Robert E Lee’s Gettysburg Campaign ended in the Union claiming victory after three days of battle with Lee’s army. Both parties suffered major losses of life.

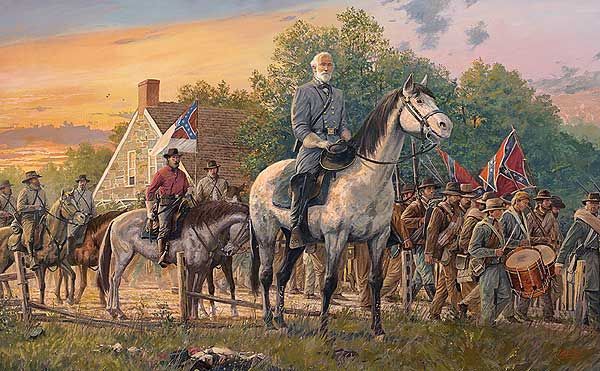

Robert E Lee Gettysburg Campaign

With Ewell engaged, Lee changed his mind and decided to attack the center of the Union line. The evening before, Union Major General John Newton, Reynolds’s replacement as commander of the First Corps, had told Meade that he should be concerned about a flanking movement by Lee, who would not be “fool enough” to frontally attack the Union army in the strong position into which the first two days’ fighting had consolidated it. Around midnight Meade told Brigadier General John Gibbon that if Lee went on the offensive the next day, he would attack Gibbon’s Second Division of the Second Corps in the center of the Union line. Gibbon replied that if Lee did so, he would be defeated.

Lee, however, saw things differently. Again ignoring the advice and pleas of Longstreet, Lee canceled Longstreet’s early morning orders for a flank attack and instead ordered the suicidal assault known as Pickett’s Charge.144 After studying the ground over which the attack would occur, Longstreet said to Lee, “The 15,000 men who could make a successful assault over that field had never been arrayed for battle.” Longstreet was not alone in his bleak assessment of the chances for success. Brigadier General Ambrose “Rans” Wright said there would be no difficulty reaching Cemetery Ridge but that staying there was another matter because the “whole Yankee army is there in a bunch.” On the morning of the third, Brigadier General Cadmus Wilcox told his fellow brigadier Richard Garnett that the Union position was twice as strong as Gaines’s Mill at the Seven Days’ Battles.

Edward Porter Alexander shared the complete, almost blind, faith of the Confederate troops in Lee, later remarking, “ . . . like all the rest of the army I believed that it would come out right, because Gen. Lee had planned it.” But historian Bevin Alexander has severely criticized Lee’s order: “When his direct efforts to knock aside the Union forces failed, Lee compounded his error by destroying the last offensive power of the Army of Northern Virginia in Pickett’s charge across nearly a mile of open, bullet-and-shell-torn ground. This frontal assault was doomed before it started.”

The famous attack was preceded by a massive artillery exchange—so violent and loud that it was heard 140 miles away. Just after one o’clock, Alexander unleashed his 170 rebel cannon against the Union forces on Cemetery Ridge. Two hundred Federal cannon responded. Across a mile of slightly rolling fields, the opposing cannons blasted away for ninety minutes. The Confederate goal was to soften up the Union line, particularly to weaken its defensive artillery capacity, prior to a massive assault on the center of that line. Some Federal batteries were hit, as were horses and caissons on the reverse slope near Meade’s headquarters.

Alexander’s cannonade continued until his supply of ammunition was dangerously low. A slowdown in the Union artillery response gave a false impression that the Confederate cannonade had inflicted serious damage. Although Alexander received some artillery assistance from Hill’s guns to the north, Ewell’s five artillery battalions northeast of the main Confederate line fired almost no rounds. Artillery fire was one thing that Ewell could have provided, but the commanding general and his chief of artillery also failed to coordinate this facet of the offensive.

The time of decision and death was at hand for many of the fifty-five thousand Confederates and seventy-five thousand Yankees. The rebels were about to assault a position that Alexander described as “almost as badly chosen as it was possible to be.” His rationale:

Briefly described, the point we attacked is upon the long shank of the fishhook of the enemy’s position, & our advance was exposed to the fire of the whole length of that shank some two miles. Not only that, that shank is not perfectly straight, but it bends forward at the Round Top end, so that rifled guns there, in secure position, could & did enfilade the assaulting lines. Now add that the advance must be over 1,400 yards of open ground, none of it sheltered from fire, & very little from view, & without a single position for artillery where a battery could get its horses & caissons undercover.

