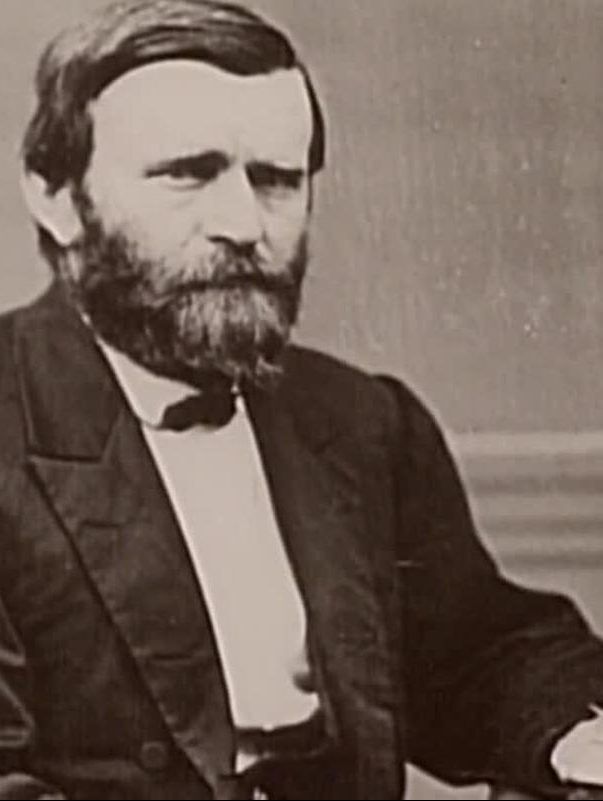

“My family is American, and has been for generations, in all its branches, direct and collateral.” So begin Ulysses S. Grant’s memoirs, and from that beginning, one already gets a good impression of the man, a man who is a prototypical American type: direct, unassuming, sturdy, independent, and practical. There is no preening on aristocratic European origins. No pretense of somehow being related to Richard the Lionhearted. No Southern sense of medieval chivalry and feudalism transported to the landed estates of the cotton kingdom. Ulysses S. Grant was an American; and he, more than anyone else, prevented there being two Americas. It was his implacable will, his stubborn devotion to the cause, his unceasing determination to fight, no matter what the cost, to ultimate victory—and his magnanimity in that victory—that ensured the cause of the Union. Before the war, he was an unlikely hero. But his heroism is a very American story—an Horatio Alger story in Union blue. No less a man than William Tecumseh Sherman thought so: “Each epoch creates its own agents, and General Grant more nearly than any other man impersonated the American character of 1861–5. He will stand, therefore, as the typical hero of the Great Civil War.”

Ulysses S. Grant: a Horse-Loving Boy

He was born Hiram Ulysses Grant in Ohio, a son of a tanner and farmer. While his father tanned hides, his son preferred them on living beasts, on horses, and he became an adept horseman. He hated the stench and blood of the tannery—so much so that in later life his meat had to be blackened free of blood.

Avoiding the tannery, he preferred working on his father’s farm, applying himself to practical, solitary tasks, and leading the plough horses. By the age of fourteen, he was running a livery business, driving horse drawn wagons and carriages for families needing a ride out of town. Getting out of town, and away from the tannery, was a constant desire of his boyhood. In fact, like many boys, he seemed happiest wandering alone outdoors, daydreaming under the sun, lost in his own thoughts (which were not entirely unproductive: he taught himself algebra).

His father, perhaps recognizing that Ulysses would not a tanner be, ensured him a good education and won him a nomination to West Point. For a man like Ulysses S. Grant’s father, successful, self-taught, and with interests in social standing and politics (he was a Whig and opposed slavery), the military academy offered his son a heady combination: prestige, a fine education, a career, and had the added benefit of being free. In his memoirs, Grant records his father’s announcement:

“Ulysses, I believe you are going to receive the appointment.”

“What appointment?” I inquired. “To West Point; I have applied for it.” “But I won’t go,” I said. He said he thought I would, and I thought so too, if he did. I really had no objection to going to West Point, except that I had a very exalted idea of the acquirements necessary to get through. I did not believe I possessed them, and could not bear the idea of failing.

