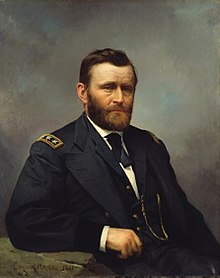

How well do you know General Grant? In this article, you’ll find out the other side of General Ulysses S. Grant’s life.

GENERAL GRANT – OTHER PARTS OF HIS LIFE

The persistent criticisms of General Grant can be summarized as follows: (1) he was a butcher, (2) all he did in the war was bludgeon Lee’s army in the Overland and Appomattox campaigns, (3) he attacked unnecessarily, (4) his armies suffered more casualties than Lee’s, (5) he attacked Lee needlessly in the Overland Campaign, (6) the election of 1864 was such a landslide for Lincoln that Grant’s aggressive series of nationwide campaigns was unnecessary, and (7) his high casualties in 1864–65 show that he was inferior to his predecessors in the Eastern Theater.

There are answers to each of these criticisms.

(1) Far from being a butcher, General Grant fought with skill, audacity, swiftness, and aggressiveness. As a result, he imposed about thirty-seven thousand more casualties (killed, missing, wounded, captured) on his opponents than his own armies incurred.

(2) Prior to coming to the East to defeat Lee, Grant had won a series of major campaigns and battles—including the Fort Henry–Fort Donelson Campaign, the brilliant Vicksburg campaign, and the Battle of Chattanooga—with swift and daring movements and a minimum of casualties.

(3) The strategic burden of winning the Civil War was on the North. The North had to defeat the South, and Grant was by far the most effective Union general in going on the offensive to win the war. On the other hand, the South needed only a deadlock or a tie, but Lee gambled by going on the offensive and thus decimated his own army at Seven Days’ (especially Mechanicsville and Malvern Hill), Chancellorsville, Gettysburg (especially on Day Two and then Pickett’s Charge on Day Three), the Wilderness, and Fort Stedman. General Grant needed a win, went for it, and got it. Lee needed a tie, went for the win, and lost.

(4) In their authoritative study of the war’s casualties, Grady McWhiney and Perry Jamieson find that Lee’s army suffered about 121,000 killed and wounded while Grant’s armies suffered about 94,000 killed and wounded. In those major battles, they concluded, Lee’s army suffered an average of about 20 percent killed and wounded in each battle, while Grant’s armies suffered about 18 percent killed and wounded. An all-encompassing study of the war’s casualties reveals that Lee’s single losing army incurred about 209,000 casualties (killed, wounded, missing, captured), while General Grant’s several winning armies incurred a total of about 154,000 casualties—about 55,000 fewer than Lee’s.

(5) Lincoln brought General Grant to the East as general in chief to pursue Confederate armies aggressively and perhaps win the war in time to ensure Lincoln’s reelection in 1864. In the several months he had to accomplish that goal, Grant drove Lee’s army into a virtual siege at Richmond and Petersburg, keeping Lee so occupied that he never considered aiding rebel forces defending Atlanta. Sherman’s capture of Atlanta in September, while Grant had Lee bottled up in Virginia, was decisive in Lincoln’s reelection.

(6) Although Lincoln beat George McClellan by a margin of 55 to 45 percent in the November 1864 election, as late as the end of August virtually everyone (including Lincoln, Republican Party leaders and newspaper editors, and Confederate observers) thought Lincoln would lose. The fall of Atlanta changed Lincoln’s prospects. Still, a switch in certain states of fewer than thirty thousand votes, out of the four million cast, would have given McClellan the electoral votes to defeat Lincoln—even after Atlanta, the Shenandoah Valley, and Mobile had been the scene of major Union victories within the ten weeks preceding the election.

(7) Grant’s Eastern predecessors—including McClellan, Burnside, Hooker, and Meade—incurred more casualties in the East (about 144,000) than Grant and had little to show for them. They lacked Grant’s perseverance. After their three years of strategic failure, Grant won the war in less than a year after launching the Overland Campaign.

