The following article on the fall of the Soviet Union is an excerpt from Lee Edwards and Elizabeth Edwards Spalding’s book A Brief History of the Cold War It is available to order now at Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

The fall of the Soviet Union was a decades-in-the-making outcome of Cold War politics, but it happened quite suddenly in the late 80s and early 90s, primarily at the level of U.S.-USSR politics. Even then the end was not clear. The first of the three Bush-Gorbachev summit meetings did not take place until December 1989 in Malta, where Bush emphasized the need for “superpower cooperation,” choosing to overlook that the Soviet Union was no longer a superpower by any reasonable criterion and that Marxism-Leninism in Eastern Europe was headed for Reagan’s “ash-heap of history.”

The second summit was in May 1990 in Washington, D.C., where the emphasis was on economics. Gorbachev arrived in a somber mood, conscious that his country’s economy was nearing free fall and nationalist pressures were splitting the Soviet Union. Although a virtual pariah at home, the Soviet leader was greeted by large, friendly American crowds. Bush tried to help, granting most-favored-nation trading status to the Soviet Union. Gorbachev appealed to American businessmen to start new enterprises in the USSR, but what could Soviet citizens afford to buy? In Moscow the bread lines stretched around the block. A month later, NATO issued a sweeping statement called the London Declaration, proclaiming that the Cold War was over and that Europe had entered a “new, promising era.” But the Soviet Union, although teetering, still stood.

The Fall of the Soviet Union Accelerates

The shrinking Soviet Union received another major blow when the biggest republic, Russia, elected its own president, Boris Yeltsin. A former Politburo member turned militant anticommunist, Yeltsin announced his intention to abolish the Communist Party, dismantle the Soviet Union, and declare Russia to be “an independent democratic capitalist state.”

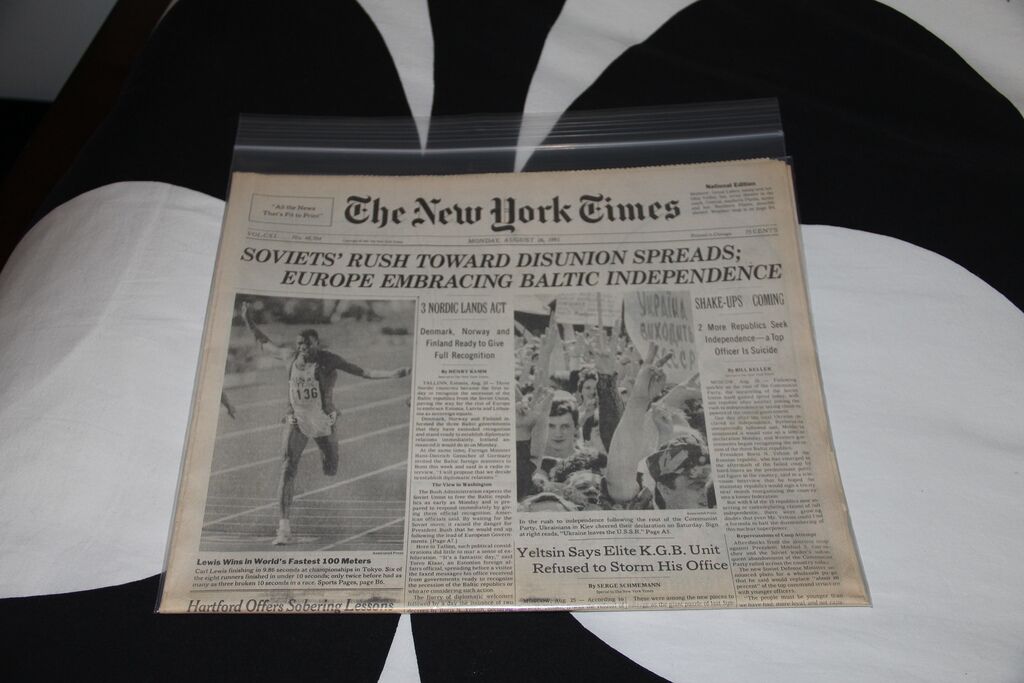

For the remaining Stalinists in the Politburo, this was the final unacceptable act. Barely three weeks after the Bush-Gorbachev summit in Moscow, the head of the KGB, the Soviet defense and interior ministers, and other hard-liners—the so-called “Gang of Eight”—launched a coup. They placed Gorbachev under house arrest while he was vacationing in the Crimea, proclaiming a state of emergency and themselves the new leaders of the Soviet Union. They called in tanks and troops from outlying areas and ordered them to surround the Russian Parliament, where Yeltsin had his office.

Some eight decades earlier, Lenin had stood on a tank to announce the coming of Soviet communism. Now Yeltsin proclaimed its end by climbing onto a tank outside the Parliament and declaring that the coup was “unconstitutional.” He urged all Russians to follow the law of the legitimate government of Russia. Within minutes, the Russian defense minister stated that “not a hand will be raised against the people or the duly elected president of Russia.” A Russian officer responded, “We are not going to shoot the president of Russia.”

