George Armstrong Custer, always known as Armstrong or Autie to his friends (or Fanny to his West Point classmates, in honor of his girlish golden curls), was the North’s equivalent of Stuart. At West Point, he wasn’t much for studying but he loved to ride and was popular with his fellows for his love of fun and pranks (and racking up of demerits). His friends were mostly Southerners. He liked to read Southern chivalric romances. His family was ardently Democratic, loathing abolitionists, Whigs, and Republicans.

When Custer opted to fight for the Union (he had been born in and sent to West Point from Ohio and spent half his boyhood in Michigan), it was not to eradicate the Southern way of life. He admired it. Early in the war, he even attended, as best man, the wedding of a paroled Southern officer at a Virginia plantation. Then he hung around for nearly a fortnight courting one of the belles, until he realized that McClellan was evacuating from the Peninsula.

George Armstrong Custer did not fight for the Union because he disagreed with states’ rights. Nor did he fight because he wanted to abolish slavery (during the war he adopted one runaway slave as a servant). He fought for the Union because of the oath of allegiance to the United States he had taken at West Point. Throughout his life, Custer showed unstinting loyalty to his friends, devotion to his family, and gratitude to his benefactors. For all his carefree optimism, he never wanted to let any of them down. When he had earned some minor distinction at First Manassas, Custer rode into Washington, D.C., to introduce himself to Congressman John A. Bingham (a Republican) who had sponsored his nomination to the United States Military Academy. He thought it the right thing to do. The Congressman remembered the encounter:

Beautiful as Absalom with his yellow curls, he was out of breath, or had lost it in embarrassment. And he spoke with hesitation: “Mr. Bingham, I’ve been in my first battle. I tried hard to do my best. I felt I ought to report to you, for it’s through you I got to West Point. I’m. . . . ”

I took his hand. “I know, you’re my boy Custer!”

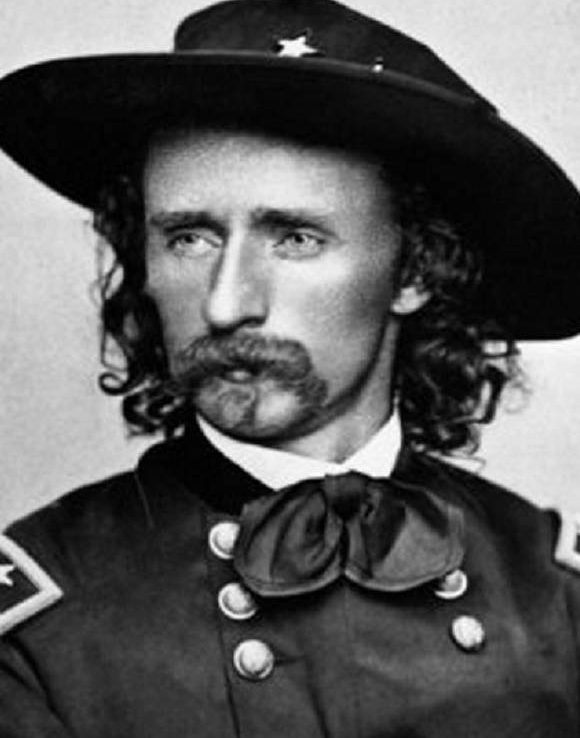

The Boy General George Armstrong Custer

Born a blacksmith’s son, he was without social distinction, but also without worries and with the luck of the Irish (though his heritage was German) for most of his life. He grew up in a large boisterous family where politics was meat and drink. But for George Armstrong Custer fun was ever the lure.

Like Stuart, he was a flirt, but unlike the Virginian, it is often supposed that he did not keep his affairs strictly within the confines of Christian propriety. He also liked a drink, though he later took the pledge—and, like Stuart, once on the wagon he never fell off. He was the most popular cadet at West Point because he was the most irrepressible, the king of demerits, and the sort who would ask the Spanish professor how to say, “Class dismissed,” en español, and when the poor sap said it, lead his fellow cadets out of the room. Unlike other cadets who found West Point a place of drudgery, Custer loved it, even as he violated its rules and absorbed all its punishments: “Everything is fine. It’s just the way I like it.” After his first year at the Point, he wrote: “I would not leave this place for any amount of money because I would rather have a good education and no money, than to have a fortune and be ignorant.”

The impish blacksmith’s son could resist no chance for a jape, avoided studying (he smuggled novels into class instead), but was nevertheless a bright lad, however sorry his grades. He graduated last in his class. Worse, or perhaps even better, he ended his West Point career court-martialed for failing to break up—indeed, for refereeing—a fight between two cadets. (Custer was not a brawler himself. His wit, which got him into so much trouble, also kept him out of fights, which he saved for the battlefield).

He graduated—or was court-martialed—straight from West Point to the front, serving at First Manassas and then on the Peninsula. Custer was fearlessly brave, a good scout (and considered a dispensable one, as he was sent up in balloons for aerial reconnaissance), leapt to the initiative in action, and took pride in never confessing to fatigue or hunger—all of which endeared him to his superior officers. It was after a successful reconnaissance that General McClellan, whom George Armstrong Custer greatly admired, turned to the young lieutenant and said, “Do you know, you’re just the young man I’ve been looking for, Mr. Custer. How would you like to come on my staff?” He did, and was given a brevet rank of captain.

