On October 22, 1944, Patton met with his commander, General Omar Bradley, and Bradley’s chief of staff to discuss plans for taking the French city of Metz and then pushing east into the Saar River Valley, a center of Germany’s armaments industry. Bradley, believing that a strong push might well end the war, argued for a simultaneous attack by all of the Allied armies in Europe.

Patton pointed out that there was not enough ammunition, food, or gasoline to support all the armies. There were enough supplies, however, for one army. Patton’s Third Army could attack twenty-four hours after getting the signal. After a vigorous debate, Bradley conceded. Patton was told that the attack could take place any time after November 5, and that aerial bombardment would be available before-hand.

The Allies were really fighting three enemies, Patton told Bradley—the Germans, time, and the weather. The weather was the most serious threat. The Third Army’s sick rate equaled its battle casualty rate. Patton was never one to delay an attack, convinced that each day’s delay gave the enemy more time to prepare. “The best is the enemy of the good” was one of his favorite maxims. It would be better to attack as soon as Bradley could provide him with supplies.

But Patton could not control the weather, which affected weapons, aircraft, and the movement of troops. A student of history, Patton was keenly aware of weather’s role in a major operation or campaign. When Kublai Khan attacked the Japanese island of Kyushu with his fleet of forty-four hundred ships in 1281, he encountered a typhoon that destroyed half his fleet. The Japanese saw the storm as a divine wind sent by the gods to save them. In his invasion of Russia in 1812, Napoleon was unprepared for Russia’s brutal climate, and thousands of his soldiers perished in the severe winter. He lost more men to cold, famine, and disease than to Russian bullets. Napoleon’s defeat confirmed Emperor Nicholas I’s dictum that Russia has two generals in which she can confide: Generals January and February.

But Patton could look to more recent lessons about weather and battle. Only four months earlier the fate of the Allied invasion of Europe hung on the course of a storm in the English Channel. A break in the weather on June 6 allowed the amphibious assault on Normandy to proceed. Two weeks later, one of the most severe storms ever to strike Normandy sank or disabled a number of Allied ships and wiped out the American Mulberry artificial harbor off Omaha Beach. The Allied war effort was virtually shut down for five days.

When Patton had completed all his preparations for battle, he turned to the Bible and entrusted everything, including the weather, to God. His diary entry for November 7, 1944, reads:

Two years ago today we were on the Augusta approaching Africa, and it was blowing hard. Then about 1600 it stopped. It is now 0230 and raining hard. I hope that too stops.

Know of nothing more I can do to prepare for this attack except to read the Bible and pray. The damn clock seems to have stopped. I am sure we will have great success.

At 1900, Eddy and Grow came to the house to beg me to call off the attack due to the bad weather, heavy rains, and swollen rivers. I told them the attack would go on. I am sure it will succeed. On November 7, 1942, there was a storm but it stopped at 1600. All day the 9th of July 1943, there was a storm but it cleared at dark.

I know the Lord will help us again. Either He will give us good weather or the bad weather will hurt the Germans more than it does us. His Will Be Done.

The Saar campaign was launched on November 8, 1944. After one month’s fighting, Patton’s Third Army had liberated 873 towns and 1,600 square miles. In addition, they had killed or wounded an estimated 88,000 enemy soldiers and taken another 30,000 prisoner. Patton next prepared for the breakthrough to the River Rhine, a formidable natural obstacle to the invasion of Germany by the Allies. The attack was set for December 19.

***

In early December 1944, the headquarters of the Third Army was in the Caserne Molifor, an old French military barracks in Nancy in the region of Lorraine, a ninety-minute train ride from Paris. At eleven o’clock on the morning of December 8, Patton telephoned the head chaplain, Monsignor James H. O’Neill: “This is General Patton; do you have a good prayer for weather? We must do something about those rains if we are to win the war.”

One account of what happened after Patton’s telephone call to O’Neill is related by Colonel Paul Harkins, Patton’s deputy chief of staff. It appears as a footnote in War As I Knew It, a book based on Patton’s diaries and published in 1947, after his death.

On or about the fourteenth of December, 1944, General Patton called Chaplain O’Neill, Third Army Chaplain, and myself into his office in Third Headquarters at Nancy. The conversation went something like this:

General Patton: “Chaplain, I want you to publish a prayer for good weather. I’m tired of these soldiers having to fight mud and floods as well as Germans. See if we can’t get God to work on our side.”

