“We will whip the damned hounds yet.” — AP Hill

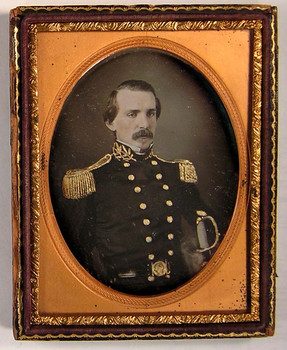

If George Thomas was the best Union general you’ve probably never heard of, A. P. Hill was the best Confederate general you’ve probably never heard of. Gallant “Little Powell” was very different from his fellow Virginian in build, temperament, and politics. Though they both opposed slavery (AP Hill never owned any slaves), AP Hill always knew that his first loyalty was to his native state, and was contemptuous of any bullying Yankees who thought they could justify killing Southerners to enforce Northern views.

Ambrose Powell Hill was born a son of the Virginia gentry, whose lineage in Virginia dated back to the seventeenth century, and as befit those roots his father raised him on horseback, a junior cavalier. He was quick and strong intellectually, well-schooled, though with an adolescent (and lasting) skepticism about religion (he nevertheless, as a matter of course, attended Episcopal services while in the Confederate army). That skepticism came not from his native Anglicanism but from a Baptist preacher who converted AP Hill’s mother to a piety of worldly renunciation, prohibiting virtually all forms of jollity such as a young man might enjoy. AP Hill loved his mother, but he didn’t love Calvinism. AP Hill would be one of those who didn’t think much of Stonewall Jackson.

But he did, as a young man, think a lot of heroism and battles. Early on in his life he had adopted the Latin tag “Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori” as his own (and his patria was always unmistakably the land in which he had been born and raised, Virginia). He wanted a career of military glory, and won an appointment to the U. S. Military Academy. His studies at West Point caused him no difficulties, and though a sociable cadet, with a few serious demerits early on, he was dutiful enough to recover his class standing.

In the summer before his third year at the Academy, however, he made a mistake that would plague him all his life. While on leave in New York City the sociable young cadet apparently contracted a social disease. Not only was the disease debilitating—and humiliating—at the time (he had to be sent home to recover), it later led to the ending of one serious courtship, and undermined his health for the rest of his life. Under the stresses of constant campaigning during the War Between the States, the erosion of his constitution, thanks to this disease, made him a man physically used up by 1865. The more immediate consequence of his indiscretion was that AP Hill graduated a year behind his entering class, which had rushed off to fight in Mexico. AP Hill was sent to Mexico too—the only man of the class of 1847 to be sent south of the border (perhaps the military authorities felt sorry for him)—but it was in relief of his 1846 classmate Thomas J. Jackson, who had already scooped up the battlefield honors AP Hill craved.

The young second lieutenant of artillery embarked in flamboyant style. He wore a fire red shirt (his red calico battle shirts would become a signature during the War), blue pants with a holstered sidearm on each hip, and another pair of handguns (and a knife) tucked into his belt. As a signature of rank, he had a saber clanking at his side. His pants were tucked into spurred boots, and on his head: a sombrero. Despite this get up, there is no record of any American sentry mistaking him for the enemy.

AP Hill did, however, get a small taste of combat in the mopping up operations, more than a small taste of typhoid fever (which nearly killed him), and a gentleman’s taste for the senoritas of Mexico, whom he ranked highly. He remained a sociable fellow.

The following year he was stationed at Fort Henry, in Maryland; then he was transferred to Florida, where he spent nearly six years (as well as a year off patrolling the Texas border) absorbing whatever diseases the humid, swampy Seminole country could throw at him. In 1855, he was sent home to Virginia to recuperate, and when his strength returned he found more amenable employment just across the Potomac. He was assigned to the office of the United States Coast Survey (run by the U.S. Navy) in Washington, D.C. His experience on engineering projects in the Florida swamplands made him a suitable candidate, and though AP Hill’s dreams were of martial glory, not desk-bound competence, he proved an expeditious administrator.

