Students often ask if Founding Father George Clinton of New York is any relation to Bill and Hillary Clinton. Both are “from” New York, and to students who have little understanding of even contemporary events, this is an obvious question. This answer, of course, is no, but it illustrates how little most students know about George Clinton (and also about Bill Clinton, who was born William Jefferson Blythe III).

George Clinton’s ancestors had served the king during the English Civil War of the mid-seventeenth century and then supported the Glorious Revolution of 1688. Clinton himself was born in 1739 to Charles and Elizabeth Clinton of Ireland. His parents immigrated to New York in 1731 and established a farm in Ulster County. Clinton had no formal education, but his father provided his son with private tutors, and he was a bright student. The colonial governor of New York recognized Clinton’s talent and, remarkably, appointed him clerk of the court of common pleas of Ulster County when Clinton was only nine years old. The expectation was that the young Clinton would assume the job once the senior clerk died. Clinton officially assumed the post in 1759, at the age of twenty, and he remained in the position for the rest of his life, a fifty-three-year tenure.

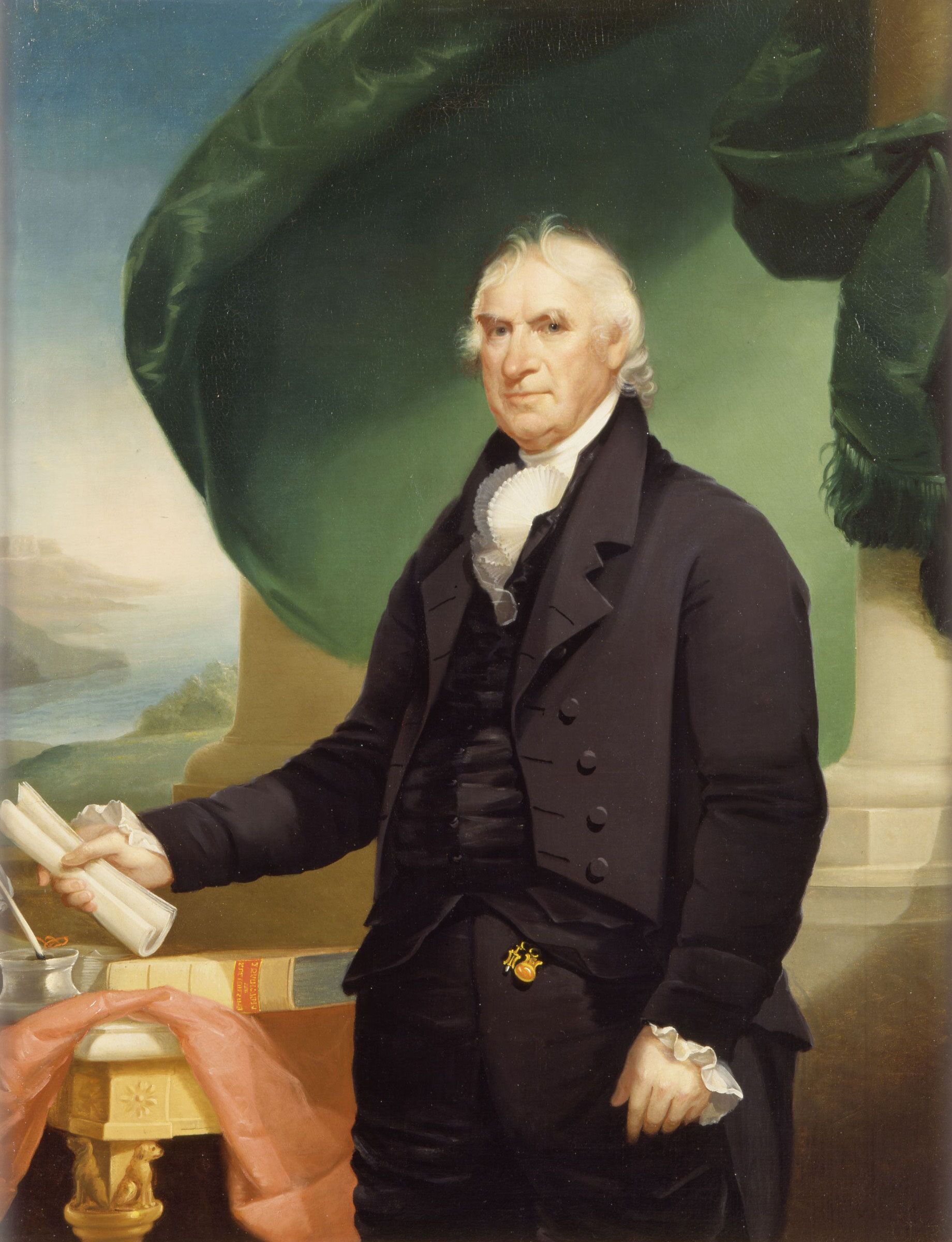

Like other frontier men of his generation, George Clinton took part in the French and Indian War. At eighteen, he joined the crew of the privateer Defiance and served on a one-year tour in the Caribbean. When he returned to New York, he became a subaltern or junior officer in his brother’s militia company and participated in the British assault on Montreal in 1760. He subsequently left the military and returned to New York to practice law. Clinton emerged as a leading colonial attorney, but augmented his profession with milling and surveying. After his marriage to Cornelia Tappen in 1770, he bought an estate overlooking the Hudson River. He was elected to the New York Assembly in 1768 and became an ardent defender of freedom of speech and freedom of the press. Clinton helped lead the patriot cause in the New York legislature, declared Parliamentary taxes unconstitutional, and stated in 1775 that “the time was nearly come, that the colonies must have recourse to arms, and the sooner the better.”

This type of language led the people of New York to send him to the Second Continental Congress in 1775. He was also appointed brigadier-general in the New York militia. He supported Washington’s appointment as commander-in-chief and hosted a dinner for him during Washington’s trip north to Boston in 1776. While in Congress, Clinton reportedly wished for a dagger to be planted in the heart of George III, the “tyrant of Britain.” He supported the Declaration of Independence but had to leave the Congress and attend to military matters before he could sign the document.

