The Stuarts were the United Kingdom’s first kings. For the first time, two thrones were combined when King James VI of Scotland became also King James I of England.

Click here to see more posts in this category. Scroll down to see more articles about the history of Stuarts.

Tudor and Stuart Timeline

The Tudor and Stuart Monarchs and some of the main events of their reigns

Why is Guy Fawkes Celebrated?

Also known as Bonfire Night or Firework Night, Guy Fawkes is celebrated every year on the 5th of November in England (and some other countries). The history of Guy Fawkes dates back to 1605, when a group of Catholic extremists planned to assassinate King James I and hopefully get a catholic monarch on the throne. Guy Fawkes was the unfortunate soul who was put in charge of guarding the explosives that they have placed underneath the House of Lords. He was discovered and arrested, bringing an end to the Gunpowder plot and saving the king’s life. To celebrate the fact that their King survived an attempt to kill him, people lit bonfires all over London. A couple of months after the incident, the “Observance of 5th November Act” was passed as an annual public holiday.

Interesting Facts about Guy Fawkes

Guy Fawkes has been celebrated for over 400 years already, although Guy was not the main conspirator. Legend has it that the word, “guy” actually used to mean “ugly and repulsive,” after the name of Guy Fawkes. After years frequent use, it lost the negative connotation and just became a synonym for “man.” The 2,500kg gunpowder stashed beneath the House of Lords had the potential of causing damage in a 500 meter radius, according to the estimates of physicists.

Timeline – The Tudor and Stuart Monarchs

A detailed Timeline showing the Tudor and Stuart Monarchs and some of the main events of their reigns.

The Stuarts – Great Fire of London 1666

Sunday 2nd September 1666

Weather Report – hot, dry and windy

The Thames water level was very low following a hot summer

Early hours

The fire began in the Pudding Lane house of baker Thomas Farriner. When questioned later Farriner said that he had checked all five fire hearths in his house and he was certain that all fires were out. Nevertheless, when the family were woken by smoke in the early hours of the morning, the fire was so well established that the family could not use the stairs had to escape through an upstairs window.

3a.m.

The fire was so well established that it could be seen from a quarter of a mile away.

Early morning

The Lord Mayor was advised to order the demolition of four houses. He decided not to issue the order because the city would then be responsible for re-building those houses. The fire spread destroying houses west of Pudding Lane. The City’s water engine was also destroyed.

7 am

Samuel Pepys’s maid reported to him that more than 300 houses had been destroyed.

Samuel Pepys kept a diary of events

Mid-morning

News of the fire spread through the city and the streets were filled with people running to escape the fire.

Sunday Night

The fire had burned for half a mile to the East and North of Pudding Lane. King Charles II had been informed of the fire and he had instructed the Mayor to pull down any houses necessary to stop the spread of the fire. However, in a City where the houses were very tightly packed, pulling down enough houses to stop the fire before the fire took hold was a difficult, almost impossible task.

Monday 3rd September 1666

Weather Report: hot dry and windy

Early morning

The fire continued to spread and householders had to choose whether to help the fire-fighting effort or attempt to save goods from their own houses. The Thames was full of boats laden with property rescued from houses that had burnt down.

Profiteers made money by hiring carts and boats at high prices. Most people could not afford their prices and could only save what they could carry.

Late Morning

To reduce the numbers of people in the area of the fire, an order was given that carts could not be brought near to the fire.

Charles II attempted to bring some order to the City by establishing eight fire posts around the fire with thirty foot soldiers assigned to each. His brother, the Duke of York (below), was put in charge.

Late Evening

Because the wind was blowing from the East the fire had spread eastwards more slowly. Fire-fighters managed to prevent Westminster School from being destroyed although it was badly damaged.

The fire was now 300 yards from the Tower and orders were given for extra fire engines to be sent to prevent its destruction. Many of London’s wealthiest citizens had taken their money and valuables to the Tower for safekeeping.

Tuesday 4th September 1666

Weather Report: hot, dry and windy

Early morning

The fire showed no sign of stopping. All attempts to check its spread had failed and the fire-fighters were getting very tired.

Afternoon

All carts, barges, boats and coaches had been hired out.

8 p.m.

The roof of St Paul’s cathedral caught fire.

End of the Day

This had proved to be the most destructive day of the fire. St Paul’s cathedral was among the many buildings destroyed on this day.

