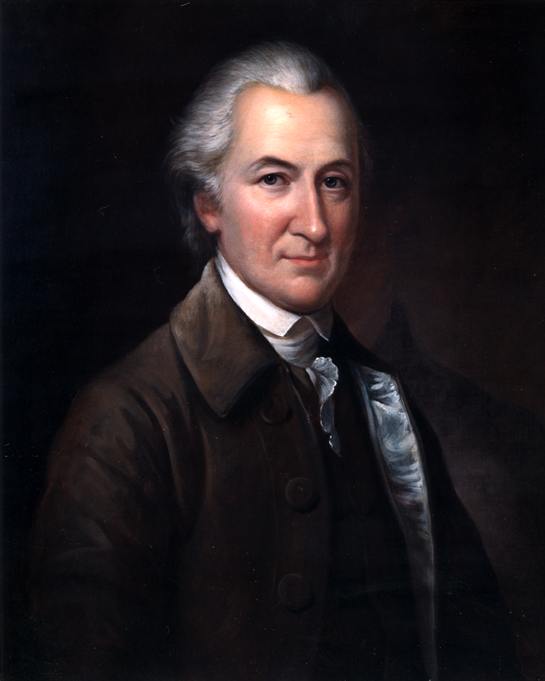

John Dickinson, the “conservative revolutionary” as one biographer called him, is one of the most unjustly neglected figures of the Founding generation. Dickinson played a role in every significant event of his time, from the Stamp Act Congress in 1765 through the Constitutional Convention in 1787. For nearly forty years, Dickinson was one of the most respected men in both Pennsylvania and Delaware, even serving for a while as governor of both states concurrently. He took part in framing both the Articles of Confederation and the United States Constitution, both of which are stamped with his conservative ideas. It is no exaggeration to say that you can’t really understand the American War of Independence without understanding John Dickinson.

He was born in 1732 at the family tobacco plantation in Talbot County, Maryland in the American Colonies, to Quakers Samuel Dickinson and Mary Cadwalader. He spent most of his youth at the new family plantation near Dover, Delaware, an estate that covered six square miles. Dickinson was privately educated, and then studied law with a leading attorney in the Philadelphia bar. At 21, he traveled to London to complete his legal training, returned four years later, and established himself as one of the top lawyers in the American colonies. The people of Delaware recognized his talents, and in 1760 he was elected as speaker of the state legislature.

In 1762, the people of Philadelphia sent him to the Pennsylvania legislature where he became a fierce opponent of Benjamin Franklin and his attempts to place Pennsylvania under crown control. He believed the Penn family was corrupt and called the Pennsylvania constitution imperfect, but he did not believe that a new charter written by the king would be any better. His stand cost him his seat in 1764, but it showed Dickinson’s willingness to oppose the popular will and the passion of the moment.

“Penman of the Revolution”

John Dickinson continued his political career as a pamphleteer, and in the process, became the “Penman of the Revolution,” and the most recognized spokesman for colonial grievances against the crown. In 1765, he published The Late Regulations Respecting the British Colonies . . . Considered, a tract that took exception to the Stamp Act. Dickinson believed that the colonists needed to secure the help of British merchants in order to gain the repeal of the law, and he therefore outlined how the Stamp Act would be detrimental to their potential profits. His exposition of the subject led Pennsylvania to send him as a delegate to the Stamp Act Congress, held in New York in 1765.

John Dickinson immediately emerged as a conservative leader, jealous of colonial rights but opposed to violent retribution. He drafted the Stamp Act Resolutions, a document that emphasized the “noble principles of English liberty” and the proper role of the colonists in taxation, where he unequivocally states “that all internal Taxes be levied upon the People with their consent . . . [and] That the People of this Province have . . . this exclusive Right of levying Taxes upon themselves.” His work and principles became the basis of colonial resistance to unconstitutional Parliamentary acts. Even Whig members of the British Parliament relied on Dickinson’s language to challenge colonial taxation. His genius was recognized on both sides of the Atlantic.

Two years later, Dickinson penned his masterpiece. In 1767, he began publishing a series of “letters” anonymously in the Pennsylvania Chronicle known as the Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania to the Inhabitants of the British Colonies. As in the case of the Stamp Act Resolutions, Dickinson challenged British authority over taxation in the colonies. He stated that his intention was to “convince the people of these colonies, that they are at this moment exposed to the most imminent dangers; and to persuade them immediately, vigorously, and unanimously, to exert themselves in the most firm, but peaceful manner for obtaining relief.”

