Grant and Lee’s Civil War Strategy: Vision

National Perspective/Grand Civil War Strategy

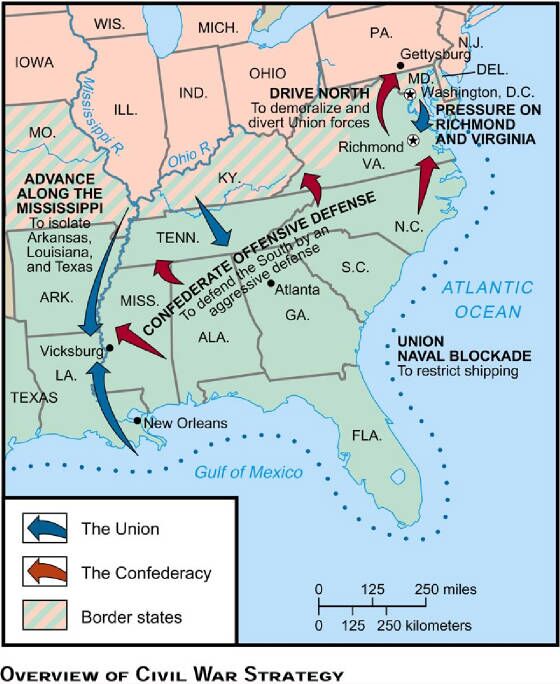

While Robert E. Lee was strictly a Virginia-focused, one-theater commander who constantly sought reinforcements for his theater and resisted transfers to other theaters, Grant had a broad, national perspective, rarely requested additional troops from elsewhere, and uncomplainingly provided reinforcements to locations, not under his command. Contrasting examples of their approaches are Lee’s retention of Longstreet for his Gettysburg campaign, Lee’s delay of Longstreet’s transfer to Chickamauga, Lee’s maneuvering to get Longstreet back to Virginia from Chattanooga, Grant’s cooperation in sending reinforcements to Buell in Kentucky to oppose Bragg in late 1862, Grant’s numerous proposals for campaigns against Mobile, and his war-winning, multi-theater strategic plan for operations beginning in May 1864. J. F. C. Fuller concluded, “Unlike Grant, [Lee] did not create a strategy in spite of his Government; instead, by his restless audacity, he ruined such strategy as his Government created.”

Critical to Grant’s success and Union victory in the war was that Grant early in the war recognized the need to focus, and thereafter stayed focused, on defeating, capturing, or destroying opposing armies. He di \ not simply occupy Fort Donelson, Vicksburg, and Richmond. Instead, he maneuvered his troops in such a way that he captured enemy armies in addition to occupying important locations. Unlike McClellan, Hooker, and Meade, who ignored Lincoln’s admonitions to pursue and destroy enemy armies, and Halleck, who was satisfied with his hollow capture of Corinth, Grant believed in and practiced that approach, which was so critical to Union victory.

Grant’s armies incurred the bulk of their casualties in the Overland Campaign of 1864. In Gordon C. Rhea’s words, “[t]he very nature of Grant’s [offensive] assignment guaranteed severe casualties.” Although Meade’s Army of the Potomac, under the personal direction of Grant, did suffer high casualties that year during its drive to Petersburg and Richmond, it imposed an even higher percentage of casualties on Lee’s army. In addition, that federal army compelled Lee to retreat to a nearly besieged position at Richmond and Petersburg, which Lee had previously said would be the death knell of his own army. Rhea concluded, “A review of Grant’s Overland Campaign reveals not the butcher of lore, but a thoughtful warrior every bit as talented as his Confederate opponent.” At the same time as he advanced on Lee’s army and Richmond, Grant was overseeing and facilitating a coordinated attack against Confederate forces all over the nation, particularly Sherman’s campaign from the Tennessee border to Atlanta.

As he had hoped, Grant succeeded in keeping Lee from sending reinforcements to Georgia, Sherman’s capture of Atlanta virtually ensured the crucial reelection of Lincoln, and Sherman ultimately broke loose on a barely contested sweep through Georgia and the Carolinas that doomed the Confederacy. Grant’s 1864–65 nationwide coordinated offensive against the Rebel armies, as stated before, not only won the war but demonstrated that he was a national general with a broad vision.

Nevertheless, all too often Grant has been regarded as a “hammerer and a butcher who was often drunk, an unimaginative and ungifted clod who eventually triumphed because he had such overwhelming superiority in numbers that he could hardly avoid winning.” Although the Overland Campaign proved costly to the Army of the Potomac, it was fatal for Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Grant took advantage of the fact that Lee had gravely weakened his outnumbered army in 1862 and 1863 and successfully conducted a campaign of adhesion against Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. As Rhea concluded, Grant provided the backbone and leadership that the Army of the Potomac had been lacking:

. . . it was a very good thing for the country that Grant came east. Had Meade exercised unfettered command over the Army of the Potomac, I doubt that he would have passed beyond the Wilderness. Lee would likely have stymied or even defeated the Potomac army, and Lincoln would have faced a severe political crisis. It took someone like Grant to force the Army of the Potomac out of its defensive mode and aggressively focus it on the task of destroying Lee’s army.

