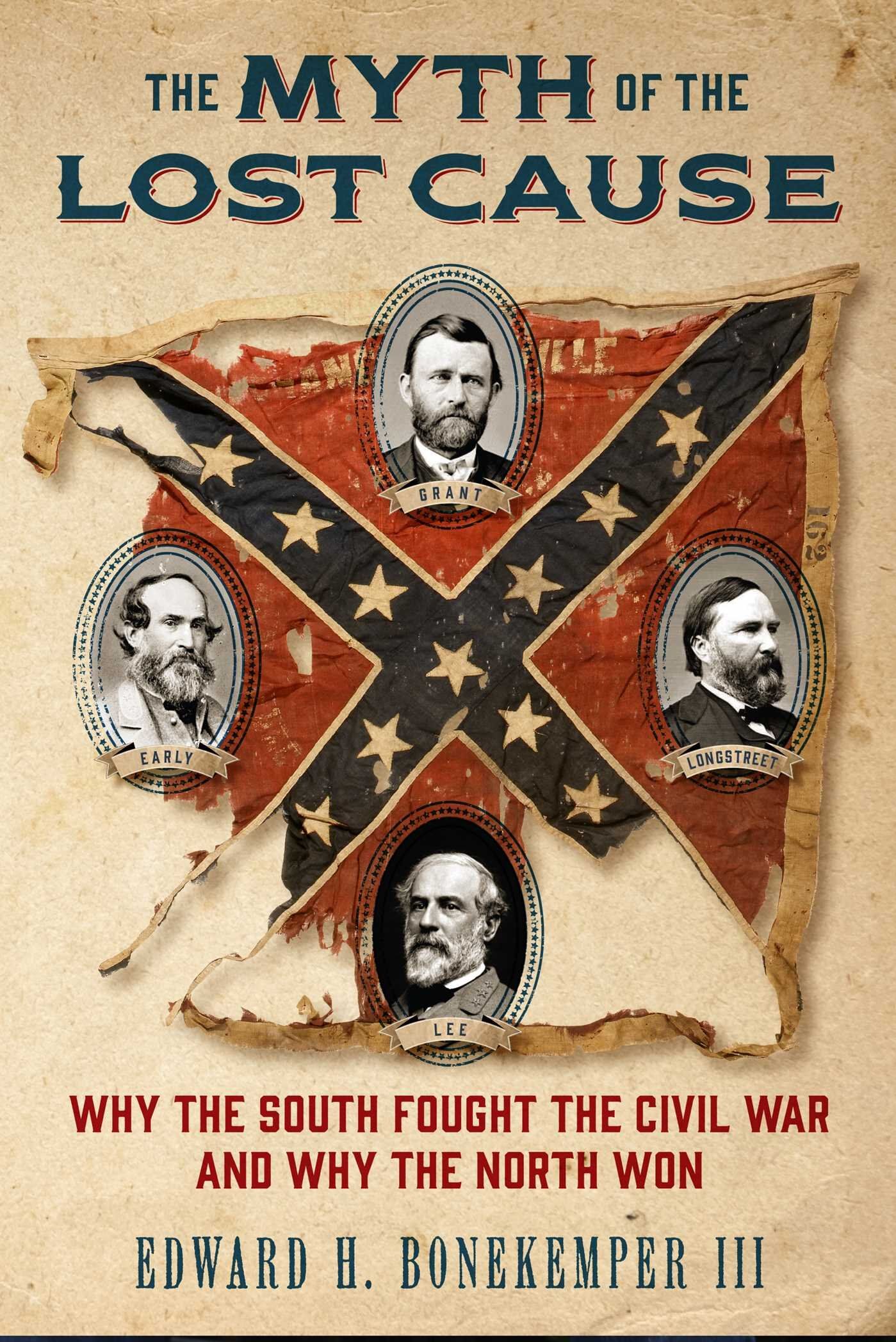

The Myth of the Lost Cause was a constructed historical narrative on the causes of the Civil War. It argued that despite the Confederacy losing the Civil War, their cause was a heroic and just one, based on defending one’s homeland, state’s rights, and the constitutional right to secession.

