Thomas Stonewall Jackson was an orphan. His father died when he was two, after having frittered away his money on cards and failed investments, which forced the family to sell their home. Jackson’s mother, known for her good looks and high character, died when he was seven. She left a lasting imprint on the boy, even though Jackson had already been sent to board with his uncle Cummins Jackson at Jackson’s Mill in northwestern Virginia.

Jackson read from an early age. He read the Bible and heroic tales of military history, especially the history of the American War of Independence. But his formal education was necessarily spotty because he had to work. He nevertheless still found plenty of time for fishing, hunting, and riding.

He also taught a young slave to read. There weren’t many slaves in mountainous northwestern Virginia, but Jackson, like everyone else, took slavery for granted and was friendly with such slaves as worked at the Mill. They certainly weren’t “property” to Jackson in the sense of a saddle or a mare; they were people and weren’t to be subjected to the whip or a beating. Indeed, they were friends with young master Jackson. Some of Jackson’s own people had come to colonial America as indentured servants. The slaves were in more extended bondage, their class was different in kind and degree from the Scotch-Irish Jacksons, but he felt there was plenty of commonalities too.

As a boy he was handsome, quiet, honest, and a trifle awkward. He knew he was lacking in the refinements that make a great man and he was determined to change that. Jackson was driven, all his life, by the idea of self-improvement, of overcoming circumstances through sheer focus, concentration, and will. There was no school at Jackson’s Mill, but Jackson convinced his uncle to create one, and when that didn’t last, he enrolled in another school in nearby Weston for impoverished boys. Finally, Colonel Alexander Withers took him in and agreed to be his tutor. The Colonel was impressed by young Jackson, his transparently good character and his dogged determination to learn. Jackson was also sincerely religious and that rare sort of boy who sat up tall to listen to sermons.

Reliability and durability shown out of Jackson; he was only seventeen years old when he was appointed as a constable of Lewis County, which had him tracking down deadbeat debtors. He also stood in well enough stead that he was one of two county finalists for an appointment at West Point. He lost, but when the winner turned back home after one day at the Point, Jackson worked hard to be nominated as his replacement. When the obvious was pointed out to him—that his schooling was hardly such as would make him likely to pass West Point’s entrance examination, let alone survive the demanding curriculum—Jackson replied: “I know that I shall have the application necessary to succeed. I hope that I have the capacity. At least I am determined to try.”

Carrying a packet of recommendations, Jackson traveled hard to reach Washington and win the nomination from his Congressman Samuel Hays. He arrived, mud-spattered, in the congressman’s office without an appointment (Hays was not even aware his previous nominee to West Point had resigned until Jackson presented him with the letter). A quick interview convinced Congressman Hays of Jackson’s fitness and he recommended him for his “manly appearance… good moral character… (and, ahem,] improvable mind.” The eighteen-year-old Jackson had won his appointment to West Point—assuming he could pass the entrance examination; and for that, he crammed, as only a man of Jackson’s tenacity could. He had failed his examinations at home; he passed them at the Point—barely, but he had done it.

From West Point to Mexico

Jackson was determined to succeed. While other cadets slept, he continued studying by the light of coal-fire in the grate. He was already renowned as an eccentric, a young man tormented by dyspepsia, socially and physically awkward (though he kept a notebook of self-improving maxims). He confided in few, was quiet but courteous, and no one worked harder or from higher principles of conduct. Fellow cadet Ulysses Grant recalled that “He had so much courage and energy, worked so hard, and governed his life by a discipline so stern.” An artillery officer losing patience with Jackson’s ungainliness at a cannon, rebuked him, cursing, only to be cut short when he saw Jackson’s face, dripping sweat. It “revealed,” he wrote, “the soul-touching patience and suffering of the ‘Ecce Homo.’ No anger, no impatience, only sorrow and suffering.”‘ It was hard not to give Jackson his due.

