The following article on Russian and Japanese conflict before Pearl Harbor is an excerpt from John Koster’s Operation Snow: How a Soviet Mole in FDR’s White House Triggered Pearl Harbor. Using recently declassified evidence from U.S. archives and newly translated sources from Japan and Russia, it presents new theories on the causes of the Pearl Harbor attack. It is available to order now at Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

Japan had been a threat to eastern Russia since its startling victory in the Russo-Japanese War, and Britain and the United States had nurtured the rise of Japan as a counterweight to Russia. Stalin might have been paranoid, but by mid-1939 Japan indeed posed an existential threat to the Soviet Union.

Japan’s military forces, which sometimes operated almost autonomously from the Diet in Tokyo, were polarized into two hostile factions. Strike North, dominated by the Chosu clan from Honshu, the largest Japanese island, and in control of the Imperial Army, saw Russia as Japan’s natural enemy. They prepared for war on the Asian continent. Strike South, dominated by the Satsuma clan from Kyushu, the big southern island and the wellspring of Japanese culture, controlled the Imperial Navy and saw the colonial powers of Britain, France, and the Netherlands as the enemy. They prepared for war in the Pacific. All Japanese sentimentally regarded their nation, the only real industrial power in Asia and possessor of the world’s third largest Navy, as the defender of “colored” people everywhere. The Japanese, in fact, had attempted to insert a clause into the charter of the League of Nations recognizing the equality of all races but were rebuffed by the British.

Russian and Japanese Conflict Before Pearl Harbor: The Early 20th Century

Whatever their racial sentiments, Britain and the United States did not want Russia in the Pacific, and they supported Japan’s development into a modern military power. In 1902, with an eye on Germany, a potential Russian ally, and its perennial rival France, Britain entered a treaty with Japan promising its assistance should the Japanese find themselves at war with more than one power. In the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905, Japan enjoyed diplomatic support from Britain and financial support from the Jewish-American banker Jacob Schiff. Outraged at the tsar’s failure to act when dozens of Jews were brutally murdered in Russia, Schiff floated a loan that helped Japan prosecute the war to a successful conclusion. Theodore Roosevelt, an outspoken admirer of Japan, gave copies of Bushido, Inazo Nitobe’s interpretation of the samurai code of chivalry, to his friends. Nobody told Roosevelt that Nitobe, a Christian convert married to an American woman who stuffed their house with garish Victorian furniture, had offered up a rather prettified version of bushido, the way of the warrior. Roosevelt knew less about the Japanese than he thought he did, but he did understand that they could be dangerous to cross—a lesson that his successor and cousin, Franklin, would learn the hard way.

Theodore Roosevelt had less regard for Korea, a country which he saw as incapable of self-government. In 1905, his secretary of war, William Howard Taft, reached an understanding with the prime minister of Japan, Taro Katsura—the so-called Taft-Katsura Agreement, described in a secret and informal memorandum that did not become public until 1924. In return for a free hand in the Philippines, America acceded to Japan’s domination of Korea. The United States turned the Philippines into a plantation while Japan attempted to absorb Korea into its empire. Though the Japanese gave the Koreans their first public schools, banks, and railroads, they earned a reputation for extreme cultural arrogance and brutality, employing rape as a form of crowd control.

Russia’s defeat to Japan in 1905 touched off the discontent with the tsar’s government that set Russia on the road to revolution. The valor and discipline of the victorious Japanese soldiers, on the other hand, had impressed Western observers, Theodore Roosevelt among them. As he guided the belligerents to peace at Portsmouth, New Hampshire, the president sought to check the rising sun of Japanese power. The Treaty of Portsmouth, which ended the Russo-Japanese War and earned Roosevelt a Nobel Peace Prize, provoked a furious reaction in Japan. Convinced that they had been swindled, Japanese mobs burned thirteen Christian churches and every police station in Tokyo. The delegates who signed the treaty were gently told once they got home that they might want to commit suicide because of their disgrace.