MYTH OF THE LOST CAUSE

The Myth of the Lost Cause may have been the most successful propaganda campaign in American history. For almost 150 years it has shaped our view of the causation and fighting of the Civil War. As discussed in detail in prior chapters, the Myth of the Lost Cause was just that—a false concoction intended to justify the Civil War and the South’s expending so much energy and blood in defense of slavery.

Contrary to the Myth of the Lost Cause, slavery was not a benign institution that benefitted whites and blacks alike. It was a cruel institution maintained by force, torture, and murder. It thrived on the exploitation of black labor and on the profits made from sales of surplus slaves. The latter practice resulted in the breaking up of black families and the absence of any contract of marriage between slaves. Masters’ rapes of slaves resulted in additional profits, a whitening of the slave population, and white marital discord, which was “remedied” by idolization of white Southern womanhood.

Despite the stories of slaves’ happiness and contentment, whites maintained militias because they were in constant fear of slave revolts and slave escapes. They also hired slave-catchers to capture and return runaway slaves—and also to snatch free blacks off the streets both North and South. The tens of thousands of prewar runaway slaves and the hundreds of thousands of slaves who fled to Union lines during the Civil War were a testament to slaves’ dissatisfaction with their lives under the peculiar institution and their desire for freedom.

Many of the same people who argued that slavery was a prosperous and benevolent practice rather inconsistently contended that the Civil War was unnecessary because slavery was a dying institution, a proposition that became a classic component of the Myth of the Lost Cause. The historical record, however, belies this notion. The booming cotton-based economy, the rise in slave prices to an all-time high in 1860, the amount of undeveloped land in the South, and the expanding use of slaves in manufacturing and other agriculture-related industries all indicated that slavery was thriving and not about to expire. Southerners had only begun to make maximum use of their four- to six-billion-dollar slave property and were not about to relinquish voluntarily the most valuable property they owned. If slavery was a dying institution, why did Southern states complain about the possible loss of billions of dollars invested in slaves, fight for the expansion of slavery into the territories, cite the preservation of slavery as the reason for secession, claim that slavery was necessary to maintain white supremacy, and conduct the war in a manner that placed greater value on slavery and white supremacy than on Confederate victory?

In addition to the economic value of slavery, there was the social value to consider. The institution was based on white supremacy and provided the elite planter class with a means of mollifying the large majority of whites who were not slave-owners. In addition to aspiring to become slave-owners, these other whites could at least endure their low economic and social status by embracing their superiority to blacks in Southern society.

As of 1860, therefore, slavery was a thriving enterprise. It benefitted only whites, treated blacks in a sub-human manner, and promised to return great profits and social benefits for whites for years to come.

A primary tenet of the Myth of the Lost Cause is that slavery was not a primary cause of the Civil War—that war instead was brought about by a desire and clamor for states’ rights. Late-war and postwar apologists for the Confederacy have consistently maintained that slavery had little or nothing to do with secession. Nothing could be further from the truth.

The United States had been embroiled in disputes over slavery ever since the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution were modified, at Southerners’ insistence, to protect and preserve slavery. The Missouri Compromise of 1820, with its focus on slavery in the territories, was the first major indication that the North-South split on the issue was widening. During the 1830s, with the rise of abolitionism in the North, slave revolts (and perceived slave revolts) in the South, and the growth of the Underground Railroad to aid runaway slaves, sectional differences became more heated.

In the 1850s the pot boiled over. The multi-part Compromise of 1850 contained a strengthened fugitive slave provision that caused consternation and defiance in the North and then anger in the South when many Northerners flaunted it. Stephen Douglas’s Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 voided the Missouri Compromise and opened all territories to the possibility of slavery. Northern reaction to that “popular sovereignty” law was so strong that a new Republican Party was formed to oppose any extension of slavery to the territories.

