Five years after introducing the world to the blitzkrieg, in concert with fast-moving panzers, the German air force was being hunted to destruction. In 1939 the Luftwaffe was the world’s strongest air force with modern equipment, well-trained aircrews, and combat experience from the Spanish Civil War. However, from its secretive birth in the early 1930s, it was doctrinally a tactical air arm mainly intended to support the German army. Long-range strategic bombers were largely shunned in favor of single- and twin-engine bombers and attack aircraft capable of functioning as ‘‘flying artillery.’’ The concept worked extremely well in Poland, France, Belgium, and elsewhere in 1939–40. It also achieved sensational success in the early phase of Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of Russia in 1941 (German Air Force ww2). However, during the Battle of Britain and subsequently in Russia, Germany paid for its lack of multi-engine bombers capable of destroying enemy industry.

The dominant figure in the Luftwaffe was Reichmarshall Hermann Göering. A noted World War I pilot and leader, he was also an early political supporter of Adolf Hitler and therefore gained full control of German aviation when the Nazis came to power. However, Göering proved out of his depth as a commander in chief, and his air force suffered under his often irrational leadership. Göering demanded control of everything connected with aviation, and got it: antiaircraft defenses, paratroops, POW camps for Allied airmen, even a Luftwaffe forestry service. Ten percent of the Luftwaffe’s strength was committed to ground units, including the superbly equipped Hermann Göering Panzer Division, which fought with distinction in Africa, Italy, and Russia. Some Allied generals frankly considered it the best unit in any army of World War II.

Like the Anglo-American air forces, the Luftwaffe was built around the basic unit of the squadron (Staffel), equipped with nine or more aircraft. Three or four Staffeln constituted a group (Gruppe), with three or more Gruppen per Geschwader, or wing. German organization was more specialized than that of the RAF or USAAF, as there were Gruppen and Geschwadern not only of fighters, bombers, transport, and reconnaissance units of but dive-bomber, ground attack (mainly anti-armor), and maritime patrol aircraft.

Nomenclature can be confusing when comparing the Luftwaffe to the USAAF and RAF. Although the squadron label was common to all three, what the Germans and Americans called a ‘‘group’’ was an RAF ‘‘wing,’’ while an RAF ‘‘group’’ was essentially a Luftwaffe or USAAF ‘‘wing’’—an assembly of squadrons under one command. The American wing (RAF group) largely served an administrative function, whereas in the Luftwaffe and RAF it was a tactical organization.

Above the wing level, the Germans also maintained Fligerkorps (flying corps) and Luftflotte (air fleet) commands. The Allies had no direct equivalent of a Fliegerkorps, which often was a specialized organization built for a specific purpose. For instance, Fliegerkorps X in the Mediterranean specialized in attacks against Allied shipping, flying Ju-87 Stukas and other aircraft suitable for that mission.

Luftflotten were roughly equivalent to the American numbered air forces but nowhere near as large. They were self-contained air fleets (as the name implies) with organic bomber, fighter, and other groups or wings. However, they seldom engaged in the closely coordinated types of missions common to the U.S. Eighth, Ninth, or Fifteenth Air Forces.