Wednesday 5th September

Weather Report: hot, dry but NO wind.

Early Morning

The fire continued to burn but, due to the fact that the wind had dropped, it was not spreading so rapidly.

Mid day

The destruction of a number of houses in Cripplegate had stopped the spread of the fire and had allowed fire-fighters to put it out.

Evening

All fires in the West of the City had been put out.

Thursday 6th September

Weather Report: hot, dry, but no wind

Early Evening

The fire was finally put out.

It had caused a huge amount of damage:

87 churches, including St Paul’s cathedral, 13,200 houses

Fortunately, only 6 people lost their lives, far less than the number that would have died from the plague if the fire had not happened.

The Stuarts – Fire and Fire – Fighting

The risk of fire was great in Stuart England. People used candles for light and open fires for cooking. Houses were built close together and were made out of wood. Tradesmen used large ovens and often kept supplies of fuel in their houses and the many inns had stables attached to them filled with hay and straw.

This picture shows a group of musicians. They are sitting next to an open fire, over which their food is cooking. The room is lit by a candle on the wall. The fire place and the roof are made from wood and there seems to be mats on the floor. It is easy to see that this type of house would set fire very quickly.

There were many fires in seventeenth century London. A fire in 1633 destroyed houses on London Bridge and in 1643 another fire caused £2,880 worth of damage. In 1650 seven barrels of gunpowder exploded in a fire in Tower Street that made 41 houses uninhabitable.

People did not have house insurance and if their house was damaged by fire they had to rely on the charity of other people to replace their possessions.

Many Puritans believed that fire was a punishment from God for man’s sinfulness. In the years before 1666, Puritans who criticised Charles II’s love of women and good living predicted that there would be a ‘Great Fire’.

As early as 1200 laws had been passed banning people from thatching their roofs. By 1600 most houses in London did not have thatched roofs.

In 1620 a new order was made that new buildings should be made from brick or stone and that top floors should not jut out into the street.

Suburbs appointed officers who inspected houses for fire hazards and fined owners if they did not remove the hazard.

Householders were instructed to investigate any smell of smoke and raise the alarm if necessary.

At night it was the night-watchman’s job to guard against fire and in hot weather householders were often told to leave buckets of water outside their doors in case of fire.

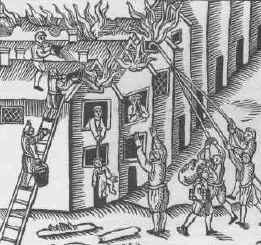

Fire – Fighters

Much of the equipment used by seventeenth century fire-fighters is very similar to that used today:

Fire Hooks

These were used to pull down roof tiles or even buildings to prevent the spread of fire.

Fire Buckets

Made out of leather, these buckets, filled with water, were passed along a chain of people from the water supply to the fire.

This picture shows fire hooks being used to remove roof tiles. Buckets of water are being passed up a ladder to the men on the roof.

Pick Axes

These were used to dig up water pipes which were cut open.

Water Squirts

Hand-held water squirts were developed that allowed the fire-fighter to aim the jet of water at the fire.

Fire Engines

Fire engines were developed in the seventeenth century and were introduced in large cities from around 1625. These ‘engines’ allowed a force of water to be directed at the heart of the fire. In order for any fire to be put out quickly and easily, a good supply of water was needed. Although the new fire engines had tanks that were filled with water, they were soon emptied. They were refilled with water from the river, passed in buckets along a chain of people from the river to the fire.

An early fire engine. Notice the woman on the left hurrying to the river for another bucket of water.

Although the cities and towns of England in the seventeenth centuries were able to fight and put out fires, it was vital that they reached the fire before it became too big. Failure to stop a fire in its infancy could result in destruction of buildings and lives.

The Stuarts – The Plague Doctor

The plague doctor was a common fixture of the medieval world, with his bird-like costume that was believed to resist the plague.