Historian Jeffry Wert described how Grant’s Civil War strategy vision and perseverance (see above) combined to reinforce each other: “On May 4, 1864, more than a quarter of a million Union troops marched forth on three fronts. There would be no turning back this time. This time, a strategic vision guided the movements, girded by an iron determination—the measure of Ulysses S. Grant’s greatness as a general.” Williamson Murray saw the same traits: “Ulysses Simpson Grant was successful where other union generals failed because he took the greatest risks and followed his own vision of how the war needed to be won, despite numerous setbacks.”

According to historian T. Harry Williams, Lee, unlike Grant, had little interest in a global Civil War strategy for winning the war, and:

What few suggestions [Lee] did make to his government about operations in other theaters than his own indicate that he had little aptitude for grand planning… Fundamentally Grant was superior to Lee because in a modern total war he had a modern mind, and Lee did not… The modernity of Grant’s mind was most apparent in his grasp of the concept that war was becoming total and that the destruction of the enemy’s economic resources was as effective and legitimate a form of warfare as the destruction of his armies.

Lee’s Civil War strategy concentrated all the resources he could obtain and retain almost exclusively in the eastern theater of operations, while fatal events were occurring in the Mississippi Valley and middle theaters (primarily in Tennessee, Mississippi, Georgia, and the Carolinas). His approach overlooked the strength of the Confederacy in its size and lack of communications, which required the Union to conquer and occupy it.

Historian Archer Jones provided an analysis tying together Lee’s two strategic weaknesses (aggressiveness and Virginia myopia): “More convincing is the contention that if the Virginia armies were strong enough for an offensive they were too strong for the good of the Confederacy. They would have done better to spare some of their strength to bolster the sagging West where the war was being lost.”

Lee’s solitary focus on Virginia should not have been surprising. After declining command of the Union’s armies at the start of the war, Lee immediately resigned his U.S. military commission and assumed command of the Virginia militia. When he did so, he stated, “I devote myself to the service of my native State, in whose behalf alone will I ever again draw my sword.” His “Virginia parochialism” hampered the South during the entire war. To the detriment of the

Confederacy, Lee was a Virginian first and a Confederate second. This trait was harmful, even though he was not the commander-in-chief, due to his crucial role as Davis’ primary military advisor throughout the war.

Even more significantly, Lee’s actions played a role in major Confederate western defeats at Vicksburg, Tullahoma, Chattanooga, and Atlanta. He refused to send reinforcements before or during Grant’s campaign against Vicksburg; contributed to the gross undermanning of the Confederate forces during the Tullahoma Campaign and at Chattanooga ; and played a critical role in the disastrous ascension of Hood to command in the West that led to the fall of Atlanta and the destruction of the Army of Tennessee.

Throughout the war, Lee was obsessed with operations in Virginia and urged that additional reinforcements be brought to the Old Dominion from the West, where Confederates defended ten times the area in which Lee operated. Thomas L. Connelly and Archer Jones concluded that “Lee actually supplied little general strategic guidance for the South. He either had no unified view of grand Civil War strategy or else chose to remain silent on the subject.” Often Lee prevailed upon President Jefferson Davis to refuse or only partially comply with requests to send critical reinforcements to the West.

In April 1863, for example, Lee opposed sending any of his troops to Tennessee even though the Union had sent Burnside’s 9th Corps there. Using arguments that one of his supporters called bizarre, Lee opposed concentration against the enemy and favored concurrent offensives by all Confederate commands against their superior foes. Lee used similar arguments the next month when he declined to involve his soldiers in an effort to save Vicksburg (and a

Confederate army of 30,000) and thereby prevent Union control of the Mississippi River. In addition, the lack of eastern reinforcements caused Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee to retreat in the mid-1863 Tullahoma Campaign from middle Tennessee through Chattanooga into Georgia, thereby losing Tennessee and the vital rail connection between northern Alabama and southern Tennessee in the “West” and Richmond and other eastern points.

Only once, in late 1863, did Lee consent to a portion of his army being sent west. On that occasion, Lee delayed those troops’ departure from Virginia for over two weeks and caused many of them to arrive only after the Battle of Chickamauga—and without their artillery. Despite Lee’s non-support, the barely reinforced Rebels won at Chickamauga and drove the Yankees back into Chattanooga. Lee’s delays, however, had deprived the Rebels of perhaps an additional 10,000 troops and the artillery that might have destroyed, rather than merely repelled, Rosecrans’ Army of the Cumberland. Nevertheless, that army was besieged and threatened by starvation in Chattanooga. Almost immediately, however, Lee undercut his grudging assistance by promoting the prompt return to him of his Virginia troops. His promotion of Longstreet’s return led to movement of Longstreet’s 15,000 troops away from Chattanooga just before the Union forces broke out of Chattanooga against Bragg’s vastly outnumbered army.

