LINCOLN WINS ELECTION OF 1864 WITH GRANT’S FULL SUPPORT

In 1864, Lincoln once again demonstrated a political aggressiveness that matched Grant’s military aggressiveness. In that year’s political campaign, he, along with Republican Radicals, insisted that the Republican platform contain a plank advocating a constitutional amendment abolishing slavery. He encouraged his secretary of war to work with his generals to allow as many soldiers from non-absentee-ballot states as possible to return home to vote for president.

But the election of 1864 results, especially before the fall of Atlanta, were not pre-ordained. Lincoln was vulnerable because the North was divided on the issues of war, the draft, and slavery. There had been draft riots in New York City, anti-war “Copperhead” sentiment flourished in the Midwest, and the Democrats adopted a peace platform at their convention. Just after McClellan’s nomination, Secretary of the Navy Welles worried that “McClellan will be supported by War Democrats and Peace Democrats, by men of every shade and opinion; all discordant elements will be made to harmonize, and all differences will be suppressed.” The next day, however, he took a contrary position: “Notwithstanding the factious and petty intrigues of some professed friends . . . and much mismanagement and much feeble management, I think the President will be reelected, and I shall be surprised if he does not have a large majority.”

As Archer Jones observed, “Increasingly, Confederate leaders and people, including the soldiers, looked to the Union presidential election of 1864 as the crucial time when the North could have a referendum on whether or not to continue the war.” As early as May 1863, Confederate Chief of Ordnance Josiah Gorgas noted in his diary the vulnerability of the North to political defeat: “No doubt that the war will go on until at least the close of [Lincoln’s] administration. How many more lives must be sacrificed to the vindictiveness of a few unprincipled men! For there is no doubt that with the division of sentiment existing at the North the administration could shape its policy either for peace or for war.”

As the armies looked ahead to the crucial campaigns of 1864, Confederate Lieutenant General Longstreet on March 27 prophetically wrote, “Lincoln’s re-election seems to depend upon the result of our efforts during the present year. If he is re-elected, the war must continue, and I see no way of defeating his re-election except by military success.”

Longstreet also saw the connection between Grant’s progress, or lack thereof, in the 1864 campaigns and the election: “If we can break up the enemy’s arrangements early, and throw him back, he will not be able to recover his position or his morale until the Presidential election is over, and then we shall have a new President to treat with.”

During the summer of 1864, many Northerners were upset by the Army of the Potomac’s numerous casualties, as its soldiers carried out their Overland Campaign from the Rappahannock River across the James River. Ever attacking, they suffered mounting losses at the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Court House, the North Anna River, Cold Harbor, and Petersburg.

Union casualty names and statistics were being published daily in Northern newspapers. In addition, many Northerners were frustrated by the failure of Union armies to capture either Richmond or Atlanta Newspaper editors and Republican Party leaders urged Lincoln not to run again—to step aside for someone who could win. New York editor Horace Greeley wrote, “Mr. Lincoln is already beaten. He cannot be elected.” In July he asked Lincoln to open peace negotiations with the Confederacy because “our bleeding, bankrupt, almost dying country longs for peace.” Then in August, shrewd and powerful New York politico Thurlow Weed said, “The people are wild for peace… Lincoln’s reelection an impossibility.”

Lincoln himself was doubtful about his election of 1864 prospects. That August he told a friend, “You think I don’t know I am going to be beaten, but I do and unless some great change takes place, badly beaten.” In fact, on August 23 Lincoln reduced his pessimism to writing. At a cabinet meeting, he produced a piece of paper on which he had written: “This morning, as for some days past, it seems exceedingly probable that this administration will not be re-elected. Then it will be my duty to so cooperate with the President-elect, as to save the Union between the election and the inauguration; as he will have secured his election on such ground that he cannot possibly save it afterward.” Without disclosing those words to his cabinet members, he had seven of them sign the document on the reverse side as evidence of the date of his words.