Ulysses S. Grant, then, was not a rebellious teenager in the usual sense. He was honest, modest, quiet, and self-contained, and if his humility made him fearful of West Point, there was one more immediate and important gift the military academy gave him: it was his ticket out of Georgetown, Ohio. “I had always a great desire to travel. I was already the best traveled boy in Georgetown, except for the sons of one man, John Walker, who had emigrated to Texas with his family, and immigrated back as soon as he could get the means to do so.”

West Point gave him another gift: his adult name. Gone, because his nominating congressman had made a mistake, was Hiram. Ulysses (the name he had always used) became his official Christian name, and Simpson (his mother’s maiden name) was suddenly inserted as his middle name. Characteristically, it was an error Ulysses S. Grant never bothered to correct— too shy, and perhaps too pleased at the practical improvement, to do so.

It also won him a new nickname—“Sam” from his new initials U. S., “Uncle Sam” Grant.

He felt no military calling and by his own account was not a studious cadet. He enjoyed mathematics, but otherwise preferred reading novels from the school’s library rather than studying. “I read all of Bulwer’s [Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s novels] then published, [James Fenimore] Cooper’s, [Captain] Marryat’s, [Sir Walter] Scott’s, Washington Irving’s works . . . and many others.” He even hoped that the military academy might be abolished while he was a student (such a motion was being debated before Congress). Nevertheless, he was a quick study and managed to graduate in the middle of his class (and was also known as West Point’s best horseman) in 1843. His shyness, or what his friend and fellow West Pointer James Longstreet called Ulysses S. Grant’s “girlish modesty,” is the reason for Grant’s famous indifference to military dress. Initially, like most young officers, he was eager to display his new uniform. But when a ragged young boy and a dissipated stable hand mocked his appearance, Grant confesses, he gained “a distaste for military uniform that I never recovered from.”

He was sent to Jefferson Barracks, St. Louis, as a lieutenant of infantry where one of his fellow lieutenants (and fellowWest Pointers) was Richard S. Ewell, his senior, who, as he states, “later acquired considerable reputation as a Confederate general during the rebellion. He was a man much esteemed, and deservedly so, in the old army, and proved himself a gallant and efficient officer in two wars—both in my estimation unholy.”

Those two “unholy” wars were the Mexican War and the War for Southern Independence—indeed the two were related. “The occupation, separation, and annexation of Texas,” which set the stage for the Mexican War, was, in Ulysses S. Grant’s view, “a conspiracy to acquire territory out of which slave states might be formed for the American Union.” Moreover, the “Southern rebellion was largely the outgrowth of the Mexican war. Nations, like individuals are punished for their transgressions. We got our punishment in the most sanguinary and expensive war in modern times.”

It is telling, of course, that Ulysses S. Grant thought Southern independence was an “unholy” cause, but its suppression a righteous one—just punishment for the sin of acquiring America’s Western empire. Grant nevertheless participated in the “unholy” war against Mexico because “Experience proves that the man who obstructs a war in which his nation is engaged, no matter whether right or wrong, occupies no enviable place in life or history.”

At War in Mexico

Ulysses S. Grant served under “Old Rough and Ready,” General Zachary Taylor, and got his first taste of combat on 8 May 1846 at Palo Alto. As “a young second-lieutenant who had never heard a hostile gun before,” Grant remembered, “I felt sorry that I had enlisted.” Nevertheless, he acquitted himself well, and no one ever accused Grant of quivering under fire— precisely the opposite; he showed no emotion at all.

Ulysses S. Grant learned more than the blunt task of soldiering through cannon balls and bullets; he learned generalship. Taylor shared Grant’s disdain for the pomp, refinery, and spit and polish of military etiquette, but, as Grant saw, he knew how to get things done. Among other things, “General Taylor was not an officer to trouble the administration much with his demands, but was inclined to do the best he could with the means given him.” If he thought a directive was impossible to achieve he would say so. “If the judgment [of the authorities] was against him he would have gone on and done the best he could with the means at hand without parading his grievance before the public. No soldier could face either danger or responsibility more calmly than he.” What Grant admired in Taylor were the very traits that shone through Grant himself in the Civil War.