I think any military engineer would, instead, select to attack the bend of the fishhook just west of Gettysburg.

There, at least, the assaulting lines cannot be enfiladed, and, on the other hand, the places selected for assault may be enfiladed, & upon shorter ranges than any other parts of the Federal lines. Again there the assaulting column will only be exposed to the fire of the front less than half, even if over one fourth, of the firing front upon the shank.

Around 2:30, Alexander ordered a cease-fire and sent a hurried note to General Longstreet: “If you are coming at all, you must come at once or I cannot give you proper support, but the enemy’s fire has not slackened at all. At least 18 guns are still firing from the cemetery itself.” Longstreet, convinced of the impending disaster, could not bring himself to give a verbal attack order to Major General George E. Pickett. Instead, he merely nodded his permission to proceed after Pickett asked him, “General, shall I advance?”

On the hidden western slopes of Seminary Ridge, nine brigades of thirteen thousand men began forming two mile-and-a-half-long lines for the assault on Cemetery Ridge. Their three division commanders were Pickett, Major General Isaac Trimble (in place of the wounded Dorsey Pender), and Brigadier General J. Johnston Pettigrew (in place of the wounded Henry Heth). Pickett gave the order, “Up men, and to your posts! Don’t forget today that you are from old Virginia!” With that, they moved out.

After sending his “come at once” message, Alexander noticed a distinct pause in the firing from the cemetery and then clearly observed the withdrawal of artillery from that planned point of attack. Ten minutes after his earlier message and while Longstreet was silently assenting to the attack, Alexander sent another urgent note: “For God’s sake come quick. The 18 guns are gone. Come quick or I can’t support you.” To Alexander’s chagrin, however, the Union chief of artillery, Henry J. Hunt, moved five replacement batteries into the crucial center of the line. What Alexander did not yet know was that the Union firing had virtually ceased in order to save ammunition to repel the coming attack and to bring up fresh guns from the artillery reserve. Hunt had seventy-seven short-range guns in the position the rebels intended to attack, as well as numerous other guns, including long-range rifled artillery, along the line capable of raking an attacking army.

The rebel lines opened ranks to pass their now-quiet batteries and swept on into the shallow valley between the two famous ridges. A gasp arose from Cemetery Ridge as the two long gray lines, a hundred fifty yards apart, came into sight. It was three o’clock, the hottest time of a scorching day, and forty thousand Union soldiers were in position directly to contest the hopeless Confederate assault. Many defenders were sheltered by stone walls or wooden fences. Their awe at the impressive parade coming their way must have been mixed with an understandable fear of battle and confidence in the strength of their numbers and position.

As the charging rebels approached the stronghold on Cemetery Ridge, their fear grew and their confidence waned with every step. The forty-seven regiments (including nineteen from Virginia and fourteen from North Carolina) initially traversed the undulating landscape in absolute silence except for the clunking of their wooden canteens. Although a couple of swales provided temporary shelter from most of the Union rifle fire, the Confederates were under constant observation from Little Round Top to the southeast. Long-range artillery fire began tearing holes in the Confederate lines. The attackers turned slightly left to cross the Emmitsburg Pike and found themselves in the middle of a Union semi-circle of rifles and cannon. They attempted to maintain their perfect parade order, but all hell broke loose when short-range round shot from Federal cannon exploded along the entire ridgeline—from Cemetery Hill on the north to Little Round Top on the south.

Minié balls and double loads of canister (pieces of iron) decimated the Confederate front ranks. The slaughter was indescribably horrible, but the courageous rebels closed ranks and marched on. Taking tremendous losses, they started up the final rise toward the copse that was their goal, all the while viciously assaulted from the front, from both flanks, and even from their rear. The rifle fire from Brigadier General George J. Stannard’s advanced Vermont brigade, shot point-blank into the rebel right flank, was especially devastating. Soon the numbers of the attackers dwindled to insignificance. The survivors let loose their rebel yell and charged the trees near the center of Cemetery Ridge. With cries of “Fredericksburg,” the men in blue cut down the remaining attackers with canister and Minié balls. General Lewis Armistead led 150 men in the final surge across the low stone wall, where he fell mortally wounded. The rest were killed, wounded, or captured within minutes.