On November 11, a few days after the presidential election of 1864, Lincoln, at last, read those words to his cabinet after John Hay had cut the sealed document open. He then went on, according to Hay’s diary, to explain his mindset at that time:

[Y]ou will remember that this was written at a time [6 days before the Chicago nominating convention] when as yet we had no adversary and seemed to have no friends. I then solemnly resolved on the course of action indicated above. I resolved, in case of the election of General McClellan being certain that he would be the Candidate, that I would see him and talk matters over with him. I would say, “General, the election of 1864 has demonstrated that you are stronger, have more influence with the American people than I. Now let us together, you with your influence and I with all the executive power of the Government, try to save the country. You raise as many troops as you possibly can for this final trial, and I will devote all my energies to assisting and finishing the war.”

In response, Secretary Seward said, “And the General would answer you ‘Yes, Yes’; and the next day when you saw him again & pressed these views upon him he would say ‘Yes—yes’ & so forever and would have done nothing at all.” And Lincoln concluded, “At least I should have done my duty and have stood clear before my own conscience.”

Back in August, Lincoln’s prospects looked dim. On August 22 Weed wrote to Seward, “When, ten or eleven days since, I told Mr. Lincoln that his re-election was an impossibility, I also told him that the information would soon come to him through other channels. It has doubtless, ere this, reached him. At any rate, nobody here doubts it; nor do I see anybody from other States who authorises the slightest hope of success.”

Probably in coordination with Weed, Henry J. Raymond, Republican National Chairman and New York Times editor and owner, wrote to Lincoln about his reelection prospects. He painted a gloomy nationwide picture:

I feel compelled to drop you a line concerning the political condition of the country as it strikes me. I am in active correspondence with your staunchest friends in every state and from them all I hear but one report. The tide is setting strongly against us. Hon. E. B. Washburne writes that ‘were there an election of 1864 to be held now in Illinois we should be beaten.’ Mr. Cameron writes that Pennsylvania is against us. Gov. Morton writes that nothing but the most strenuous efforts can carry Indiana. This state [New York], according to the best information I can get, would go 50,000 against us tomorrow. And so of the rest. Nothing but the most resolute and decided action on the part of the government and its friends can save the country from falling into hostile hands.

As late as September 2, Greeley and two other New York newspaper editors appealed to Northern governors to support a movement to replace Lincoln with another candidate.14 John Waugh noted, “The cantankerous James Gordon Bennett at the . . . New York Herald incessantly beat the drum for General Grant, who incessantly denied that he was a candidate.”15 Perhaps affected by all these negative reports, the president was working with black leader Frederick Douglass in an effort to inform as many slaves as possible of the Emancipation Proclamation and the possible need to seek freedom before McClellan could be elected president and cancel the proclamation.

Lincoln’s dim reelection prospects brought hope to Confederates. For example, on August 26, Jedediah Hotchkiss, Stonewall Jackson’s famed cartographer, wrote to his wife, “The signs are brightening, and I still confidently look for a conclusion of hostilities with the ending of ‘Old Abe’s’ reign.”17 McPherson concluded: “If the election had been held in August 1864 instead of November, Lincoln would have lost. He would thus have gone down in history as an also-ran, a loser unequal to the challenge of the greatest crisis in the American experience.”

At their Chicago convention, the Democrats adopted a peace platform that spoke of “four years of failure” and called for a halt of fighting “with a view to an ultimate convention” to resolve the major issues dividing the nation. Especially after the fall of Atlanta, McClellan was compelled to back off from what too many would deem an unacceptable surrender to the South. Thus he issued a September 9 letter setting forth his position; he rejected the “four years of failure” language, but he conceded that, when the Southern states were interested in returning to the Union on any terms, he would negotiate with them.

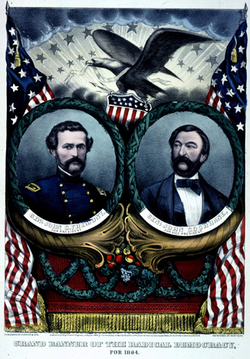

Democrats emphasized the issue of race. One of their campaign posters read: “ELECT LINCOLN and the BLACK REPUBLICAN TICKET. You will bring on NEGRO EQUALITY, more DEBT, HARDER TIMES, and another DRAFT! Universal Anarchy, and Ultimate RUIN! ELECT McCLELLAN and the whole Democratic Ticket. You will defeat NEGRO EQUALITY, restore Prosperity, reestablish the UNION! In an Honorable, Permanent and Happy PEACE.” Two Democratic editors published a spurious pamphlet, supposedly a Republican document that supported interracial marriage.