Guerilla warfare between pro- and anti-slavery settlers broke out in Missouri and Kansas. When President James Buchanan in 1857 supported a fraudulent pro-slavery Kansas territorial constitution, Douglas opposed him and split the Democratic party into Northern and Southern wings. Just days after Buchanan’s 1857 inauguration, the Supreme Court issued its notorious Dred Scott decision. The Southern-dominated court said Congress could not prohibit slavery in any territories (as it had done in 1787, 1789, 1820, 1850, and 1854) and that blacks were not U.S. or state citizens and thus had no legal rights.

All these developments, along with the Lincoln-Douglas debates of 1858,1 set the stage for the presidential election of 1860. Slavery in the territories was virtually the only issue in the race. Republican Lincoln wanted slavery in none of them, Southern Democrat John Breckinridge wanted slavery in all of them, Northern Democrat Douglas wanted the issue decided in each territory by popular sovereignty, and Unionist John Bell ducked the issue. Lincoln, of course, won. Despite his assurances that he would take no action against slavery where it existed, Lincoln was labeled an “abolitionist” by many Southern leaders. The seven states of the Deep South seceded before Lincoln took office.

The seceding states made their motives clear in many ways. The Southern press, congressmen, and state leaders railed against Lincoln’s election because they believed they were going to lose the control of the federal government that they had held since 1789. The presidency had been dominated by Southern and Southern-sympathizing presidents (including Buchanan and Franklin Pierce in the 1850s), presidents had nominated Supreme Court justices sympathetic to slavery, and Southerners had consistently dominated Congress through seniority, the Constitution’s “three-fifths” clause, and other means. Southerners were disturbed that a Republican central government would not aggressively support slavery, that Northern states would be better able to undermine the fugitive slave law, and that “free” states would eventually end slavery by amending the Constitution. It was not the concept of states’ rights that was driving them to secession but the fear of losing control of the federal government and thus the ability to support slavery and compel Northern states to do so as well.

One clue that slavery was a cause of secession is found in the 1860 census, which shows that the seven states that seceded before Lincoln’s inauguration had the highest numbers of slaves per capita and the highest percentage of family slave ownership of all the states. The four states of the Upper South that seceded after the firing on Fort Sumter had the next-highest numbers. Finally, the four border slave states that did not secede had the lowest numbers of slaves per capita and the lowest percentage of family slave ownership of all slave states.

But the best evidence that slavery was the driving force behind secession is the statements made by the states and their leaders themselves at the time, including the official state secession convention records, secession resolutions, and secession-related declarations. They railed against “Black Republicans,” the supposedly abolitionist Lincoln, the failure to enforce the Constitution’s fugitive slave clause and federal fugitive slave acts, the threat to the South’s multi-billion-dollar investment in slaves, abolitionism, racial equality, and the threat blacks posed to Southern womanhood. These documents make it clear that slavery was not only the primary cause of secession but virtually the only cause.

As the states of the Deep South were in the process of seceding, moderates in Washington—especially Border State representatives—launched negotiations. The primary “compromise” proposals were those of Kentucky’s Senator John Crittenden. All of them related to one issue: slavery. In fact, they were all aimed at enhancing protections for slavery and alleviating slave states’ fears about threats to it. There could be no question about what was causing secession and driving the nation toward war. Republicans, urged by Lincoln not to reverse the results of the presidential election, defeated Crittenden’s pro-slavery proposals.

Pro-slavery and pro–white supremacy arguments were made by commissioners sent by the Deep South states to urge each other, the Upper South, and border states to secede. The commissioners first advocated for quick secession so the earliest seceding states were not alone; they also pushed for an early convention to form a confederacy. Their letters and speeches contained the same pro-slavery and pro–white supremacy arguments as their states’ secession documents, and they often were embellished with emotional appeals about the horrors the South would suffer if slavery was abolished.