Chaplain O’Neill: “Sir, it’s going to take a pretty thick rug for that kind of praying.”

General Patton: “I don’t care if it takes a flying carpet. I want the praying done.”

Chaplain O’Neill: “Yes, sir. May I say, General, that it usually isn’t a customary thing among men of my profession to pray for clear weather to kill fellow men.”

General Patton: “Chaplain, are you trying to teach me theology or are you the Chaplain of the Third Army? I want a prayer.”

Chaplain O’Neill: “Yes, sir.”

Outside, the Chaplain said, “Whew, that’s a tough one! What do you think he wants?” It was perfectly clear to me. The General wanted a prayer—he wanted one right now— and he wanted it published to the Command.

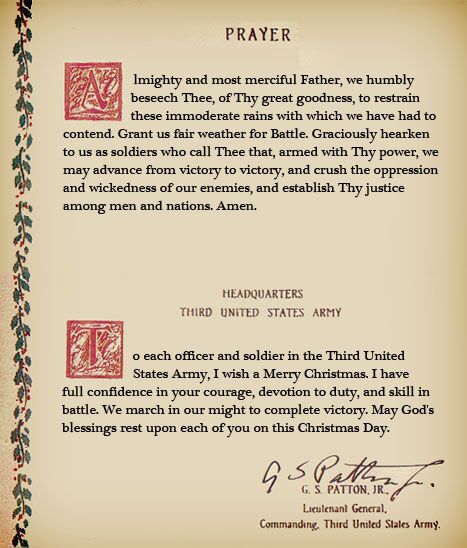

The Army Engineer was called in, and we finally decided that our field topographical company could print the prayer on a small-sized card, making enough copies for distribution to the army. It being near Christmas, we also asked General Patton to include a Christmas greeting to the troops on the same card with the prayer. The General agreed, wrote a short greeting, and the card was made up, published, and distributed to the troops on the twenty-second of December.

The year after the publication of War As I Knew It, Monsignor O’Neill felt compelled to write his own account of the prayer’s origin, which was published in The Military Chaplain magazine as “The True Story of the Patton Prayer.” O’Neill complained that “the footnote on the Prayer by Colonel Paul D. Harkins. . . . while containing the elements of a funny story about the General and his Chaplain, is not the true account of the prayer incident or its sequence.”

O’Neill maintains that he told Patton over the telephone that he would research the topic and report back to him within an hour. After hanging up, O’Neill looked out at the immoderate rains that had plagued the Third Army’s operations for the past three months. As he searched through his prayer books, O’Neill could find no formal prayers pertaining to weather, so he composed an original prayer which he typed on a three-by-five-inch card:

Almighty and most merciful Father, we humbly beseech Thee, of Thy great goodness, to restrain these immoderate rains with which we have had to contend. Grant us fair weather for Battle. Graciously hearken to us as soldiers who call upon Thee that, armed with Thy power, we may advance from victory to victory, and crush the oppression and wickedness of our enemies and establish Thy justice among men and nations.

“If the general would sign the card, it would add a personal touch that I am sure the men would like,” said the chaplain. So Patton sat down at his desk, signed the card, and returned it to O’Neill.

The general then continued, “Chaplain, sit down for a moment. I want to talk to you about this business of prayer.” Patton rubbed his face in his hands, sat silently for a moment, then rose up and walked to the high window of the office where he stood with his back to O’Neill, watching the falling rain. O’Neill later recalled,

As usual, he was dressed stunningly, and his six-foot-two powerfully built physique made an unforgettable silhouette against the great window. The General Patton I saw there was the Army Commander to whom the welfare of the men under him was a matter of personal responsibility. Even in the heat of combat he could take time out to direct new methods to prevent trench feet, to see to it that dry socks went forward daily with the rations to troops on the line, to kneel in the mud administering morphine and caring for a wounded soldier until the ambulance came. What was coming now?

“Chaplain, how much praying is being done in the Third Army?” inquired the general.

“Does the general mean by chaplains, or by the men?” asked O’Neill.

“By everybody,” Patton replied.