Ulysses S. Grant’s coolness under fire was manifest from the start. “There is no great sport in having bullets flying about one in every direction but I find they have less horror when among them than when in anticipation,” he wrote. He had seen violent death, decapitation from a cannon ball, and an officer horribly maimed with his lower jaw torn off. Yet he could still say, “War seems much less horrible to persons engaged in it than to those who read of battles.” Grant knew that fear comes from the imagination; courage comes from a relentless focus on the duty at hand—even in a hail of musketry and cannon.

In August 1846, Ulysses S. Grant was assigned as quartermaster to the Fourth Infantry—a vast job, but one he didn’t want; not because of the pressure of its responsibilities but because it took him out of the firing line. “I respectfully protest against being assigned to a duty which removes me from sharing in the dangers and honors of service with my company at the front. . .” His protest was rejected on the grounds that it was his meritorious conduct and skill that merited him this promotion. Grant was not appeased, venting his frustration by writing on the back of the rejection he had received from Lieutenant Colonel John Garland: “I should be permitted to resign the position of Quartermaster and Commissary. . . . I must and will accompany my regiment in battle.”

Ulysses S. Grant, however, did his duty. General Zachary Taylor needed an energetic young officer to keep his army supplied on its march through Mexico. In “Sam” Grant, he had found his man. Grant had a logistician’s mind. He was methodical, but quick in acquiring and sifting information, and he was diligent. He was also creative: when former Congressman Thomas L. Hamer joined his staff (serendipitously he was the congressman who had appointed Grant to West Point), Grant used the terrain they rode past to pose tactical problems for Hamer, war-gaming their way through the Mexican countryside.

At the battle of Monterrey (21–23 September 1846) Ulysses S. Grant capitalized on his Indian way with horses. As regimental quartermaster he should have had no role in the action, but, “My curiosity got the better of my judgment, and I mounted a horse and rode to the front to see what was going on. I had been there but a short time when an order to charge was given, and lacking the moral courage to return to camp—where I had been ordered to stay—I charged with the regiment. . . . I was, I believe, the only person in the 4th infantry in the charge who was on horseback, The charge was fruitless and costly, with one-third of the men going down as casualties. But though he was mounted, and therefore an easy target, Grant emerged without a scratch.

This was only the beginning. Once engaged in battle in the city Ulysses S. Grant volunteered to ride through the streets of Monterrey, through enemy fire, to reach the division commander and acquire more ammunition for his hard-pressed brigade. He rode like a circus rider, flipping his body to the horse’s side away from the enemy, then throwing himself full in the saddle and dashing to safety.

After Monterrey the American thrust against Mexico shifted from Zachary Taylor to “Old Fuss and Fathers” General Winfield Scott, a military genius who plotted a course from Vera Cruz to Mexico City, following the path of Cortez. On the march and in battle, Ulysses S. Grant did as he did at Monterrey, performing his quartermaster duties, but joining the action whenever he could. As ever, he was stalwart, brave, and enterprising— including, during the fight for Mexico City, talking his way into a church, identifying its belfry as a perfect site from which to strike, rushing off in search of howitzer, finding one, disassembling it, bringing it up to the church belfry, and then reassembling it there to pound the enemy.

Peace But Not Prosperity

With the war won, Ulysses S. Grant’s thoughts turned from battle to the only thought that continually interrupted his concentration on his duty: marriage to his sweetheart Julia Dent. It was a mixed marriage. Grant the Ohioan, whose family had abolitionist sentiments, had conjoined himself to a family of Missouri slave owners. The fathers-in-law of the happy couple despised each other.

Nevertheless, the Grant-Dentmarriage was a success. Ulysses S. Grant relished time with his family, and military assignments that separated him from his wife and their children (of whom there would be four) left him depressed. The peacetime army, with its long, unpredictable postings in remote locations, low pay, and inevitable boredom (Grant went from combat to clerical work) was distasteful to the brave, young West Pointer who had never considered the military his career. The best thing about a West Point education— besides its being free—was that it set one up for remunerative employment as an engineer or a business manager after one’s obligatory service.

Ulysses S. Grant stayed in the army for six years after the Mexican War. They were years of frustration—tedious work punctuated by loneliness—that took him to Detroit, New York, a perilous passage through cholera-ridden Panama, the Oregon Territory, and California. He filled the unforgiving minutes with drinking, moonlighting business ventures (which failed), and reading (Grant was an unusually well-read man who never advertised the fact). When he resigned his commission, he found he could not even afford his passage home to Missouri. In New York, a brother West Pointer and a Southerner (most of Grant’s friends in the army were Southerners), Simon Bolivar Buckner, loaned him the money he needed.

