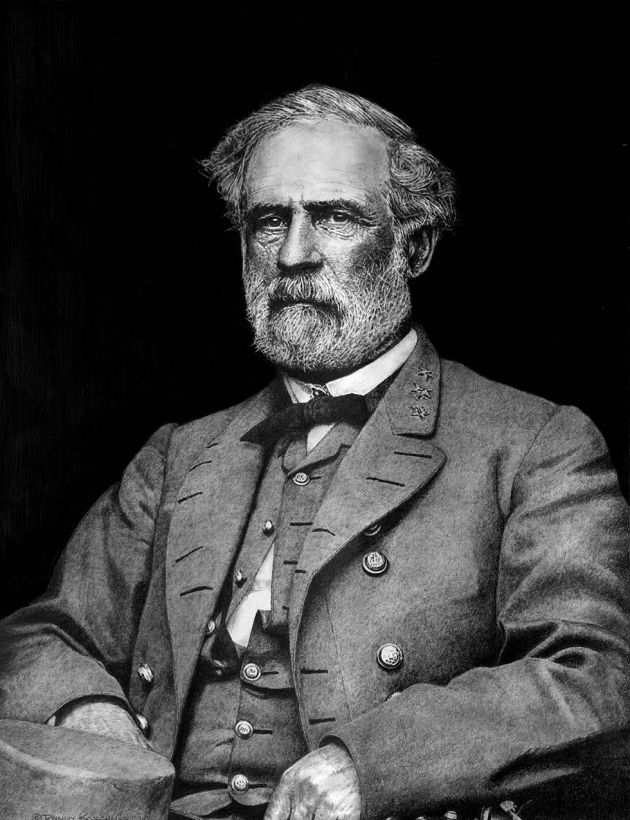

General Lee left a mark on American history as one of the greatest generals during the American Civil War. Learn more about his role in the war based on his battle records.

GENERAL LEE CIVIL WAR RECORD

Civil War record of General Lee was considerably less impressive than the Myth of the Lost Cause portrays it. After declining command of the Union army because he would not lift his sword against his beloved Commonwealth of Virginia (as distinguished from the Confederacy), Lee did an excellent job organizing the Virginia militia and defending that state in the early months of the war. As its militia became part of the Confederacy’s army, Lee became President Jefferson Davis’s military advisor.

Disappointed that he was not on the field for the Confederate victory at First Bull Run (Manassas), Lee continued to lobby for a field command. His wish was granted when he was sent to northwestern Virginia in late 1861, but there he demonstrated some of the weaknesses that would plague him throughout the war. At Cheat Mountain, he issued long, complicated orders and failed to exercise hands-on control. While in that small theater, he failed to deal with squabbling subordinates whose disputes were undermining Confederate efforts to regain control of northwestern Virginia, and he returned to Richmond a failure.

Davis then gave General Lee a chance for redemption by assigning him to command the South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida coasts. First, Davis had to write letters to affected governors ensuring them that Lee was indeed a highly competent general (contrary to what they may have heard about his western Virginia experience). Lee did an excellent job building defensive coastal fortifications and withdrawing most of the rebel defenses to waters beyond the reach of Union gunboats.

Apparently because Davis was becoming disenchanted with independent, uncooperative, and personally despised generals such as Joseph Johnston and P. G. T. Beauregard, he recalled Lee to Richmond as his primary military advisor once again. There Lee helped Davis to pressure Johnston into more aggressive defensive actions, especially after George B. McClellan started slowly moving up the Virginia peninsula from the Norfolk area toward Richmond.

After two months of dalliance, McClellan finally reached the vicinity of Richmond and split his army on both sides of the Chickahominy River. On May 31, 1862, with prodding, Johnston attacked an isolated portion of Little Mac’s army on the south side of the river. In what became the two-day Battle of Seven Pines (Fair Oaks), Longstreet bungled his attack, and reinforcements from north of the river were able to avert a Union disaster.

The most important result of the battle was that Johnston was badly wounded and on June 1, 1862, General Lee succeeded to command of the major Confederate army in the east, which he promptly dubbed the Army of Northern Virginia. His record as its commander requires deep examination before judgment can be rendered about the quality of his Civil War performance.

General Lee enhanced his early-war reputation as the “King of Spades” by ordering his army to dig fortifications south of the Chickahominy between Richmond and McClellan’s Army of the Potomac. Contrary to many people’s expectation that he would be a cautious general, he was preparing the first of many offensives against his foes. His strategic and tactical aggressiveness would soon be apparent to all.