Late August was Lincoln’s nadir, but three military developments changed everyone’s perspective. The first was the fall of Mobile Bay, which was completed with the capture of Fort Morgan on August 26. The second was Phil Sheridan’s September and October defeats of Jubal Early and his destruction of the Confederate “breadbasket” in the Shenandoah Valley. Grant deserves much of the credit for the Shenandoah successes because he forcefully pushed Lincoln to approve Sheridan’s role and command there and he kept Lee occupied in order to prevent him from sending more troops to Early.

Final Key to Lincoln’s Win in Election of 1864

Finally, the third major event changing people’s attitudes and minds — the “great change” Lincoln needed for reelection—was the fall of Atlanta. Atlanta’s capture instantly changed Northern public opinion and suddenly made Lincoln a favorite to win reelection. Meanwhile, the Democrats had committed a major strategic error; they had postponed their own convention until the end of August in hopes of capitalizing on the high casualties and lack of success by Grant and Sherman. Instead, no sooner did they nominate McClellan on September 1 than Sherman took Atlanta and derailed McClellan’s campaign before it could start, let alone gain any momentum. Grant had contributed to Atlanta’s fall by maintaining- ing pressure on Lee to keep him from reinforcing the Confederates defending Atlanta. General Fuller emphasized the importance of these three military victories: “These battles were not only of great value to Grant in furthering the war but of immense importance to Lincoln in gaining his election, without which the war would in all probability have collapsed.”

Lincoln’s reelection was a critical, war-saving event. The Democratic platform called for a cease-fire prior to a convention of the states in order to restore the Union with all states’ rights, including slavery, guaranteed. Davis would have shunned a convention without a guarantee of Southern states’ independence, Washington would have been in a state of confusion, and the Thirteenth Amendment would have been in jeopardy. A “temporary” cease-fire likely would have become a permanent cessation of hostilities.

Even after the September 2 fall of Atlanta, some skepticism about Lincoln’s prospects continued. On September 10, the London Daily News correspondent wrote, “I think of Lincoln’s chances at this moment as five to three.”As late as October 17, his fellow Illinoisan, Congressman Washburne, wrote to Lincoln, “It is no use to deceive ourselves. . . . There is imminent danger of our losing the State.”

Most of the post-Atlanta news and views, however, were quite positive. Atlanta had fallen just before the state and congressional elections that preceded November’s presidential election of 1864. On September 13, Lincoln received word from Maine Republican chairman James G. Blaine of a great victory—embellished with a confident prediction: “The Union majority in Maine will reach 20,000. We will give you thirty thousand (30,000) in November.”24 About that same time, the president scribbled an electoral vote calculation that he would receive 172 votes, McClellan 66, and Frémont 7.25 It is unclear whether that prediction was his or someone else’s.

Taking no chances, Lincoln pressured military commanders to provide adequate leave for soldiers from Indiana and other states that did not allow absentee balloting so that they could presumably vote for their commander-in-chief.26 Three-quarters of the more than 250,000 troops who voted cast their ballots for Lincoln. On September 19, Lincoln urged Sherman to do anything he could “safely do” to allow Indiana soldiers to return home to vote in the October 11 state elections because of the effect those elections would have on the November election. He was responding to a petition from Indiana Governor Morton and others that he delay the draft and return 15,000 soldiers to Indiana before the state election. Lincoln refused to suspend the draft but told Sherman of the importance of the Indiana election: “. . . the loss of it . .. would go far towards losing the whole Union cause. The bad effect upon the Novem- ber election, and especially giving the State Government to those who oppose the war in every possible way, is too much to risk if it can possibly be avoided. . . . Indiana is the only important State, voting in October, whose soldiers cannot vote in the field. Anything you can safely do to let her soldiers, or any part of them, go home and vote at the State election, will be greatly in point. They need not remain for the Presidential election of 1864, but may return to you at once.” On September 26, Lincoln wrote to Rosecrans, then commanding in Missouri, to ensure that soldiers would be allowed to vote in Missouri and said, “Wherever the law allows soldiers to vote, their officers must allow it.”