Not surprisingly, he also proved a social success in Washington with his easy and refined manners. In 1859, they were enough to win him the hand of a striking young widow nine years his junior, Kitty Morgan McCIung (AP Hill always called her Dolly, a name her mammy had given her), a belle of the Kentucky blue grass. Dolly’s brother, future Confederate cavalry officer, John Hunt Morgan, was AP Hill’s best man, and his new bride brought AP Hill back, at least physically, to the Episcopal Church. They made a splendid couple, and did indeed (as far as the marriage went) live happily ever after—ever after, in this case, ending with AP Hill’s premature death. Dolly bore AP Hill four daughters, one of whom died during the war.

A not-so-reluctant secessionist – AP HILL

At the end of March 1861. A little more than two weeks before Virginia seceded, AP Hill resigned from the army. For AP Hill it was a matter of facing facts: Virginia would not abandon her fellow Southern states—and AP Hill’s paramount loyalty was to his family and his native soil.

AP Hill’s ambition was to be a general in Virginia’s armed forces, but the Old Dominion was full of officers with West Point educations. Instead, in May, he was commissioned a colonel in the Confederate army, given command of a regiment of infantry, and issued orders to whip them into shape at Harpers Ferry. He did so wearing swashbuckling boots, his red battle shirts (hand-sewn by his wife), buckskin gauntlets, and a black felt hat. He would be distinguished in battle, at least sartorially.

He trained his men hard, but won them over by his easy manner and his sincere concern for their welfare (once even rounding up cattle on his own after the commissary officer told him there was no beef to be had). He proved capable from the start, a colonel who executed his orders with efficiency (no small accomplishment with newly raised troops).

In February 1862, AP Hill’s skill, if not yet his combat leadership (he had been on the field at Manassas but his troops were not engaged), won him promotion to brigadier general. His new assignment was to block the advance of George B. McClellan’s massive Union host up the Virginia Peninsula. He saw his first real action of the war at Williamsburg on 5 May 1862, in a fierce collision of blue and grey. AP Hill led his men from the front, charging into battle with pistol raised, and, rather confusingly, wearing a blue shirt rather than a red one.

The field was a mess of mud and rain, but the Confederates drove the Federals back to a line of felled timber. With ammunition running low, AP Hill ordered a bayonet charge that scattered the Federals. The young brigadier earned the plaudits of those who saw him directing troops through the storm of lead, “erect, magnificent, the god of war himself, amid the smoke and the thunder.

His performance won him promotion again. Before the month was out, he was a major general, the youngest in the Confederate army, and was given command of its largest division, which AP Hill dubbed “the Light Division,” no doubt thinking it gave the unit a certain panache. Its brigadier generals certainly did, including men like Maxcy Gregg, commander of the 1st South Carolina. A lawyer in civilian life, Gregg was also one of those Southern renaissance men who was by turns, and among other things, a classicist, an ornithologist, and an astronomer with his own private observatory. The first brigade was full of professional men—doctors, lawyers, prominent businessmen— who had gallantly reassured the ladies of Richmond that “We go cheerfully to meet the foe; rest assured our vile enemy shall never desecrate your homes until they have first trodden over the bodies of our regiment.”

“Always ready for a fight”

After Robert E. Lee took command of the army defending Richmond, he called a conference among generals James Longstreet, A. P. AP Hill, D. H. AP Hill, and Stonewall Jackson, who stunned the others by his arrival (everyone believed he was still in the Valley). Lee outlined his daring plan to attack McClellan’s right flank; the lead element would be Stonewall Jackson’s. Jackson said he could withdraw his men from the Valley and have them ready to attack on 25 June, only two days away. Longstreet and Lee demurred that surely Jackson needed more time. Jackson agreed to the morning of 26 June. As it happened, Jackson would be very, uncharacteristically, late.