Jackson struggled through the academic rigors of West Point, but kept advancing relentlessly up the ranks of cadets. Every final examination was a torture for him as he went sweating up to the blackboard, a smile creasing his face when his power of concentration paid off, he chalked the answer down and could relax, at least momentarily. He was gaining confidence too. He told a cousin back home: “I tell you I had to work hard___I am going to make a man of myself if I live. I can do anything I

will to do.”G He graduated seventeenth in his class, and the joke was, if they’d had another year, Jackson would have driven his way to number one.

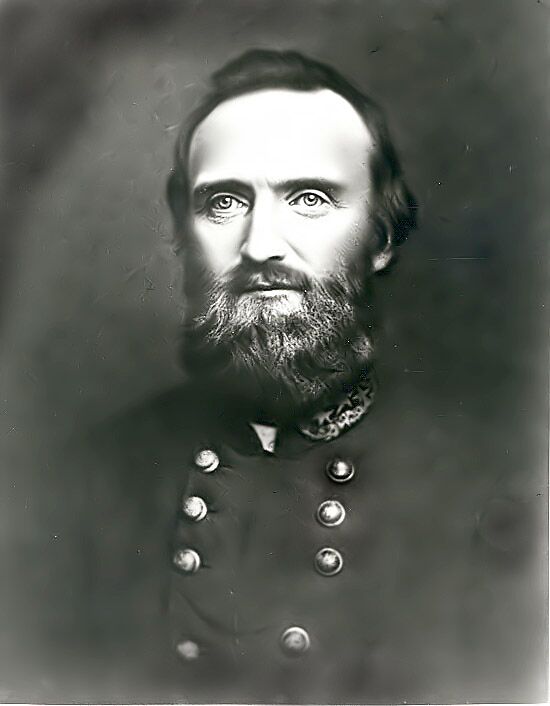

Jackson’s class, the class of 1846, graduated directly into the Mexican War; and Jackson, the newly commissioned lieutenant was now an erect six-footer, handsome, stalwart, with unwavering grey-blue eyes. After arriving in Mexico, he met Second Lieutenant D. H. Hill, West Point class of 1842. Hill had already seen combat. Jackson told him, “I really envy

you men who have been in action___I should like to be in one battle.” As Hill recalled, “His face lighted up and his eyes sparkled when he spoke, and the shy, hesitating manner gave way to the frank enthusiasm of a soldier.”

A professional soldier is not what Jackson had aspired to become. His West Point education was a means to an end, the end of helping him become a better man, a respected professional. But the training and opportunity bit into him. In Mexico, he distinguished himself from his first taste of combat at Vera Cruz. Manning a battery of artillery, one observer noted that Jackson “was as calm in the midst of a hurricane of bullets as though he were on dress parade at West Point.”

Later, as an artillery officer under Captain John Magruder, Jackson fought his batteries on the approaches to Mexico City. Repeatedly under fire, he again never showed a hint of fear, whether men toppled beside him, caissons were smashed before him, or even as a cannonball plowed directly between his legs. At one point during the assault on Chapulte-pec, Jackson walked calmly in front of his batteries, enemy lead bursting all around him, reassuring his men, “See, there is no danger. I am not hit!” As Jackson later confessed, it was the only lie he could remember telling— but at least it was in the line of duty and in the service of his men.

In a letter to his sister, six weeks later, he noted, “I have been exposed to many dangers in the battles of this valley but have escaped unhurt. I was once reported killed and nothing but the strong and powerful hand of Almighty God could have brought me through unhurt. Imagine, for instance, my situation at Chapultepec, within full range, and in a road which was swept with grape and canister, and at the same time thousands of muskets from the castle itself above pouring down like hail upon you.” A hot time, indeed, but Jackson had not wavered.

Though he had labored at French at West Point, Jackson taught himself Spanish to a fair degree of fluency; admired Mexican cathedrals; actually came out of his shell to attend balls with sseniority spent several days in a monastery and interviewed the archbishop of Mexico City as part of an earnest consideration of the Catholic Church, before deciding that he sought a simpler Christianity; and developed a passion for fruit. As part of the victorious army now occupying Mexico, Jackson actually enjoyed himself. For him, Spanish always remained the language of romance.