In America, sentiment began to turn against the Japanese, particularly in the organized labor movement on the west coast and among the politicians who needed its support. After the San Francisco earthquake of 1906, Japanese, Chinese, and Korean children were removed from their neighborhood schools and concentrated in a single segregated school. Japanese-Americans and the Imperial Japanese government were outraged. Faced with a recalcitrant school board in San Francisco, President Roosevelt came up with the Gentlemen’s Agreement between the United

States and Japan. According to this informal understanding, the U.S. would not enact restrictions on Japanese immigration (as it had done with Chinese immigration in the 1880s), and San Francisco would end its segregation of Asian students. In return, Japan would on its own halt the immigration of its nationals to the United States. The Japanese glumly swallowed the insult and turned their attention to consolidating their hold on Korea.

In 1909, the former Japanese prime minister and resident general of Korea, Hirobumi Ito, who had demanded concessions from Korea at gunpoint but stopped short of outright annexation, was assassinated by a Korean patriot gunman in Manchuria, then controlled by tsarist Russia. Japan responded by annexing Korea the following year and launching a new crackdown.

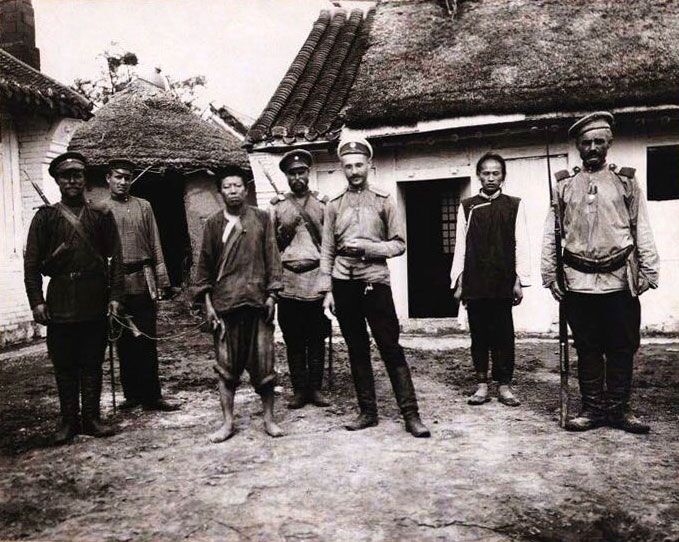

During World War I, the Japanese honored their treaty with Britain by mopping up German possessions in China. The Germans, whose Kaiser Wilhelm II invented the threat of the “Yellow Peril,” admitted that they were treated decently once they surrendered, and some opened businesses in Japan. The Japanese built 123 merchant ships for Britain in shipyards safe from predatory German U-boats, and they sent their Naval forces to the Mediterranean, where a German U-boat torpedoed a Japanese corvette escorting a British convoy, killing seventy-seven Japanese sailors. The Japanese also rescued Armenian and Greek fugitives from the war that started when the Greeks and Turks redressed their postwar borders with reciprocal massacres. Perhaps more to the point, the Japanese sent troops to fight the Bolsheviks for Siberia.

On March 1, 1919, President Woodrow Wilson’s “Fourteen Points” touched off a peaceful demonstration of Koreans inspired by Wilson’s principle of self-determination for all nations. When Korean hoodlums on the fringe of the demonstration robbed a few shops and killed a few Japanese, the Japanese unleashed the Korean National Police—a mixed force of Japanese and Koreans—and Japanese troops, who broke up the demonstrations with gunfire, public rapes of respectable girls, and prolonged floggings of men and women alike. Sumil—March 1—became the black holiday of Korean patriots around the world and marked a watershed. Before the Sumil riots, the enormous technical and education improvements that Japan had brought to Korea made cooperation with Japan a respectable option. After Sumil, most Koreans of education and spirit became bitterly anti-Japanese. The Americans, despite protests from outraged missionaries, did nothing. The Russian threat in the Pacific—a threat that the Bolshevik revolution had intensified—kept the United States content to abide by the still-secret Taft-Katsura Agreement.