By 3:00 p.m. on 26 June, AP Hill decided he had waited long enough. He ordered his men forward, inaugurating the Battle of Mechanicsville. AP Hill’s impetuosity meant his men had to cross open ground under deadly fire. Artillery captain “Willie” Pegram rushed up support, but Pegram was so badly outnumbered—by about thirty batteries (which quickly pinpointed his position) to six—that he lost more than half his artillerists and four of his six cannons in a matter of minutes.

AP Hill’s action was a mistake, but the Confederates were inspired by the line of bluecoats retreating before them. The Federals reformed at heavily fortified Beaver Dam Creek: 30,000 men in a virtually impregnable position. AP Hill was not impressed. He ordered his men to attack. With Lee and Jefferson Davis looking on, and dusk falling on the field, AP Hill threw his forces at the Yankee right flank. His men “made the AP Hills and valleys and woods ring with their Confederate yells as they eagerly pressed forward with anticipation of coming victory/” But victory eluded them under the withering fire and the entangling brambles that kept them from reaching the Union line.

AP Hill, however, refused to give up. Failing on the right and center of the Union line, he tried the left—and the results were worse: Union fire ripped through the charging Confederates. Hill had shown more ardor and personal courage than tactical brilliance at Mechanicsville, but Lee did not criticize him. He valued Hill’s spirit. If there was any blame to be laid it was with Jackson who had not only not arrived, not only badly underestimated how long it would take him to reach the field, but had failed to get a messenger to Lee to tell him where he was. Jackson and his men were simply worn out mentally and physically; they had asked too much of themselves.

What to do next? The answer, it turned out, was to walk in and seize the Federal position at Beaver Dam Creek. The Union General Fitzjohn Porter had left only a token holding force and withdrawn his men in the night. So it was victory after all—at least on this field.

Porter had withdrawn behind Powhite Creek at Gaines’s Mill. The Confederates pursued him and gave him battle once again. Maxcy Gregg’s brigade had charged, pushing the Federal skirmish line back, but only to get his own men pinned down by Federals in positions on the high ground. What neither Hill nor Gregg knew was that the Federal line was three lines deep, entrenched or fortified at each line, a total of about 35,000 men, approachable only across a field of fire that was a muddy, swampy mess.

Hill drew up his entire force to come to Gregg’s rescue. Longstreet would be in support on his right, and Jackson, reportedly soon to arrive, would be on his left. Longstreet had the lead but his troops got bogged down by the terrain, and were further impeded by Union artillery fire. Hill, champing at the bit again, decided he could not wait. His own artillery opened fire and his men went charging in—unsupported by either Longstreet or Jackson.

Gregg’s men got into the first Union entrenchments, but were pushed out in fierce hand-to-hand fighting. All along the line, the Confederates surged forward only to melt back under Union fire—and then surged forward again. The Light Division was becoming considerably lighter. Hill did not recall his troops, but sent orders for them to cease the offensive and hold their bloody ground. Jackson at last arrived, still apparently dazed from exhaustion, and at 7:00 p.m. Lee sent his combined forces against the Union position. The Federals were driven back until darkness became their shield. But the position at Gaines’s Mill now belonged to the Confederates.

Hill and his Light Division had distinguished themselves in these, the opening of the Seven Days’ Battles, and they would continue to do so. It was a handsome compliment to the young major general that his was the hardest fought regiment in the army; his men were the best in pursuit of the Federals and the most reliable at taking positions.

Another compliment to his leadership was when he rode up to Lee and Jefferson Davis who were surveying the battlefield under enemy fire. Hill said with less than his usual charm, “This is no place for either of you, and as commander of this part of the field I order you both to the rear!” “We will obey your orders,” said Jefferson Davis, with a slight smirk. Artillery fire burst closer, but Davis’s horse and Lee’s trotted only a short distance away. AP Hill charged back, “Did I not tell you to go away from here, and did you not promise to obey my orders? Why, one shot from that battery over yonder may presently deprive the Confederacy of its President and the Army of Northern Virginia of its commander!” “Little Powell” was more than big enough to stand up for good sense.