Ulysses S. Grant turned down a position in his father’s leather goods shop in order to become a farmer on sixty acres that had been given Grant by his wife’s father, “Colonel” Frederick Dent, a colonel of the Southern honorific type. Farming suited Grant, and his enterprising nature—necessary given the depressed agricultural market of the time—kept him busy with other businesses as well, among them, supervising slaves on the Dent plantation. He also built a house for his family. He called it Hardscrabble.

As the country slid into an economic depression, Ulysses S. Grant’s circumstances became increasingly precarious; he floundered trying to find work that would keep him solvent. At one point, in an incident that could have come straight from an O. Henry short story, he pawned his watch to buy Christmas presents. In 1860, Grant’s father again offered him a position in his leather goods store, and this time, in desperation, Grant accepted. He moved his family to Galena, Illinois.

He was again a clerk, a job that hadn’t suited him in the army and that suited him no better in peacetime. But if his duties did not engage him, the newspapers did, and so did political talk in the shop. He felt the country dividing, the fault lines separating. He said, “It made my blood run cold to hear friends of mine, Southern men . . . discuss dissolution of the Union as though it were a tariff bill.”

In 1856, he had voted for the Democrat James Buchanan over the Republican John C. Frémont, because, as he said, “I knew Frémont,” but also because, though opposed to slavery, he saw Buchanan as a moderate candidate who could keep the country together. He could not vote in the election of 1860, because he had not been resident long enough in Illinois, but if he could have voted, he would have cast a ballot for the Democrat Stephen Douglas, perhaps on the same grounds.While Ulysses S. Grant’s brother celebrated Lincoln’s victory, Grant himself, having seen war, was gloomy, telling one reveling Republican, “The South will fight.” Later, when another doubted the Southern states’ willingness to secede, arguing that “There’s a great deal of bluster about Southerners, but I don’t think there’s much fight in them,” Grant demurred. “There is a good deal of bluster; that’s a product of their education; but once they get at it they will make a strong fight. You are a great deal like the min one respect—each side underestimates the other and over-estimates itself, which was right enough.

Return to the Colors

When the South seceded, Ulysses S. Grant’s course was clear. He wrote his father, “We are now in the midst of trying times when every one must be for or against his country. . . .Having been educated for such an emergency, at the expense of the Government, I feel that it has upon me superior claims, such claims as no ordinary motives of self-interest can surmount.” His father had given him financial security. But the country was at war, and Grant took up the responsibility of drilling volunteer troops, then working for the governor as mustering officer (though still a civilian), while waiting for an appropriate commission, which the governor finally handed him, making Grant a colonel of Illinois volunteers.

Ulysses S. Grant was not an imposing figure. In fact, he took care not to appear as one, disdaining bluster, pomp, and hard language. (He believed he had never sworn in his life.) But without raising his voice he carried a certitude about him. If Grant gave an order—and his orders were always very clear—he expected it to be done quickly and well. His quiet authority was such that even such an undisciplined mob as the Twenty first Regiment of Illinois Volunteers felt it would be wrong and foolish not to obey.

Ulysses S. Grant’s volunteers (Grant was, ironically, put under the command of John C. Frémont) were sent to subdue rebels in Missouri. It was here that Grant had an epiphany about the nature of combat. His men were moving against a Confederate unit commanded by Colonel Thomas Harris. As they approached the site of Harris’s camp,

. . .my heart kept getting higher and higher until it felt to me as though it was in my throat. I would have given anything then to have been back in Illinois, but I had not the moral courage to halt and consider what to do; I kept right on. . . . The place where Harris had been encamped a few days before was still there and the marks of a recent encampment were plainly visible, but the troops were gone. My heart resumed its place. It occurred to me at once that Harris had been as much afraid of me as I had been of him. This was a view of the question I had never taken before; but it was one I never forgot afterwards. From that event to the close of the war, I never experienced trepidation upon confronting an enemy. . . .