The Seven Days’ Battle, ending McClellan’s disastrous Peninsula Campaign, began in late June and was Lee’s first as army commander. Correctly predicting that McClellan would not have the moral courage to attack Lee’s lines and Richmond while General Lee moved his army to the north side of the Chickahominy, Lee took two-thirds of his army above the river and attacked Little Mac’s largest corps, which was alone there.

In a sign of things to come, General Lee had his army attack the enemy for most of one week and pushed them away from Richmond and back to the James River. Although Lee knew that he had achieved his strategic objective of saving Richmond after two days of fighting, he continued his attacks for days more, taking substantial casualties. His army suffered twenty thousand casualties (dead, wounded, missing, or captured), while McClellan’s army suffered “only” sixteen thousand. Most of Lee’s casualties were “hard” ones—killed or wounded. Only ten thousand of Little Mac’s men were killed or wounded.

That week of fighting was marked by McClellan’s constant retreats (under his usual misapprehension that he was outnumbered two to one) and Lee’s over-aggressiveness and mismanagement of his army. He generally issued a battle order for the day and then simply let things unfold without close battlefield control by him or his deliberately small staff. Virtually every daily order called for Stonewall Jackson to come in on Lee’s left flank after the rest of Lee’s army diverted the Yankees’ attention with frontal assaults. While those assaults resulted in horrendous casualties, Jackson was either a no-show or late-show on almost every occasion. General Lee took no corrective action.

The final battle of the week was Malvern Hill, where a disorganized and disastrous rebel assault against a strong, elevated Union position resulted in such slaughter that D. H. Hill, one of Lee’s generals, described it as “not war, but murder.” By then, Lee had so decimated and disorganized his army that McClellan’s subordinates recommended an immediate counterattack to destroy Lee’s army or capture Richmond. McClellan, of course, declined and retreated farther downriver.

Lee’s strategic victory made him an instant hero in the South, which was losing battles on most other fronts. He had, however, demonstrated a proclivity for complicated and ambiguous orders, lack of battlefield control, and relentless offensive action that resulted in irreplaceable casualties for the manpower-starved Confederacy.

While McClellan, pouting at Harrison’s Landing on the James River, kept requesting more reinforcements, General Lee determined that the Army of the Potomac was no threat to Richmond and decided to go on the offensive. He moved into central and northern Virginia to challenge John Pope’s new Army of Virginia. With help from McClellan, who delayed sending reinforcements to Pope and kept twenty-five thousand Union troops away from the battlefield, Lee won perhaps his greatest victory at Second Manassas. With Jackson on the defensive and Longstreet then overwhelming Pope’s left flank, Lee suffered only 9,500 casualties to the Union army’s 14,400. With Lee present, Jackson inexplicably failed to leave his position and join Longstreet’s attack.

After a minor victory at Chantilly, Lee took unilateral action, approved neither by Davis nor the Confederate Congress or cabinet, that proved devastating to rebel prospects—he crossed the Potomac and invaded the North in hopes of reaching Pennsylvania. In that Maryland (Antietam) campaign, he hoped to feed his army, gather thousands of recruits, and win a great victory that would dismay the Northern people and convince England and France to recognize the Confederacy. For about three weeks, Lee’s army lived on non-Virginia soil, but he failed to gain recruits. He was in the western part of Maryland, where proslavery sentiment was weak, and those Marylanders interested in joining his army had already done so.

More importantly, he squandered what had been a grand opportunity for European recognition. England and France had been poised to recognize the Confederacy until Lee’s invasion, but they decided to wait for the outcome of his campaign. That campaign started well for General Lee as he took advantage of McClellan’s slow response to the discovery of Lee’s “lost order” and captured more than eleven thousand Union soldiers at Harpers Ferry. Instead of declaring the campaign a success after the capture of Harpers Ferry and its garrison, however, Lee put his pitifully small and exhausted army in a trap at Sharpsburg, Maryland. In the Battle of Antietam (Sharpsburg) on September 17, he suffered severe losses and would have been destroyed by almost any general other than McClellan. Lee’s and Jackson’s counterattacks at Miller’s Cornfield in the early hours of the battle were acts of tactical suicide, not genius. Although McClellan allowed Lee’s army to escape, the Confederates had suffered a crushing strategic defeat that opened the door for Lincoln’s preliminary Emancipation Proclamation on September 22 and virtually ended all hopes of European intervention. Lee’s net casualties at Harpers Ferry had been a plus-11,500, but his army suffered 11,500 casualties in the rest of the Antietam campaign (to the attacking Union army’s 12,400).