At the Battle of Frayser’s Farm, AP Hill’s (and Longstreet’s) troops again bore the brunt of the fighting, with AP Hill storming about the battlefield on his horse Prince, encouraging, leading, and even grabbing the standard of the 7th North Carolina and telling them to charge with him or he would die alone. His leadership was inspirational, but at Frayser’s Farm he also showed the tactical skill that Lee hoped to see in him. AP Hill was proving he deserved his stars.

Battles front and rear

Unfortunately, Hill’s next enemy was James Longstreet. After a Richmond journalist wrote up Hill’s praises to the exclusion of Longstreet, Longstreet had his aide Moxley Sorrel write an indignant reply. Hill was now affronted at what he thought was Longstreet’s slighting of the Light Division. Hill refused to communicate with Longstreet’s command. Longstreet put him under arrest and Hill challenged Longstreet to a duel. General Lee reconciled the two commanders, at least to the point of tolerating each other, and then sent Hill to join Stonewall Jackson.

Jackson’s men were moving north to defend Virginia from the blustering Union general John Pope. Despite orders from Lee to keep Hill well apprised of his plans, Jackson pursued his council of one, with comically disastrous results. Because some generals were informed of changes in movements and others were not, their marching orders became a hash work of confusion. Jackson was definitely not on his best form. It didn’t help that Jackson and Hill didn’t like each other. AP Hill had not forgotten Jackson’s failures to support the Light Division during the Seven Days campaign; and the Cromwellian Jackson found it hard to appreciate the Cavalier AP Hill.

But at the Battle of Cedar Mountain, six miles south of Culpepper, it was Hill and his troops who again carried the day. Jackson’s men had engaged the enemy first; when Hill arrived, it was with a perfectly timed and placed assault; the Light Division smashed the Federals and led the pursuit. The battlefield brought Hill a new charger, a grey stallion named Champ. It did not, however, bring him an improved relationship with Jackson.

Nevertheless, Jackson was dependent on Hill’s stalwart leadership at the Battle of Second Manassas, which followed on 29 August 1862. Hill’s performance was not perfect—in arranging his troops he had left a dangerous 175 yard gap within his front line—but it was bravely led, hard fought, and, against heavy odds, successful. Jackson had perhaps 18,000 effectives on the field. Marching towards him were 63,000 men under the command of Union General John Pope.

AP Hill’s men withstood the first Union assault and then gallantly counterattacked, scattering the blue-coats. But this was only the opening round. The Federals came back in force, and the violent collision of armies became one of hand-to-hand combat, among bursting artillery shells, crackling muskets, and smoky fires ignited in the woods and grass. Though some of the Confederates were reduced to fighting with rocks, bayonets, and muskets used as clubs (in the absence of ammunition) they refused to buckle.

In the bloody ebb and flow of battle, the Confederates repelled Federal attacks all day long. AP Hill, however, had to confess to Jackson, via a messenger, that if the Federals mounted another attack, he would do the best he could, but with no ammunition, his men would be hard-pressed.

Henry Kyd Douglas, an aide to General Jackson, remembered that “Such a message from a fighter like AP Hill was weighty with apprehension.” Jackson replied, “Tell him if they attack him again he must beat them.” Douglas and Jackson rode to meet AP Hill and listened to his concerns, to which Jackson said: “General, your men have done nobly; if you are attacked again you will beat the enemy back.”

Suddenly musket fire erupted along AP Hill’s position. “Here it comes,” AP Hill announced, and immediately rode off to join his men. Jackson called after him: “I’ll expect you to beat them.”

