The Fall of Czar Nicholas II

[Dan McEwen is a Canadian novelist [A Force of Nature] and former corporate wordsmith who ventures into the pages of history with endless fascination. [danielcmcewen@gmail.com]

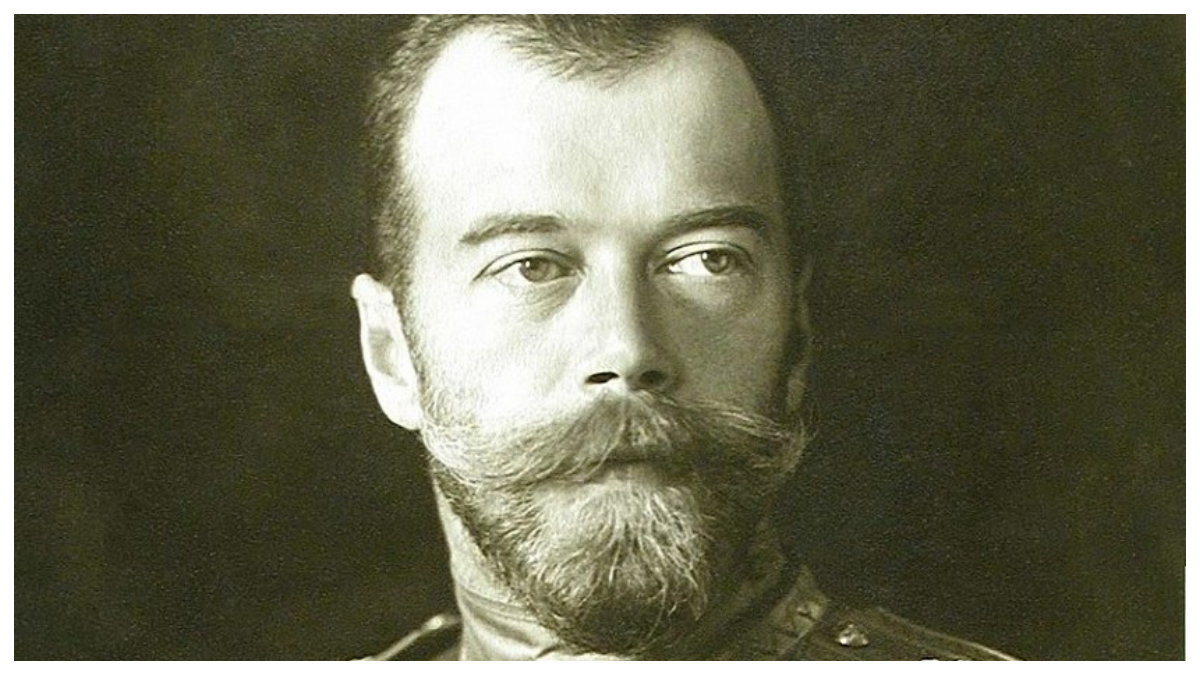

[Although a reluctant czar, Nicholas 2nd resisted every move to limit his powers. Big mistake. Dan McEwen traces the last czar’s path to self-destruction.]

The coronation of Czar Nicholas II was marked by a disaster that cast an ominous shadow over the young czar’s reign. Ironically, it began with a rare act of royal largess. On May 27th, 1896, some 100,000 Moscow residents packed Khodynka Field, a military parade ground, lured by the promise of free food and beer to formally celebrate the coronation. Before the give-away could even start, however, a rumor flashed through the crowd that there wasn’t enough to go around. In the ensuing stampede, over 1,300 celebrants, many women, and children were crushed to death. 1,300 more were injured.

Genuinely distraught, Nicholas wanted to cancel the rest of the festivities but no, there were French diplomats who would be offended if they were not properly received. So he and wife Alexandra dutifully appeared in their bejeweled finery at a gala ball that same evening, seemingly indifferent to the ghastly tragedy. Although he visited the injured in hospitals the following day and compensated families out of his own pocket; “The damage was done,” observes Romanov biographer Edward Crankshaw. “The new czar was on his way to being written off by the people he needed most, not as a brute…but rather as a despicably shallow and frivolous, good-for-nothing.” It was all downhill from there.