General Grant was about as aggressive as Lee, but his aggression was consistent with the Union’s strategic and tactical need to take the war to the rebels, destroy their armies, and affirmatively win the war. With about fifty-five thousand fewer casualties than Lee, Grant won two theaters of the war, saved a Union army in a third, and proved to be the most successful general of the war. Yet in Gordon C. Rhea’s words, “[t]he very nature of Grant’s [offensive] assignment [especially in 1864] guaranteed severe casualties.”

In fact, an average of “only” 15 percent of General Grant’s Federal troops were killed or wounded in his battles over the course of the war—a total of slightly more than 94,000 men. In contrast, Lee had greater casualties both in percentages and real numbers: an average of 20 percent of his troops were killed or wounded in his battles—a total of more than 121,000 (far more than any other Civil War general). Lee had about 80,000 of his men killed or wounded in his first fourteen months in command (about the same number he started with). All of these casualties should be considered in the context of America’s deadliest war. At least 620,000 military men died in the Civil War, 214,938 in battle and the rest from disease and other causes. Perhaps another 130,000 civilians and soldiers (primarily Confederate) were unaccounted for.

In their thought-provoking book Attack and Die: Civil War Military Tactics and the Southern Heritage, McWhiney and Jamieson provide some astounding numbers related to Grant’s major battles and campaigns. First, they have determined that, in his five major campaigns and battles of 1862–63, he commanded a cumulative total of 220,970 soldiers, of whom 23,551 (10.7 percent) were killed or wounded. Second, they determined that, in his eight major campaigns and battles of 1864– 65 (when he was determined to defeat or destroy Lee’s army as quickly as possible), he commanded a cumulative total of 400,942 soldiers, of whom 70,620 (17.6 percent) were killed or wounded. Third, they determined that during the course of the war, therefore, he commanded a cumulative total of 621,912 soldiers in his major campaigns and battles, of whom a total of 94,171 (a militarily tolerable 15.1 percent) were killed or wounded. These loss percentages are remarkably low—especially considering that General Grant was on the strategic and tactical offensive in most of these battles and campaigns.

We can put these numbers in perspective by comparing them with the casualty figures for the Army of Northern Virginia under Lee’s command and with those for other Confederate commanders. During the course of the war, Lee, in his major campaigns and battles, commanded a cumulative total of 598,178 soldiers, of whom 121,042 were killed or wounded—a total loss of 20.2 percent, about one-third higher than Grant’s. Other major Confederate commanders with higher percentages killed or wounded than General Grant were Generals Braxton Bragg (19.5 percent), John Bell Hood (19.2 percent), and Pierre Gustave Tousant Beauregard (16.1 percent) at Wilderness and Spotsylvania combined). Given the number of battles his armies fought, this is a surprising but informative result.

Far from being the butcher of the battlefield, General Grant determined what the North needed to do to win the war and did it. His record of unparalleled success—including Forts Henry and Donelson, Shiloh, Port Gibson, Raymond, Jackson, Champion’s Hill, Vicksburg, Chattanooga, the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Court House, Petersburg, and Appomattox—establishes him as the greatest general of the Civil War.

John Keegan has studied the leading generals of the Civil War and concluded, “Grant was the greatest general of the war, one who would have excelled at any time in any army. He understood the war in its entirety and quickly grasped how modern methods of communication . . . had endowed the commander with the power to collect information more quickly and the means to disseminate appropriate orders in response.”

A brief examination of General Grant’s battles and campaigns will enable readers to draw their own conclusions about how successful General Grant was and whether the casualties his armies incurred were reasonable.

Would you like to learn the complete history of the Civil War? Click here for our podcast series Key Battles of the Civil War

Would you like to learn the complete history of the Civil War? Click here for our podcast series Key Battles of the Civil War

Cite This Article

"Getting to Know the Other Side of General Grant" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

July 27, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/getting-to-know-general-grant>

More Citation Information.