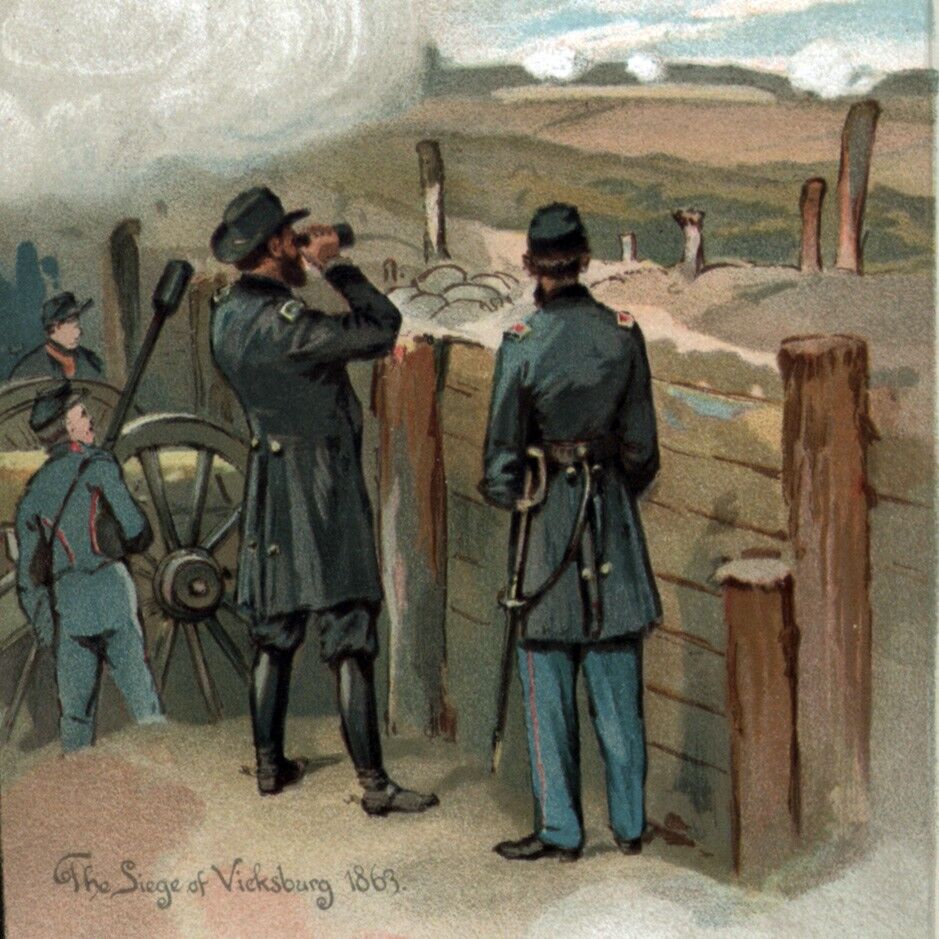

Grant’s Vicksburg campaign during the American Civil War was the last major military attack led by Union Maj. Gen. Ulysses and Tennesse Army who crossed Mississipi River on May 18-July 4, 1863.

GRANT’S VICKSBURG CAMPAIGN

During the spring and early summer of 1863, Grant carried out what James M. McPherson has called “the most brilliant and innovative campaign of the Civil War” and T. Harry Williams has called “one of the classic campaigns of the Civil War and, indeed, of military history.” In fact, the U.S. Army Field Manual 100-5 (May 1986) describes the Vicksburg campaign as “the most brilliant campaign ever fought on American soil,” one which “exemplifies the qualities of a well-conceived, violently executed offensive plan.”

Vicksburg, the Gibraltar of the West, was the key to Union control of the Mississippi. Along with Port Hudson to the south, it was the only remaining Confederate stronghold on the river. Early in the war, Lincoln himself had stressed Vicksburg’s importance when, pointing to a national map, he said, “See what a lot of land these fellows hold, of which Vicksburg is the key. The war can never be brought to a close until that key is in our pocket.”

