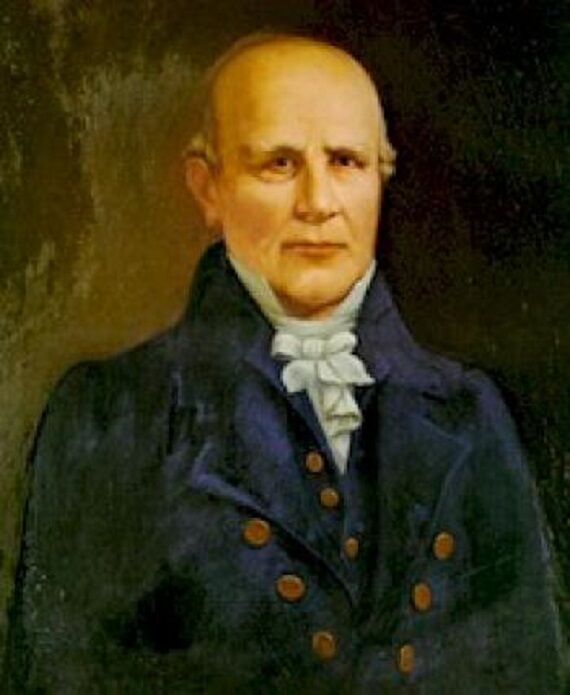

Nathaniel Macon was quite possibly the most important man in the history of the Tar Heel State, North Carolina. Jefferson called him the “last of the Romans”—meaning a republican who favored limited government, frugality, and selfless service—and Macon’s friend and political ally, John Randolph of Roanoke, described him as the wisest man he ever knew. Most Americans have probably never heard of Macon. Modern history texts rarely mention him, if at all.

Among the Founding Fathers, he was everything that politically correct interpretations of American history try to avoid. Nathaniel Macon championed states’ rights, supported secession, denounced the Constitution, presided over a large tobacco plantation, served with distinction in the Revolution in defense of his state and region, and opposed every measure that tended to increase centralization and federal power. He lived a simple life, and though a genuine Southern aristocrat, was never pretentious. Macon was the personification of the Old South, and an American hero.

The first Macon, a French Huguenot named Gideon Macon, arrived in Virginia of the American Colonies before 1680 and became a prominent tobacco planter in the tidewater region of Virginia. His grandson, Gideon Macon, moved to North Carolina in the 1730s, established a tobacco plantation, and built the family home, Macon Manor. The Macon family was well connected in both Virginia and North Carolina. For example, George Washington’s wife, Martha Dandridge Custis Washington, was descended from this line. Gideon Macon and his wife, Priscilla Jones, had six children. The last, Nathaniel Macon was born in 1758, and was only five when his father died. Nathaniel was bequeathed around five hundred acres, three slaves, and all of his father’s blacksmith tools. From 1766 to 1773, Macon was educated by Charles Pettigrew, grandfather of the famous Confederate general by the same name, and later attended the College of New Jersey, otherwise known as Princeton University.

He left the college when the War for American Independence began in 1775 and enlisted with the New Jersey militia. He served one year, returned to North Carolina and began the study of law. He again enlisted for military duty in 1780 when his state was threatened by the British invasion of the South. Nathaniel Macon refused a commission, and also refused the bounty offered for enlistment. He fought at the Battle of Camden. When chosen to serve in the state Senate in 1781, he initially refused, but later accepted as a favor to General Nathanael Greene. Macon regarded his military service as service to his state—as did most Americans serving in the War for Independence—not to any union represented by the Continental Congress.

He served in the state legislature for the remainder of the 1780s. While there, he met and befriended Willie Jones, the dominant Anti-Federalist in North Carolina. The state elected Macon to serve in the Continental Congress in 1786, but he declined, and when several states called for a convention to discuss changes to the Articles of Confederation, Macon opposed North Carolina’s participation. He did not attend the North Carolina ratification convention, but, along with his brother, John Macon, urged the defeat of the Constitution. North Carolina would not ratify the document until 1789, and only after the Bill of Rights—especially the Ninth and Tenth Amendments—were guaranteed.