“Tom Fool” Jackson

Returning home on leave, Jackson was prescient: “If there is another war, I will soon be a general. If peace follows, I will never be anything but Tom Jackson.”,D Tom Jackson, however, was an interesting customer in his own right. Jackson’s eccentricities—he was a food faddist, devoted to water cures, stale bread (he timed its aging with a watch), and an idiosyncratic exercise program, among other things—became legend among his compatriots, but there was still something winsome about his sincerity. He continued his studies in religion, was baptized (in the Episcopal Church, but only after negotiating with the priest to ensure that he was still free to pitch his Christian tent in whatever denomination he eventually settled on), and continued to enjoy an active social life in the peacetime army. He also continued his self-education by becoming a patron of New York City bookstores, focusing mainly on volumes of history. His actual military duties were slight, and after a tedious and unhappy time posted to Florida, he won an appointment as an instructor at the Virginia Military Institute in Lexington, Virginia.

When a friend asked how he would manage to teach college-level courses to the cadets, given his own academic struggles, Jackson replied: “I can always keep a day or two ahead of the class. I can do whatever I will to do.” That will required painstakingly memorizing his lectures, spending his evenings, when his eyes were too tired to read, staring at a wall, reciting the lectures in his head. In the classroom, he was unable to deviate from their literal recitation. An unexpected question could set him repeating his lecture from the beginning. The cadets nicknamed him “Tom Fool” Jackson, regarding him as a continual odd duck and an occasional martinet (though they took advantage of his poor hearing—the price of his being a former artillery officer). But they also knew of his reputation, of how in Mexico he had been among the bravest of the brave, and they caught glimpses of it when he was outside the classroom, acting as an instructor of artillery. He was not meant to be a teacher; he was meant to be a soldier.

It was in Lexington that Stonewall Jackson finally settled on the Presbyterian Church as his spiritual home. It was, naturally, not chosen on a whim but only after continual study of religious doctrine and probing sessions with the local Presbyterian minister. Dr. William Spottswood White. But once in, he was a fiercely committed adherent, albeit one who, with typical eccentricity, more often than not fell asleep in church. Asleep or awake, he lived his life in a state of silent prayer.

Stonewall Jackson prayed for his cadets before every lecture at VMI. His piety expressed itself, too, in his acting as devoted co-founder, sponsor, and teacher of a black Sunday school that not only taught religion but skirted the law by teaching slaves and their children to read and write. If Stonewall Jackson bored the cadets, he found a more receptive audience here. His classroom discipline was strict, but he was regarded, in the words of the Reverend White, as “emphatically the black man’s friend.” He was so much the black man’s friend that two of his slave-students asked him to buy them. So Jackson became the slaveholder of Albert, a handyman who eventually earned enough money to buy his freedom, and Amy, a housekeeper. Through marriage he gained another slave, Hetty and her two sons (whom Stonewall Jackson taught to read). He also took in a slave who had been orphaned, a girl named Emma.

Stonewall Jackson’s religion brought him romance as well. In 1853 he married Elinor Junkin, daughter of the Reverend Dr. George Junkin, a Presbyterian divine who was president of Washington College, adjacent to VMI. Elinor Stonewall Jackson died only fifteen months later, shortly after giving birth to a stillborn son. In 1857, Stonewall Jackson married again, this time to Mary Anna Morrison (she went by Anna), another Presbyterian minister’s daughter. Her father was Dr. Robert Hall Morrison, the first president of Davidson College, and she was a sister-in-law to his old Mexican War colleague, fellow postwar professor, and friend D. H. Hill. Their first child died, but Anna lived, and Stonewall Jackson was utterly devoted to her. She bore him another child, a daughter, in 1862, who survived. Jackson always loved children. With them his awkwardness and reserve dropped away and he happily joined in their games and adventures. But he knew his own daughter for less than a year before his own tragic death.