George Clinton was charged with the defense of the Hudson River, but he was not an effective military commander. Though successful in raising enlistments, he lost Fort Montgomery and failed to prevent the British from burning the town of Esopus in 1777. He wrote to the New York legislature that he contemplated resigning because “I find that I am not able to render my Country that Service which they may have Reason to expect of me.” Some New Yorkers chaffed at his actions in defense of the cause.

He confiscated loyalist property and, according to one eyewitness, was brutal in his treatment of anyone who resisted American independence. Clinton was commissioned brigadier-general in the Continental Army but left the military in 1777 after being elected governor of New York.

Anti-Federalist governor

George Clinton defeated Philip Schuyler—Alexander Hamilton’s future father-in-law—for governor, and this set the stage for a political rivalry that lasted for the rest of his life. Schuyler was a wealthy and powerful New Yorker with connections to the “best” families in the state. Clinton was seen as a country bumpkin and an outsider. John Jay, future Supreme Court Chief Justice and author of three essays in the Federalist, wrote after the election that “Clinton’s family and connections do not entitle him to so distinguished a pre-eminence.” Still, the power in New York shifted to the second generation New Yorker from Ulster County. He served his state well during the war and managed state finances with success.

His guiding hand in Indian policy, retributive treatment of Loyalists, and low taxes (in fact, New York freeholders did not pay taxes for eighteen years under Clinton), made him a popular governor, and he was reelected to the office for six consecutive terms.

George Clinton developed a strong political following of young, like-minded men, mostly through patronage, and this group became outspoken opponents of a strong central government. The Articles of Confederation suited them well. New York had commercial advantages, and Clinton did not want a stronger central authority to erode his political power, nor did he want New York placed in a subservient position vis-à-vis other Northern states. But his motives were not purely personal. From the time leading up to the Revolution, Clinton believed the states offered the best protection for individual liberty, and like other Founding Fathers, Clinton considered his state to be his country.