Confederate leaders made similar statements in defense of slavery in the early days of the Confederacy. President Jefferson Davis described the formation of an anti-slavery political party in the North, praised the benefits of slavery, and concluded that the threat to slavery left the South with no choice but to secede.

Vice President Alexander Stephens said that slavery was the cornerstone of the Confederacy, Thomas Jefferson had erred in stating that all men are created equal, and the Confederacy was based on equality of whites and subservience of blacks. After Lincoln issued his Emancipation Proclamation, Robert E. Lee described it as a “savage and brutal policy.”

The Constitution of the Confederacy was similar to that of the United States but added provisions for the protection of slavery. Tellingly, it even contained a supremacy clause conferring final legal authority on the central government, not the states. That provision and the extra protections for slavery reveal the seceding states’ priorities.

After the Confederacy’s formation and the firing on Fort Sumter, four Upper South states (North Carolina, Virginia, Tennessee, and Arkansas) joined the Confederacy, having been entreated to do so by the Deep South on the basis of slavery. Statements of their leaders demonstrate the major role that slavery played in their leaving the Union.

One of the more fascinating indications of the Confederates’ motivation was their failure to deploy virtually any of their three and a half million slaves as soldiers. Adherents of the Myth of the Lost Cause, in order to minimize the role of slavery in secession and the formation of the Confederacy, have alleged that thousands of black soldiers fought for the Confederacy. That did not happen. The evidence reveals instead that although Confederates used blacks as laborers and officers’ “servants,” they could not countenance the arming and related emancipation of slaves.

It was clear to certain Southern military leaders that the outmanned Confederacy needed to resort to slaves as soldiers if they hoped to have a chance of success. Just after the First Battle of Bull Run in July 1861, General Richard Ewell recommended to President Davis the arming of slaves. Davis, has just proclaimed that secession and the Confederacy were all about slavery, rejected the idea.

The need for such an approach became more obvious as a result of the huge rebel casualty counts in 1862 and 1863. Thus, on January 2, 1864, Major General Patrick Cleburne submitted to General Joseph Johnston a well-considered proposal to arm and free slaves. The reaction from Davis, Alexander Stephens, General Braxton Bragg, and most other senior Confederates was extremely hostile. The word “traitor” was bandied about. Cleburne, one of the rebels’ best generals, was never promoted to lieutenant general or corps command.

By late 1864, the Confederates had suffered irreplaceable casualties in Virginia and Georgia, lost Atlanta, lost Mobile Bay and then Mobile, and lost the Shenandoah Valley. Their fate had been sealed by the November reelection of Lincoln, the steel backbone of the Union. That event was followed by the loss of Savannah, as well as the twin disasters at Franklin and Nashville, Tennessee. Therefore, Davis and Lee belatedly began to see that without using slave soldiers the Confederacy was certainly doomed.

Nevertheless, their moderate proposals to arm and free slaves were fiercely resisted by politicians, the press, soldiers, and the people of the South. The opponents made it quite clear that the proposals were inconsistent with the reason for the Confederacy’s existence and the supremacy of the white race. They feared such an approach would lead to black political, economic, and social equality and invoked the ever-reliable doctrine of protecting Southern womanhood.

In early 1865, Sherman marched virtually unimpeded through the Carolinas, Grant tightened his grip on Richmond and Petersburg, and tens of thousands of Union troops were transferred into the Eastern Theater. Despite the increasingly desperate situation, Davis and Lee’s weak proposal to arm slaves was barely passed by the Confederate Congress. Since it did not provide emancipation for slaves and required consent from states and slaves’ owners, the measure was next to worthless. Its implementation was laughable—two companies of black medics were assembled in the Richmond area. The Confederate Congress and people had made it clear that they would rather lose the war than give up slavery.