He maintained that those engaged in the “cause of liberty. . . should breathe a sedate, yet fervent spirit, animating them to actions of prudence, justice, modesty, bravery, humanity, and magnanimity.” This might seem out of line with a call for “firm” resistance, but Dickinson’s conservative instincts always inclined him to preserve order and peace— while insisting on the rights of the colonists as Englishmen. Like Patrick Henry, he was at the vanguard of public opinion in 1767, but unlike Henry, he wished to extend the “olive branch” as long as possible. His Letters became the toast of the colonies. The city of Boston thanked him in a public meeting, and Princeton granted him an honorary doctorate.

He urged his fellow Pennsylvanians not to import British goods—a reversal from his position on the Stamp Act. The people of Pennsylvania returned him to the legislature in 1770, and from there Dickinson helped propel the events that led to the War for Independence. In 1771, he authored a Petition to the King in which he implored the crown to intercede on behalf of his majesty’s colonial subjects. At the same time, he denounced some of the more violent actions undertaken in New England, a move that reduced his popularity in that section of the colonies. Dickinson showed a consistent attachment to conservative resistance. Boston approached other colonies for aid in 1774 after again sparking violence, but Dickinson believed this imprudent and instead offered only “friendly expressions of sympathy.” New England, he surmised, had destroyed any chance of conciliation, and he wanted to distance his native colony from such a policy.

He was elected chairman of the Pennsylvania Committee of Correspondence and in 1774 served for a brief time in the First Continental Congress where he wrote the Declaration and Resolves of the First Continental Congress. These resolves carefully insisted that the colonists shared a common heritage with the people of England and as such retained all the rights and liberties of free Englishmen, including the right to “life, liberty, and property” and the right to participate in legislative councils. He defined the conflict as a contest over the rights of Englishmen and not a test of ideologies or philosophies. Most important,John Dickinson wanted to restrain the potentially radical democratic sentiment emanating from some members of New England. The colonies were not pure democracies, and Dickinson hoped to keep it that way, even if a revolution were to take place, which by 1775 he considered inevitable.

He was returned to the Second Continental Congress in 1775, where he wrote the Declaration of the Causes of Taking up Arms, a petition that defended the right of colonists to resist the “tyranny” of the “aggressors” through force. “In our own native land,” he wrote, “in defense of the freedom that is our birth-right, and which we ever enjoyed till the late violations of it—for the protection of our property, acquired solely by the honest industry of our fore-fathers and ourselves, against violence actually offered, we have taken up arms.” But Dickinson also said the colonists would lay down their arms, if the British no longer violated the colonists’ rights. “We shall lay them down when hostilities actually cease on the part of the aggressors, and all danger of their being renewed shall be removed, but not before.” He followed this up with an “olive branch” petition to the king in July 1775. This document implored the king to intercede on behalf of the colonies and end the possibility of a “civil war.” When the king and Parliament declared the colonies in a state of rebellion, Dickinson prepared for the war he hoped would not arrive but had helped bring about.

John Dickinson had been elected colonel of the first battalion of militia raised in Philadelphia in 1775 and served as the chairman of the committee of public safety the year prior. Even while offering the “olive branch,” Dickinson was actively preparing his colony for war. Congress began debate on a declaration of independence in June 1776, and Dickinson made clear his objection to such action. He still hoped for conciliation.

When the document was finally presented to the Congress, he cast his vote against it—the vote was by states and not delegates—and he made one of the more brilliant speeches of his career. He did not oppose independence in principal, but he did not believe the colonies were ready to fight a war with England. They had not obtained any foreign alliances and had not adopted a plan for a stronger “union.” He later insisted that it was the timing and not the idea of independence that led him to vote “no.”John Dickinson retired from the Congress after his vote and took up arms against the British as a brigadier general in the Pennsylvania militia. But, before leaving in July 1776, Dickinson drafted a plan of union entitled “The Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union,” the general framework of which became the first governing document of the union of the States.