The reluctant secessionist

Stonewall Jackson was a Democrat and a states’ rights man, but like most northwestern Virginians, many of his neighbors in the Shenandoah Valley, and Dr. Junkin (a native Pennsylvanian who declared “I would not dissolve this union if the people should make the devil President”), he was also a Unionist. As for slaver}’, his wife Anna said, after the War, that he would have preferred “to see the negroes free, but he believed that the Bible taught that slavery was sanctioned by the Creator himself, who maketh men to differ, and instituted laws for the bond and the free. He therefore accepted slavery, as it existed in the Southern States not as a thing desirable in itself, but as allowed by Providence for ends it was not his business to determine.”

Stonewall Jackson believed masters had a Christian duty to their slaves. His slaves were part of the family’s own daily religious life of Bible readings, prayer, church, and Sunday school. He disliked abolitionists, as agitators attempting to drive the nation into division and war.prayer, church, and Sunday school. He disliked abolitionists, as agitators attempting to drive the nation into division and war.He was present, with a detachment of VMI cadets, when one of the most dangerous—indeed, mad—abolitionists, John Brown, was hanged at Charles Town, Virginia. Stonewall Jackson and the cadets were there to keep the peace. For Virginians like Stonewall Jackson, all the South wanted was a peaceful abidance by the Constitution. If the North, through men like John Brown or Abraham Lincoln tried to violate Southern rights, to impose their doctrines by armed force, only then would secession be justifiable.

Until then, Jackson’s position was to support the Union and “to see every honorable means used for peace, and I believe that Providence will bless us with the fruits of peace___But if after we have done all that we can do for an honorable preservation of the Union, there shall be a determination on the part of the Free States to deprive us of our right which is the fair interpretation of the Constitution, as already decided by the Supreme Court, guarantees to us, I am in favor of secession.” But it was more than the defense of slavery that Jackson saw as Southern rights; it was a constitutional system that granted the states extensive sovereign powers that the Federal government was not to trifle with.

As Stonewall Jackson’s widow remembered, he “would never have fought for the sole object of perpetuating slavery. It was for her constitutional rights that the South resisted the North, and slavery was only comprehended among those rights.”‘0 What was not comprehended among the rights of the Federal government was the right to invade sovereign states that had joined the Union and now had decided to leave it of their own free will, as decided by their state legislatures. Virginia was, initially, not among the seceding states. But when Lincoln called upon Virginia to raise troops to subjugate its fellow Southern states, the die was cast. Virginia would do no such thing. To do so would be to support Northern tyranny against the South.

Jackson took the long view. He had supported the Union when in good conscience he could. But the Federal government was not God. “Why should Christians be disturbed about the dissolution of the Union? It can only come with God’s permission.” The Federal government was an institution created by the people of the sovereign states. The people of the sovereign states could change their mind, and the Federal government had no divine mandate forcibly to tell them otherwise.

Jackson’s battles

As trained soldiers, Jackson and his cadets were valuable men to the new Confederacy; their task: train Virginia’s volunteers into a semblance of an army. Stonewall Jackson’s duties first brought him to Richmond, and then to Harpers Ferry as a Colonel of Virginia volunteers. The Stonewall Jackson legend began almost immediately. He was taciturn, disciplined, mysterious, devoted to duty, eccentric, and oblivious of appearances. He wore a cadet cap down close over his brow. His horse, “Little Sorrell,” originally bought for his wife, looked almost like a pony beneath the six-foot tall Jackson. Among the units trained by Jackson was the First Virginia Brigade, drawn from the Valley, which became known as “the Stonewall Brigade.”