People in the fourteenth century did not know what caused the plague and many believed it was a punishment from God. They did realise that coming into contact with those infected increased the risk of contracting the disease yourself. Cures and preventative measures were not at all effective.

| Suggested Preventions and Cures | How they were supposed to work | What they actually did | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Carry Flowers or wear a strong perfume | The smells would help to ward away the disease | Nothing | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Drink hot drinks | The victim would then sweat out the disease | Nothing | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Carry a lucky charm | The charm would ward off the disease | Nothing | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Loading... Loading... | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Use leeches to bleed the victim | This would remove infected blood | Nothing | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Smoke a pipe of tobacco | The smoke would ward off the disease | Nothing | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Give a strong dose of laxatives | This would cause the victim to completely empty his bowels, thus removing the disease. | Strong doses of laxatives can cause death from dehydration. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coat the victims with mercury and place them in the oven. | The combination of mercury and heat from the oven would kill off the disease. | This could actually increase the likelihood of death – mercury is poisonous and the heat from the oven caused serious burns. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Many doctors, knowing that they could do nothing for plague victims, simply didn’t bother trying to treat the disease. Those that did made sure that they were as protected as possible from the disease by wearing the ‘uniform’ shown above.

Leather Hat

The hat was made of leather. It was worn to show that the man was a doctor and also to add extra protection to the head.

Beak

The beak that was attached to the mask was stuffed with herbs, perfumes or spices to purify the air that the doctor breathed when he was close to victims.

Glass Eye

Glass eyes were built into the mask to make sure that the eyes were fully protected.

Mask

The mask covered the head completely and was gathered in at the neck for extra protecti

Gown

The full-length gown was made out of thick material which was then covered with wax. Underneath the gown the doctor would wear leather breeches.

Leather Gloves

The doctor wore leather gloves to protect his hands from any form of contact with the disease.

Wooden Stick

The Plague Doctor carried a wooden stick so that he could drive people who came too close to him away.

The Stuarts – Great Plague 1665

Bubonic Plague, known as the Black Death, first hit the British Isles in 1348, killing nearly a third of the population. Although regular outbreaks of the plague had occurred since, the outbreak of 1665 was the worst case since 1348.

London – 1665

- 100,000 people – Dead!

- 40,000 dogs – destroyed!

- 200,000 cats – destroyed!

London had changed little since this engraving was made in 1480. Houses were tightly packed together and conditions insanitary – ideal conditions for the plague to spread, particularly during the hot summer of 1665.

Spring 1665

When plague broke out in Holland in 1663, Charles II stopped trading with the country in an attempt to prevent plague infested rats arriving in London. However, despite these precautions, plague broke out in the capital in the Spring of 1665. Spread by the blood-sucking fleas that lived on the black rat.

June 1665

The Summer of 1665 was one of the hottest summers recorded and the numbers dying from plague rose rapidly. People began to panic and the rich fled the capital. By June it was necessary to have a certificate of health in order to travel or enter another town or city and forgers made a fortune issuing counterfeit certificates.

July 1665

The temperature and the numbers of deaths continued to rise. The Lord Mayor of London, desperate to be seen to be doing something, heard rumours that it was the stray dogs and cats on the streets that were spreading the disease and ordered them to be destroyed. This action unwittingly caused the numbers of deaths to rise still further since there were no stray dogs and cats to kill the rats.

Bring out your dead!

Those houses that contained plague victims were marked with a red cross. People only ventured into the streets when absolutely necessary preferring the ‘safety’ of their own homes. Carts were driven through the streets at night. The driver’s call of ‘bring out yer dead’ was a cue for those with a death in the house to bring the body out and place it onto the cart. Bodies were then buried in mass graves.

November 1665

The numbers of deaths from the plague reached a peak in August and September of 1665. However, it was November and the onset of cold weather that brought a drastic reduction in the number of deaths. Charles II did not consider it safe to return to the capital until February 1666.

The Stuarts – Charles I – The Slide to Civil War

Charles I came to the throne in 1625 after the death of his father, James I. Like his father, he believed in the Divine Right of Kings. Although only parliament could pass laws and grant money for war, because they refused to do as he wished, Charles chose to rule without them.

Charles made repeated mistakes throughout his reign that took the country into Civil War and ultimately led to his death on January 30th 1649.

Charles made mistakes in the following areas:

Relationships

Money

Religion

Scotland

Ireland

Parliament

Relationships

In the first year of his reign, Charles married Princess Henrietta Maria of France, a Catholic. Parliament were concerned about the marriage because they did not want to see a return to Catholicism and they believed that a Catholic Queen would raise their children to the Catholic faith.