Their regard for each other was mutual. McClellan said of George Armstrong Custer, “in these days Custer was simply a reckless, gallant boy, undeterred by fatigue, unconscious of fear; but his head always clear in danger and he always brought me clear and intelligible reports of what he saw when under the heaviest fire. I became much attached to him.”

After Lincoln dismissed McClellan, Custer joined the staff of General Alfred Pleasanton, and it was Pleasanton who really sent Custer’s star soaring by recommending the brevet captain for promotion to brigadier general—which promotion was endorsed by Washington, becoming official 29 June 1863—jumping him over captains, majors, and colonels. Custer was twenty-three, the youngest general in the Union army, and with characteristic flair he not only had stars sewn on his collar, but fancied himself up with a crimson tie, a broad-brimmed black hat, and a black velvet jacket that radiated gold braid. No matter that it made him a mark for enemy sharpshooters, George Armstrong Custer thought the men should be able to spot their general in the field. That, with his uniform and his distinctive goldilocks curls and blond moustache, they certainly could.

George Armstrong Custer in Command

George Armstrong Custer’s command was the second brigade of the third division of the Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Potomac, consisting of the First, Fifth, Sixth, and Seventh regiments of Michigan cavalry and a battery of artillery. These were the men he led into battle at Gettysburg with the cry: “Come on, you Wolverines!”

His first charge at Gettysburg, on 2 July 1863, was repulsed by Wade Hampton’s men. But Custer, whose horse was shot from beneath him, was cited for gallantry by his commander, Brigadier General Judson “Kill-Cavalry” Kilpatrick. On the next day, the day of Pickett’s charge, Kilpatrick’s men were ordered to shield the flank at Little Round Top. Custer, however, was detached to the command of General David McMurtrie Gregg whose men were in place to protect Meade’s rear from Jeb Stuart’s cavalry, the “Invincibles,” who had the same undefeated aura about them as did the infantry of Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia.

The fighting had already grown hot when George Armstrong Custer was given the orders he wanted, to lead a charge into the enemy. The honor fell to the 7th Michigan, Custer’s most inexperienced troops. The blue-coated cavalry charged into Confederate shot and shell and crashed into an intervening fence, which didn’t inhibit hand-to-hand fighting with sabers, pistols, and carbines between Virginians and Michiganders. The Federals were driven back but reformed themselves to meet a Confederate countercharge. Now at the head of the First Michigan, his best regiment, Custer thrust his sword in the air and shouted, “Come on, you Wolverines!” The clashing opponents collided with such fury that horses tumbled over each other—and this time, though the gun smoke, the point-blank discharges, and the clanging, bloodied sabers, it was the Confederates who pulled back. The invincible Virginians had been stopped. “I challenge the annals of warfare to produce a more brilliant or successful charge of cavalry,” wrote Custer in his official report. This wasn’t bragging—though Custer was often, wrongly, accused of that—it was boyish enthusiasm.

Indeed, the key to understanding George Armstrong Custer is that he pursued all his endeavors with boyish ardor, spirit, and pluck. He was tough, of course. He was proud of being able to endure any hardship. But he also thrived on action. He rejoiced in the field (and later on the Great Plains) surrounded by fast horses, good dogs (dogs recognized him as one of their natural masters), a variety of other animals (such as a pet field mouse), and an assortment of hangers-on, including, during the war, a runaway slave named Eliza who became his cook (she said she wanted to try “this freedom business”), a ragamuffin boy servant named Johnnie Cisco and another named Joseph Fought, who repeatedly deserted his own unit to be with George Armstrong Custer. Later in the war, Michigan troops petitioned en masse to serve under the golden-haired general.

George Armstrong Custer maneuvered friends and family onto his staff or into his units, including his brother Tom. And if it was cronyism it was cronyism that rewarded the brave, for all the Custers were gallant. His brother Tom won the Congressional Medal of Honor for his bravery at Saylor’s Creek (he was shot in the face, and survived to fight again).

A lot of people wanted to be with Custer. That included his bride, Elizabeth “Libbie” Bacon, whom Custer married in February 1864 after her father, Judge Daniel Bacon, could no longer keep the Boy General from his daughter. The George Armstrong Custers were the Bacon’s social inferiors, and Custer had a reputation as a ladies man. But, well, at least that ringleted fellow was a general, and not a blacksmith. And if Judge Bacon had strong doubts before the marriage, he should by rights have quickly buried them (though apparently he never did), for few couples in history seem to have been happier than Libbie and Armstrong. Indeed, his charming, well-bred, pious wife followed her vibrant enthusiast of a husband to camp whenever it was considered safe to do so. And on one occasion, after the war, while on the Great Plains, he was court-martialed and suspended from duty for a year, because he decided to swing by and visit his wife while on a campaign.