The British considered him a principal actor in the march to American independence and in December 1776 burned his Philadelphia home, Fairhill, in retaliation. He was forced to retreat to Delaware where he helped plan the defenses of his home region during the war. He served as a private soldier at the Battle of Brandywine in 1777, and in 1779 Delaware sent him back to the Continental Congress. His term in the Congress lasted two years, and in 1781, Delaware elected him president of the state. Pennsylvania likewise chose him to serve in the same capacity in 1782, so for two months,John Dickinson served as the executive of two states. He resigned from his position in Delaware but maintained his office in Pennsylvania until 1785.

The Convention

John Dickinson retired to his Dover plantation in 1785. He was chosen the next year to act as the chairman of the Annapolis Convention, the meeting that led to the call for a new constitution. Delaware then chose him to lead the state delegation at the Philadelphia Convention in 1787, and it would be his brand of federalism that led to a new constitution. It could be argued that Dickinson was more important to the final document than James Madison. His contemporaries expected much from him. Illness prevented him from participating as fully as they hoped, but when present, he was a constant check on the slippery slope of reason and theory. He was directed by the powerful hand of British and American tradition, the only guide he had followed throughout his career.

He supported a new constitution for specific purposes, namely common defense, commerce, foreign affairs, and revenue. This position had been unchanged since he first opposed the Declaration of Independence in 1776. He was reluctant, however, to concede too much to a new central government. The states, in his estimation, had to remain sovereign, and he almost immediately suggested that each state have equal representation in the new government. This may be discounted as a ploy to protect his small state, but John Dickinson called both Pennsylvania and Delaware home, and his other remarks suggest that he wanted to preserve the sovereignty of the separate states in order to ensure local customs, traditions, and order. He argued that liberty was grown and preserved by the local communities, not the central government, and these local communities would be the most vigorous agents for its defense. The history of both Rome and England had proven this, and now, he argued, the United States should follow the same path.

As during the Revolution, he feared the excesses of democracy, and was especially worried about the masses confiscating the property of others through the vote. At the same time, he worried about the potential of an artificial aristocracy able to secure economic privilege if too much power was placed in the hands of the central authority. There had to be a median, and to Dickinson the perfect model was the English constitution adapted to American circumstances and conditions. He compared the Senate to the House of Lords and the House of Representatives to the House of Commons. He argued that the executive branch and Supreme Court should be restrained by both the Congress—most importantly the Senate—and the states, and he warned against constitutional “innovations” that had no historical precedent.

Dickinson signed the Constitution because he believed it provided the best form of republican liberty in the history of the world and later defended it in a series of letters published under the name “Fabius” in 1788. These nine essays rival the more famous Federalist Papers in substance and argument. In true form, Dickinson’s letters were the median between the Anti- Federalist attacks on the Constitution and Hamilton’s infatuation with a powerful central government.

John Dickinson believed that an affirmation of states’ rights was inherent in the Constitution. He stated in essay nine, “America is, and will be, divided into several sovereign states, each possessing every power proper for governing within its own limits for its own purposes, and also for acting as a member of the union.”

Translation: the states are sovereign, and the federal government has specific, delegated powers. Those not listed are reserved to the states (as per the tenth amendment to the Constitution). A central government could never protect the liberty of the people without proper safeguards, among them being the sovereignty of the states.

Retirement

John Dickinson never again held public office after the Constitutional Convention. He spent his final years mostly in Delaware living the life of a planter. Though a slave owner, he proposed the gradual abolition of slavery in Delaware and thought state laws in relation to the institution should be reviewed. He broke with the Federalist Party when he determined they had violated the principles of the Constitution and the spirit of the union and became an independent supporter of the Jefferson administration until his death in 1808. Contemporaries described him as a man of honor, integrity, and character.

His firm support of liberty led him to reluctantly accept a break with Britain in 1776, and his belief in the sovereignty of the states and the aristocratic checks of the Senate and the Electoral College fostered his support of the Constitution in 1787. John Dickinson led a life of moderation, and was a man who pursued every means to achieve peace and liberty throughout his public career. His final words were, fittingly, “I wish happiness to all mankind, and the blessings of peace to all the nations of the earth, and these are the constant subjects of my prayers.” This pious, conservative, liberty-loving, states’ rights advocate seems out of touch with modern society. This might be why he is routinely ignored by left-leaning history professors.

Cite This Article

"John Dickinson: Penman of the Revolution" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

July 25, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/founding-fathers-john-dickinson-penman-revolution>

More Citation Information.