Governor Morton was not the only politico who was recommending suspension of the 500,000-man draft of September 5 until after the election of 1864. These included Cameron of Pennsylvania and Chase of Ohio. Grant and Sherman provided rebuttals. Grant wrote, “A draft is soon over, and ceases to hurt after it is made. The agony of suspense is worse upon the public than the measure itself.” Sherman added, “If the President modifies [the draft] to the extent of one man, or wavers in its execution, he is gone forever; the army will vote against him.” Lincoln finally concluded, “What is the Presidency worth to me if I have no country?” and allowed the draft to proceed on schedule.

On October 10 and 11 Lincoln, personally and in writing, urged Secretary of the Navy Welles to facilitate vote-gathering visits to “Seamen and sailors” by Charles Jones, Chairman of the Union State Central Committee for the State of New York. Welles described in his diary a visit from Lincoln and Seward “relative to New York voters in the Navy. Wanted one of our boats to be placed at the disposal of the New York commission to gather votes in the Mississippi Squadron.” With Lincoln’s blessing, the request and cooperation were extended to the Union blockading squadrons. On October 11 and 12, the president asked for and received a report from Simon Cameron on the Pennsylvania congressional and state legislative voting of October 11.

Demonstrating the importance of the election of 1864 results to both of them, Lincoln shared information on state elections with Grant in an October 12 telegram: “Sec. Of War not being in, I answer yours about the election. Pennsylvania very close, and still in doubt on home vote. Ohio largely for us, with all the members of congress but two or three. Indiana largely for us. Governor, it is said by 15,000, and 8 [o]f the eleven members of congress. Send us what you may know of your army vote.”

Indiana’s reelected Governor Morton immediately urged Lincoln and Stanton to retain his state’s sick and wounded soldiers in Indiana until after the presidential election of 1864. Lincoln responded cautiously on October 13. He reminded the governor that Lincoln’s September 19 letter to Sherman had “said that any soldiers he could spare for October need not remain for November.” Although Lincoln said he thus could not press Sherman on the point, “All that the Sec. of War and Gen. Sherman feel they can safely do, I, however, shall be glad of.” Morton’s final plea stated, “It is my opinion that the vote of every soldier in Indiana will be required to carry this state for Mr. Lincoln in November. The most of them are sick and wounded and in no condition to render service and it is better to let them remain while they are here.”

On October 13, Lincoln himself created a two-column list of possible state-by-state results in the coming presidential election of 1864. By including New York, Pennsylvania, Illinois, and Maryland on the “Supposed Copper head Vote” side of his equation, he calculated that the Union/Republican electoral vote could be 117 (not counting the yet-to-be-admitted State of Nevada with its three electoral votes) and the Democratic/Copper head vote a scary 114. It appears that Lincoln may have been creating and analyzing a “worst-case” scenario for the next month’s election.

Although risking his relationship with the press during the sensitive election of 1864 season, he deferred to Grant on the issue of reporters’ access to “his” army. During the Overland Campaign, Grant, apparently at Meade’s request, had revoked passes for reporters, including those of William Swinton of the New York Times and William H. Kent of the New York Tribune. After Swinton’s pass had been restored by Meade, Kent applied to Lincoln on September 27 for similar treatment. The president referred the letter to Grant “for his consideration and decision.” After receiving negative endorsements from Meade and Hancock indicating that Kent had filed false and damaging reports about Hancock’s command, Grant denied the request: “The most liberal facilities are afforded to newspaper correspondents, but they cannot be permitted to misrepresent facts to the injury of the service. When they so offend their pass . . . is withdrawn. . . . In this case, there appears to have been a deliberate attempt to injure one of the best Generals [Hancock] and Corps in the service. I cannot, therefore, consent to Mr. Kent’s return to this army.”

While Lincoln was having no easy time getting reelected, Sherman reported that Lincoln’s Confederate counterpart was creating his own difficulties by conducting himself in an un-Lincolnesque manner. After Sherman reported Jeff Davis’s presence in Georgia on September 26, Lincoln speculated that “I judge that [Georgia Governor Joseph E.] Brown and [Confederate Vice President Alexander] Stephens are the objects of his visit.” There was no love lost between Davis and either of them. On September 28, Sherman responded, “I have positive knowledge that Jeff Davis made a speech at Macon on the 22nd. . . . It was bitter against [Joseph E.] Johnston & Govr Brown. The [Georgia] militia is now on furlough.”36 Unlike Lincoln, Davis was publicly criticizing both a general and a governor who were critical to his cause.

