The Iranian Revolution of 1979 is an even that is poorly understood in the West. That is because it is a complex mixture of twentieth-century Cold War politics, a modern strain of political Islam, and both these elements mixed with a Persian culture thousands of years old that predates the great monotheistic religions.

This article will look at the origins of Persian culture, the events that led to the Iranian revolution, and the fall-out that still affects international politics in the twenty-first century.

The Persian Empire

The one thing anyone who believes in the historical account of the Old Testament knows about Iran is that the Persian Empire, created 2,500 years ago under Cyrus and Darius the Great, was an empire that largely had a positive effect on the ancient Near East. It allowed the exiled Jews to return home from Babylon and rebuild their temple in Jerusalem. In the seventh century, however, the Persian Empire collapsed, and the land that is now Iran became a Shiite Muslim domain—and it has remained thus for thirteen and a half centuries. Unlike Saudi Arabia, which did not exist until Abdulaziz ibn Saud crated it after World War I, Iran has been a coherent nation-state for more than five hundred years.

The Persians suffered under Mongol onslaught, but under the Safavid dynasty from 1501 to 1736,it was ruled by emperors known as shahs, Persia was one of the dozen or so empires that among them controlled nearly the entire human race. Under later dynasties after the Safavids, the Persians/Iranians were less formidable, but they maintained their independence proudly throughout. They were one of only a handful of nations in the Middle East and Asia to do so in the face of the global sweep of the great high-tech empires of the Western world.

Clash of empires: U.S. vs. Britain

Iran was a backwater through the nineteenth century. In 1908 its centuries of quietude ended with the discovery of significant reserves of oil Within four years, the dynamic and visionary young Winston Churchill, then first lord of the admiralty, had set up the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company to secure and develop Iran’s oil reserves as a reliable strategic fuel reserve for his navy, then still the strongest in the world. Anglo-Iranian Oil is still around today, having changed its name to British Petroleum (and now simply BP). And Churchill’s bold move, done to secure the oil to power the turbine engines of Britain’s revolutionary Queen Elizabeth–class battleships, became one of the handful of government initiatives that ever turned a fat profit for the taxpayer. For the next forty years, the British taxpayer and Anglo-Iranian’s shareholders made tremendous money from their Iranian operations. Iran retained its political independence and the British pretty much ignored domestic developments as long as they could develop and extract the oil.

World War II bolstered Iran’s importance because the country provided a safe and secure land bridge to ferry Lend/Lease supplies from Britain and America to the Soviet Union to help keep it in the war against Nazi Germany. When the shah at the time, Reza Shah, a peasant turned soldier turned general who had seized the throne in 1921, showed pro-Nazi sympathies, he was quickly and efficiently forced into exile. His son, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, was established as a harmless figurehead. So peaceful was Iran that the Allies chose its capital, Tehran, for the first Big Three summit in 1943 between U.S. president Franklin Roosevelt, British prime minister Churchill, and Soviet dictator Josef Stalin.

Until the early 1950s, Iranians knew little about the United States and cared less, and Americans felt the same way about them. That changed during the fateful presidency of Dwight D. Eisenhower. Mohammed Mosaddeq, a contemporary of Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser—and like him a romantic, idealistic, left-wing, anti- Western demagogue—took power in Iran in 1951 and nationalized the British oil industry there. The British (Churchill, ironically, was prime minister again) were furious, but having just liquidated their Indian empire and been forced out of their Palestine Mandate, they were in no position to do anything about it. Fearing an anti-American Iran, Eisenhower gave the CIA the green light to organize a military coup to topple Mosaddeq and give effective power back to Pahlavi, whom the British had installed back during World War II. It worked liked a charm.

But then the Western allies fell out. Iran’s oil was worth big bucks, rivaling Iraq as the holder of the second-largest reserves of the stuff. The oil was also easily accessible and of high quality. Eisenhower made sure the U.S. oil majors got favored access to it. The British were forced out of the primary position they had enjoyed in Iran for more than forty years, and Churchill, who had made it all possible, was forced to swallow the deal. The British were furious, but there was nothing they could do about it. From Washington’s point of view it all seemed hunky-dory. But Eisenhower had planted the seeds for future destruction.