“I am afraid to admit it, but I do not believe that much praying is going on. When there is fighting, everyone prays, but now with this constant rain—when things are quiet, dangerously quiet, men just sit and wait for things to happen. Prayer out here is difficult. Both chaplains and men are removed from a special building with a steeple. Prayer to most of them is a formal, ritualized affair, involving special posture and a liturgical setting. I do not believe that much praying is being done.”

Patton left the window, sat at his desk and leaned back in his swivel chair. Playing with a pencil, he began to speak again.

“Chaplain, I am a strong believer in Prayer. There are three ways that men get what they want; by planning, by working, and by Praying. Any great military operation takes careful planning, or thinking. Then you must have well-trained troops to carry it out: that’s working. But between the plan and the operation there is always an unknown. That unknown spells defeat or victory, success or failure. It is the reaction of the actors to the ordeal when it actually comes. Some people call that getting the breaks; I call it God. God has His part, or margin, in everything. That’s where prayer comes in. Up to now, in the Third Army, God has been very good to us. We have never retreated; we have suffered no defeats, no famine, no epidemics. This is because a lot of people back home are praying for us. We were lucky in Africa, in Sicily, and in Italy. Simply because people prayed. But we have to pray for ourselves, too. A good soldier is not made merely by making him think and work. There is something in every soldier that goes deeper than thinking or working—it’s his ‘guts.’ It is something that he has built in there: it is a world of truth and power that is higher than himself. Great living is not all output of thought and work. A man has to have intake as well. I don’t know what you call it, but I call it religion, prayer, or God.”

O’Neill continues,

He talked about Gideon in the Bible, said that men should pray no matter where they were, in church or out of it, that if they did not pray, sooner or later they would “crack up.” To all this I commented agreement, that one of the major training objectives of my office was to help soldiers recover and make their lives effective in this third realm, prayer. It would do no harm to reimpress this training on chaplains. We had about 486 chaplains in the Third Army at that time, representing 32 denominations. Once the Third Army had become operational, my mode of contact with the chaplains had been chiefly through Training Letters issued from time to time to the Chaplains in the four corps and the 22 to 26 divisions comprising the Third Army. Each treated of a variety of subjects of corrective or training value to a chaplain working with troops in the field.

“I wish,” said Patton, “you would put out a Training Letter on this subject of Prayer to all the chaplains; write about nothing else, just the importance of prayer. Let me see it before you send it. We’ve got to get not only the chaplains but every man in the Third Army to pray. We must ask God to stop these rains. These rains are that margin that holds defeat or victory. If we all pray, it will be like what Dr. Carrel said, it will be like plugging in on a current whose source is in Heaven. I believe that prayer completes that circuit. It is power.”

With that the general rose from his chair, indicating that the meeting was concluded, and O’Neill returned to his office to prepare the training letter Patton had requested.

The day after O’Neill had shown Patton the prayer for fair weather for battle and the accompanying Christmas greeting, he presented the general with Training Letter No. 5. Patton read it and directed that it be circulated without change to all of the Third Army’s 486 chaplains, as well as to every organization commander down to and including the regimental level. In total, 3,200 copies were distributed over O’Neill’s signature to every unit in the Third Army. As the chaplain noted, however, strictly speaking it was the Third Army commander’s letter, not O’Neill’s. The order came directly from Patton himself. Distribution was completed on December 11 and 12.

TRAINING LETTER NO. 5

December 14, 1944 Chaplains of the Third Army:

At this stage of the operations I would call upon the chaplains and the men of the Third United States Army to focus their attention on the importance of prayer.

Our glorious march from the Normandy Beach across France to where we stand, before and beyond the Siegfried Line, with the wreckage of the German Army behind us should convince the most skeptical soldier that God has ridden with our banner. Pestilence and famine have not touched us. We have continued in unity of purpose. We have had no quitters; and our leadership has been masterful. The Third Army has no roster of Retreats. None of Defeats. We have no memory of a lost battle to hand on to our children from this great campaign.

But we are not stopping at the Siegfried Line. Tough days may be ahead of us before we eat our rations in the Chancellery of the Deutsches Reich.

As chaplains it is our business to pray. We preach its importance. We urge its practice. But the time is now to intensify our faith in prayer, not alone with ourselves, but with every believing man, Protestant, Catholic, Jew, or Christian in the ranks of the Third United States Army.