Having been stymied in his earlier efforts to capture Vicksburg, Grant decided to march his army southward down the west bank of the Mississippi to get well below it. He planned to lead his men on transports that would first have to be floated past the city’s guns, transport his army to the Mississippi shore south of Vicksburg, strike inland against any Confederate forces they might meet, and eventually capture Vicksburg. He had spent months poring over maps and charts as he single-handedly devised this approach. His strong subordinate commanders—including

Sherman, James B. McPherson, and John “Black Jack” Logan—opposed the plan as too risky. Vicksburg was heavily fortified, but Grant’s plan proved spectacularly effective. Surrounded by nine major forts or citadels, the city was protected by 172 guns commanding all approaches by water and land and a thirty-thousand-troop garrison. Grant had three options for attacking it: (1) return to Memphis for an overland approach from the north and east, (2) cross the river and directly assault the city, or (3) march his troops down the west bank of the Mississippi, cross it, and approach the city from the south and east. Grant rejected the first option because going back would be morale-deflating (Grant hated to retrace his steps). He rejected the second because it involved, he said, “immense sacrifice of life, if not defeat.” “The third alternative was full of dangers and risks,” the Vicksburg historian Edwin C. Bearss has said. “Failure in this venture would entail little less than total destruction. If it succeeded, however, the gains would be complete and decisive.”

Early April brought receding waters and the emergence of roads from Milliken’s Bend northwest of Vicksburg to other points down-river on the west bank. Grant planned to march his troops over those roads to a location where he could ferry them to the east bank of the river. He enlisted the support of Admiral David Porter, who moved steamships and transport vessels from north of Vicksburg down to where Grant’s troops would be awaiting transportation across the river.

The cooperative Porter agreed to Grant’s plan and eagerly set about organizing the vessels for a maritime parade past Vicksburg. He warned Grant that as the ironclad vessels did not have sufficient power to return upstream past Vicksburg’s guns, this transit would be the point of no return. In preparation for the transit, Porter directed that boilers on the steamships be hidden and protected by barriers of cotton and hay bales, as well as bags of grain. The hay and cotton would also be useful later. Beginning at ten o’clock on the evening of April 16, Porter led the fleet of seven ironclad gunboats, four steamers, the tug Ivy, and an assortment of towed coal barges downstream. Coal barges and excess vessels were lashed to the sides of critical vessels to provide additional protection. Confederate bonfires illuminated the Union vessels, which were under fire for two hours as they ran the gauntlet past the Vicksburg guns. Those guns fired 525 rounds and scored sixty-eight hits. Miraculously, only one vessel was lost, and no one on the vessels was killed their intended operations and the single line of march was inadequate to supply his troops, Grant ordered a second collection of vessels to bring some additional supplies south past

Vicksburg. Thus, on the night of April 22, six more protected steamers towing twelve barges loaded with rations steamed past Vicksburg under the command of Colonel Clark Lagow of Grant’s staff. Despite General Lee’s prediction, five of the steamers and half of the barges made it through the gauntlet of artillery batteries, which fired 391 rounds. Most of the vessels were commanded and manned by army volunteers from “Black Jack” Logan’s division because the civilian vessel crews were afraid to run the Vicksburg gauntlet.

Grant now had his transportation (seven transports and fifteen or sixteen barges), a modicum of supplies, and a gathering invasion force. Sherman and Porter had serious doubts about the feasibility of transporting the supplies for Grant’s army down a poor, swampy road on the west bank of the Mississippi River, across the water, and into Mississippi. Nevertheless, Grant pressed forward with his plan and started McPherson’s corps south from New Carthage on April 25.

Meanwhile, Grant had created four diversions to the north and east of Vicksburg to deflect Confederate attention away from his planned campaign. First, he had sent Major General Frederick Steele’s troops in transports one hundred miles northward up the Mississippi River toward Greenville, Mississippi. Concluding that Grant was retreating (to reinforce William Rosecrans in eastern Tennessee), Pemberton allowed about eight thousand rebel troops to be transferred from Mississippi back to Bragg in Tennessee.