When the Constitutional Convention wrapped up its work in September 1787, Clinton published a series of letters in the New York press under the name “Cato” challenging the proposed Constitution. He criticized it for consolidating the states into one general government which could not, in his estimation, protect the lives, liberty, and property of the people. In his third essay, Clinton wrote:

The strongest principle of union resides within our domestic walls. The ties of the parent exceed that of any other. As we depart from home, the next general principle of union is amongst citizens of the same state, where acquaintance, habits, and fortunes, nourish affection, and attachment. Enlarge the circle still further, and, as citizens of different states, though we acknowledge the same national denomination, we lose in the ties of acquaintance, habits, and fortunes, and thus by degrees we lessen in our attachments, till, at length, we no more than acknowledge a sameness of species. Is it, therefore, from certainty like this, reasonable to believe, that inhabitants of Georgia, or New Hampshire, will have the same obligations towards you as your own, and preside over your lives, liberties, and property, with the same care and attachment? Intuitive reason answers in the negative.

George Clinton, as governor, made a strategic error. He hoped to defeat the Constitution, but feared he might not have the votes at a state convention, so he delayed calling one. If, however, he had used his enormous influence to defeat the Constitution in New York before Virginia and Massachusetts made their votes, he might have swayed those states to join the Anti-Federalist camp.

The New York ratification finally met in June 1788. Clinton made his case succinctly: “Because a strong government was wanted during the late war, does it follow that we should now be obliged to accept of a dangerous one?” Civil liberties were not protected, he argued, and the document as written “would lead to the establishment of dangerous principles” endangering the rights of the states.

As in Virginia and Massachusetts, the New York convention demanded a bill of rights, and with the understanding that one would be added, the Constitution was ratified by five votes. In the end, Clinton reluctantly supported it, and the convention sent a circular letter to the other state legislatures calling for a second convention of all the states to address the need for constitutional amendments. This would ensure the “confidence and good-will of the body of the people.” One delegate submitted a motion for New York to secede from the Union should these amendments not be added in a timely manner. Clinton fervently supported the addition of a bill of rights and believed an amendment protecting state sovereignty essential.

As governor of New York,George Clinton was a pesky opponent of Federalists in the new central government and made a point of flaunting New York’s state sovereignty (for example by issuing his own “Neutrality Proclamation” after President Washington had done so at the federal level). Despite his “Neutrality Proclamation,” Clinton openly sympathized with the French in foreign affairs and befriended the infamous Citizen Edmund Genêt of France in 1793 after Genêt had irritated both Washington and Jefferson by incessantly attempting to garner American support for France’s war against England, Spain, the Netherlands, and the Holy Roman Empire. Genêt ended up marrying Clinton’s daughter a few years later. Clinton decided to retire in 1795, and in his farewell address stated that he hoped “for an union of sentiment throughout the nation, on the real principles of the constitution, and original intention of the revolution.”

Clinton returned to the governor’s seat in 1801 after being placed on the ballot to dissuade Vice President Aaron Burr from resigning his office and running for governor. No one trusted Burr, not even his old political allies, but he was still a force in New York politics. By nominating Clinton, the New York Republicans kept Burr off the ballot. But Clinton was ill, his wife had just died, and he considered another term an unbearable burden. He accepted the nomination only after continual prodding by his nephew and close friends; he was elected by a landslide.

Vice President Clinton

Jefferson andGeorge Clinton developed a warm relationship during the political struggles of the 1790s. Republicans viewed a Virginia-New York alliance as a necessary safeguard to their power at the federal level. When Burr created problems through his duplicity and his duel with Hamilton in 1803, he was dropped from the 1804 Republican ticket and replaced with Clinton. Clinton seemed a natural choice. He was a staunch Republican, a resolute defender of state’s rights, and had fought alongside Jefferson against the Federalists. In 1804, with the reelection of Thomas Jefferson, he became the fourth vice president of the United States.

