should, on his own initiative, invite Japan to immediate adherence and at the same time mediate between Japan and ourselves. Please call the President’s attention to the fact that the ruthless employment of our submarines now offers the prospect of compelling England in a few months to make peace.

Whatever military advantage Berlin imagined this alliance would gain them, for example, the diversion of U.S. military resources from the Western Front, required the element of surprise to be effective. In a chain of events worthy of a James Bond spy novel, British intelligence foiled Zimmermann’s clever plot by intercepting and decoding the Zimmermann telegram. The Germans made it easy for them.

Foreign Secretary could not send his inflammatory telegram directly to his embassy in Mexico City because the British had cut the trans-Atlantic cables to prevent exactly that kind of direct communication. But, in a gesture of goodwill President Wilson hoped would soften Berlin’s heart, he allowed the Germans to send their diplomatic messages via the American embassy in Berlin. Un-coded messages only! But Zimmermann’s minions cajoled the embassy staff into letting them send just one coded message.

British code-breakers in Room 40 at the Admiralty intercepted the message and immediately realized the value of the telegram. Although long-simmering anti-German sentiment in the U.S. had reached a boiling point after the Lusitania sinking, the isolationists in Congress held firm. The Zimmermann telegram was the perfect lever to move America into the war on the Triple Entente’s side. There was just one catch. They would have to prove the telegram was legitimate and not simply a ploy to get America into the war and to do that, they would have to reveal to the Americans and the Germans that they had cracked their diplomatic codes! The military, not to mention political blowback of that being discovered gave the code-breakers pause. They held onto the telegram for three weeks while they put in place plausible explanations for how they had come across the Zimmermann telegram.

In the meantime, Mexico’s President Venustiano Carranza took the German proposal seriously enough to ask his generals for a feasibility study. They gave the idea a unanimous and overwhelming thumbs down. At the time Mexico was embroiled in a civil war that threatened to topple Carranza. Why give his opposition a chance to unite with the much stronger American army against him? He also seriously doubted Germany could deliver on its promise of “generous financial support”. Berlin was already paying the Austro-Hungarians a million marks a month to stay in the war and had all but admitted they couldn’t come up with as much as Carranza would have liked. And even if Mexico did take back all their lost land, it would be impossible to hold onto it against the inevitable American counter-attack. Carranza sent a thanks-but-no-thanks reply to Zimmermann.

On February 1st Germany announced the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare. Two days later, the United States broke off diplomatic relations. Woodrow Wilson was finally shown Zimmermann’s handiwork on February 24 and was said to have expressed “much indignation”, wanting to publish it immediately. Concerns about protecting Room 40’s secrets caused him to delay until March 1, 1917, while cover stories were concocted. They proved unnecessary when two days later Zimmermann compounded his blunder by publicly admitting to sending the telegram. That sealed Germany’s fate.

On April 4th, 1917, the U.S. Senate voted 82-6 to approve a resolution declaring war with Germany. Two days later, Congress also approved it. Over two million Doughboys would arrive in France in time to blunt Germany’s last great offensive in 1918.

Dan McEwen is a former corporate wordsmith who writes about military history. Contact him at: danielcmcewen@gmail.com

Sources – Online Lectures, Webinars & TV Documentaries

The U-Boat Campaign and Experiences 1914-1918, Graham Kemp

Between The Rock And A Hard Place, Gary Armstrong

The Russian Disasters of 1915, David Stone

The Short War Assumption, Nicholas Lambert

British Naval Strategy in 1914, Phillip Patee

The German Home Front 1918, Scott Stephenson

The First World War, TV series

The True Cost of Peace After WW1, TV Series

The Great War in Numbers, TV series

also:

Wikipedia, History Net, Encyclopedia Britannica other public sources

Cite This Article

"The Zimmermann Telegram: Words Of War " History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

April 25, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/the-zimmermann-telegram-words-of-war>

More Citation Information.