Russian and Japanese Conflict Before Pearl Harbor: The 20s

The Anglo-Japanese Alliance was up for renewal in 1922. Under pressure from the U.S. and Canada, Britain let the treaty lapse, casting its lot in the Pacific with the United States. The Washington Naval Conference, which concluded in February of that year, attempted to limit the buildup of the Japanese Naval forces. The conference limited Japan to three battleships for every five built by Britain or the United States—another insult as far as the Japanese were concerned. The Japanese compensated by building more aircraft carriers, a British innovation from World War I not yet recognized as the future replacement of the armored battleship as the most important combat vessel.

Two years after the scrapping of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance, the United States revised its immigration laws to permit exactly one hundred immigrants per year from the empire of Japan to America. Some Japanese were so outraged that they threatened to commit hara-kiri on the steps of the American embassy. The Smoot-Hawley Tariff followed in 1930, raising import duties to 50 percent and inflicting a terrible blow to Japan’s economy.

The Japanese concocted a pretext to seize Chinese-ruled Manchuria, which was rich in raw materials. The Chinese responded with a boycott of Japanese goods and attacks on Japanese businesses. War broke out in 1932, punctuated by the brutal aerial bombing of a civilian slum in Shanghai that killed about a hundred helpless Chinese civilians. At the ensuing peace celebration, a Korean patriot named Yoon Bong-Gil threw a bomb into the Japanese reviewing stand, killing two Japanese generals. Future ambassador to the United States Kichisaburo Nomura lost an eye in the attack, and the future foreign minister Mamoru Shigemitsu lost a leg.

The first battle of Shanghai was followed five years later by a more devastating conflict, the Second Sino-Japanese War. At the start of the second battle of Shanghai, in 1937, Chiang Kai-shek’s air force bombed its own city “by accident”—or to recapture the American and European sympathy aroused by the genuine Japanese bombing in 1932. American observers were startled to see how poorly the Chinese defended themselves. Those Americans who tried to assist the Chinese discovered to their dismay that the whole country seemed to operate on the basis of bribery. Chinese generals expected bribes before they would accept American donations of equipment. Chinese field commanders sometimes ran out on their men on the eve of battle. The Japanese, by contrast, fought with incredible courage and immense energy, but they also committed atrocities at Nanking and elsewhere that horrified even their most ardent admirers. The thousands of Japanese battlefield executions with bayonets and swords and the hundreds of rapes were appalling enough, even before China’s friends exaggerated them far beyond reality. The departure of Chiang Kai-shek and his deputy commander, Tang Sheng-chih, before the battle of Nanking was less widely publicized.

Americans, for the most part, were more upset by the Japanese bombing and strafing of the U.S. gunboat Panay on the Yangtze River, which left three sailors dead and twenty seriously wounded, than they were by the Rape of Nanking. The Japanese apologized for bombing the Panay and sent money to the families. Japanese women chopped off their hair and sent it to the American families to show their grief. The Americans rolled over and went back to sleep. In Too Hot to Handle, a Hollywood movie made the next year, the war in China is treated as a joke. Clark Gable and Leo Carillo, playing news cameramen, lose footage of a mistaken Japanese strafing, so they set up a fake strafing with a kite as a Japanese biplane—just for laughs. The Chinese weren’t laughing.

To the Soviets, the Rape of Nanking, with forty-two thousand Chinese dead, was insignificant compared with Stalin’s purges, and the Russians had always hated Asians in any case. What worried the Soviets was a clash with the Japanese along the Khalkha River in the disputed border region between Mongolia and Manchuria. It was this incident that inspired the NKVD’s frantic desire for a war between the United States and Japan.

This article on Russian and Japanese conflict before Pearl Harbor is part of our larger selection of posts about the Pearl Harbor attack. To learn more, click here for our comprehensive guide to Pearl Harbor.

This article on Russian and Japanese conflict before Pearl Harbor is from the book Operation Snow: How a Soviet Mole in FDR’s White House Triggered Pearl Harbor © 2012 by John Koster. Please use this data for any reference citations. To order this book, please visit its online sales page at Amazon or Barnes & Noble.

You can also buy the book by clicking on the buttons to the left.

Cite This Article

"Russian and Japanese Conflict Before Pearl Harbor" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

July 27, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/russian-and-japanese-conflict-before-pearl-harbor>

More Citation Information.