He served in the United States House of Representatives from 1791 to 1813 and in the United States Senate from 1813 to 1828. He was Speaker of the House for six years and president pro tempore of the Senate for one. His thirty-seven years of service occurred during the formative years of the republic, and he became a leading “negative” on federal action. Few other members cast as many “no” votes as Macon. One biographer called him a “negative radical,” but this derogatory term does not do Macon justice. He voted “no” so often because he believed the federal government continually abused its authority and unconstitutionally enlarged its scope and influence. He took friend and foe alike to task for their support of unconstitutional measures.

The Quid

Macon was identified as one of a group of thirteen “Quids” during his time in Congress. John Randolph of Roanoke bestowed the title on the group because their consistent attachment to limited government made them the other “thing” (in Latin, a quid is a “thing”) in relation to the Federalists and the Republicans. Macon was the recognized leader of the North Carolina delegation to the House of Representatives. He immediately characterized Alexander Hamilton as the “supreme evil-doer” and joined the opposition to his economic programs. Southerners believed that New England and New York were exercising too much influence on the general direction of the United States, especially in advancing Northern commercial interests against Southern agrarian interests. Macon shared that view.

Macon suggested a series of excise taxes in 1794 that would have extended the burden of the “whiskey tax” onto other beverages like beer, porter, and cider. His intent was to spread the pain, given that the whiskey tax fell disproportionately on Western and Southern farmers. Macon and other Southern leaders felt that the whiskey tax was a political tax, imposed by Northern Federalists on Southern Republicans. In 1788, when Federalists attempted to limit free speech through the Sedition Act, Macon at once challenged the bill. He declared the provisions of the sedition law violated the spirit of 1776, and claimed that “the people suspect something is not right when free discussion is feared by government. They know that truth is not afraid of investigation.” It was true, he conceded, that states had exercised the same power of the Sedition Act, but that was within their constitutional authority. He reasoned “let the States continue to punish, when necessary, licentiousness of the press”; what he denied was the federal usurpation of this right. Moreover, Macon argued the bill violated the First Amendment to the Constitution. “How can so plain language be misunderstood or interpreted into consistency with the bill before us?”

Nathaniel Macon consistently challenged federal designs to weaken the states and institute legislation that conflicted with republican principles of government, and he supported the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions of 1798, where Madison and Jefferson put forward the argument that the states could nullify federal legislation. Macon went further, stating that if the states wished to end the federal government, they could do so because “the Government depends upon the State Legislatures for existence. They have only to refuse to elect Senators to Congress and all is gone.” This would have worked in 1798, but after the Seventeenth Amendment (1913) and the direct election of senators, this was no longer the case. Macon would certainly have opposed that glaring reduction of state power. But Macon did not focus singly on matters of state and federal power.

He was a firm advocate of fiscal responsibility. For example, he voted against spending $7,000 (around $120,000 2007 dollars) on a monument to George Washington, not because he did not think Washington deserved the honor, but because the sum was too large and not an appropriate expenditure for the Federal government in any case. When Federalists asked for enormous sums of money to wage a war against France, Macon responded by saying, “Some people think borrowing five or six millions a trifling thing. We may leave it for our children to pay. This is unjust. If we contract a debt we ought to pay it, and not leave it to your children. What should we think of a father who would run in debt and leave it for his children to pay?” He also asked, “Ought we not to save all the expenses which are not absolutely necessary?”

Macon’s independence was shown in his willingness to oppose those in his own party when they deviated from republican principles. Jefferson realized this in his second term. This is when Macon became identified as a “Quid.” For a time, Macon attacked and ridiculed President Jefferson at every turn for what Macon regarded as Jefferson’s inconsistent adherence to republican principles and the Constitution. Macon was not a “party man.” He voted his beliefs. In fact, Macon was the model of the disinterested statesman. He did not seek election during the Revolution. When his state chose him to serve in the United States Senate, it was at the state legislature’s insistence, not his. He was elected Speaker of the House three times, though he never actively campaigned for the position. When he was defeated for a fourth term in 1807, he never said a word about it. He turned down several offers of more “prestigious” positions in the federal government, from cabinet appointments to Vice President. Macon shunned the “glamour” of political office, and was a selfless public servant for his state.