The Iranian Revolution

Eisenhower then pushed ahead and got the young shah to approve Iran’s participation with Iraq, Turkey, and Pakistan in the Central Treaty Organization (CENTO), intended to be a Middle Eastern and South Asian extension of NATO (i.e., a tool for blocking the Soviet Union from expanding to the south into the Middle East and its oil fields).

Although Shah Pahlavi remained pro-Western (he had a taste for beautiful Western woman, Western nightlife, and parties on the Riviera), his people did not. The hatred and paranoia they had felt toward Britain for forty years was then shifted toward the United States for toppling Mosaddeq. That might not have mattered in the long term if the shah had left well enough alone and simply allowed free market economics and his bulging oil revenues to naturally raise living standards, or if he took care to respect his people’s traditional ways, as the far wiser rulers of Saudi Arabia and Kuwait were doing across the Gulf. But he didn’t.

For the shah had been infected by other Western passions. He was a liberal, social-reforming do-gooder. He imbibed the dominant political fashion of the time in Britain and America for socialism, big government, national planning, and social engineering. He called it his White Revolution. Millions of Iranians were uprooted from the land and forced into the towns and cities. While their standard of living rose, they missed their old, slow-moving, cherished way of life.

American liberals, especially in the media, loved it, and the shah was played up as a mixture of Winston Churchill, Franklin Roosevelt, and Mother Teresa. He was launching his own New Deal and curing the backward folk of their repressive traditions and religion. Time magazine was a particularly enthusiastic and witless booster. Only the Iranian people disagreed.

The shah’s dependence on the United States and his honeymoon with Israel in the 1950s and 1960s deluded leaders in both countries that Iran was inherently moderate, anti-Arab, and pro-Western. They couldn’t have been more wrong. Anti-American and anti- Israeli popular sentiment grew dramatically in Iran during those years.

Meanwhile, U.S. state-of-the-art aircraft, tanks, and automatic weapons flowed to the shah in an unending stream, with President Nixon’s blessing. But within two years, the shah had turned upon and bitten the hand that fed him. He joined forces with Saudi Arabia, his nation’s historic rival and enemy on the other side of the Gulf, and supported King Faisal in implementing an unprecedented quadrupling of the global price of oil in the winter of 1973–1974 through the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). The U.S. domestic economy dropped as if pole-axed. Faisal and the shah overnight caused more damage to the United States than the Soviet Union, Communist China, and the Korean and Vietnam wars combined.

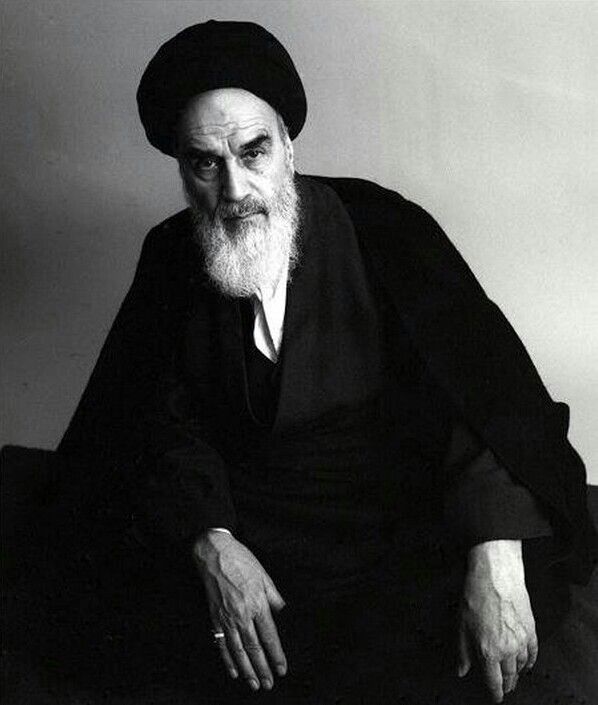

Amazingly, future presidents would mess up the Iran situation even more. In an eerie foreshadowing of disastrous U.S. policies of the early twenty-first century, Democratic president Jimmy Carter was so obsessed with fostering democracy and human rights in Iran that he fatally undermined and distracted the shah. Like so many other big-government, reform-minded liberals before him, Pahlavi did not realize that by destroying the old traditions of society, he was also destroying the foundation his own regime rested on. The most conservative, backward (in the very best sense of the word), and peaceful society in the Middle East was transformed and modernized, pitched into restless motion. Iran was cut off from its own stable past, longing for it and yet ripe for radical change. Enter Grand Ayatollah Ruhullah Khomeini, the Man in Black.