Lee compounded his erroneous Civil War strategy to the West by acquiescing in the disastrous elevation of his protégé, the obsessively aggressive John Bell Hood, to full general and command of the Army of Tennessee at the very moment Sherman reached Atlanta in July 1864. Within seven weeks Hood lost Atlanta, and within six months he destroyed that army. During that significant summer, Lee squandered Jubal Early’s 18,000-man corps on a demonstration against Washington instead of sending those troops to Atlanta, where they could have played a vital role defending that city under the command of either Johnston or Hood. These events enabled Sherman to march unmolested through Georgia and the Carolinas and ultimately to pose a fatal backdoor threat to Lee’s own Army of Northern Virginia.

Some may question whether Lee’s Civil War strategy, that he should have sent troops to the “West,” where allegedly incompetent generals would have simply squandered them. There are several problems with that position. First, many of those western generals were so outnumbered (more than Lee was) that they were simply outflanked by their Union opponents (e.g., Bragg in mid-1863 and Johnston in mid-1864) in vast areas that afforded greater maneuverability than did Virginia. Second, Lee declined several opportunities to take command in the West, where he could have commanded troops moved from the East but where he had little interest and probably had an inkling things were more difficult than he knew or wanted to know. Third, the success of the few troops that Lee finally provided for Chickamauga demonstrated what might have been if Lee had sent more of Longstreet’s troops and done so in a timely manner. Fourth, Jubal Early’s corps could have provided invaluable assistance in preventing the fall of Atlanta prior to the crucial 1864 presidential election. Finally, Lee himself squandered troops in the East (particularly at Seven Days’, Chancellorsville, Antietam, and Gettysburg), lost the war doing what he did, and could hardly have done worse sending some troops to the undermanned “West.”

In summary, through his own Civil War strategy, Grant won the Mississippi theater, saved the Union Army in the middle theater, and then won the eastern theater and the war. Lee lost the eastern theater and adversely affected Confederate prospects in the other theaters. How important were those other theaters (often referred to collectively as “the West”)? Richard McMurry, after arguing that Lee was justified in his actions, conceded: “Finally, it seems that, as the Civil War evolved, the really decisive area—the theater where the outcome of the war was decided —was the West. The great Virginia battles and campaigns on which historians have lavished so much time and attention had, in fact, almost no influence on the outcome of the war. They led, at most, to a stalemate while the western armies fought the war of secession to an issue.” Weigley criticized Lee’s failure to appreciate the significance of Tennessee as the South’s primary granary and meat source, as well as the importance of the mines, munitions plants, manufacturing, and transportation facilities in Georgia and Alabama. Grant’s national perspective prevailed while Lee’s myopic views badly hurt the Confederacy.

Civil War Strategy: Political Common Sense

Unlike McClellan, Beauregard, Joseph Johnston, and many other Civil War generals, Grant made it his business to get along with his president. In the words of Thomas Goss, “Unlike many of his fellow commanders, Grant was willing to support the political goals of the administration as they were presented to him.” That cooperation included tolerating political generals, such as McClernand, Sigel, Banks, and Butler until Grant had given them enough rope to hang themselves. Michael C. C. Adams explained Grant’s willingness to work with Lincoln: “Grant’s freedom from acute awareness of class may also partially explain his excellent working relationship with Lincoln. Grant was one of the few top generals who managed to avoid looking down on the common-man president. He took his suggestions seriously and benefited accordingly.” Grant’s loyalty was rewarded when Lincoln allowed him to designate colonels and generals for promotion and to remove the remaining unsuccessful political generals—especially after Lincoln’s 1864 reelection.

Grant extended his cooperative attitude to Stanton, who reciprocated by directing his staff officers to comply with Grant’s wishes. Grant’s political antennae also kept him from “retreating” back up the Mississippi River to begin a fresh campaign against Vicksburg in the spring of 1863 or moving back toward Washington after 1864 Overland Campaign “setbacks” because of the negative public reaction and morale impact such regressive movements would provoke among his soldiers and the public.

Lee was similar to Grant in his cultivating an excellent working relationship with his president. Lee’s war-long correspondence with Davis virtually drips with deference—a deference that the ultrasensitive Davis appreciated and reciprocated. It was partially Lee’s circumspect politeness to Davis that resulted in the sharp contrast between the DavisLee relationship and those between Davis and Joseph Johnston and P. G. T. Beauregard. Lee had great influence on Davis; they had none.

This article is part of our larger selection of posts about the Civil War. To learn more, click here for our comprehensive guide to the Civil War.

Cite This Article

"Grant and Lee’s Differing Civil War Strategy" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

April 24, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/grant-and-lees-winning-civil-war-strategy>

More Citation Information.