Second, Grant had initiated a cavalry raid from Tennessee to Louisiana through the length of central and eastern Mississippi. Incurring only a handful of casualties, Colonel Benjamin H. Grierson, a fellow Illinoisan, conducted the most successful Union cavalry raid of the entire war. Grant had devised this diversionary mission back on February 13, when he sent the following simple, flexible, and brilliant suggestion in a dispatch to General Hurlbut in Tennessee:

It seems to me that Grierson with about 500 picked men might succeed in making his way South and cut the rail-road East of Jackson Miss. The undertaking would be a hazardous [sic] one but it would pay well if carried out. I do not direct that this shall be done but leave it for a volunteer enterprise.

On April 17, Grierson rode out of LaGrange, Tennessee, in command of 1,700 cavalrymen and a six-gun battery. In the early days of the raid, he deftly split off part of his force, primarily to confuse the Confederates as to his location and intentions. First, on April 20, he sent 175 men determined to be incapable of completing the mission (the “Quinine Brigade”) and a gun back to LaGrange with prisoners and captured property. The next day he sent a regiment and another gun east to break up the north-south Mobile & Ohio Railroad and to stir up even more confusion. To determine whether substantial enemy forces were present in the towns he intended to raid, Grierson assembled a group of nine hand-picked men, the “Butternut Guerillas,” who scouted ahead dressed in Confederate uniforms and clothes.

With still another thirty-five-man detached force drawing substantial Confederate infantry and cavalry away from his main force, Grierson continued to Newton on the east-west Southern Railroad (the eastern extension of the Vicksburg and Jackson Railroad) in the heart of Mississippi. There, on the 24th, he destroyed two trains (both filled with ammunition and commissary stores). He also tore up the railroad and tore down the telegraph line—both linking Meridian with Jackson and Vicksburg to the west. With the disruption of the key railroad to Vicksburg and the destruction of millions of dollars’ worth of Confederate assets (including thirty-eight rail cars), Grierson’s mission was complete—except for his final escape.

Pemberton, who had sent troops to head off Grierson before he reached the railroad, now sent additional soldiers to try to cut off the escape of his raiders.The raid’s effect on Pemberton was precisely what Grant intended—on April 27 he sent seventeen messages to Mississippi commands about Grierson’s raiders and not a single one about Grant’s build-up on the west bank of the Mississippi. By the 29th, Pemberton had further played into Grant’s hands by sending all his cavalry in pursuit of Grierson and advising his superiors, “The telegraph wires are down. The enemy has, therefore, either landed on this side of the Mississippi River, or they have been cut by Grierson’s cavalry. . . . All the cavalry I can raise is close on their rear.”

Sixteen days and six hundred miles after starting their dangerous venture, Grierson’s men reached the Union lines at Baton Rouge, Louisiana, on May 2—three days after Grant’s amphibious landing at Bruinsburg on the Mississippi. They had survived several close calls, left havoc in their wake, and accomplished their primary mission of diverting attention from Grant’s movements west and south of Vicksburg. They had inflicted one hundred casualties and captured over five hundred prisoners. Miraculously, all this had been accomplished with fewer than twenty-five casualties. There was a good reason for Sherman to call it the “most brilliant expedition of the Civil War.”

Grant’s third diversion involved another cavalry foray. While Grierson was traveling the length of Mississippi, other Union forces went on the offensive far to the east. Colonel Abel D. Streight led a “poorly mounted horse and mule brigade” from middle Tennessee into Alabama and drew the ever-dangerous cavalry of Nathan Bedford Forrest away from Grierson and his various detachments.

To completely confuse Pemberton, Grant employed the fourth diversion. While he was moving south with McClernand and McPherson on the west (Louisiana) bank, Grant had Sherman’s Fifteenth Corps threaten Vicksburg from the north. On April 27, Grant ordered Sherman to proceed up the Yazoo River and threaten Snyder’s Bluff northeast of Vicksburg. On the 29th, Sherman debarked ten regiments of troops and appeared to be preparing an assault while eight naval gunboats bombarded the Confederate forts at Haines’s Bluff. Having suffered no casualties, Sherman withdrew on May 1 and hastily followed McPherson down the west bank of the Mississippi. His troops were ferried across the river on May 6 and 7.