While generally acknowledged to have been a loving husband, doting father, and all-around “nice guy”, there’s no question Czar Nicholas II was manifestly unqualified for the monumental task of running the largest country in the world. Sorely lacking in experience, wisdom, or character, he was suddenly and reluctantly thrust into the role of the czar in 1894 by his father’s premature demise. Then aged 26, ‘Nikki’ would achieve none of the greatness of Peter or Catherine. He is remembered only for being the last of the 18 Romanovs who had been a pox on Russian houses since 1613.

Claiming a god-given power, all 18 inflicted on their subjects medieval feudalism so inhumane that African slaves toiling in the American south lived longer, healthier lives than Russian serfs! Serfdom kept the country economically anemic, militarily antiquated, and technologically inferior to other European monarchies. Russian soldiers who chased Napoleon’s army back to Paris in 1812, saw the modern wonders of the City of Light and reported being ashamed of their own country’s impoverishment. A century later, Russian soldiers invading Germany in 1914 shot postmen riding bicycles because they’d never seen bicycles and assumed they were a weapon. More perilous for czardom, the ruthless repression of all dissent, all progress, all attempts to stand upright, built up a volcano of simmering rage that would erupt under the pressure of war.

The so-called “emancipation” of the serfs in 1861 did little more than turn them into laborers to be equally exploited and brutalized by mine and factory owners. Thousands were worked to death, hundreds more were shot for daring to strike. Sadly, their plight elicited little sympathy from Nicholas. He’d already made it crystal clear that re-arranging the nation’s political/economic seating plan more fairly was not going to happen on his watch.

Barely had the crown been placed on his head when representatives from several local assemblies (zemstvos) delivered the ‘Tver Address’ which called for reforms to improve ordinary Russians’ quality of life. Nicholas’ response stunned them. “I want everyone to know that I will devote all my strength to maintain, for the good of the whole nation, the principle of absolute autocracy as firmly and as strongly as did my late lamented father.” In this, he was a man of his word.

In 1901, he called out his army to suppress anti-government unrest 155 times.

By 1909 that number had grown to over 114,000! This repression begat thousands of retaliatory acts of domestic terrorism – bombings, assassinations, arson, looting – that, curiously, targeted not the czar but his middle-level bureaucrats, policemen, and landowners. “There was never any popular movement against the Czar whom the peasants regarded as; “the sun, the source of all beneficence and light,” observed Crankshaw. “Their wrath was directed against the Czar’s officials and landowners whose corruption and greed came between them and the light of the sun.” “If only the Czar knew” was the peasants’ popular refrain. They didn’t realize he knew; he just didn’t care. Still, it was not rebellious peasants who finally compelled the obstinate Czar Nicholas II to make concessions, but rather, a war halfway around the world.

Motivated by the same imperialist ambitions that had the other European powers ‘scrambling’ for colonies all over Asia and Africa, Czar Nicholas II decided in 1904 to expand Russia’s reach into the Pacific. After all, it boasted the biggest army and the fourth-largest navy in the world. What could possibly go wrong?

Pretty much everything. The finely-trained sailors of Japan’s shiny new navy outmaneuvered and outgunned first, the colossally unqualified admirals the czar had appointed to command his Pacific fleet, and then the even more maladroit captains of its antiquated Baltic fleet. When news arrived that both his fleets were sitting on the bottom of the Yellow Sea, Nicholas’s credibility sank even deeper. And then, incredibly, he made things even worse by ordering his guards to fire on a crowd of workers who had come to present him with a petition demanding basic human rights.

With his military judgment, if not his leadership ability, being publicly questioned at home and abroad, a humiliated Nicholas was forced to the negotiating table where reformist politicians presented him with an 11-point resolution calling for personal freedoms and a representative assembly. He countered by issuing The October Manifesto of 1905 which agreed to grant some limited civil freedoms and permit the creation of a representative body, the Duma, to govern the nation’s day-to-day affairs. The country went wild.

Newspaper editorials across the land gushed about these “Days of Freedom”. Russkoe Slovo [Russian Star] trumpeted the news that “throughout the centuries of Russia’s servile existence we have never known a stronger happier moment” Another paper declared; “Russia is joining the common family of bold peoples advancing towards freedom and happiness.” Russia was “on the eve of its liberation… between impenetrable darkness and a bright luminous…future” wrote a Petersburg doctor to friends.

The bulb of that “bright, luminous future” quickly burned out. Regretting the concessions, Czar Nicholas II cravenly clawed them back. For example, in June of 1907, he dissolved the Second Duma after just 3 months, arrested of some its members, and re-wrote Russian electoral law to pack the assembly with representatives of the propertied classes he could rely on to outvote the liberal and revolutionary deputies.