Instead of listening to the advice of his Parliament, Charles chose the Duke of Buckingham as his main advisor. Parliament disliked Buckingham and resented his level of power over the King. In 1623 he had been responsible for taking England to war with Spain and parliament used this to bring a charge of treason against him.

However, the King dismissed parliament in order to save his favourite. In 1627, Buckingham led a campaign into France which saw the English army badly defeated. In 1628, while preparing for a naval invasion of France, Buckingham was assassinated.

Money

The monarch’s income was paid out of customs duties and when a new King or Queen came to the throne parliament voted for their income to be paid for life. In Charles I’s case, though, it was only granted for one year. The members of parliament wanted to make sure that Charles did not dismiss them. Their plan did not work, Charles chose to rule alone and found his own way of getting money.

Ship Money

It had always been the custom that in times of war, people living on the coast, would pay extra taxes for the defense of the coastline by naval ships.

In 1634, Charles decided that ‘ship money’ should be paid all the time. One year later he demanded that people living inland should also pay ‘ship money’. The people were not pleased and a man named John Hampden refused to pay the tax until it had been agreed by parliament.

The case went to court and the judge found Charles’ actions to be legal. The people had no choice but to pay.

In 1639, Charles needed an army to go to Scotland to force the Scots to use the English Prayer book. A new tax was introduced to pay for the army. People now had to pay two taxes and many simply refused. Many of those jailed for not paying the taxes were released by sympathetic jailors. By 1639 most of the population was against Charles. ‘Ship Money’ was made illegal in 1641.

Religion

The Protestants had been upset by Charles’ marriage to Catholic Henrietta Maria of France. They were even more upset when Charles, together with Archbishop Laud, began making changes to the Church of England. It was ordered that churches be decorated once again and that sermons should not be just confined to the Bible. A new English Prayer Book was introduced in 1637.

Scotland

Charles also demanded that the new English Prayer Book be used in Scottish Churches. This was a very big mistake. The Scots were more anti-Catholic than the English and many of them were Puritans. There were riots in Scotland against the new service and Charles was forced to raise an army to fight against the Scots. The English army was defeated by the Scots and Charles foolishly agreed to pay Scotland ?850 per day until the matter was settled. Money he did not have!

Ireland

The Irish Catholics were fed up with being ruled by English Protestants who had been given land in Ireland by James I.

In 1641, news reached London that the Catholics were revolting. As the news travelled it was exaggerated and Londoners learned that 20,000 Protestants had been murdered. Rumours spread that Charles was behind the rebellion in a bid to make the whole of the United Kingdom Catholic.

An army had to be sent to Ireland to put the rebellion down but who was to control the army. Parliament was worried that if Charles had control of the army he would use it to regain control over Parliament. In the same way, if Parliament controlled the army they would use it to control the King. It was a stalemate.

Parliament

One of Charles I’s major mistakes was that he was unable to gain the co-operation of his parliament. His determined belief in the Divine Right of Kings led to his dismissing parliament in 1629 and ruling without them. The fact that he did not have a parliament to grant him money meant that he had to tax his people heavier and introduce unpleasant taxes such as ship money (see above). It was only when Charles needed an army to fight against Scotland that he was forced to recall parliament in 1640. This parliament remained in office for so many years that it is known as the Long Parliament.

The Long Parliament

Having been dismissed from office for eleven years, this parliament was determined to make the most of being recalled and Charles’ favourite, Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Strafford, of treason. Strafford was executed in May 1641.

In November 1641, parliament presented the King with a list of complaints called the Grand Remonstrance that asked for the power of bishops to be reduced and for Charles’ councillors to be men trusted by parliament. Not all members of parliament were in favour of it and it was only passed by 159 votes to 148.

In January 1642 Charles made what was the most foolish move of his reign. He burst into the Houses of Parliament with 400 soldiers and demanded that the five leading MPs be arrested. The five MPs had had advance warning and had fled.

Charles demanding the arrest of the five MPs

In June 1642 the Long Parliament passed a new set of demands called the Nineteen Proposals that called for the King’s powers to be greatly reduced and a greater control of government to be given to parliament. This move divided parliament between those who supported the Nineteen Proposals and those who thought parliament had gone too far.

Both Parliament and Charles began collecting together their own armies. War was inevitable. People were forced to choose sides and on 22nd August 1642, the King raised his standard at Nottingham.