Those who pray do more for the world than those who fight; and if the world goes from bad to worse, it is because there are more battles than prayers. “Hands lifted up,” said Bossuet, “smash more battalions than hands that strike.” Gideon of Bible fame was least in his father’s house. He came from Israel’s smallest tribe. But he was a mighty man of valor. His strength lay not in his military might, but in his recognition of God’s proper claims upon his life. He reduced his Army from thirty-two thousand to three hundred men lest the people of Israel would think that their valor had saved them. We have no intention to reduce our vast striking force. But we must urge, instruct, and indoctrinate every fighting man to pray as well as fight. In Gideon’s day, and in our own, spiritually alert minorities carry the burdens and bring the victories.

Urge all of your men to pray, not alone in church, but everywhere. Pray when driving. Pray when fighting. Pray alone. Pray with others. Pray by night and pray by day. Pray for the cessation of immoderate rains, for good weather for Battle. Pray for the defeat of our wicked enemy whose banner is injustice and whose good is oppression. Pray for victory. Pray for our Army, and Pray for Peace.

We must march together, all out for God. The soldier who “cracks up” does not need sympathy or comfort as much as he needs strength. We are not trying to make the best of these days. It is our job to make the most of them. Now is not the time to follow God from “afar off.” This Army needs the assurance and the faith that God is with us. With prayer, we cannot fail.

Be assured that this message on prayer has the approval, the encouragement, and the enthusiastic support of the Third United States Army Commander.

With every good wish to each of you for a very Happy Christmas, and my personal congratulations for your splendid and courageous work since landing on the beach.

***

The 664th Engineer Topographical Company worked around the clock to reproduce 250,000 cards bearing the prayer for fair weather and Patton’s Christmas greeting. The cards and Training Letter No. 5 were distributed by December 14. Two days later, the U.S. armies in Europe were engaged in the greatest battle ever fought by American forces. The outcome of that battle, and possibly of the entire Allied war effort in Europe, would turn on the weather.

Patton’s adjutant, Colonel Harkins, later wrote:

Whether it was the help of the Divine guidance asked for in the prayer or just the normal course of human events, we never knew; at any rate, on the twenty-third, the day after the prayer was issued, the weather cleared and remained perfect for about six days. Enough to allow the Allies to break the backbone of the Von Runstedt offensive and turn a temporary setback into a crushing defeat for the enemy.

General Patton again called me to his office. He wore a smile from ear to ear. He said, “God damn! Look at the weather. That O’Neill sure did some potent praying. Get him up here. I want to pin a medal on him.”

The Chaplain came up the next day. The weather was still clear when we walked into General Patton’s office. The General rose, came from behind his desk with hand out-stretched and said, “Chaplain, you’re the most popular man in this Headquarters. You sure stand in good with the Lord and the soldiers.” The General then pinned a Bronze Star Medal on Chaplain O’Neill.

Everyone offered congratulations and thanks and we got back to the business of killing Germans—with clear weather for battle.

On Christmas Eve, Patton and Omar Bradley attended a candle-light church service in Luxembourg City, sitting in a box once used by Kaiser Wilhelm II. Patton ordered a hot turkey dinner for every soldier in the Third Army on Christmas Day. To ensure that his order was carried out, he spent the bitterly cold day driving from one unit to another. Sergeant John Mims, Patton’s driver throughout the war, recalled, “We left at six o’clock in the morning. We drove all day long, from one outfit to the other. He’d stop and talk to the troops; ask them did they get their turkey, how was it, and all that.” His diary entry for that day is classic Patton: It was “a clear cold Christmas, lovely weather for killing Germans, which seems a bit queer, seeing Whose birthday it is.” The troops were cheerful but “I am not, because we are not going fast enough.”

In the spring, as the Third Army’s advance continued with clear weather, Patton again thanked the Lord for good weather: “I am very grateful to the Lord for the great blessing he has heaped on me and the Third Army, not only in the success which He has granted us, but in the weather which He is now providing.”

Additional Resources About George S. Patton

Cite This Article

"When Patton Enlisted the Entire Third Army to Pray for Fair Weather" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

April 17, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/when-patton-enlisted-the-entire-third-army-to-pray-for-fair-weather>

More Citation Information.