From the start Stonewall Jackson had a strategic and tactical rapport with Jefferson Davis’s top military adviser, Robert E. Lee. Jackson believed that “we must give them [the enemy] no time to think. We must bewilder them and keep them bewildered. Our fighting must be sharp, impetuous, continuous. We cannot stand a long war.”10 Lee agreed, and he shared Jackson’s desire to take the war to the enemy. But the gentlemanly Episcopalian Lee drew a firmer line on waging war exclusively against the Union army than the stern Presbyterian Stonewall Jackson did, at least in Stonewall Jackson’s strategic vision for the war. Jackson saw the greatest mercy—and the greatest opportunity for Southern victory—in swift, crushing counterstrok.es that would shock the North into letting the South go free.

Stonewall Jackson told General G. W. Smith that “We ought to invade their country now [the fall of 1861], and not wait for them to make the necessary preparations to invade ours.” Stonewall Jackson’s plan was to concentrate Confederate forces to cross the Potomac, seize Baltimore, bring Maryland to the side of the South, force the Federal government from Washington, attack McClellan’s army “if it came out against us in open country, destroy industrial establishments wherever we found them, break up the lines of interior commercial intercourse, close the coal mines, seize, and if necessary destroy the manufactories and commerce of Philadelphia, and of other large cities within our reach.” The Confederate army would “subsist mainly on the country we traverse” and make “unrelenting war” amidst Northern homes, forcing “the people of the North to understand what it will cost them to hold the South in the Union at bayonet’s point.”

There is no doubt that to some degree Stonewall Jackson was right. In this strategy lay the Confederacy’s greatest chance for victory, but it was utterly opposed to the vision of Jefferson Davis, which was defensive. Davis certainly understood the military merits of concentration of force but believed he needed to defend the borders of the Confederacy. Even more important, Davis believed he must maintain the South on the moral high ground. The North was the aggressor and he did not want to muddy appearances in the fall of 1861. Whether Stonewall Jackson’s offensive could have been conducted in a way that would have fallen within the parameters of just war, as Lee and Davis thought of it, is debatable. But given Jackson’s unbending devotion to orders, chances are that some such compromise could have been made: an invasion made in defense of the South and in a war that hit military targets (railroads, munitions, telegraph wires) while sparing civilians.

In the event, Lee and Jackson’s first point of agreement was that Harpers Ferry should be held. The commander on the scene, however, was that brilliant artist of the tactical retreat, General Joseph E. Johnston, who never met a position from which it was not advantageous to fall back. Still Stonewall Jackson’s men, in a defensive sally, did get their first taste of battle, and Jackson was promoted to brigadier general in the Confederate army.

“Tom Fool” Jackson becomes Stonewall Jackson

Jackson who was a hypochondriac in peace (driven by intestinal trouble that once caused him to remark that “if a man could be driven to suicide by any cause, it might be from dyspepsia”) was a veritable titan in war. At First Manassas when General Bernard Bee rode by exclaiming, “They are beating us back! They are beating us back!” Jackson calmly replied, “Then, sir, we will give them the bayonet.” He was similarly unruffled when a bullet struck a finger on his left hand. Bee used Jackson’s example to reform his men: “Look, men, there stands Jackson like a stone wall! Rally ’round the Virginians.”

At the battle’s height, as Stonewall’s men braced for a Union charge, a Confederate officer rode up to Jackson and said: “General the day is going against us.”

“If you think so, sir, you had better not say anything about it.”

He counseled his own men: “Reserve your fire till they come within fifty yards, then fire and give them the bayonet. When you charge, yell like furies.” Stonewall Jackson’s men helped turn the tide. As the Federals broke and ran, Stonewall Jackson said: “Give me ten thousand men and I will be in Washington tomorrow morning.”20 Had they been, Stonewall Jackson might now be remembered as the founder of his country.