The Stuarts – The Pilgrim Fathers

When James I came to the throne, he adopted a moderate Protestant religious policy. Both Catholics and Puritans were forbidden to practice their religions. Many extreme Puritans left England for Holland where Puritanism was accepted.

In 1607 Walter Raleigh had founded the colony of Virginia in America and a number of English companies had begun trading tobacco and other products between the colony and England.

One stock company, anxious to protect their business interests in Virginia recruited 35 members of the radical, Puritan, English Separatist Church, who had fled to Holland. The stock company agreed to finance the voyage for them and in return they would look after the company’s business in Virginia. Other Puritans keen to start a new life in America joined the voyage.

The Mayflower left the port of Southampton in August 1620 but was forced to put into Plymouth for repairs. The 102 passengers and 30 crew eventually left Plymouth for America on 16th September 1620 and steered a course for Virginia. The ship was a double-decked, three-masted vessel and initially the voyage went well but then storms blew up which blew them off course.

Land was sighted on November 9th and anchor was dropped. A landing party of sixteen men left the ship on November 15th but failed to find a suitable site to establish a settlement. They set sail again and resumed their search. On December 17th they reached Plymouth Harbour and dropped anchor.

On December 21st the first of the Pilgrim Fathers set foot on what would become Plymouth settlement. The harsh winter weather meant that they were unable to build adequate shelter and many of the travellers died during that first winter. Those that survived the winter went on to build houses and defences. In the late spring of 1621 a native American Samoset Indian offered to show the settlers how to farm the land and become self-sufficient if the men would help them fight a rival tribe. The settlers agreed and the Plymouth settlement flourished.

This painting shows the Pilgrim Fathers landing at Plymouth Harbour. Their ship, the Mayflower, can be seen in the distance.

December 21st is known as Forefather’s Day in America.

The Stuarts – Puritans

Towards the end of Elizabeth’s reign, an extreme branch of the Protestant religion was becoming more popular. They called themselves Puritans.

This picture clearly shows the simple, plain clothing worn by the Puritans. Their clothing was usually black, white or grey and they lived a simple and religious life. The importance of religion to the Puritans is shown in the picture by the woman carrying a Bible. They believed that hard work was the key to gaining a place in heaven. Sundays and Holy days were strictly observed, with these days being devoted entirely to God.

Throughout the reign of James I the Puritans gained power in Parliament. By the time of Charles I’s reign they had gained enough support in Parliament to pass laws imposing their views about living on all English people.

Activities Banned by the Puritans:

Horse Racing, cock-fighting and bear baiting

Any gathering of people without permission

Drunkenness and swearing

Theatre-going, dancing and singing

Games and sports on Sundays (including going for a walk)

Gambling

Visiting brothels

Many public houses were closed down.

Puritan Religion

The Puritans were fiercely anti-Catholic and believed that churches should be plain and free from all kinds of ornament. They believed that all mankind was basically sinful, but that some would be saved because of Christ’s death. Central to their belief was the act of conversion. Conversion could take two forms – either a blinding flash during which the converted could cry out or fall to the ground – or it could be the end result of a period of preparation. Puritans believed that discipline was a vital part of human life and that frivolity was a sign of giving in to temptation.

This modern-day Presbyterian church would have been acceptable to the Puritans of the seventeenth century. It is built in a plain stone with wooden panelling and pews. There is no elaborate decoration, just a plain cross above the altar and a cross on the wooden pulpit.

The Stuarts – The Gunpowder Plot

A Conspiracy or Not?

‘Remember, remember, the fifth of November.

Gunpowder, treason and plot.’

Or was it?

Read the two different versions of the Gunpowder Plot and decide for yourself…

The Facts

A small group of Catholics, Robert Catesby, Guido (Guy) Fawkes, Thomas Winter, John Wright and Thomas Percy decided to blow up the King on the State opening of Parliament. They hoped that this would lead to a Catholic King coming to the throne. Guido (Guy) Fawkes was an explosives expert who had served with the Spanish army in the Netherlands.

The group rented a cellar beneath the Houses of Parliament and stored 20 barrels of gunpowder, supplied by Guido Fawkes. The date for the deed was set for November 5th. They recruited others sympathetic to their cause including Francis Tresham whose brother-in-law, Lord Monteagle, was a member of Parliament. Concerned for his brother-in-law’s safety, Tresham sent him a letter advising him not to attend Parliament on November 5th.