Grant, meanwhile, had joined McClernand at New Carthage on the west bank on April 23. When Colonel James H. Wilson of Grant’s staff and Admiral Porter determined that there were no suitable landing areas east of Perkins’s Plantation, Grant on April 24 ordered the troops to proceed south another twenty-two miles to Hard Times, a west bank area sixty-three miles south of Milliken’s Bend and directly across the river from Grand Gulf, Mississippi. According to Secretary of War Stanton’s special observer, the former New York Tribune reporter, and editor Charles A. Dana, McClernand moved his troops slowly and disobeyed Grant’s orders to preserve ammunition and to leave all impediments behind. Instead, he had guns fired in a salute at a review and tried to bring his wife and servants along. Ten thousand soldiers were moved farther south by vessel, and the rest of the men bridged three bayous and completed their trek to Hard Times by April 27. On April 28, Confederate Brigadier General John S. Bowen at Grand Gulf could see the Union armada gathering across the river and urgently requested reinforcements from Pemberton in Vicksburg. Focused on Grierson and Sherman, however, Pemberton refused to send reinforcements south toward Grand Gulf until late on April 29, when they were too late to halt the amphibious crossing.

Two days later, with ten thousand of McClernand’s troops embarked on vessels for a possible east bank landing, Porter’s eight gunboats attacked the Confederate batteries on the high bluffs at Grand Gulf. After five and a half hours and the loss of eighteen killed and about fifty-seven wounded, the Union fleet had eliminated the guns of Fort Wade but not those of Fort Coburn, which stood forty feet above the river and was protected by a forty-foot-thick parapet. A disappointed Grant watched from a small tugboat, and Porter eventually halted the attack.

Grant, however, did not give up; he simply moved south. That night, ten thousand troops left the vessels and marched across a peninsula while Porter slipped all of his vessels past the Confederate guns. Grant was planning to load his troops again and land them at Rodney, about nine miles south of Grand Gulf. He changed his mind, though, when a local black man told a landing party that Bruinsburg, a few miles closer, offered a good landing site and a good road inland to Port Gibson. Convinced of what he was going to do the next day, Grant sent orders that night to Sherman to head south immediately with two of his three divisions. On the morning of April 30, Grant moved down and across the Mississippi with McClernand’s corps and one of McPherson’s divisions from Disharoon’s Plantation (near Hard Times), Louisiana. He then took them six miles south to Bruinsburg, Mississippi, and landed them without opposition. In his memoirs, Grant explained the great relief he felt after the successful landing:

When this was effected I felt a degree of relief scarcely ever equaled since. Vicksburg was not yet taken it is true, nor were its defenders demoralized by any of our previous moves. I was now in the enemy’s country, with a vast river and the stronghold of Vicksburg between me and my base of supplies. But I was on dry ground on the same side of the river with the enemy. All the campaigns, labors, hardships and exposures from the month of December previous to this time that had been made and endured, were for the accomplishment of this one object.

Under the cover of several diversions, Grant had daringly marched his army through Louisiana bayous down the west bank of the Mississippi and launched a huge amphibious operation involving twenty-four thousand troops. The historian Terrence J. Winschel writes admiringly:

The movement from Milliken’s Bend to Hard Times was boldly conceived and executed by a daring commander willing to take risks. The sheer audacity of the movement demonstrated Grant’s firmness of purpose and revealed his many strengths as a commander. The bold and decisive manner in which he directed the movement set the tone for the campaign and inspired confidence in the army’s ranks.

This article is part of our larger selection of posts about the Civil War. To learn more, click here for our comprehensive guide to the Civil War.

This article is also part of our extensive collection of articles on Black History in the United States. Click here to see our comprehensive article on Black History in the United States.

Would you like to learn the complete history of the Civil War? Click here for our podcast series Key Battles of the Civil War

Cite This Article

"Grant’s Vicksburg Campaign- Crossing the Mississippi River" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

July 25, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/grant-vicksburg>

More Citation Information.