The Battle of Port Gibson happened on May 1, 1863, near Port Gibson, Mississippi as part of the Vicksburg Campaign of the American Civil War.

MOVING INLAND: BATTLE OF PORT GIBSON

The first day ashore, Grant pushed McClernand two miles inland to high, dry ground and on toward the town of Port Gibson, where a bridge across Big Bayou Pierre led to Grand Gulf (which Grant coveted as a supply base on the Mississippi). Meanwhile, Grant oversaw the continuous transport of more of his troops across the Mississippi well into the night. Aided by the light of huge bonfires, McPherson’s soldiers were transported until a collision between two transports at three o’clock in the morning stopped the operation until daylight.65 Back upriver, Sherman was beginning to move south but remained worried about the long, vulnerable supply line. There was a reason to be worried. As James R. Arnold observes, “Grant was at the end of an exceedingly precarious supply line, isolated in hostile territory, positioned between Port Hudson and Vicksburg—two well-fortified, enemy-held citadels—outnumbered by his enemy, and with an unfordable river to his rear. Few generals would have considered this anything but a trap. Grant judged it an opportunity.”

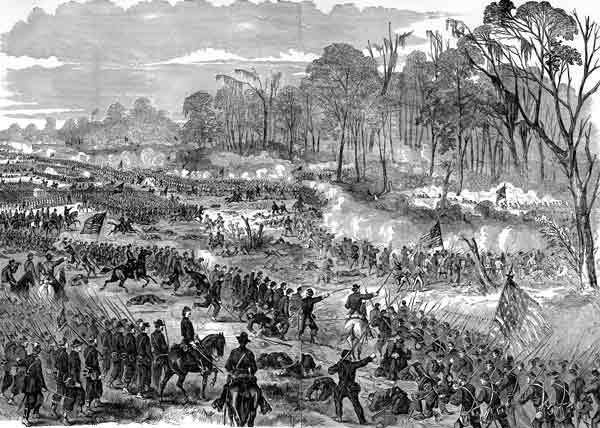

The next day, May 1, brought conflict and the first of Grant’s five victories leading to the siege of Vicksburg—the Battle of Port Gibson.67 Two Confederate brigades, which had belatedly marched as many as forty-four miles from near Vicksburg, and the garrison from Grand Gulf had crossed the bridge over the North Fork of Bayou Pierre at Port Gibson. They confronted McClernand’s troops about three miles west of the site of the Battle of Port Gibson. McClernand split his forces along two parallel roads leading toward town and ran into strong opposition. General Bowen arrived from Grand Gulf to command the defenders.

The Confederate left fell back under intense attack from three of McClernand’s divisions as Union sharpshooters picked off the brave and effective rebel gunners manning the defenders’ artillery. Following the initial rebel retreat, McClernand and the visiting governor of Illinois, Richard Yates, delivered victory remarks and did some politicking with the troops. Grant put an end to those proceedings and ordered the advance to resume. Meanwhile, Grant had reinforced McClernand’s left wing on the northern road with two of McPherson’s brigades, and that wing, in the face of persistent enemy artillery, likewise drove the Confederates back toward Port Gibson. The victory was confirmed the next morning, May 2, when Grant’s soldiers found Port Gibson abandoned by the Confederates, who had crossed and burned the bridges across Big Bayou Pierre (to Grand Gulf) and Little Bayou Pierre.

Although Grant’s troops were on the offensive all day at the Battle of Port Gibson, the two sides’ casualties were surprisingly comparable. Grant had 131 killed, 719 wounded, and twenty-five missing—a total of 875. Based on incomplete reports, the Confederate defenders had at least sixty-eight killed, 380 wounded, and 384 missing—a total of at least 892.

Despite narrow roads, hilly terrain, and dense vegetation that aided the defenders, Grant’s superior force had gained the inland foothold it needed and access to the interior. The battle set the tone for those that followed in the campaign and affected the morale of the winners and losers. Grant would consistently bring superior forces to each battlefield although his troops were outnumbered by the Confederates scattered around western Mississippi. From Vicksburg, Pemberton accurately and somewhat desperately telegraphed Richmond: “A furious battle has been going on since daylight just below Port Gibson. . . . Enemy’s movement threatens Jackson, and, if successful, cuts off Vicksburg and Port Hudson from the east. . . . ” With minimal losses, Grant was moving inland. Meanwhile, a rattled Pemberton sent an urgent message to his field commanders directing them to proceed at once but neglecting to say to where.