As it was, he deepened his men’s confidence that he was a cool-headed general who knew how to smite the enemy. With victory won, Stonewall Jackson turned to another important matter that had been preying on his conscience. He sat down and wrote a letter to the Reverend William S. White: “In my tent last night, after a fatiguing day’s service, I remembered that I had failed to send you my contribution to our colored Sunday School. Enclosed you will find my check for that object, which please acknowledge at your earliest convenience, and oblige. Yours faithfully, T. J. Jackson.”‘

The hero of the valley

In October 1861, Jackson was promoted to major general and given command of Confederate forces in the Shenandoah Valley. Jackson astonished his own troops, and the Federals, by insisting on a winter campaign. On 1 January 1862, Jackson drove his men on a forty-mile forced march through snow and ice to fight the Yankees at the town of Bath. But the Federals withdrew. Jackson pressed on, despite the frigid weather, pushing his men on to the town of Romney. Jackson’s cavalry, under the command of the dashing Ashby Turner, discovered the Federals had abandoned Romney, fearful that Jackson’s command of perhaps 6,000 frozen, sick, and hungry men, might be too much for the 18,000 Union troops.

Jackson’s victory at Romney, however, was not a happy one. Officers complained to Richmond that they were holding a frozen, strategically unimportant waste, at the orders of a madman. Their lobbying Richmond—even President Davis—led to orders being handed Jackson to withdraw the men. Jackson threatened to resign over this interference with his command. Jackson’s protest had the desired effect—the general who had opposed was transferred. But the Federals returned to Romney and once more threatened the Valley.

To the East, the Confederacy braced for McClellan’s massive march on Richmond. In the Valley, Jackson saw his task as bedeviling a Union foe much superior to his own in numbers. Jackson had no more than 4,000 men. Union General Nathaniel Banks, who was advancing on Winchester, had nearly 40,000. Naturally, Jackson decided to attack. But his carefully laid plans were foiled by junior officers who made mistakes and took the counsel of their fears (something that Jackson famously said one should never do).

Jackson vowed never to risk such errors again by never again having a council of war. Jackson’s plans were now to be known only to Jackson, and to his superior officers, like Lee, from whom he received orders. To the others, his marches and countermarches could seem madness. Confederate General Richard “Dick” Ewell said of Jackson, “I never saw one of Jackson’s couriers approach without expecting an order to assault the North Pole!”

Jackson’s orders were to keep the Federals occupied in the Valley, in particular ,to prevent General Banks from crossing the Blue Ridge Mountains and threaten Joseph E. Johnston, who had troubles enough preparing the defense of Richmond against the combined forces of generals McClellan and McDowell. When Ashby Turner brought Jackson word that Banks was moving out of the Valley to support a giant Federal campaign against Richmond. Jackson marched his men more than forty miles in two days to try to cut him off. He met a portion of Banks’ army at Kernstown. That portion turned out to be bigger than Jackson expected—three times bigger—and the fighting was ferocious. Trusting to Providence, Jackson refused to admit defeat until his men finally admitted it for him. They could not advance; they could, at best, hold their line against the overwhelming Yankee numbers.

It was a tactical defeat, but it proved a strategic victory. The Federal commander believed that Jackson had actually outnumbered him by two to one. That was enough to put the wind-up Lincoln, who feared that while McClellan drilled his men for the great march on Richmond, Jackson might slip through the Valley and attack Washington. Lincoln demanded that Banks be retained as a stopper in the Valley. General Fremont was ordered to the Valley as well, and General McDowell was told to stay put at Manassas, in case Jackson crossed the Blue Ridge himself for a northern thrust. Jackson led the Federals on a merry chase, dodging them (sometimes three separate Union armies) and stinging them at will thanks to the astonishing marches of Jackson’s ”foot cavalry,” which seemed to be one place, then another—and never where one expected (and had reliable reports) that they were. Jackson’s Valley Campaign is a standard military study of tactical genius, and much of Jackson’s reputation rightly rests upon it. General Richard Taylor, who served with Jackson, said that among the hard-marched troopers, “Every man seemed to think he was on a chessboard and Jackson played us to suit his purpose.” So he did, and the short, sharp, shocks that Jackson gave the enemy in the Valley in the spring and early summer of 1862 made him a Confederate a hero. In the scale of Civil War battles, the engagements of the Valley campaign were small-scale affairs. Jackson never had more than 16,000 men but he tied up about 64,000 Union troops. The legend that was begun at Manassas became writ large in the Valley.