Ayatollah Khomeini: The fruit of American meddling

In 1977–1978, popular pressures on the shah and protests against him steadily grew. President Carter was insistent that the shah divest himself of much of his power and start to democratize Iran. At the very least, he had to rein in his own elite special forces and his secret police. Meanwhile, Iran was transformed by a sudden wave of extreme Shiite Islamists, stirred up by the endless recorded sermons of an eminent but hitherto obscure cleric, one Ayatollah Ruhullah Khomeini, already in his late seventies and living in exile in Paris. Khomeini was backed by Iranian extreme leftists supported by motley sources ranging from the Soviet KGB to the Palestine Liberation Organization—all of them bitter enemies of the United States. Yet all Carter seemed to care about was lecturing the shah to improve his human rights record.

The U.S. government certainly didn’t want the shah to fall, and if he did, senior U.S. policymakers hoped that a stable, democratic, pro- American coalition could be shepherded to power in his place. This fantasy was a striking contrast to what a more confident, competent CIA serving a vastly more competent president—Dwight Eisenhower—had managed to pull off in toppling the democratically elected Mohammed Mosaddeq to restore the shah to full power a quarter-century before. It was also remarkably similar to the fantasies that U.S. policymakers on the National Security Council and within the Pentagon harbored for their fantasy of a democratic and pro-American Iraq a quarter-century later.

Carter bumbled, micromanaged, ignored, pettifogged, and lectured the shah—and then he lost Iran. The shah fell and was forced to flee in January 1979. There was chaos on the streets. Khomeini came home to be greeted as the nation’s greatest hero. A beaming Yasser Arafat flew in from southern Lebanon. Khomeini almost never smiled, but he was all grins and hugs for the Palestinian revolutionary leader. America’s humiliation was only just beginning. While all this was going on, incredibly, Carter delivered far more effort to brokering a final peace treaty between Israel and Egypt (which were already in a state of de facto peace, and both countries were already in the U.S. orbit).

Carter’s standing in the opinion polls steadily declined. It didn’t help that the dragon of inflation, briefly defeated by President Gerald Ford, was rising again. And in that same fateful year of 1979 the OPEC nations pushed through another massive oil price hike with newly radicalized Iran eagerly supporting it. As it had done six years before, the U.S. economy reeled.

Carter and the hostage crisis

On top of all that, Iranian “students” (they were actually revolutionary paramilitary forces acting with the full support of their government) stormed the U.S. embassy in Tehran and held fifty-two diplomats and other American citizens hostage. For 444 days these Americans were prisoners, regularly tortured and abused. Carter couldn’t get them out.

At one point, he approved a plan for U.S. Special Forces to launch a commando raid in the heart of Tehran to free them. It was an exceptionally daring, dangerous, and risky concept to start with. U.S. troops were being sent into the heart of a capital city of eight million people, almost all of whom hated them. We had never tried this sort of thing before.

To make things even worse, Carter micromanaged again. At the last minute, he slashed the number of helicopters for the mission. For twenty years, the focus of U.S. military operations had been in the damp rain forests of Southeast Asia. American forces had done no serious desert fighting since the Italian and Nazi forces had surrendered to Eisenhower, Patton, and Bradley in Tunisia thirty-six years before. So the sand of the desert that jammed key helicopter mechanisms and caused one of them to crash came as a surprise. The mission was aborted. Details of it were soon discovered and revealed to the world. The U.S. national humiliation was complete.

To add to Carter’s woes, and to underscore the complete contempt that Kremlin policymakers now had for him, in December 1979 Soviet president Leonid Brezhnev approved the invasion and effective takeover of Afghanistan. In less than nine months, the shining achievement of Camp David (as it seemed at the time) had been entirely overshadowed. The U.S. and Western position in the Middle East seemed to be crumbling by the hour.