McClernand’s mid-battle political speech was not the only evidence of his incompetence and problematic attitude. His men went ashore with no rations instead of the standard three days’ worth. He rejected a brigadier’s recommendation that he attack the enemy flank and instead ordered a frontal assault. When Grant ordered McClernand’s artillery to conserve ammunition, an angry McClernand countermanded the order. Having just crossed the Mississippi to initiate a challenging campaign of unknown duration, a subordinate military commander would be expected to honor the commanding general’s concern about conserving ammunition for future contingencies. McClernand was setting himself up for a big fall. In fact, Stanton, aware of previous problems with McClernand, had sent Charles Dana a telegram on May 6 authorizing Grant “to remove any person who by ignorance in action or any cause interferes with or delays his operations.”

After his troops had quickly built a bridge across Little Bayou Pierre, Grant accompanied McPherson northeast to Grindstone Ford, the site of the next bridge across Big Bayou Pierre. They found the bridge still burning but only partially destroyed, and after rapid repairs, they crossed Big Bayou Pierre. Because Grant was now in a position to cut off Grand Gulf, the Confederates abandoned that port town and retreated north toward Vicksburg. At Hankinson’s Ferry, north of Grand Gulf, the Confederates retreated across a raft bridge over the Big Black River, the only remaining geographical barrier between Grant and Vicksburg.

On May 3, Grant rode into the abandoned and ruined town of Grand Gulf, boarded the Louisville, took his first bath in a week, caught up on his correspondence, and rethought his mission. He had learned of the success of Grierson’s diversionary mission and also of the time-consuming campaign of the incompetent Union general Nathaniel P. Banks up the Red River. He decided to deviate radically from his orders from General Halleck, which called for McPherson’s corps to move south to Port Hudson, await the return of Banks, and cooperate with him in the capture of that town—all before a decisive move on Vicksburg. Grant realized that he would lose about a month waiting to cooperate with Banks in taking Port Hudson and would gain only about twelve thousand troops from Banks. The intervening time, however, would give Confederates, under Department Commander Joseph E. Johnston, the opportunity to gather reinforcements from all over the South to save Vicksburg. So Grant decided instead to move inland with McPherson’s and McClernand’s corps, and he ordered Sherman to continue moving south to join him with two of his three divisions.

Before leaving Grand Gulf at midnight on May 3, Grant wrote to Halleck:

The country will supply all the forage required for anything like an active campaign and the necessary fresh beef. Other supplies will have to be drawn from Millikin’s [sic] Bend. This is a long and precarious route but I have every confidance [sic] in succeeding in doing it.

I shall not bring my troops into this place but immediately follow the enemy, and if all promises as favorably hereafter as it does now, not stop until Vicksburg is in our possession.

Grant was going for Vicksburg—now. Until Sherman’s troops arrived, Grant had only twenty-five thousand troops across the river to face fifty thousand Confederates in Mississippi with as many as another twenty thousand on the way.

When he moved inland to Hankinson’s Ferry at daybreak on May 4, Grant learned that McPherson’s men had captured intact the bridge across the Big Black River and established a bridgehead on the opposite shore. While awaiting the arrival of Sherman’s corps, Grant ordered McPherson and McClernand to probe the countryside, giving the enemy the impression that Grant would directly attack Vicksburg from the south. McPherson’s patrols discovered that the Confederates were fortifying a defensive line south of Vicksburg. With the arrival of Sherman and the bulk of his corps on May 6 and 7 (after a sixty-three-mile march from Milliken’s Bend to Hard Times and ferrying across to Grand Gulf), Grant was ready to move in force.