Ulysses S. Grant was promoted to brigadier general. When Confederate forces invaded neutral Kentucky, Grant moved swiftly, proclaiming that he was acting in Kentucky’s defense, taking the city of Paducah. Grant once said, “The only way to whip an army is to go straight out and fight it.” That was his modus operandi, inhibited only when he had cautious or conspiring superiors working against him. There was something else too. Grant confessed in his memoirs that “One of my superstitions had always been when I started to go any where, or to do anything, not to turn back, or stop until the thing intended was accomplished.”20 That superstition— or tenacity—was put at the service of the Union with devastating effect.

On 5 November 1861, Ulysses S. Grant moved with boats and troops to Belmont, Missouri, on the Mississippi River, where in a short, sharp battle, he scattered a Confederate detachment—only to find the Confederates reforming to cut him off from his transports. The boys in blue—whose victory celebrations had been premature—had a sweaty time of it, but Grant reminded them: “We cut our way in and we can cut our way out,” and so they did. If Grant was still learning generalship, he displayed all the right moral virtues: mounted on his horse he was the last man up the gang plank to safety. He was also lucky. “When I first went on deck I entered the captain’s room. . . and threw myself on a sofa. I did not keep that position a moment, but rose to go out on deck. . . . I had scarcely left when a musket ball entered the room, struck the head of the sofa”—right where his head had been.

States like Kentucky, Missouri, and Union-occupied Tennessee confronted the army with what to do with runaway slaves and what position to take with slave-owning families (some of which were pro-Confederate and others pro-Union). Ulysses S. Grant confessed, “My inclination is to whip the rebellion into submission, preserving all constitutional rights [including the right to slavery]. If it cannot be whipped in any other way than through a war against slavery, let it come to that legitimately.” John C. Frémont had tried to abolish slavery in Missouri and had been rebuked, indeed relieved of his command, by the president.

In the West, the eventually settled policy was to leave slave-owning Union families alone, but to enforce penalties on slave-owning Confederate families. For instance, in southeast Missouri, where Ulysses S. Grant said, “there is not a sufficiency of Union sentiment left in this portion of the state to save Sodom,” pro-Southern households could be subject to additional taxes (in order, it was said, to support pro-Union refugees). In Memphis, a very pro-Confederate city, Grant appropriated the grand house of one Confederate sympathizer for his own use and that of his family and sent the owner to a Federal prison. As for fugitive slaves, the army was entitled to employ them rather than return them to their masters.

“Unconditional Surrender” Grant

Before Belmont, Ulysses S. Grant had said, “What I want is to advance.” That desire was constant. But equally constant were the impediments put in his way, chiefly by Henry “Old Brains” Halleck who had replaced Frémont as regional commander. General George McClellan memorably said of Halleck: “Of all the men whom I have encountered in high position, Halleck was the most hopelessly stupid. It was more difficult to get an idea through his head than can be conceived by anyone who never made the attempt. I do not think he ever had a correct military idea from beginning to end.” Halleck was a jealous, short-sighted, bureaucrat of a general, and as long as he was under Halleck’s command Grant suffered (and had to endure constant rumors about his drinking) until President Lincoln promoted Grant above his restrainers.

Ulysses S. Grant’s next desired target was Fort Henry on the Tennessee River, followed by Fort Donelson on the Cumberland. Halleck restrained him at first, but Flag Officer Andrew Foote of the United States Navy came to Grant’s aid, saying that with Grant operating by land and Foote by river, they could capture the forts. Halleck’s permission in hand, Fort Henry was quickly subdued. Fort Donelson was more challenging, because it had been reinforced. But Donelson not only fell, it fell in such a way as to gain Grant national fame.

Left holding the fort after generals Gideon Pillow and John Floyd had abandoned it, was General Ulysses S. Grant’s old friend and benefactor General Simon Bolivar Buckner. Buckner sent a message to Grant to negotiate a surrender. Grant wrote back, saying, “No terms except an unconditional and immediate surrender can be accepted. I propose to move immediately upon your works.”

Buckner, clearly taken aback, confessed that he had no choice but “to accept the ungenerous and unchivalrous terms you propose.” 26 Ungenerous and unchivalrous, they might have been, but for folks up North they made U. S. Grant “Unconditional Surrender” Grant.