Seventeen hundred yards away, Lee watched his gray and butternut troops disappear into the all-engulfing smoke on the ridge and then saw some of them emerge in retreat. Fewer than seven thousand of the original thirteen thousand returned to Seminary Ridge. There was no covering fire from Alexander’s cannon because he was saving his precious ammunition to repel the expected counterattack. As the survivors returned to Confederate lines, Lee met them and sobbed, “It’s all my fault this time.” It was.

Lee and Longstreet tried to console Pickett, who was distraught over the slaughter of his men. Lee told him that their gallantry had earned them a place in history, but Pickett responded: “All the glory in the world could never atone for the widows and orphans this day has made.” To his death, Pickett blamed Lee for the “massacre” of his division.

The result of Lee’s Day Three strategy was the worst single-charge slaughter of the whole bloody war, with the possible exception of John Bell Hood’s suicidal charge at Franklin, Tennessee, the following year. The Confederates suffered 7,500 casualties to the Union’s 1,500. More than a thousand of those rebel casualties were killed—all in a thirty-minute bloodbath. Brigadier General Richard Garnett, whose five Virginia regiments led the assault, was killed, and 950 of his 1,450 men were killed or wounded. Three regiments—the Thirteenth and Forty-Seventh North Carolina and the Eighteenth Virginia—were virtually wiped out on Cemetery Ridge.

That night Lee rode alone among his troops. At one point he met Brigadier General John D. Imboden, who remarked, “General, this has been a hard day on you.” Lee responded, “Yes, it has been a sad, sad day to us.” He went on to praise Pettigrew’s and Pickett’s men and then made this puzzling statement: “If they had been supported as they were to have been—but for some reason not fully explained to me were not—we would have held the position and the day would have been ours. Too bad. Too bad. Oh, too bad.” General Alexander found that comment inexplicable since Lee was the commanding general and had personally overseen the entire preparation for and execution of the disastrous charge.

Even if Lee was nonplussed, his officers had little difficulty seeing the folly of Pickett’s Charge and its similarity to the senseless Union charges at Fredericksburg the previous December. Having lost over half his own 10,500 men in the July 3 charge, Pickett submitted a battle report highly critical of that assault—and probably of the commander who ordered it. Lee declined to accept the report and ordered it rewritten. It never was.

The only saving grace for Lee’s battered army was that General Meade, believing his mission was to not lose rather than to win, failed to follow up his victory with an immediate infantry counterattack on the stunned and disorganized Confederates. To Lincoln’s chagrin, Meade developed a case of the “slows” reminiscent of McClellan after Antietam and took nine days to pursue and catch Lee, who was burdened by a seventeen-mile ambulance train. Unlike McClellan’s army at Antietam, however, Meade’s entire army had been engaged and battered in the fight at Gettysburg. After missing his chance for a quick and decisive strike, Meade wisely did not attack Lee’s strongly entrenched position at Williamsport, Maryland, on the Potomac River after Meade had caught up with him. As the Confederates waited to cross, Confederate officers hoped for a Union assault: “Now we have Meade where we want him. If he attacks us here, we will pay him back for Gettysburg. But the Old Fox is too cunning.” Alexander recalled, “ . . . oh! how we all did wish that the enemy would come out in the open & attack us, as we had done them at Gettysburg. But they had had their lesson, in that sort of game, at Fredbg. [Fredericksburg] & did not care for another.” Lee’s army crossed the receding river and returned ignominiously to Virginia.

This article is part of our larger selection of posts about the Civil War. To learn more, click here for our comprehensive guide to the Civil War.

Would you like to learn the complete history of the Civil War? Click here for our podcast series Key Battles of the Civil War

Cite This Article

"Robert E. Lee & Gettysburg: How the Confederacy Lost" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

July 24, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/robert-e-lee-gettysburg-why-confederate-lost>

More Citation Information.