Slavery hampered Confederate diplomacy and cost the South critical support from Great Britain and France, even though these powers, dependent on Southern cotton and happy to see the American colossus split in half, had good economic and political reasons to support the rebels. When the reality of the slavery problem on the international front finally sank in, last-minute, half-hearted, blundering efforts to trade emancipation for diplomatic recognition failed.

Slavery and white supremacy similarly hampered Confederate efforts to swap prisoners of war with the Union. Since the rebels were greatly outnumbered, they should have been eager to engage in one-for-one prisoner swaps. When blacks began fighting for the Union, however, Davis and Lee refused to exchange any black prisoners on the grounds that they were Southern property. Blacks lucky enough to survive after capture (many did not) were returned to their owners or imprisoned as criminals. Lincoln and Grant insisted that black prisoners had to be treated and exchanged the same as whites. Because the North benefitted militarily, it did not hesitate to stop all prisoner exchanges when Davis and Lee would not back down.

The evidence, then, is overwhelming that, contrary to the Myth of the Lost Cause, the preservation of slavery and its concomitant white supremacy were the primary causes of the Southern states’ secession and their creation of the Confederacy.

Adherents of the Myth of the Lost Cause contend that the South could not have won the Civil War because of the North’s superior industrial, transportation, and manpower resources. Although the Union did have those advantages, its strategic burden was far heavier than the South’s. The Confederacy occupied an enormous territory (equivalent to most of western Europe) that had to be conquered in order for the North to claim victory and compel the rebellious states to return to the Union. A tie or a stalemate would amount to a Southern victory because the Confederacy and slavery would be preserved. The Union, therefore, had to go on the strategic and tactical offensive, for every day of inaction was a minor victory for the Confederates (a fact that too many Union generals failed to comprehend). Offensive warfare consumes more resources than defensive warfare. In addition, widespread use of new weaponry—rifles, rifled artillery, repeating weapons, deadly Minié balls, and breechloaders instead of muzzleloaders—gave the tactical advantage to the defense in the Civil War.

The Confederacy’s scarcity of manpower also militated in favor of staying on the strategic and tactical defensive. Had the South done so, making the North pay a heavy price for going on the offensive, it might have undermined Northern morale and ultimately Lincoln himself. Davis, Lee, and other rebel leaders always knew that the 1864 presidential election in the North would be critical to their success, but they pursued a costly offensive strategy that had ended the South’s prospects for military victory (or even stalemate) by the time Lincoln faced the voters.

If Lincoln had lost the 1864 election to a Democrat, especially George McClellan, the Confederacy likely could have obtained a truce, the preservation of slavery, and perhaps even independence, at least for portions of the South. McClellan had demonstrated his extreme reluctance to engage in the offensive warfare necessary for a Union victory and had shown great concern for Southerners’ property rights in their slaves. The possibility of a Democratic victory in 1864 was by no means far-fetched. Until the end of that summer, Lincoln, like nearly everyone else, thought he was going to lose. Had the South fought more wisely, it might have so demoralized the voters of the North—who were already divided over controversial issues like emancipation, the draft, and civil liberties—that they would have given up on the war and Lincoln.

The primary author of the South’s imprudently aggressive approach to the war was, of course, Robert E. Lee. Though the Myth of the Lost Cause-makers insist he was one of the greatest generals of all time, Lee’s actual record left much to be desired. First, he was a one-theater general apparently more concerned with the outcome in Virginia than in the Confederacy as a whole. He consistently refused to send reinforcements to other theaters and harmfully delayed them on the one occasion when he was ordered to relinquish some troops. Again and again, his actions indicated that he did not know or care what was happening outside his theater. For example, when he initiated the Maryland (Antietam) campaign of 1862, he advised Davis to protect Richmond with reinforcements from the Middle Theater, where rebels at the time were outnumbered three to one.

