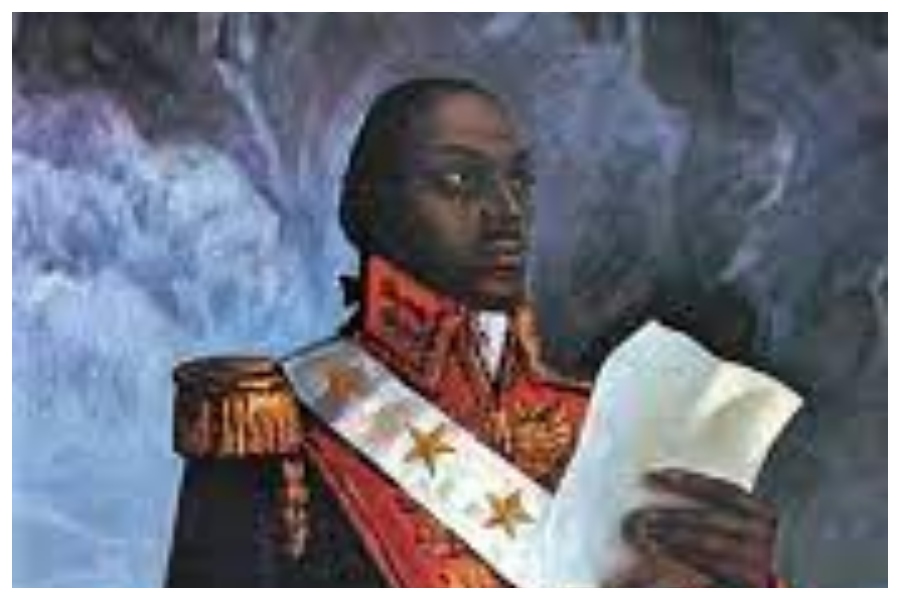

Toussaint Louverture was unquestionably one of the great unsung figures of American history, if only by proxy.

Whether his impact was noble or despotic would certainly be up for debate, but his impact and influence were indisputable.

Following the French invoking the recently constructed “Declaration Of The Rights Of Man”, there was Haitian class warfare that erupted between the black and mixed-race inhabitants of the island with the white planter class.

So it was in 1793 that Great Britain and Spain knocked on the door of the conflict. The British fought at the side of the white planter class and sought to restore order to the now chaotic and unprofitable colony. Meanwhile, the Spanish had control of Hispanola, which was on the other side of the island, and rather favored colonial disruption of the French.

This sets the stage for the advent of Toussaint Louverture and what would become known as the Haitian revolution.

Toussaint Louverture was born François Dominique Toussaint as a slave in what would become Haiti (then known as Saint Domingue) around 1743. The eldest of eight children, he was taught early how to read and write in both French and Haitian as well as having an impromptu education in medicine as taught by his father. By his 30s, he was free and had set his sights on becoming a property owner and working his way up the Haitian caste system.

It was in 1791, with the French revolution only barely in the rearview mirror of history that the uprising and revolt of the enslaved people of Saint-Domingue took on its own life as a serious revolution.

While being free himself, Toussaint saw an opportunity in the slave rebellion and happily took up arms against oppression and for liberation.

Toussaint showed himself to be a natural fighter and leader and was quickly promoted to general. It was in 1793, Toussaint added “Louverture” to his name, which is french for “opening” and was presumably attributed to his deftness at creating openings in enemy lines.

According to britannica.com, when France and Spain went to war in 1793, the Black commanders joined the Spaniards of Santo Domingo, the eastern two-thirds of Hispaniola (now the Dominican Republic). Knighted and recognized as a general, Toussaint demonstrated extraordinary military ability and attracted such renowned warriors as his nephew Moïse and two future monarchs of Haiti, Jean-Jacques Dessalines and Henry Christophe. Toussaint’s victories in the north, together with mulatto successes in the south and British occupation of the coasts, brought the French close to disaster. Yet, in May 1794, Toussaint went over to the French, giving as his reasons that the French National Convention had recently freed all slaves, while Spain and Britain refused, and that he had become a republican.

His switch was decisive: the governor of Saint-Domingue, Étienne Laveaux, made Toussaint lieutenant governor; the British suffered severe reverses, and the Spaniards were expelled.

So by 1795, Toussaint was rather famous and even loved. He did, however, exhibit the impulse of tyranny, even if it took a somewhat dulled form. He did force former slaves to work, but they were free and equal as far as the law was concerned and they got a share of the profits of the restored plantations.

From 1796 to 1797, Toussaint did a fairly masterful job at consolidating power for himself. A French commissioner names Leger-Felicite Sonthonax made Louverture governor-general. Sonthonax. Louverture rather despised Sonthonax’s terrorist agenda of European extermination, as well as his atheism. Toussaint did eventually force Sonthonax out in 1797.

Then in between 1798 and 1799, Toussaint set his sights on the British, which suffered heavy losses and wanted to negotiate with Toussaint, culminating in Britain’s withdrawal. So, he began trading with Britain and with the United States. In return for arms and goods, Toussaint sold sugar and promised not to invade Jamaica or the American South. Britain even offered to recognize Toussaint as king of an independent Haiti, but Toussaint, who was skeptical, to put it mildly of the British because they upheld slavery, refused.

Among this scramble for power was the salient event which came to be known as the War of Knives. In June 1799, Toussaint went up against Andre Rigaud, who himself ruled what could be described as a semi-independent state in the south.

It was a decisive victory for Toussaint, which saw exile for Rigaud and would grant for Toussaint, following formal recognition by the envoy of newly empowered Napoleon Bonaparte, the position as general-in-chief and by late 1800, Toussaint held absolute power over Saint Domingue.

Toussaint would prove to be trouble for Bonaparte, who saw Toussaint as a roadblock to full restoration of Saint Domingue as a profitable colony.

Toussaint understood that Bonaparte wanted to reinstitute slavery and was also aware that Bonaparte would seek to intimidate the island upon making peace with England; therefore, he drilled a huge army and stored supplies.

With this less than friendly relationship fermented, a french invasion began in 1802, with General Charles Leclerc at the helm. The invasion would prove successful after a large number of defectors joined Leclerc. So in May of that year, Toussaint conditionally surrendered to Bonaparte with the proviso that Leclerc promise to not restore slavery.

Following retirement to a plantation, French general Jean-Baptiste Brunet, in June, invited Toussaint to a parley under false pretenses. Under orders from Napoleon and in collusion with Leclerc, Toussaint was seized at Brunet’s home and sent to the state prison, Fort de Joux. There he met his death in April 1803.

Cite This Article

"Toussaint Louverture: Tyrant or Liberator?" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

July 27, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/toussaint-louverture>

More Citation Information.