“Time has shattered the foundations for hope” moaned one such disillusioned deputy in 1910. “How many times has the specter of happiness deceived us?” Nothing had changed three years later, prompting a newspaper editor to bemoan; “We find ourselves in such troubled straits because our reality is dismal…and hope has flown away.”

We will never know what would have happened to Russia’s reform movement if an assassination in distant Bosnia hadn’t plunged the world into war in August of 1914, creating the tipping point for the revolution three years later.

What is known is that Russia’s early victories over the Austro-Hungarian and German armies were squandered by bickering generals practicing outmoded tactics, resulting in ‘The Great Retreat of 1915’, which saw the German army push 270 miles into Russia in a; “military disaster that ranks among the greatest in history,” according to U.S. Naval War College professor David Stone. A million Russian soldiers were killed in three months. Twice that number of civilians, caught between advancing Germans and retreating Russians, became destitute refugees, doomed to die of disease or hunger. As always, Nicholas felt no obligation to relieve his subjects’ suffering. The near-mystical bond that held Russians in the thrall of the czars for three centuries was fraying.

It frayed even further when he made the two most fateful choices of his reign. First, he took personal command of the army, believing that his regal presence would inspire the dispirited troops. It didn’t, but being with his troops meant someone had to fulfill his royal duties on the home front, prompting Czar Nicholas II to commit the second error by giving the job to his highly-unpopular, German-born wife. Making herself even more unpopular, ‘Princess Alix’ fell under the spell of a barking mad monk named Rasputin whom she believed was keeping her hemophiliac son Alexis alive. The czarina, who had a long history of being charmed by charlatans, became the licentious shaman’s puppet, firing veteran ministers and bureaucrats according to his whims and replacing them with his pick of corrupt and/or incompetent buffoons. It was just the last straw according to Edward Crankshaw

“The harm she did by causing Czar Nicholas II to leave St. Petersburg and spend his winters at Tsarskoe Selo and his summers at Peterhof, by cocooning him in her claustrophobic apartments, visited only by inferior hangers-on….by helping him to pretend that he was indeed the autocrat and father of his people…is past all computing.” Indeed, Crankshaw ultimately gives up on the hen-pecked czar. “It is profitless and absurd to take any… account of his actions for the remaining three years of his reign. He was at sea and out of control.”

Little wonder then that the mass desertions on the battlefield, mass starvation in the cities, and mass chaos in the palace renewed calls for his abdication. Czar Nicholas IIpigheadedly dismissed the chorus of voices as; “treachery, cowardice, and deceit”. What finally and irrevocably snapped his hold over his subjects began, coincidentally as had the French Revolution; with a march led by women. Still away with his troops, Nicholas telegraphed his guards to disperse the marchers the usual way – with gunfire. Several protesters were killed. The crowd melted away and the guards returned to their barracks.

And then, says author Mark Steinberg, everything changes. The crowds return to the streets. ‘Let them shoot us, we are not going to quit,’ they declare. The troops in their barracks decide it was wrong to shoot their own citizens and return to the streets as well, tying red ribbons to their bayonets and joining the demonstrators. “This mutiny is ultimately what leads the Czars’ generals and ministers to say tell him; ‘You need a bigger concession this time, you must abdicate’.” And this time, he goes, quietly retreating to his family, already under house arrest. Once again the country went wild.

For the seven months after the abdication, the holiday spirit of 1905 returned. Newspapers, pamphlets, postcards, and personal letters bubbled over with talk of; “a joyous, naive, disorderly carnival paradise,” “The revolution seemed like a wonderful holiday…for the first, we were completely free”, “Russia has turned a new page in her history and inscribed on it Freedom” “The dazzling sun appeared” waxed a tabloid newspaper, “foul mists were dispersed. Great Russia stirred. The long-suffering people arose. The nightmare yoke fell. Freedom and happiness forward!”