Chancellorsville and death

If he was the hero of the Valley, he also participated in the big battles as well: The Seven Days Campaign, Fredericksburg, Second Manassas, and Sharpsburg. But his apotheosis was at Chancellorsville, the most brilliant Confederate victory of the war, its battle plan drawn up by Lee and Jackson over a campfire. Lee was holding back the jaws of a pincer movement. At one end, he had a holding force at Fredericksburg, keeping back a Union host more than twice its size. At the other end, Chancellorsville, Jackson had surprised the Federals, attacked, and driven them to entrench their position. There were about 73,000 of them. Lee and Jackson had about 43,000 men. That night, Lee, in conference with Stonewall Jackson, mused, ”How can we get at those people?” The answer was a bold flanking movement across the front of the Federal line, shielded by forest, to strike at the Federal right.

The conversation has been recorded as going something like this:

“General Jackson, what do you propose to do?”

“Go around here.”

“What do you propose to make this movement with?”

“With my whole corps.”

“What will you leave me?” “The divisions of Anderson and McLaws.”

“Well, go on.”

That was it. The plan was agreed, and near dusk the next day, Jackson’s troops were ready to spring. At 5:15 p.m., General Jackson gave the order.

“Are you ready, General Rodes?” Jackson asked.

“Yes, sir.”

“You can move forward then.”

With a terrifying rebel yell, the Confederates ripped into the Union line and sent the bluecoats fleeing.

“They are running too fast for us,” one Confederate officer remarked to Jackson. “We can’t keep up with them.”

“They never run too fast for me, sir. Press them, press them!”

Press them they did to the point of creating a Federal rout. Jackson intended to press the attack through the night, but scouting ahead of his own lines to see how he could capitalize on his smashing success, Jackson was shot by Confederate soldiers who mistook him and his staff officers for a Federal patrol. Jackson was badly wounded, but no one knew yet that it was mortal.

When Lee was informed of Jackson’s wound, he replied, “Ah, Captain, any victory is dearly bought which deprives us of the services of General Jackson, even for a short time.” Lee wrote to his wounded general, “Could I have directed events, I would have chosen for the good of the country to be disabled in your stead. “ZG To one of the army chaplains. Lee noted that Jackson’s arm had been amputated. “He has lost his left arm, but I have lost my right.” Pneumonia claimed Jackson’s last breath; his last words were: “Let us cross over the river and rest under the shade of the trees.”

The ”great and good” Jackson was gone, and with him, perhaps, went the cause of the Confederacy. Lee certainly thought so. He was said to have remarked after the war, “If I had had Jackson at Gettysburg, I should have won that battle, and a complete victory there would have resulted in the establishment of the independence of the South. If there is one reason why the enigmatic, eccentric Jackson—the “Tom Fool” turned audacious and brilliant Cromwellian warrior—became an icon of the South, a symbol of the Lost Cause second only to Lee, this is why.

Jackson’s piety was admired by most and suspected by a few. But few could doubt that that large, shambling, dusty man with his cadet cap pulled low over his mystic grey-blue eyes, his terse, ever-controlled speech, delivered victories, that he had a measure of strategy and tactics that put him among the greats. Field Marshal Lord Frederick Roberts (“Bobs”), the commander in chief of the British Army at the turn of the century, said of Jackson: “In my opinion Stonewall Jackson was one of the finest natural geniuses the world ever saw. I will go even further than that—as a campaigner in the field he never had a superior. In some respects I doubt whether he had an equal.” In his devotion to duty, Jackson lived his axiom: “You can be whatever you resolve to be.” “Old Jack” set his sights high, and Southerners have looked up to him ever since.

Cite This Article

"Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson (1824-1863)" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

April 29, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/thomas-jonathan-stonewall-jackson-1824-1863>

More Citation Information.