After the Iranian Revolution

The history of the Islamic Republic in the twenty-nine years since Ayatollah Khomeini seized power fits into four general periods:

1. The era of war and confrontation

2. The era of isolation

3. The era of (relative) moderation

4. The era of renewed belligerence

Khomeini was eager for war and confrontation. Like so many fanatical revolutionaries before him, from Robespierre in the French Revolution to Lenin in the Bolshevik Revolution, Khomeini was convinced that the perfection of his revolutionary ideas and teachings would sweep up millions of people in an irresistible tide. And like Robespierre and Lenin, he was wrong. For Khomeini, Carter’s folly was an ecstatic victory over the United States; nothing like it had been seen since Nasser’s day nearly a quartercentury before. But the tide was about to change, thanks to America’s secret weapon in the Middle East. His name was Saddam Hussein.

In September 1980, Saddam invaded Khuzestan, an oil-rich coastal province of Iran. He thought the Iranian Revolution was tottering and that the Iranians would fall apart. It was the same mistake Adolf Hitler had made when he invaded the Soviet Union and set off a war to the death with Saddam’s personal hero Josef Stalin. What happened next should give any Americans and Israelis enthusiastic about invading Iran pause. The Iranian people rallied behind Khomeini, and as Iran’s population was more than four times Iraq’s, after a few months the tide turned and the Iraqis were forced back into their country.

Saddam sensibly sought peace, but Khomeini was implacable when aroused. He was determined to crush the Iraqi state and then sweep on across the Middle East. Heedless of the cost to his own people, he pushed forward. Teenage boys, including many as young as twelve, were recruited into fanatical suicide attack squads. Between half a million and a million Iranians were killed in the war, and possibly as many as 100,000 Iraqis died. As long as Khomeini lived, any armistice or compromise was out of the question and the suicide attacks and massacre of innocents continued. The Iraqis showed no hesitation in using poison gas—almost unknown in warfare since World War I—against the Iranians and killed perhaps 100,000 Iranian soldiers with it. Finally, in 1988, even Khomeini was forced to recognize the inevitable and accept a compromise cease-fire. The act of peace-making probably proved too much for him; he died the following year at the ripe old age of eighty-six.

Moderation After the Iranian Revolution

For the next eight years, Iran remained very much in the international doghouse. Khomeini’s nemesis, Saddam, emboldened by what he imagined was success—though it had cost his country scores of billions of dollars and at least 100,000 lives—followed the war by invading Kuwait only two years later and bringing the wrath of the United States on his head.

Saddam’s humiliation and the virtual destruction of his great army, the fourth largest in the world at the time, in the 1991 Gulf War was welcome news to the ayatollahs ruling in Tehran. But now the United States was stronger in the region than ever, especially following the collapse of the Soviet Union at the end of 1991. The Iranians remained isolated until 1997, when a relative moderate, President Mohammad Khatami, was elected as president of the Islamic Republic.

Khatami’s two terms of leadership from 1997 to 2005 marked the third era of the history of the Islamic Republic. The United States remained the invincible superpower, and Saddam, though humbled, continued to rule in Baghdad amid many media reports of his renewed programs to develop powerful weapons of mass destruction. Iranians—both in the leadership and general population—were still terrified of the ogre who had inflicted so much suffering on them, so Iranian leaders continued to tread carefully between Baghdad and Washington. They gingerly improved their diplomatic and trade ties with the nations of Asia and Western Europe. China and India both had growing demands for their oil.

And Khatami even sought to mend his country’s long-destroyed ties with the United States. He offered to both the Clinton and Bush administrations to scrap Iran’s nuclear program in return for a guarantee that the United States would recognize the Islamic Republic and respect its sovereignty. With the benefit of hindsight, the deal could have worked. It would have been subject to verification. President George W. Bush would eventually agree to a far more limited and problematic agreement with North Korea on restricting its nuclear development.

Such a deal would have been of crucial benefit to Israel. In the first decade of the twenty-first century, it became clear that the Iranian nuclear program posed probably the gravest threat to the existence of the Jewish state since its creation. But ironically, pro-Israel activists in Washington were the loudest in urging its rejection. Khatami had humbled his country and begged for peace, but was sent away from the table.