Amid this “wonderful holiday” loomed an age-old problem. 300 years of mind-numbing, soul-crushing Romanov despotism had left even radicalized Russians too cowed to take the fate of the nation into their own hands. They’d never been allowed to even discuss the topic in public. So instead, power was shared between the union-backed Petrograd Soviet and the Provisional Government which kept the lights on while the Duma deputies sorted out what kind of government to create. Alas, after months of arguing among themselves, the fractious assortment of Social Democrats, Liberals, Mensheviks, Bolsheviks, and die-hard Royalists among others, could not agree on whether to restore the czar or shoot him on sight; form a republic or establish a constitutional monarchy; make the new government capitalist or socialist, etc.

And that was a problem best summed up by journalist Edward R. Murrow; “A nation of sheep will beget a government of wolves.” Sure enough, into the power vacuum created by the Duma’s lofty dithering stepped an apolitical wolf whose only goal was to seize power by violence; whose only plan was to use more violence to keep it. Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov was a forty-something rebel-without-a-cause secretly in the pay of the German government, who knew exactly what to do and it definitely didn’t include any “dazzling sun” of freedom.

Billed as the “Father of the Revolution”, Lenin had no qualms about abandoning his child. The fiery speeches promising Peace, Bread, Land were just so much hot air. The reams of books and editorials in which he championed a better world for the working classes were a convenient ideological sheep’s clothing. As philosopher Albert Camus reminds us; “The welfare of the people…has always been the alibi of tyrants.”

Lenin’s phony revolutionary rhetoric also masked a powerful personal hatred for the Romanovs. His older brother Alexander ‘Sasha” Ulyanov had been hanged in 1887 for a minor role in a foiled assassination plot against the czar. Stricken with grief, Lenin is reported to have vowed; “I’ll make them pay for this, I swear it!” And they did.

Following his abdication, Nicholas asked both the British and then the French governments to give him asylum. Fearing a backlash from their own socialist parties, both countries refused, condemning him to death. He was 49 when together with Alexandra and their five children, he was murdered by drunken thugs on Lenin’s orders in the basement of a guest house far from St. Petersburg on July 17, 1918. Their bodies were dismembered, drenched with acid, set ablaze, and dumped down a mine shaft. They would be recovered only after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1989. So ended the “white” tyranny of the Romanov czars. The worst was yet to come.

In his memoirs, Leon Trotsky, Lenin’s closest lieutenant, recalled a meeting that illustrates why the Bolshevik’s seizure of power was so astonishingly easy. “The [zemstvos] deputies brought candles with them in case the Bolsheviki cut off the electricity and a vast number of sandwiches in case their food was taken from them. Thus democracy entered upon the struggle with dictatorship heavily armed with candles and sandwiches.” It was no contest.

The “joyous forward march to happiness and freedom” was halted and the truth of George Orwell’s claim that; “One does not establish a dictatorship to safeguard a revolution; one makes a revolution in order to establish a dictatorship,” was revealed only too late. Lenin’s coup d’etat initiated the “Red Terror”, a tidal wave of blood-letting that decades later had even Marxist revolutionary Che Guevara reflecting on how; “cruel leaders are replaced only to have the leaders turn cruel”. By the end of the civil war that cemented his power in 1921, Lenin’s career ambitions had put another 10 million Russians in their graves.

Czars or Commissars, apparently it made no difference. In 1613, Russians turned to Romanov autocracy to bring peace and prosperity to their troubled country. In 1917, they turned to Leninist socialism for the same reasons. A century later, he too has been disavowed. 400 years on, the country awaits a leader who will be acclaimed for his/her humanity and nobility in resuming the country’s march towards that “freedom and happiness” it still seeks.

______________________________________________

Sources – Books

In The Shadow of the Winter Palace: Russia’s Drift To Revolution 1825-1917 – Edward Crankshaw, Viking Press, 1976

Three Emperors: Three Cousins, Three Empires and the Road to WW1 – Miranda Carter, Penguin Books, 2009

The Eastern Front 1914-17 – Norman Stone, Penguin Books, 1975

Red Victory: A History of the Russian Civil War – W. Bruce Lincoln, Simon & Schuster, 1989

Sources – Online Lectures

The Rising Spirit of Revolution 1905-1917, Mark Steinberg

The Russian Disasters of 1915, David Stone

The Russian Revolution Sean Kalic / Gates Brown, USAWC,

Lenin & the Russian Revolution, Arthur Herman

Between The Rock and a Hard Place – Gary Armstrong,

Cite This Article

"Czar Nicholas II – The Downfall of Russia’s Last Czar" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

April 27, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/czar-nicholas-ii-the-downfall-of-russias-last-czar>

More Citation Information.