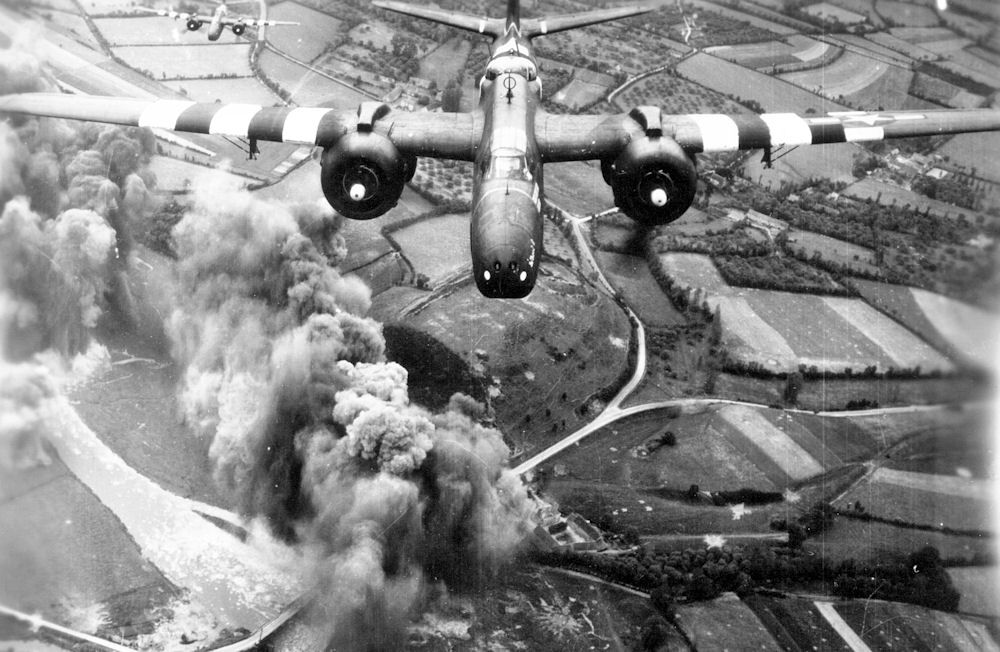

By 1944 the Luftwaffe had been driven from North Africa and the Mediterranean but still fought in Russia, Italy, and western Europe. Spread thin and sustaining horrific losses (as much as 25 percent of fighter pilots per month), Göering’s forces had been worn down by the relentless AngloAmerican Combined Bombing Offensive. The British bombed by night, the Americans by day—the latter escorted by long-range fighters. Though Germany worked successive miracles of production, the experience level of Luftwaffe pilots had entered an unrecoverable spiral.

In preparation for Overlord, Oberkommando der Luftwaffe (OKL) announced that ten combat wings would be committed to the invasion front. However, because of growing Allied air superiority over France and Western Europe, and the increasing need to defend the Reich itself, few aircraft were immediately made available.

Luftflotte Three, responsible for the Channel front, probably had fewer than two hundred fighters and perhaps 125 bombers on 6 June, and few of those were within range of Normandy. The various German sources on that unit’s strength are extremely contradictory, giving figures ranging from about three hundred to more than eight hundred planes. Col. Josef Priller’s postwar history cites 183 fighters in France; that number seems more reliable than most, as Priller had been a wing commander who reputedly led the only two planes that attacked any of the beaches in daylight.

Most Luftwaffe sorties were flown against the invasion forces after dark, but few of the promised reserves materialized from the Reich. Luftwaffe bombers made almost nightly attacks on the Allied fleet and port facilities from 6 June onward, but they accomplished little in exchange for their heavy losses.

The U.S. Army Air Forces chief, Gen. Henry Arnold, wrote his wife that the Luftwaffe had had an opportunity to attack four thousand ships—a target unprecedented in history. Accounts vary, but reputedly only 115 to 150 sorties were flown against the Allied naval forces that night. German aircraft losses on D-Day have been cited as thirty-nine shot down and eight lost operationally.

The Luftwaffe fought as long as fuel and ammunition remained, and it produced some unpleasant surprises in 1944–45. The most significant development was the first generation of jet- and rocket-powered combat aircraft, built by Messerschmitt and Arado. But it was a case of too little too late, and the qualitative superiority of the Me-163, Me-262, and Ar-234 proved irrelevant in the face of overwhelming Allied numbers.

This article on the German Air Force ww2 is from the book D-Day Encyclopedia, © 2014 by Barrett Tillman. Please use this data for any reference citations. To order this book, please visit its online sales page at Amazon or Barnes & Noble.

You can also buy the book by clicking on the buttons to the left.

Cite This Article

"German Air Force in WW2: Luftwaffe’s Terror" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

July 24, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/german-air-force-ww2>

More Citation Information.