Democracy’s bitter gift: Mahmoud Ahmadinejad

Unable to deliver improved ties with the United States, Iranian voters took a new direction in 2005, electing a president fond of a mock turtleneck and blazer. Mahmoud Ahmadinejad brought in the fourth era of the Islamic Republic: renewed belligerence and confrontation with the United States and Israel. During Khatami’s eight years as president of Iran, the usual babbling pundits and armchair strategists in the United States endlessly asserted that it did not matter who was chief executive of Iran and that all Iranian leaders were really identical hard-line arch-villains who should never be mollified.

But when Ahmadinejad replaced Khatami, it soon became clear that who the leader was mattered a great deal. Ahmadinejad was open in his determination to develop nuclear weapons and ready to defy the whole world if necessary. He sought to delegitimize Israel’s existence and boasted about obliterating it in language not heard since the heydays of Nasser and Saddam. He purged the Iranian government of relative moderates and put his hard-line allies into every key national security and military post he could. He also made no secret of his passionate loyalty to the vanished Twelfth Imam of Shiite Islam, and even ordered minutes of every Iranian cabinet meeting to be dropped down the well where the Twelfth Imam was said to have vanished.

Ahmadinejad was able to get away with this outrageous behavior because one enormous miscalculation had reversed twenty-four years of continual military defeat, massive casualties, diplomatic isolation, and strategic fear: the United States had invaded Iraq and toppled Saddam Hussein in 2003. By doing so, the Bush administration removed both enemies the ayatollahs most feared at a single stroke—Saddam and the United States itself.

For in the years following the toppling of Saddam, the 130,000 to 160,000 U.S. troops in Iraq were tied down, suffering slow but steady casualties from Sunni Muslim insurgents. Following the implementation of new strategies by General David Petraeus in 2007, which sought to cooperate with existing local Sunni leaderships in Anbar Province, the Sunni insurgency at last began to run out of steam. But by then, all of southern Iraq was run by local Shiite militias sympathetic to and backed by Iran, and the Shiite-dominated government of Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki in Baghdad was seeking warm ties with Tehran as well.

Far from being a threat to Iran by being based in a strong ally next door, the U.S. ground forces in Iraq, with their communications lines to Kuwait and the Gulf running through Shiite militia–controlled territory, were increasingly at the mercy of Shiite groups sympathetic to Iran. No wonder Ahmadinejad was so bold and confident. The U.S. invasion and occupation of Iraq therefore reversed a highly successful process of attrition, exhaustion, and containment that had handicapped the Iranian Revolution for the previous twenty-four years. Neo-Wilsonian liberal nation-building had failed yet again.

Iran on borrowed time

But by 2008 there was another factor driving the Iranians to more hardline policies: the Islamic Republic was running out of oil—and therefore out of time. Iran’s oil fields had been developed earlier and more vigorously than those of any Gulf nation. They were energetically pumping oil for the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company and Britain’s Royal Navy for twenty years before Ibn Saud even signed his epochal agreement with Standard Oil of California to authorize the prospecting that led to the discovery of Saudi Arabia’s great Dhahran oil fields. By the early years of the twenty-first century, the Iranians were already importing natural gas to pump pressure into their depleted fields. Far from threatening to become a swing producer, it was clear that after a few more years of peak production, Iran would be lucky to be a dangling producer, holding onto its market share in OPEC by the skin of its teeth.

If Iran’s oil reserves had been discovered and developed in the 1930s, like Saudi Arabia’s, then today the Islamic Republic would still be sitting pretty, enjoying enormous financial and mineral resources for decades to come, but Winston Churchill’s energy and vision in getting the oil pumping by World War I meant that by 2008 the ayatollahs were living on borrowed time. That meant they had to push for maximum global prices in the OPEC cartel to get the maximum profits they could from their remaining oil. And it meant they had a far more pressing motive to try to seize the still enormous oil reserves of Iraq and Saudi Arabia for themselves by exporting the Iranian Revolution to them if they got the chance. Nearly a century after he made the deal, Churchill’s epochal Anglo-Iranian oil venture was still driving destiny in the Middle East.

This article is part of our larger selection of posts about American History. To learn more, click here for our comprehensive guide to American History.

Cite This Article

"The Iranian Revolution: Persia Before, During, and After 1979" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

July 25, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/middle-east-the-iranian-revolution>

More Citation Information.