Jeb Stuart kept his wife away from camp, thinking it no place for a lady. George Armstrong Custer welcomed his wife, and thought Stuart’s flirtations with other women along the campaign trail was no behavior for a husband. But then again, Stuart employed his banjo players for evening entertainments of dancing and singing, and it seemed only right and proper to that cavalier that ladies be invited. Custer kept a band too—but he used it to for purely martial purposes: to inspire the men, to prepare a charge. There’s something admirable about the Custer way.

Phil Sheridan’s Golden Boy

In March 1864, George Armstrong Custer fell under the command of Phil Sheridan. Sheridan learned to like the cut of Custer’s jib—a man as eager to fight the enemy as he was. As an aide to General Meade noted, “fighting for fun is rare . . .[only] such men as . . .Custer and some others, attacked whenever they got a chance, and of their own accord.” And it gained him a reputation. When Libbie was introduced to President Lincoln in Washington, old Abe replied, “So this is the young woman whose husband goes into a charge with a whoop and a shout.”

George Armstrong Custer whooped and shouted his way through the Battle of the Wilderness, Trevilian Station, Yellow Tavern (where Stuart was struck down), the Shenandoah Valley, and the final campaign at Appomattox. Custer’s star rose ever higher, as he closed out the war a major general of volunteers and a brevet major general in the regular army. Not bad for a twentyfive-year-old.

George Armstrong Custer was a magnanimous victor. He liked the South and Southerners. Yes he had defeated them, and in his mind they deserved to be defeated, but he did not believe they should be abused and trampled upon simply because the Federal government now had the power to do so. He had his band play Dixie after he captured worn out grey troopers near the end of the war, and he became a political ally of President Andrew Johnson against the Radical Republicans. Already marked down as a McClellan man and a Democrat, Custer was winning himself political enemies.

But Sheridan was able to keep George Armstrong Custer gainfully employed, bringing him to Texas. That assignment, however, proved temporary, despite Sheridan’s best efforts. The War Department reduced Custer in rank to captain and assigned him to the 5th Cavalry. Custer wanted to find something better. Grant wrote a letter of recommendation for him to become a mercenary general in the Mexican army, but Custer’s application for leave was denied. Still, Custer hoped something would turn up—and it did, a lieutenant colonelcy in the 7th Cavalry, which at least had the promise of adventure, as the 7th was posted on the Great Plains.

Into the 7th Cavalry would come his brothers, Tom and Boston, a nephew, Autie Reed, and a brother-in-law, as well as such men as Captain Myles Keough, who had fought for the pope in Italy, Lieutenant Charles DeRudio, who had fought against the pope as an Italian nationalist, and Captain Louis Hamilton, the grandson of Alexander Hamilton. He was surrounded by friends, but also by a few enemies like Captain Frederick Benteen and Major Marcus Reno.

Sheridan took no nonsense from Indians, and he set George Armstrong Custer out to destroy any hostiles. Sheridan’s Indian policy was harsh, but to his mind, realistic: “The more we can kill this year, the less will have to be killed the next year for the more I see of these Indians the more I am convinced that they will all have to be killed or be maintained as a species of paupers.” Custer executed this policy—and he saw the barbarities that justified it: the child rapes and murders of abducted white girls by the Indians, the disemboweling of white boys, the perfidy of Indian promises (not so very different from the cliché of broken government promises to the Indians). And, like Sheridan, he saw the Indian Bureau as corrupt. Unlike Sheridan, he said so in ways that made him an enemy of General Grant, whose Indian policy was more conciliatory than was Sherman’s or Sheridan’s.

The romantic in George Armstrong Custer—and there was very little of anything else— relished living and fighting amongst the Indians. He was, if anything, sympathetic to their plight. He conceded that they were savage—and the New England pantywaists who called them noble savages had no idea what they were talking about—but he believed they could be civilized, Christianized, and he repudiated any talk of exterminating the Indians. He went further, stating, “If I were an Indian, I often think that I would greatly prefer to cast my lot among those of my people who adhered to the free open plains, rather than to submit to the confined limits of a reservation, there to be the recipient of the blessed benefits of civilization, with its vices thrown in without stint or measure.” The modern stereotype of Custer as a crazed Indian-killer is a coarse, blatant slander. The old image, of Custer as a hero, is a simple truth (and one enunciated by former Confederates, like Joseph E. Johnston).

The Battle of the Little Big Horn, George Armstrong Custer’s Last Stand, is the crown of thorns of the Custer legend. What actually happened at the battle must also be, in some measure, a matter of mystery and conjecture. But one thing can be said with certainty: the dash and bravery, the willingness to take risks, his belief that disciplined cavalry could defeat Indian numbers greater than their own, all of which had served him so well in the past, deserted him here. It is very likely that the image of Custer being among the last to die, if not the very last to fall on what is now George Armstrong Custer’s Hill, is a true one. And with his death, as the journalist foretold, a paragon of a “bright and joyous chivalry” passed from the earth.

Would you like to learn the complete history of the Civil War? Click here for our podcast series Key Battles of the Civil War

Would you like to learn the complete history of the Civil War? Click here for our podcast series Key Battles of the Civil War

Cite This Article

"General George Armstrong Custer (1839-1876)" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

July 27, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/general-george-armstrong-custer-1839-1876>

More Citation Information.