Monteagle alerted the authorities and a search of the Houses of Parliament led to the discovery of Guido Fawkes standing guard over the barrels of gunpowder. He was tortured and revealed the names of the conspirators. Catesby and Percy and two others were killed resisting arrest. The others were tried for treason and executed.

The Protestant View – The Conspirators were Guilty

This picture shows the conspirators hatching the plot to blow up the King and parliament. They are grouped close together which shows that they are hatching a secret plot.

Robert Catesby, Guido (Guy) Fawkes, Thomas Winter, John Wright and Thomas Percy were known to be Catholics.

Guido Fawkes was an explosives expert. He had only recently returned to England maybe specifically to set the explosives.

Francis Tresham was only thinking of his brother-in-law’s safety when he sent the letter.

Gunpowder was not normally kept in the cellars under the Houses of Parliament. It was obviously put there by the conspirators.

Guido Fawkes revealed the names of the conspirators.

The Catholic View – The Conspirators were framed by the Protestants

Many historians today agree with the Catholics of the time that the Gunpowder Plot conspirators were framed by James I’s chief minister, Robert Cecil.

Cecil hated the Catholics and wanted to show them to be against the country. It is believed that Francis Tresham, who sent the warning note to his brother-in-law, may have been working for Cecil. There is evidence to support this view:

This picture showing the conspirators, was made by a Dutchman who had never seen the conspirators.

Cecil is quoted as saying ‘..we cannot hope to have good government while large numbers of people (Catholics) go around obeying foreign rulers (The Pope).’ This shows how much he hated the Catholics and wanted rid of them.

Lord Monteagle received the warning letter at night. The night he received it was the only night in 1605 that he stayed at home. Could he have been waiting for it?

All available supplies of gunpowder were kept in the Tower of London.

The cellar was rented to the conspirators by a close friend of Robert Cecil.

All of the conspirators were executed except one – Francis Tresham.

The signature on Guy Fawkes’ confession did not match his normal signature.

The Stuarts and Their Monarchs: 1603 – 1714

For more information on the Stuarts and other counter-intuitive facts of ancient and medieval history, see Anthony Esolen’s The Politically Incorrect Guide to Western Civilization.

The first English monarch of the Stuarts, James I of England and VI of Scotland, succeeded to the throne of England when Elizabeth I died. He was the son of Mary Queen of Scots by her second husband Lord Darnley, and great-great grandson of Henry VIII’s sister Margaret.

In all there were seven monarchs among the Stuarts: James I, Charles I, Charles II, James II, William III and Mary II Anne. The period from 1649 to 1660 was an interregnum (time without a monarch), that saw the development of the Commonwealth under Oliver Cromwell.

James I (1603 – 1625)

The accession of James VI of Scotland as James I of England, united the countries of England and Scotland under one monarch for the first time.

James believed in the Divine Right of Kings – that he was answerable to God alone and could not be tried by any court. He forbade any interpretation of church doctrine different to his own and made Sunday Church-going compulsory. Catholics were not allowed to celebrate Mass and he refused to listen to Puritan demands for church reform, instead authorising use of the King James Bible that is still in existence today.

James I also introduced English and Irish Protestants into Northern Ireland through the Ulster Plantation scheme and tried to keep England at peace with the rest of Europe. Although he was a clever man, his choice of favourites alienated Parliament and he was not able to solve the country’s financial or political problems. When he died in 1625 the country was badly in debt.

Charles I (1625 – 1649)

Charles I came to the throne after his father’s death. He did not share his father’s love of peace and embarked on war with Spain and then with France. In order to fight these wars he needed Parliament to grant him money. However, Parliament was not happy with his choice of favourites, especially the Duke of Buckingham and made things difficult for him.

In 1629 he dismissed Parliament and decided to rule alone for the next 11 years. Like his father he also believed in the Divine Right of Kings and he upset his Scottish subjects, many of whom were Puritans, by insisting that they follow the same religion as his English subjects. The result was the two Bishops Wars (1639-1640) Charles’ financial state had worsened to such a degree that he had no choice but to recall a Parliament whose condemnation of his style of rule would lead the country to Civil War and Charles I to his execution in 1649.