Beat them he did, and when AP Hill sent a message to Jackson confirming his success, a grim smile creased Jackson’s face. “Tell him I knew he could do it.”7

The next day the Federals came again, but this time, forming up alongside Jackson were James Longstreet’s men, and when Longstreet turned them loose, the grey tide swept the bluecoats away, with AP Hill’s men jumping into the counterattack. And AP Hill fought well again—and again with a shortage of ammunition—at Ox AP Hill on 1 September 1862.

Despite such victories, the mountain-bred Calvinist and the Piedmont cavalier fell into another dispute over marching orders. Jackson put AP Hill under arrest, though he did have the good sense to release him before action at Harpers Ferry and allowed AP Hill to resume his command until the end of the Maryland campaign.

Bloody roads

AP Hill seized Harpers Ferry and was given the task of arranging and executing the terms of the Yankee surrender (which under the chivalrous AP Hill were very liberal) while Jackson moved north into the bloodiest day’s fighting of the war at Sharpsburg. But it was AP Hill who once more turned the tide. Moving to the sound of the guns, he force-marched his men to the rescue of Lee’s arm}-, making a dramatic arrival at the battle field, sweeping away Ambrose Burnside’s bluecoats who might otherwise have broken the Confederates, and convincing General McClellan not to press his luck against the valiant Army of Northern Virginia. When the Confederates withdrew, it was AP Hill’s men who slapped the pursuing Federals a bloody repulse.

The campaign concluded. Hill demanded a hearing on his arrest by Jackson. Lee replied that no trial was necessary, because surely an officer of Hill’s caliber would never disappoint General Jackson again. Hill was not mollified and reiterated his demand for a hearing. But even the stubborn Jackson, at this point, wanted to let the matter drop. Lee met with his generals, and though he could not reconcile them, he at least restored them to a status of receiving each other with cold and reluctant civility. Lee, in the meantime, named Longstreet and Jackson as the commanders of the First and Second Corps of the army. “Next to these two officers,” Lee wrote to Jefferson Davis, “I consider A. P. Hill the best commander with me. He fights his troops well, and takes good care of them.”

At Fredericksburg, Hill was charged with anchoring the right side of the Confederate line, but he was apparently distracted with grief. His eldest daughter had died of diphtheria, and the normally ardent commander was noticeably absent from the action. In arranging his line, he had allowed it to be separated by a wide patch of swampy woods, leaving a gap in the center of about 600 yards. When the Federals crashed into Hill’s line, they inevitably found the gap, pouring into Maxcy Gregg’s unprepared men who were arrayed behind it as a reserve. Gregg was killed, but the Confederates bravely closed ranks and plugged the gap, driving the Federals back and ending the major action on Hill’s side of the field.

Before the Light Division left Fredericksburg, Hill had recovered his composure, and his men donated $10,000 to help the poor in the battered, old, picturesque town. It was a typical, chivalrous gesture from Hill’s command.

At Chancellorsville, despite their personal animosities. Hill and Jackson cooperated as well as they ever did, with the Light Division joining Jackson’s audacious sweep across the Federal front, and filing in as the reserve to pursue the Federals that Jackson drove from the field.

But just as Jackson was shot down at dusk scouting ahead of Confederate lines, so too Hill and his staff were shot at by Confederate troops only fifty yards away. Hill had been riding ahead calling out for the Confederates to cease fire. But in the darkness, the grey-clad infantry thought it was a Yankee trick. Hill plunged from his horse at the crackle of close-range musketry and was miraculously unscathed. When he heard that Jackson was hit, he went immediately to help his commander. It was Hill who cradled Jackson’s head and bandaged his arm to stanch the bleeding. Hill called for a surgeon, before moving out to secure the position around Jackson.

Unfortunately, Hill himself was then wounded by Federal shell fire. He nevertheless regained his horse and directed troops into position until he could be relieved by J. E. B. Stuart as temporary commander of the Second Corps. Hill returned to command four days later, but Jackson would not return at all. In his final feverish hours he was heard to call out: “Order A. P. Hill to prepare for action!”