Realizing that Vicksburg by now was well defended on the south and that its defenders could flee to the northeast if he attacked from the south, Grant decided on a more promising but riskier course of action. As T. Harry Williams puts it, “the general called dull and unimaginative and a mere hammerer executed one of the fastest and boldest moves in the records of war.” He cut loose from his base at Grand Gulf, withdrew McPherson from north of the Big Black River, and ordered all three of his army’s corps to head northeast between the Big Black on the left and Big Bayou Pierre on the right. His goal was to follow the Big Black, cut the east-west Southern Railroad between Vicksburg and Jackson, the state capital, around the town of Edwards Station, and then move west along the railroad to Vicksburg. In what Thomas Buell calls “the most brilliant decision of his career,” Grant “would attack first Johnston and then Pemberton before they could unite and thereby outnumber him, the classic example of defeating an enemy army in detail.” Given the poor condition of the dirt roads, the tenuous supply situation, and the threat of Confederate interference from many directions, this plan, in the words of Ed Bearss, “was boldness personified and Napoleonic in its concept.” William B. Feis admires Grant’s craftiness: “From the outset, Grant designed his movements to sow uncertainty in Pemberton’s mind as to the true Federal objective. The key to success, especially deep in Confederate territory, was to maintain the initiative and make the enemy guess at his objectives.” Grant was determined not only to occupy Vicksburg but to trap Pemberton’s army rather than allow it to escape to fight again. As he would do later in Virginia, Grant stayed focused on defeating, capturing, or destroying the opposing army, not simply occupying geographic positions. This approach was critical to ultimate Union victory in the war.

General Fuller pointed out that not only was Grant’s plan daring and contrary to his instructions from Halleck, but that, just as importantly, he insisted that his commanders move with haste to execute it. His orders to them in those early days of May were filled with words urging them to implement his orders expeditiously. He clearly wanted to move quickly inland to negate any forces other than Pemberton’s, destroy Vicksburg’s supply line, and then quickly turn on Vicksburg with his own rear protected.

As Grant moved inland, he planned to live off the previously unmolested countryside. His troops slaughtered livestock and harvested crops and gardens to obtain food and fodder. They also gathered an eclectic collection of buggies and carriages to assemble a crude and heavily guarded wagon train that would carry salt, sugar, hard bread, ammunition, and other crucial supplies from Grand Gulf to Grant’s army. Grant would depend on those intermittent and vulnerable wagon trains to meet some of his needs for two weeks until a supply line was opened on the Yazoo River north of Vicksburg on May 21. From May 8 to 12, Grant’s army moved out of its Grand Gulf beachhead and up this corridor, with McClernand hugging the Big Black on the left and guarding all the ferries, Sherman in the center, and McPherson on the right. They gradually swung in a more northerly direction (pivoting on the Big Black) and moved within a few miles of the critical railroad without serious opposition. Then, on May 12, McPherson ran into stiff opposition south of the town of Raymond. Aggressive assaults ordered by Confederate Brigadier General John Gregg, who believed he was facing a single brigade, threw McPherson’s soldiers into disarray. Strong counterattacks led by Logan drove the outnumbered Confederates back into and through Raymond. Gregg’s aggressiveness cost him one hundred dead, 305 wounded and 415 missing, for a total of 820 casualties. McPherson reported his casualties as sixty-six killed, 339 wounded, and thirty-seven missing, for a total of 442. Grant’s campaign of maneuver and his concentration of force were resulting in progress at the cost of moderate casualties.

Even more importantly, Grant’s daring crossing of the Mississippi and inland thrust were sowing confusion at the highest levels of the Confederacy. Pemberton, in command at Vicksburg, was caught between conflicting orders from President Jefferson Davis and his department commander, General Joseph Johnston. Davis told Pemberton that holding Vicksburg and Port Hudson was critical to connecting the eastern Confederacy to the Trans-Mississippi. The Northern-born Pemberton, who had been eased out of his Charleston, South Carolina, command for suggesting evacuation of that city, decided to obey the president and defend Vicksburg at all costs. He did this despite orders on May 1 and 2 from Johnston that, if Grant crossed the Mississippi, Pemberton should unite all his troops to defeat him. Grant was the beneficiary of Pemberton’s decision because Pemberton kept his fifteen brigades in scattered defensive positions behind the Big Black River while Grant moved away from them toward Jackson. Meanwhile, Johnston, sitting in Tullahoma, Tennessee, with little to do, moved to oppose Grant only when belatedly ordered to do so by Davis and Secretary of War James A. Seddon on May 9—and he did so with only three thousand troops at first.

This article is part of our larger selection of posts about the Civil War. To learn more, click here for our comprehensive guide to the Civil War.

Would you like to learn the complete history of the Civil War? Click here for our podcast series Key Battles of the Civil War

Would you like to learn the complete history of the Civil War? Click here for our podcast series Key Battles of the Civil War

Cite This Article

"The Battle of Port Gibson in the Vicksburg Campaign" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

July 27, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/battle-of-port-gibson>

More Citation Information.