After retreating to Virginia, General Lee was the beneficiary of foolhardy Union assaults ordered by Ambrose Burnside at Marye’s Heights at Fredericksburg in December 1862. Lee’s army, fighting from entrenched positions most of the day, inflicted almost thirteen thousand casualties on the Union attackers while incurring a few more than five thousand themselves. Although Lee was not satisfied with the defensive nature of the victory, it was sufficient to bolster Southern morale for many months.

The lesson of Fredericksburg was that a frontal assault on the enemy, if not absolutely necessary, was unwise, but Lee failed to learn it. After Stonewall Jackson’s famous flanking maneuver at Chancellorsville in early May 1863, Lee spent the next couple of days frontally assaulting Joseph Hooker’s Union lines. As a result, his army suffered almost thirteen thousand casualties while inflicting over seventeen thousand on the weakly led enemy. But Lee’s army paid too high a price, including the loss of Jackson, for the Chancellorsville victory. Its butcher bill would have been even higher had Lee been able to launch a planned final assault on another strong Union position. Lee was angry, but his subordinates were relieved, when Hooker retreated across the Rapidan River before Lee could attack.

Gettysburg proved even more disastrous to the Confederacy and the Army of Northern Virginia. By invading Pennsylvania, General Lee deprived rebel armies in other theaters of desperately needed reinforcements. Had Longstreet’s troops reinforced the badly outnumbered Bragg against George Thomas’s Tullahoma campaign, Thomas might have been prevented from crossing the Tennessee River and seizing Chattanooga and more rebel troops might have been sent to oppose Grant’s Vicksburg campaign.

On the first day of the three-day battle at Gettysburg, General Lee missed a grand opportunity to occupy the high ground, a failure that proved costly over the next forty-eight hours. Longstreet, his senior general, opposed Lee’s plan for frontal assaults on the second and third days against Union troops in strong defensive positions. That campaign cost Lee an intolerable twenty-eight thousand casualties, while the Union lost twenty-three thousand. As a result, Lee no longer had the strength to initiate strategic offensives (which had been a bad idea anyway) and, more importantly, he lacked the manpower to counterpunch effectively when attacked.

Some regard Gettysburg as a turning point of the war. Lost Cause adherents have attempted to make it the turning point and have expended considerable effort attempting to relieve Lee of responsibility for that major tactical and strategic defeat. Their position is that Longstreet lost Gettysburg and thus the war, while Lee was blameless. Although Douglas Southall Freeman recited a litany of guilty parties (Longstreet, Ewell, A. P. Hill, Jeb Stuart), most of Lee’s apologists found the only scapegoat they needed in James Longstreet. Because the Lee-Longstreet saga has become such a fundamental part of the Myth, I have devoted the next chapter to a thorough examination of the Gettysburg campaign and the allegations against Longstreet. Readers can determine for themselves whether Lee or Longstreet was primarily responsible for that disaster.

The cumulative casualties of 1862 and 1863 had taken a severe toll on Lee’s army—both in the number and the quality of the men lost. It was a toll the Confederacy, outnumbered almost four to one at the war’s outset, could not afford. With an army that was a mere shadow of the one he had inherited, Lee was finally forced to fight truly defensively in opposing Grant’s Overland Campaign of 1864. Staying generally on the defensive at the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Court House, the North Anna River, and Cold Harbor enabled Lee to post the kinds of numbers he had needed in prior years. Before Grant had reached the James River, Lee lost “only” thirty-three thousand men while inflicting fifty-five thousand casualties on the Army of the Potomac. But it was too little, too late, for Lee. He had so weakened his army with his offensive strategy and tactics in 1862 and 1863 that he could not prevent Grant from forcing him into a partial siege situation at Richmond and Petersburg in which Lee’s army was doomed. Thereafter, he continued to focus solely on his own army as the rest of the Confederacy was collapsing.

Ironically, the Overland Campaign of 1864, in which Grant, according to his critics, took too many casualties, shows what Lee could have accomplished had he stayed on the strategic and tactical defensive in 1862 and 1863. As Alan Nolan concludes, “The truth is that in 1864, General Lee himself demonstrated the alternative to his earlier offensive strategy and tactics.” Grady McWhiney reaches the same conclusion: “Though Lee was at his best on defense, he adopted a defensive strategy only after attrition had deprived him of the power to attack. His brilliant defensive campaign against Grant in 1864 made the Union pay in manpower as it had never paid before. But the Confederates adopted defensive tactics too late; Lee started the campaign with too few men, nor could he replace his losses as could Grant.”

Would you like to learn the complete history of the Civil War? Click here for our podcast series Key Battles of the Civil War

Would you like to learn the complete history of the Civil War? Click here for our podcast series Key Battles of the Civil War

Cite This Article

"A Closer Look at General Lee’s Civil War Record" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

July 27, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/general-lee>

More Citation Information.