After Jackson’s death, Lee appointed General Richard Ewell, a Jackson favorite, commander of the Second Corps. It was a popular choice among Jackson’s men. But Lee had a promotion for A. P. Hill as well. In a letter to President Jefferson Davis, Lee had said that Hill was “upon the whole… the best soldier of his grade with me,” recommended him for promotion to lieutenant general, and proposed that the Army of Northern Virginia should now be divided into three corps, rather than two. Jefferson Davis approved, and the Third Corps went to A. P. Hill.

Corps commander

The Third Corps’ first action was Gettysburg, but their corps commander was terribly sick, ashen-faced, tired, and perhaps distracted by pain. Nevertheless, it was his men who stumbled into the Yankees first and precipitated the greatest battle of the war. As dusk crept up on the first day of battle, Lee asked Hill whether his men could press the attack. The normally belligerent cavalier said no, his men had marched and fought themselves out. It was then that Lee turned to the usually equally belligerent Richard Ewell who came to the same conclusion about the Second Corps. It was not an auspicious beginning for the newly configured Army of Northern Virginia, and these were not the answers that Stonewall Jackson would have given.

On the second day, Hill’s men were to act in support of Longstreet. The troops of the Third Corps most deeply involved, those under General Richard Anderson, were badly managed—in part because Hill assumed that Longstreet would coordinate their attack and Longstreet assumed that they would remain under Hill’s direction. Hill again seemed insufficiently aggressive, dispirited in the wake of Longstreet’s sluggishness, and disengaged from his responsibilities.

On the third day, Hill, unlike Longstreet, was an enthusiast for the planned assault on the Union center. He asked permission to lead the attack and Lee should have given it to him and allowed Hill to commit the entire Third Corps to the charge (instead of holding most of it in reserve—a role that would have been better served by Longstreet, who was always better at counterpunching). Had “Little Powell” led the charge at the Union line, with the entirety of the Third Corps, with all the celerity of a commander convinced of the plan’s worth, the Confederates might have won the Battle of Gettysburg.

Instead, a surly, insubordinate Longstreet was charged with making an attack he was convinced would fail, and which he did everything possible to delay and cancel. Longstreet was the wrong man for the job; Hill would have been the right one. Moreover, Hill’s relationship with Longstreet was very nearly as cold as his relationship had been with Jackson; and as on the second day, neither commander took responsibility for directing Hill’s men in the attack; each general assuming it was the other’s prerogative or responsibility. The result, of course, was a disaster.

On 14 October 1863, Hill thought he had found his redemption, when he caught a large body of Federals napping at Bristoe Station, Virginia, not far from Manassas. But in his haste to attack the Federals before they could escape, he neglected to reconnoiter the ground. His precipitate assault did, indeed, catch the Federals by surprise, but as General Henry Heth’s division was hurried to pursue the fleeing Yankees, it ran into a flank attack by blue-coated troops concealed behind a railroad cutting. Hill had seen the risk—though he had only a vague idea of enemy numbers behind the railroad tracks—but assumed that his artillery could keep the Federals at bay, and was simply eager to fight. He didn’t realize that concealed behind those tracks were three Union divisions that had a clear killing ground to enfilade the attacking Confederates.

When the entrenched Federals opened fire, cutting a swathe through the grey-clad ranks, the Confederates reformed and redirected their attack at the Yankees behind the railroad tracks. It was a brave but dangerous choice. They managed to break through the first Union line, but were trapped by the second and driven back with heavy losses. James I. Robertson, one of Hill’s best biographers, estimates that Hill lost a man—killed, wounded, or captured—every two seconds of the battle. Hill’s impetuosity had its place, but not here, and probably never as a corps commander, a role that actually never suited Hill. He needed to be in among the fighting men, not directing the movements of a corps.