Ulysses S. Grant’s success (he had even, without orders, helped force the surrender of Nashville) put him further afoul of Halleck who tried to get him dismissed. General George B.McClellan, for a short while yet the commander of all Union forces, told Halleck that if he had to arrest Grant for the good of the service than so be it. But when Lincoln strippedMcClellan of his title of general in chief and Grant himself threatened to resign over Halleck’s incessant complaints, “Old Brains” Halleck had enough political grey matter to realize that he needed to give Grant some rein. Grant’s men went back on the move, gathering at Pittsburgh Landing on the Tennessee River.

Ulysses S. Grant was an aggressive commander and strong on strategy, but like a chess player so consumed with his plan to force a checkmate in four moves, he neglected to think about what his opponent would do. After Grant’s initial thrust at Belmont, his men had been surrounded. At Fort Donelson, the Confederates almost forced a breakout. Now, at Pittsburgh Landing, three miles from Shiloh Church, Grant plotted his attack on Corinth. He did not suspect that the Confederates might attack him.

The Battle of Shiloh began badly, the Federals driven back in scenes of carnage more horrendous than ever before witnessed on this continent. At the end of the first day’s fighting, Ulysses S. Grant sat beneath a tree, rain saddening his uniform and dripping from his hat (he’d decided that he’d rather rest here than among the wounded). He smoked a cigar and nursed a badly bruised ankle, injured when his horse had slipped and fallen. Sherman came up to him, wondering if they should retreat, and said, “Well, Grant, we’ve had the devil’s own day, haven’t we?” Grant replied: “Yes. Lick ’em tomorrow, though.” Grant’s determination—as well as a massive infusion of Federal reinforcements and the tentative generalship of Confederate commander P. G. T. Beauregard—ensured the Federals’ success.

Though Grant could claim a victory at Shiloh, in popular opinion it was an almost unbearable one. More then 13,000 boys in blue had been killed, wounded, or gone missing in a single battle. The shock was so profound, and some of the newspaper reports so misleading and slanted against Grant, that the hero of Fort Donelson was made to look an insensible brute, and his reputed falls from sobriety became a matter of public debate.

Ulysses S. Grant’s enemies, including Halleck, sprang. Halleck reorganized the armies of the Department of the Mississippi and left Grant without a command, kicking him into an office as Halleck’s purported deputy, without any substantial duties. Grant, however, had a more important friend than Halleck, namely the president of the United States. When President Lincoln was told he must sack General Grant in order to appease public outrage over the losses at Shiloh, Lincoln was adamant, “I can’t spare this man. He fights.” Lincoln’s solution was to promote Halleck to general in chief. Grant became commander of the Army of the Tennessee, and immediately set his sites on capturing Vicksburg.

Vicksburg was the Gibraltar of the Confederacy. Take that, and the Mississippi River, from New Orleans to Chicago, would be in Federal hands, a major tributary of Confederate supplies and men would be shut off, and

Texas, Louisiana, and Arkansas, would be severed from the rest of the Confederate States of America by a curtain of Union blue. It took two campaigns to seize Vicksburg. But while the first petered out in the dank winter of 1862–1863, the second brought Grant not only plaudits, but, following on Lee’s defeat at Gettysburg seemed to augur the end of the Confederacy. Grant certainly thought so. In his memoirs, he wrote, “The fate of the Confederacy was sealed when Vicksburg fell” on 4 July 1863.

Ulysses S. Grant’s qualities as a commander, no matter what the rumors against him, were now unmistakable to all but the most benighted. In October 1863, he was promoted to command the Military Division of the Mississippi, a stretch of territory extending from the Mississippi River to the Appalachian Mountains. In his new role he broke the Confederate siege of Chattanooga on 25 November 1863, and then sent Sherman to break Longstreet’s siege of Knoxville, which Longstreet abandoned on 4 December 1863. Grant—still an unassuming man of quiet, disinterested devotion to duty—reached a pinnacle of military recognition when he was promoted to Lieutenant General on 2 March 1864. No man since George Washington had held that rank. The promotion was great, but also meant coming to Washington and the sort of political and diplomatic flummery that Grant disdained.