The image of Yeltsin boldly confronting the Gang of Eight was flashed around the world by the Western television networks, especially America’s CNN, none of whose telecasts were blocked by the coup plotters. The pictures convinced President Bush (on vacation in Maine) and other Western leaders to condemn the coup and praise Yeltsin and other resistance leaders.

The attempted coup, dubbed the “vodka putsch” because of the inebriated behavior of a coup leader at a televised news conference, collapsed after three short days. When Gorbachev returned to Moscow, he found that Boris Yeltsin was in charge. Most of the organs of power of the Soviet Union had effectively ceased to exist or had been transferred to the Russian government. Gorbachev tried to act as if nothing had changed, announcing, for example, that there was a need to “renew” the Communist Party. He was ignored. The people clearly wanted an end to the party and him. He was the first Soviet leader to be derided at the annual May Day parade, when protestors atop Lenin’s tomb in Red Square displayed banners reading, “Down with Gorbachev! Down with Socialism and the fascist Red Empire. Down with Lenin’s party.”

A supremely confident Yeltsin banned the Communist Party and transferred all Soviet agencies to the control of the Russian republic. The Soviet republics of Ukraine and Georgia declared their independence. As the historian William H. Chafe writes, the Soviet Union itself had fallen “victim to the same forces of nationalism, democracy, and anti-authoritarianism that had engulfed the rest of the Soviet empire.”

President Bush at last accepted the inevitable—the unraveling of the Soviet Union. At a cabinet meeting on September 4, he announced that the Soviets and all the republics would and should define their own future “and that we ought to resist the temptation to react to or comment on each development.” Clearly, he said, “the momentum [is] toward greater freedom.” The last thing the United States should do, he said, is to make some statement or demand that would “galvanize opposition . . . among the Soviet hard-liners.” However, opposition to the new non-communist Russia was thin or scattered; most of the hard-liners were either in jail or exile.

On December 12, Secretary of State James Baker, borrowing liberally from the rhetoric of President Reagan, delivered an address titled “America and the Collapse of the Soviet Empire.” “The state that Lenin founded and Stalin built,” Baker said, “held within itself the seeds of its demise. . . . As a consequence of Soviet collapse, we live in a new world. We must take advantage of this new Russian Revolution.” While Baker praised Gorbachev for helping to make the transformation possible, he made it clear that the United States believed his time had passed. President Bush quickly sought to make Yeltsin an ally, beginning with the coalition he formed to conduct the Gulf War.

Gorbachev’s Role in the Fall of the Soviet Union

A despondent Gorbachev, not quite sure why it had all happened so quickly, officially resigned as president of the Soviet Union on Christmas Day 1991—seventy-four years after the Bolshevik Revolution. Casting about for reasons, he spoke of a “totalitarian system” that prevented the Soviet Union from becoming “a prosperous and well-to-do country,” without acknowledging the role of Lenin, Stalin, and other communist dictators in creating and sustaining that totalitarian system. He referred to “the mad militarization” that had crippled “our economy, public attitudes and morals” but accepted no blame for himself or the generals who had spent up to 40 percent of the Soviet budget on the military. He said that “an end has been put to the cold war” but admitted no role for any Western leader in ending the war.

After just six years, the unelected president of a nonexistent country stepped down, still in denial. That night, the hammer and sickle came down from atop the Kremlin, replaced by the blue, white, and red flag of Russia. It is an irony of history, notes Adam Ulam, that “the claim of Communism being a force for peace among nations should finally be laid to rest in its birthplace.” Looking back at America’s longest war and the fall of the Soviet Union, Martin Malia writes, “The Cold War did not end because the contestants reached an agreement; it ended because the Soviet Union disappeared.”

When Gorbachev reached for the pen to sign the document officially terminating the USSR, he discovered it had no ink. He had to borrow a pen from the CNN television crew covering the event. It was a fitting end for someone who was never a leader like Harry Truman or Ronald Reagan, who had clear goals and the strategies to reach them. Gorbachev’s attempt to do too much too quickly, the historians Edward Judge and John Langdon conclude, “coupled with his underestimation of the potency of the appeal of nationalism, split the Communist party and wrecked the Soviet Union.”

Gorbachev experimented, wavered, and at last wearily accepted the dissolution of one of the bloodiest regimes in history. He deserves credit (if not the Nobel Peace Prize) for recognizing that brute force would not save socialism in the Soviet Union or its satellites or prevent the fall of the Soviet Union.

This article is part of our larger selection of posts about the Cold War. To learn more, click here for our comprehensive guide to the Cold War.

This article on the fall of the Soviet Union is an excerpt from Lee Edwards and Elizabeth Edwards Spalding’s book A Brief History of the Cold War. It is available to order now at Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

You can also buy the book by clicking on the buttons to the left.

Cite This Article

"Fall of the Soviet Union: The Cold War Ends" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

July 25, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/fall-of-the-soviet-union>

More Citation Information.