His relationship with Jefferson, however, soon grew tense, particularly when Jefferson and Madison supported a trade embargo against all foreign commerce. Clinton denounced the move because trade was the lifeblood of New York’s economy. The people of New York sided with Clinton against Jefferson and Madison. Many prominent Virginians—like John Randolph, John Taylor, and James Monroe—agreed with Clinton and declared the embargo unconstitutional. This created an alliance between commercially minded republicans like Clinton and the agrarian “Quids” of the South.

With the 1808 election approaching, Madison appeared to be the frontrunner for the Republican nomination, but Randolph began floating a Monroe-Clinton ticket. The New York press called for an end to Virginian domination of the government, and Clinton harbored hope that he would be nominated as the presidential candidate. When it appeared that Madison would head the ticket, Clinton pressed his case more fervently.

The New York Republican press noted his record as a general and statesman and his policy of non-interference in “mercantile transactions,” while the Pennsylvania media championedGeorge Clinton’s Anti-Federalism and his opposition to Federalist corruption. When the votes were finally counted, Clinton received only six electoral votes (of New York’s 19 votes) for president, but easily secured the vice presidency.

As vice president for a second term, Clinton was openly hostile to Madison. He refused to attend Madison’s inauguration, and because of illness was often absent from the Senate. His most important action as vice president took place in 1811 when he cast the deciding vote against the re-charter of the Bank of the United States. He called the measure unconstitutional in a short speech and voted to break a 17–17 tie. This would be his last major public act. Clinton died in office on 20 April 1812 at the age of 72.

A states’ rights patriot

When pressed by Hamilton during the state ratification convention in 1788 over his theoretical hostility to strong government,George Clinton responded that he was “a friend to a strong and efficient government. But, sir, we may err in this extreme: we may erect a system that will destroy the liberties of the people.” Clinton, in fact, did favor strong government, but not at the federal level. His eighteen years as governor of New York were a model of fiscal restraint, but Clinton favored public activity at the state level for education, internal improvements, and the promotion of commerce, science, and industry. Yet, he only advanced this agenda when state revenue reached a surplus, and the state accomplished that without direct taxation. In fact, his nephew, Dewitt Clinton, was responsible for the Erie Canal, built by the state without federal money. Clinton was not a friend of federal spending or federal power, but he did not fear the effects of state government. Like most Anti-Federalists, he was not an anarchist. Government had a purpose, and next to local government, state government was the most effective and responsive level of authority. It preserved the traditions and customs of the people. This also illustrates another element of Clinton’s Anti-Federalism.

George Clinton realized that the North and South had social, political, and economic differences. He was a Northerner and he feared a government dominated by the South. In 1787 he asked if Southerners would “be as tenacious of the liberties and interests of the more northern states, where freedom, independence, industry, equality and frugality are natural to the climate and soil, as men who are your own citizens, legislating in your own state, under your inspection, and whose manners and fortunes bear a more equal resemblance to your own?” He aligned with Southerners when necessary, but at one time courted Northern Federalists because of their similar interests in commerce and industry. Clinton believed climate and geography would never allow the North and South to have similar interests.

Clinton has often been described as an ambitious political thug, but he thought of himself as another George Washington, the disinterested soldier who resigned his command rather than seize power. He was certainly ambitious, but Clinton often asked for retirement, and only reluctantly agreed to return to political life. When he retired, for the first time, in 1795, he expressed satisfaction that he was “done” with the job. In 1812, shortly after Clinton’s death, Elbert Herring delivered a eulogy that called Clinton a “hero,” a “patriot,” and a “father of his Country.”

George Clinton deserves a place among other Founding Fathers like Richard Henry Lee and Patrick Henry. He had served in the Revolution, was an effective wartime and peacetime governor who favored republican frugality, was a leader against consolidation and a champion of civil liberties, and was vice president twice. Such a record deserves attention—more attention than he usually receives in American history textbooks.

Cite This Article

"George Clinton: Founding Father, Vice President" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

July 24, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/founding-fathers-george-clinton-founding-father-vice-president>

More Citation Information.