Interregnum Oliver Cromwell (1649 – 1658)

In 1649, Oliver Cromwell took the title Lord Protector of the newly formed republic in England, known as the Commonwealth. His parliament consisted of a few chosen supporters and was not popular either at home or abroad.

Cromwell disliked the Irish Catholics and, on the pretence of punishment for the massacre of English Protestants in 1641, he lay siege to the town of Drogheda in 1649 and killed most of its inhabitants. Having conquered Ireland he declared war on the Netherlands – England’s greatest trade rival. He went on to establish colonies in Jamaica and the West Indies.

Although he faced opposition from those who supported Charles I’s son, Charles II, as the rightful King, (especially the Scots), Oliver Cromwell succeeded in establishing a sound reputation for the Commonwealth by the time of his death in 1658. He was succeeded by his son Richard, who had no wish to rule.

Cromwell’s opponents were easily able to overthrow him and after a period of anarchy the monarchy was restored with the accession of Charles II.

Charles II (1660 – 1685)

After the execution of his father in 1649, Charles assumed the title Charles II of England, and was formally recognised as King of Scotland and Ireland.

In 1651 he led an invasion into England from Scotland to defeat Cromwell and restore the monarchy. He was defeated and fled to France where he spent the next eight years.

In 1660 he was invited, by parliament, to return to England as King Charles II. This event is known as the Restoration.

He is known as the ‘Merry Monarch’ because of his love of parties, music and the theatre and his abolishment of the laws passed by Cromwell that forbade music and dancing.

Charles was extravagant with money and was forced to marry Portuguese Catherine of Braganza for the large dowry she would bring. He continued to have money problems and allied England with France, a move that led to war with the Dutch and the acquisition of New Amsterdam (now New York) for England. Charles II died in 1685.

James II (1685 – 1688)

James II succeeded his brother Charles to the throne. After the Restoration he had served as Lord High Admiral until he announced his conversion to Roman Catholicism and was forced to resign.

He succeeded despite the passing of the Test Acts in 1673 (which barred all Roman Catholics from holding official positions in Great Britain) and the efforts of Parliament to have him by-passed. The Duke of Monmouth immediately mounted an uprising against James II but it was crushed and a series of treason trials known as the Bloody Assizes followed. The Lord Chief Justice, George Jeffreys, sentenced more than 300 people to death and had another 800 forcibly sold into slavery.

The Bloody Assizes led to an increasing number of calls for James to be replaced by his son-in-law, William of Orange and in 1688 the Dutchman was invited to take the English throne. William’s subsequent invasion of England and accession to the throne is known as The Glorious Revolution. James fled to France where he lived until his death in 1701.

William III (1688 – 1702) and Mary II (1688 -1694)

William III and his wife Mary II (daughter of James II), were proclaimed joint sovereigns of England in 1688 following the Glorious Revolution. They were accepted by Scotland the following year, but Ireland, which was mainly Catholic, remained loyal to James II. William led an army into Ireland and James was defeated at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690. Mary II died in 1694 and William ruled alone until his death in 1702.

Queen Anne (1702 – 1714)

Queen Anne was the sister of Mary II and was married to Prince George of Denmark. She was a committed Protestant and supported the Glorious Revolution that deposed her father and replaced him with her sister and brother-in-law. In 1707 the Act of Union formally united the Kingdoms of England and Scotland. She was the last monarch of the Stuarts, as none of her eighteen children survived beyond infancy.

The Stuarts – Bibliography

James VI of Scotland I of England – Scotland’s Kings and Queens

James VI + I – Anniina Jokinen

Charles I – Britannia

Charles II – Britannia

James II – Britannia

William and Mary – Britannia

Queen Anne – Britannia

Guy Fawkes, The Gunpowder Plot and Bonfire Night – Sonja Hyde

Pilgrims and Puritans – Capitol Project

Puritanism in England – The Victorian Web

Pilgrim Fathers – Britannia

The Great Plague – Historic UK

The London Plague of 1665 – Britain Express

This article is part of our larger selection of posts about the Stuart Dynasty. To learn more, click here for our comprehensive guide to the Stuart Dynasty.

Cite This Article

"The Stuarts- Interesting Facts on the First Kings of the United Kingdom" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

April 28, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/stuarts-interesting-facts-on-first-kings-of-united-kingdom>

More Citation Information.