Even on electoral issues, Lincoln retained his sense of humor. Secretary Seward provided him with an October 15 letter from a “P. J. J.” in New York stating, “On the point of leaving I am told by a gentleman to whose statements I attach Credit, that the opposition Policy for the Presidential Campaign will be to ‘abstain from voting.’” Lincoln’s October 16 endorsement on the letter snapped, “More likely to abstain from stopping once they get at it until they shall have voted several times each.”

Three days later Lincoln addressed a more serious problem. In responding to a crowd celebrating the adoption of a new no-slavery Maryland constitution, he talked about speculation that he might try to ruin the government if not reelected or that the Democrats would seize the government if their candidate won. The president reassured the crowd:

I hope the good people will permit themselves to suffer no uneasiness on either point. I am struggling to maintain the government, not to overthrow it. I am struggling especially to prevent others from overthrowing it. I, therefore, say, that if I shall live, I shall remain President until the fourth of next March; and that whoever shall be constitutionally elected therefor in November, shall be duly installed as President on the fourth of March; and that in the interval I shall do my utmost that whoever is to hold the helm for the next voyage, shall start with the best possible chance to save the ship. This is due to the people both on principle, and under the constitution. Their will, constitutionally expressed, is the ultimate law for all. If they should deliberately resolve to have immediate peace even at the loss of their country, and their liberty, I know not the power or the right to resist them. . . . I may add that in this purpose to save the country and it’s [sic] liberties, no class of people seem so nearly unanimous [sic] as the soldiers in the field and the seamen afloat. Do they not have the hardest of it? Who should quail while they do not?

Not only was Lincoln confident of the military vote, but he was also not above using it to shame others into voting for him.

Even his October 20 Proclamation of Thanksgiving served the president’s political purposes. In it, he praised Almighty God for “many and signal victories over the enemy” and for “augment[ing] our free population by emancipation and by immigration.”

Lincoln stayed in touch with political operatives around the country, such as Alexander K. McClure of Pennsylvania. On November 5, three days before the election of 1864, McClure advised the president that he would carry the Pennsylvania “home [non-soldier] vote” by 5,000 to 10,000 or more. McClure added that he was “greatly encouraged by the conviction that your Election will be by a decisive vote, & give you all the moral power necessary for your high & holy trust.”

Meanwhile, on October 31 the president, in hopes of acquiring three more electoral votes, proclaimed Nevada a state. Not only was every electoral vote important to Lincoln, but so was every individual vote. Thus, on November 3, he wrote to Stanton, “This man wants to go home to vote. Sec. of War please see him.” As late as November 7, Lincoln personally issued a five-day pass to one Lieutenant A. W. White to visit Philadelphia and return to Washington.

To ensure an orderly election in Democrat-controlled New York, the scene of draft riots the prior year, the president sent Butler and Federal troops there. When the commander of the state militia challenged Federal authority relating to the election in New York in an October 29 order, Butler proposed to trump him with an equally bombastic order asserting Federal authority. After consultations with Stanton, Lincoln decided to forestall issuance of Butler’s order until its necessity was more apparent: “I think this might lie over till morning. The tendency of the order, it seems to me, is to bring on a collision with the State authority, which I would rather avoid, at least until the necessity for it is more apparent than it yet is.” Lincoln also sent Seward back to his home state of New York to keep an eye on election of 1864 matters.

Riding the wave of the Atlanta, Mobile Bay, and Shenandoah military victories, Lincoln convincingly won reelection. Out of slightly more than four million votes, Lincoln received 2,218,388 (55 percent) while McClellan garnered 1,812,807 (45 percent). These votes resulted in a smashing 212–21 electoral vote victory for Lincoln. Although these statistics seem to reflect a landslide, the election of 1864 was much closer than it appeared. The switch of a mere three-quarter of one percent of the votes (29,935 out of 4,031,195) in specific states would have given McClellan the ninety-seven additional electoral votes he needed to barely win with one hundred eighteen electoral votes. He could have picked up the huge states of Pennsylvania and New York—and their fifty-nine electoral votes—with a swing of fewer than 13,000 voters. The additional thirty-eight electoral votes he would have needed could have been found in any number of smaller states where he had significant percentages of the vote. Lincoln was right to have been concerned about his reelection prospects and would not have won without the positive military events that preceded the election of 1864.