Hill knew he had blundered and confessed as much in his official report. The next day, after the Yankees had continued their retreat, Hill rode over the ground with Lee and repeatedly apologized for his costly error. Lee offered Hill no excuses. But as was often the case, he issued no sharp rebuke either, knowing it was beside the point. Hill knew he had erred, and knew he had disappointed Lee. Finally Lee said, “Well, well.

General, bury these poor men and let us say no more about it. Hill, however, could never let the dead bury their dead at Bristoe Station. For the rest of the war, his failure there, and his increasingly faltering health, depressed his spirits—and his effectiveness.

On the first day of the Battle of the Wilderness (5 May 1864), Hill fought his corps like his old self (even if physically he was ailing), directing his troops with remarkable skill in a very hot fight. But his physical disabilities began to tell that night, and not enough was done to prepare the next day. Hill had expected (and so did Lee) that Longstreet would be up with reinforcements. Longstreet, however, was late, and when the Federals hit Hill’s battered lines on the morning of 6 May, the Southerners were unprepared for the ferocious attack. Though in tremendous pain, Hill gallantly rode up and down the lines encouraging the troops, organizing the defense, even directing batteries of enfilading artillery fire at the front. When Longstreet’s men finally rolled onto the field. Hill led his men in a counterattack against the Federals (so far in advance was Hill that he was nearly captured by lead units of the Union army).

Two days later, an enfeebled Hill asked Lee to give command of the Third Corps to another general, at least temporarily. Lee reluctantly granted his request, giving the Third Corps to Jubal Early, while Hill remained with the troops aboard an ambulance. He eventually returned to command, and battered as he was, he and Lee endured together, the great slogging match between the counterpunching Army of Northern Virginia and the relentless, hard-pounding Ulysses S. Grant, all the way through most of the siege of Petersburg.

On 19 June 1864, a woman saw Lee and Hill during Sunday services at an Episcopal church. The woman described Hill as “a small man, but [one who] has a very military bearing, and a countenance pleasing but inexpressibly sad.” Hill’s physical state was an apt reflection of the state of the Confederacy, battling on, with a remembrance of past happiness and nobility, now turned inexpressibly sad and worn down. But as Lee proved himself a master of defensive tactics in these final months, so did Hill, whose leadership rebounded even if his health did not.

By the winter of 1864, his strength, vitality, and even his ability to concentrate were visibly failing. The swashbuckling Hill now found it difficult and painful to mount a horse. But he remained intent on his duties, and rode his lines. He was returning from an early morning conference with Lee on 2 April 1865 when he met his fate. The Confederate line had been broken and Hill was determined to rally his men. Lee admonished him to be careful. Careful was not a word easily applied to Hill.

In his search for the front, the desperately sick Hill rode along a no-man’s land. Along the way, he captured and sent to the rear, under escort, two Federal infantrymen. With his remaining companion, courier George Tucker, he rode on, until he found two more Yankees leveling muskets at him. Hill drew a revolver and called on them to surrender. Instead, the blast of a .58 caliber bullet smashed through Hill’s heart, killing him.

When Lee heard the news, he replied sadly, “He is now at rest, and we who are left are the ones to suffer.”12 Like Jackson in his delirium. Lee in his final moments also called for “Little Powell”: “Tell A. P. Hill he must come up.” Perhaps no other general, besides Lee, was so much a part of the Army of Northern Virginia.

General James Alexander Walker said of him that “of all the Confederate leaders [Hill] was the most genial and lovable in disposition… the commander the army idolized.”

Hill fought virtually the entire war. He represented the Virginia of manners, courtly graces, chivalry, and patriotism. If he is little remembered today, compared with Jackson, Longstreet, and J. E. B. Stuart, he deserves to be recognized for the gallant Southern soldier that he was.

Cite This Article

"Confederate General A.P. Hill (1825-1865)" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

July 27, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/ap-hill-1825-1865>

More Citation Information.