The Road to Appomattox

Less than a fortnight after his appointment, Ulysses S. Grant was back in the field, traveling with George Meade, commander of the Army of the Potomac. The final great pincer movement of the war—a war that would last another year—now began, with Sherman handling one end, Grant the other, and Phil Sheridan driving a dagger down the middle. Sherman’s blue-coats torched their way through Georgia and the Carolinas. Phil Sheridan burned out the breadbasket of the Confederacy in the Shenandoah Valley. Federal troops were also active in southeastern Virginia and along the Gulf Coast. Everywhere the Confederacy was under assault. But the focal point was with Grant and Meade and the great slugging campaign against Lee. It was yet another on to Richmond campaign, but this time directed by a man who never turned back once he set himself a goal, and whose grim resolution would not be swayed by masses of casualties. Many in the North called him a “butcher,” but Lincoln stuck by his butcher; he trusted he would serve up victory.

The campaign was one of the Federals swinging left hooks at the Confederates, then pivoting left toward Richmond, trying to find an opening to land a knockout punch on the Southern capital. Lee, however, proved a masterful counterpuncher, deflecting Union blows and so punishing the Federal forces that a lesser man (or a man with fewer moral and material resources) than Grant might have broken down in defeat.

As commander of all Union forces, Ulysses S. Grant had half a million men under his command, and traveled with an Army of the Potomac that was itself 120,000 men strong (more than twice the strength of Lee). There was no swift Union victory to be found in the Battle of the Wilderness on 5 and 6 May 1864, only 18,000 Federal casualties; or at Spotsylvania Court House, from 8 May to 21 May 1864, only another 18,000 Federal losses; or at North Anna River, from 23 May to 26 May 1864 or at Cold Harbor from 31 May to 3 June 1864, though nearly another 13,000 more dead, wounded, and missing were added in combined totals from those two battles. In short, in one month, Grant and Meade had lost nearly 50,000men to Lee’s army that numbered barely 60,000. It was in light of this that Grant said at Spotsylvania Court House, “I propose to fight it out on this line if it takes all summer.” Some of his men were less impressed, with one officer writing of the failed Union assault on Cold Harbor that it was “not war but murder.” Grant, though undaunted in his pursuit of victory, confessed that he had erred in his frontal attack on the Confederate positions at Cold Harbor, telling his staff, after more than 7,000 men had fallen, “I regret this assault more than any I have ever ordered. I regarded it as a stern necessity, and believed that it would bring compensating results; but no advantages have been gained sufficient to justify the heavy losses suffered.” Meade wrote to his wife that “I think Grant had his eyes opened [after Cold Harbor], and is willing to admit that Virginia and Lee’s army is not Tennessee and Bragg’s army.”

Ulysses S. Grant, in the words of Major General J. F. C. Fuller, who wrote two book-length studies of him, was “one of those rare and strange men who are fortified by disaster instead of being depressed.” Perhaps so; it is certainly the case that he remained immovable from his objective. He showed little emotion to his subordinates, remained apparently indifferent to danger, and continued issuing orders that showed a clear and unruffled mind. He refused to give Lee the almost mythic quality that Lee’s own men and many Federal commanders did. Lee was a commander of quality, Grant would acknowledge that, but he was not invincible. Grant said, “I never ranked Lee as high as some others in the army. . . . I never had as much anxiety in my front as when Joe Johnston was in front.”33 Given Lee’s and Johnston’s respective records, this comparison rather beggars belief, and one can’t help but wonder whether Grant was in some ways defensive about the status given to Lee both during and after the war.

Still, it was Ulysses S. Grant’s refusal to acknowledge the possibility of defeat that kept him going. The thing—victory—simply must be done, and he had the resources to ensure that ultimately it would be done. Lee remained in front of him, so Grant would continue to attack him. He did so now by investing Petersburg.

The siege of Petersburg lasted ten months, but the outcome was inevitable. Lee was finally forced to abandon Petersburg, and with it Richmond, in a desperate attempt to join forces with Joseph E. Johnston in North Carolina. Grant made this reunion—a quixotic hope in any event—impossible. The drama of the war climaxed at Appomattox Court House, where Grant, in his mud-spattered uniform accepted the surrender of the immaculately dressed aristocrat from Virginia. As Grant said, “In my rough traveling suit, the uniform of a private with the straps of a lieutenant-general, I must have contrasted very strangely with a man so handsomely dressed, six feet high and of faultless form. But it was not a matter that I thought of until afterwards.”