In the twelve states where military ballots were counted separately, Lincoln received 78 percent of them (119,754 to 34,291)—compared with his 53 percent of the civilian vote in those states. The soldiers’ decision was a striking endorsement of the Lincoln/Grant approach to war—in sharp contrast to that of McClellan, under whose command many of them had served. Chester Hearn asserted that the military vote was decisive in Connecticut, New York, and Maryland (where that vote also was responsible for the passage of a new state constitution that banned slavery).

Aware of Lincoln’s great interest in the soldiers’ votes, Grant sent Stanton a November 9 telegram giving the following vote totals in the Army of the Potomac:

| State | Total Votes | Lincoln’s Majority | (Lincoln/McClellan) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Maine | 1,677 | 1,143 | 1,410/267 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| New Hampshire | 515 | 279 | 397/118 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vermont | 102 | 42 | 72/30 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Loading... Loading... | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rhode Island | 190 | 134 | 162/28 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pennsylvania (partial) | 11,122 | 3,494 | 7,308/3,814 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| West Virginia | 82 | 70 | 76/6 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ohio | 684 | 306 | 495/189 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wisconsin | 1,065 | 633 | 849/216 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Michigan | 1,917 | 745 | 1,331/586 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Maryland | 1,428 | 1,160 | 1,294/134 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| U.S. Sharpshooters | 124 | 89 | 106/18 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (Multi-state) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| New York | 305 | 113 | 209/96 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 19,211 | 8,208 | 13,709/5,502 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

These numbers reflect the Eastern soldiers’ support for Lincoln, Grant and their aggressive efforts to bring the war to a successful close.

The next day (November 10) Grant sent his congratulations to Lincoln via Stanton: “Enough now seems to be known to say who is to hold the reins of Government for the next four years. Congratulate the President for me for the double victory. The election of 1864 has passed off quietly, no bloodshed or rioit [sic] throughout the land, is a victory worth more to the country than a battle won. Rebeldom and Europe will so construe it.” A few days later, Grant told John Hay that he was impressed most by “the quiet and orderly character of the whole affair.”

Defeating Lincoln in 1864 had been the Confederacy’s best opportunity for victory. McClellan’s well-documented respect for Southern “property rights” could have led to some sort of settlement short of a total Union victory that included the abolition of slavery—and perhaps to a ceasefire and de facto Southern independence while the peace terms were being negotiated. In a study of the war, David Donald, Jean Baker, and Michael Holt concluded that “Lincoln’s re-election ensured that the conflict would not be interrupted by a cease-fire followed by negotiations, and in that sense was as important a Union victory as any on the battlefield….”

The closeness of that election of 1864 demonstrates how important it had been for Grant to launch an aggressive nationwide offensive only two months after he became the Union general-in-chief. Without the capture of Atlanta, victory in the Shenandoah Valley and the capture of Mobile Bay, Lincoln’s chances of reelection would have been slim to none.

In the wake of the election of 1864, Lincoln addressed two serenading groups on November 8 and 10 at the Executive Mansion. In the latter response, he proclaimed, “We cannot have free government without elections; and if the rebellion could force us to forego or postpone a national election, it might fairly claim to have already conquered and ruined us…. [The election] has demonstrated that a people’s government can sustain a national election of 1864, in the midst of a great civil war. Until now it has not been known to the world that this was a possibility.” Lincoln was making the same points Grant did in his wire of the same day. The president then spoke of the need to “reunite in a common effort, to save our country….”

This article is part of our larger selection of posts about the Civil War. To learn more, click here for our comprehensive guide to the Civil War.

This article is also part of our larger selection of posts about American History. To learn more, click here for our comprehensive guide to American History.

Would you like to learn the complete history of the Civil War? Click here for our podcast series Key Battles of the Civil War

Would you like to learn the complete history of the Civil War? Click here for our podcast series Key Battles of the Civil War

Cite This Article

"Lincoln’s Landslide Victory in the Election of 1864" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

July 27, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/lincolns-landslide-victory-in-election-of-1864>

More Citation Information.