The Republican of Buck Spring

Buck Spring was a remote, sprawling tobacco plantation in Warrenton, North Carolina, that at one time covered two thousand acres. This was Macon’s home and in the republican tradition of departing public life gracefully, he retired there in 1828. Macon lived twelve miles from the nearest post office and only received mail once every two weeks. His wife had died when he was thirty-two, and Macon never remarried. He lived alone but peacefully among his seventy slaves. He brought his entire group of slaves with him to church services once a month and had a separate service every Sunday at his home. His slaves were required to participate, and elder slaves would often lead a prayer. He was a genuine Southern aristocrat but a man of simple tastes. He ate what the plantation produced and preferred corn whiskey. He was fond of thoroughbreds and kept at least ten fine horses, and he enjoyed such Southern activities as fox chasing. Unless visitors called, Macon rarely had contact with the outside world. Buck Spring was his first country, North Carolina his second.

Nathaniel Macon did, however, stay abreast of the current political debates even in retirement. When South Carolina nullified the federal tariff in 1832, several leading Southerners pressed Macon for an opinion. He had supported nullification in 1798, but his attitude had changed. He believed nullification alone would not be enough to check Northern usurpation of power and argued secession was the only remedy. “I have never believed a State could nullify and stay in the Union, but have always believed a State might secede when she pleased, provided she would pay her proportion of the public debt, and this right I have considered the best guard to public liberty and to public justice that could be desired.” He sent a strong letter to President Andrew Jackson critical of his threat to use military force to collect the tariff. Macon contended the federal government could not legally use force against a state in order to “maintain the Union.”

He also opposed the re-charter of the Second Bank of the United States. Macon fought against the Bank for forty years. He voted against the Bank while Speaker of the House and once said that “Banks are the nobility of the country, they have exclusive privileges; and like all nobility, must be supported by the people and they are the worst kind, because they oppress secretly.” When President Jackson vetoed a bill supporting re-charter in 1832, Macon applauded the move. Like other republicans of his day, Macon considered the bank to be a symbol of Northern corruption.

One of Macon’s final forays into public life occurred in 1835 as a member of the state constitutional convention called to revise the state constitution of 1776. He pressed for religious liberty, suffrage based on “maturity” rather than property, public funding for education, and open government that was accountable to the people.

The 1776 constitution granted the vote to free blacks who met the existing property qualifications. Macon opposed repealing that provision but was defeated. His proposal for yearly elections was also voted down. In the end, Macon opposed ratification of the new constitution, which passed anyway. Though a formidable political opponent, Macon extended Southern hospitality, even for his enemies. “While life is spared, if any of you should pass through the country in which I live, I should be glad to see you.” He believed the convention was his final act, but he took an active role in the 1836 presidential contest as an elector from North Carolina. He supported the New Yorker Martin Van Buren because his election meant the triumph of “Southern Republicans” and “principle.” He said after the election that it was the “best evidence in the world of the indomitable spirit of democracy.”

Nathaniel Macon died one year later, suddenly, at Buck Spring, at the age of seventy- nine. He gave instructions to bury him next to his wife and son and to cover the grave in piles of flint rock so the plot would remain undisturbed, and it remains so today. Fifteen hundred people attended his funeral, and, as per his will, he provided all with “dinner and grog.” One participant recalled that “No-one, white or black, went away hungry.” Macon, Georgia, and Randolph-Macon College were named in his honor, as well as counties in Alabama, Tennessee, Illinois, and North Carolina. He called North Carolina his “beloved mother,” and his son-in-law presided over North Carolina’s secession convention in 1861. Macon was a republican who believed in the “principles of ’76.” No other man better exemplifies the devotion to states’ rights that was so important a part of the Founding generation.

Cite This Article

"Nathaniel Macon: King of the Tar Heels" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

April 25, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/founding-fathers-nathaniel-macon>

More Citation Information.