Ulysses S. Grant was fully aware of the poignancy of the moment. While he had rejoiced at the knowledge that Lee was meeting with him to surrender, now, face to face with the noble Confederate general, Grant felt “sad and depressed. I felt like anything rather than rejoicing at the downfall of a foe who had fought so long and valiantly, and had suffered so much for a cause, though that cause was, I believe, one of the worst for which a people ever fought, and one for which there was the least excuse.”

Their meeting, however, was cordial. Lee, correct and polite, Grant so happy to reminiscence about the old army that he claimed he almost forgot the subject of their meeting. Lee made sure he didn’t. Grant called for a pen and paper and then wrote out his terms. In his memoirs he remembered that “When I put pen to the paper I did not know the first word that I should make use of in writing the terms. I only knew what was in my mind, and I wished to express it clearly, so that there would be no mistaking it.” There was no mistaking it, or Grant’s generosity, which Lee held so highly that he refused to hear a harsh word said against Grant thereafter. Indeed, according to one source, Lee said, “I have carefully searched the military records of both ancient and modern history, and have never found Grant’s superior as a general.” But this sounds so little like Lee in style and temper as to be dismissed as apocryphal, though it is still quoted approvingly by some of Grant’s admirers.

From Lieutenant General to Commander In Chief

If Ulysses S. Grant was an unlikely lieutenant general of the United States Army, he was an even less likely president of the United States. But so it came to pass, and not once but twice: Grant, elected in 1868, became the first president since another fighting general, Andrew Jackson, to serve two full terms as president.

Grant said, “I am a Republican because I am an American, and because I believe the first duty of an American—the paramount duty—is to save the results of the war, and save our credit.” His priorities were clear: ensure the newly won rights of black Americans, destroy the Ku Klux Klan, and, as far as it could be done while achieving his first two objectives, conciliate the South. He also intended to govern frugally.

Ulysses S. Grant is generally regarded lowly as a president, largely because his administration was rife with corruption (though he himself was honest; his downfall was his trusting nature) and because the country endured an economic depression under his watch. But scandals are the stuff of little minds, and economic cycles are not always malleable to politics. The more important truth is that Grant succeeded in upholding the legacy of the Union victory.

In foreign policy, his record was mixed. He kept the United States out of a war with Spain over Cuba (that, of course, would come later) and he achieved the Washington Treaty with Great Britain, which settled damages on the British for their role in building Confederate raiders (chiefly the CSS Alabama). Where he failed—as in his attempt to annex Santo Domingo, which its president had offered to the United States—he still was undoubtedly in the right. He saw the island as a potential refuge for black Americans and as a strategic asset for the Republic. But his congressional nemesis, the Radical Republican Charles Sumner of Massachusetts (the one whom South Carolina Congressman Preston Brooks had tried to beat some sense into before the war), scuppered the attempt.

In domestic policy, it was during Grant’s administration that Congress created the Department of Justice (largely to prosecute Klansmen), Reconstruction officially ended, all the former Confederate states were allowed to elect members to Congress, and restrictions on former Confederates holding public office were quietly dropped. Grant looked forward to the day when the black man was treated “as a citizen and a voter, as he is and must remain, and soon parties will be divided not on the color line [blacks voting Republican, and white southerners voting Democrat], but on principle.”

When Ulysses S. Grant left the White House he took a celebrated tour of the world. That might have been the pleasurable part of retirement. Far less so was his being swindled out of all his money by Ferdinand Ward who had formed an investment partnership with Grant’s son Ulysses Jr., and in which Grant had sunk his savings. He was diagnosed at the same time with throat cancer. Bankrupt, he sat down to write his memoirs, hoping to provide for his family. He finished the manuscript just days before he died, penning an American classic. It was Grant’s final victory.

This article is part of our larger selection of posts about the Civil War. To learn more, click here for our comprehensive guide to the Civil War.

Would you like to learn the complete history of the Civil War? Click here for our podcast series Key Battles of the Civil War

Cite This Article

"Commanding General Ulysses S. Grant: (1822-1885)" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

July 25, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/commanding-general-ulysses-s-grant-1822-1885>

More Citation Information.