Second, Lee was too aggressive—both strategically and tactically. His Antietam and Gettysburg campaigns resulted in about forty thousand casualties the South could not afford, including the loss of experienced and talented veterans. Gettysburg also represented lost opportunities in other theaters because Lee kept his whole army intact in the East to invade Pennsylvania. Again and again, Lee launched frontal assaults that decimated his troops—Mechanicsville, Malvern Hill, Antietam (counterattacks), Chancellorsville (after Jackson’s flanking assault), the second and third days at Gettysburg, the Wilderness, and Fort Stedman at the end of the war. Lee’s losing, one-theater army incurred an astounding 209,000 casualties—more than the South could afford and fifty-five thousand more than Grant’s five winning armies suffered in three theaters. Lee’s other weaknesses included poor orders, failure to control the battlefield, and deliberately inadequate staff.

Realizing that Lee was in need of exculpation, his advocates decided to make James Longstreet their scapegoat. They argued that Gettysburg cost Lee the war and that Longstreet was responsible for that loss. Gettysburg alone did not cost the war, and Longstreet played a relatively minor role in Lee’s defeat there. Lee should have sought a defensive battle instead of attacking an entrenched foe. Lee’s major errors in the Gettysburg campaign were his vague orders allowing Jeb Stuart to roam the countryside when Lee needed his scouting and screening abilities, his failure to mandate taking the high ground when he had the numerical advantage on the first day of the battle, his frontal assaults (against Longstreet’s advice) on the second and third days, his failure on all three days to exercise battlefield control, and his failure to coordinate actions of his army’s three corps, which made three uncoordinated attacks over the last twenty-four hours of the battle. Longstreet’s supposedly delayed attack on Day Two (when Lee personally failed to adequately reinforce the attack) pales alongside Lee’s performance as the cause for Confederate defeat at Gettysburg.

Since Grant ultimately defeated Lee, adherents of the Myth of the Lost Cause had to denigrate Grant in order to exalt Lee. They attacked the Union commander as a drunk and a butcher who won only by brute force. There is little evidence that Grant did much drinking in the Civil War and none that it affected his performance. The “butcher” epithet implied that he heedlessly sacrificed his own men in irresponsible attacks on the enemy. As the earlier casualty tables show, Grant’s armies incurred a total of 154,000 casualties in three theaters while imposing 191,000 casualties on their opponents. Recent historians who have closely examined both Lee’s and Grant’s records and casualties have concluded that if there was a Civil War butcher, it was not Grant.

Anyone contending that Grant won solely by brute force has failed to study his victories at Forts Henry and Donelson, Shiloh, Vicksburg, and Chattanooga. His brilliant Vicksburg campaign continues to be studied around the world because of the deception, celebrity, and concentration of force with which he baffled and defeated his opponents. The only three armies that surrendered between Sumter and Appomattox all surrendered to Grant. He was clearly the best general of the Civil War and one of the greatest in American history.

The last aspect of the Myth of the Lost Cause is that the North won by waging “total war.” This allegation fails to distinguish between “hard war,” which involves a destruction of enemy armies and enemy property of all sorts, and “total war,” which additionally involves the deliberate and systematic killing and rape of civilians. Total war was often waged long before the Civil War and was waged again in the twentieth century. The Civil War, however, which saw some localized and vicious guerilla warfare, was not a “total war” on the part of anyone—certainly not the Union.

The Myth of the Lost Cause, then, is a tangle of falsehoods. It should no longer play a significant role in the historiography and Americans’ understanding of the Civil War.

This article is part of our extensive collection of articles on the Antebellum Period. Click here to see our comprehensive article on the Antebellum Period.

Would you like to learn the complete history of the Civil War? Click here for our podcast series Key Battles of the Civil War

Cite This Article

"Myth of the Lost Cause-America’s Most Successful Propaganda Campaign" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

July 25, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/myth-of-the-lost-cause>

More Citation Information.