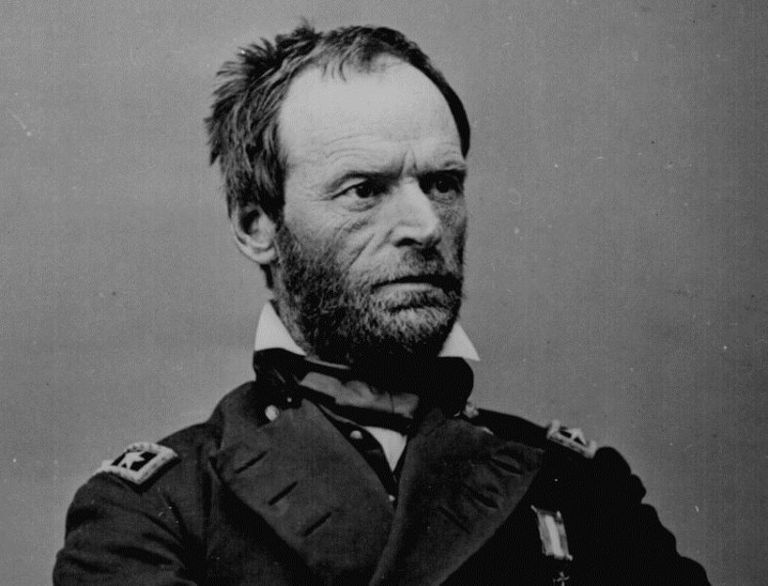

The popular image of William Tecumseh Sherman is of a roughhewn, high-strung (to the point of insanity), ravager of the South. The image is reinforced by photographs of the Federal general. His hair is often unkempt, his look stern, and his countenance apparently reflecting an ill-tempered mind. But the Sherman of reality was a man who loved dancing and parties, was popular with the ladies, and was brutally honest, selfless, and devoted to his duty. He loathed the politicians (his brother was one) who had brought the country to war, despised abolitionists (again, his brother qualified), and embarked on his savage march through Georgia because of his conviction—founded on his own experience in the South—that it was the only way to break such a determined people. One might consider that a compliment. William Tecumseh Sherman, however, did not mean it so. As one of his most famous biographers (and admirers) put it in 1929, William Tecumseh Sherman believed in the survival of the fittest. The South was not economically fit, and he was in favor of dealing with that unfitness by the “economic sterilization” of the South to the point of driving Southerners from their homes and replacing them with efficient, industrious Northerners. Sherman was the perfect exemplar of the blunt utilitarianism of the North.

William Tecumseh Sherman’s “religion”

William Tecumseh Sherman came from distinguished stock. His father had served on the Ohio supreme court, his grandfather had been a judge, and he was related to Roger Sherman who signed the Declaration of Independence. Sherman, however, was orphaned at the age of nine and taken in by the family of Thomas Ewing, a United States senator, whose daughter Sherman eventually married (President Zachary Taylor and his cabinet attended the wedding). His foster parents were devout Catholics and insisted on Sherman being baptized (which Sherman’s Episcopalian/Presbyterian parents had neglected). So it was a priest who gave him the name William, for which Sherman had little use (just as he later had little use for religion). His friends called him “Cump,” a shortening of Tecumseh, the name his father gave him in admiration of the famous Indian chieftain.

Though not a churchgoer himself, Sherman allowed his children to be raised as Catholics. He was nevertheless appalled when one of his sons became a Jesuit priest (the priest who would, in fact, preside at Sherman’s funeral Mass). Sherman’s religious beliefs seem to have traveled from being “not scrupulous in matters of religion” to eventually lodging himself where such people go: in the ranks of the deists. Religious doctrines were not for him, any more than were Southern constitutional doctrines about states’ rights. There was, instead, in the practical Northern mind of Sherman, and in that of many of his Union colleagues, a belief in a certain sort of natural law—not the natural law of the Catholic Church, but the natural law of Thucydides who said that the powerful do what they will, and the weak suffer what they must. Or, to put it in the words of one of Sherman’s later admirers, the military theorist Basil Liddell-Hart, Sherman’s moral compass was a Unionist reading of the United States Constitution, which held that “law, like all law in a democracy, was founded on the natural law that might is right.”

William Tecumseh Sherman: The young soldier

He was sent to West Point, which he hated—neatness not being a word one associates with Sherman. Still, if he failed on inspections, he made up for it in his studies, graduating sixth in his class. As events would prove, he was a well-educated soldier, however disheveled his appearance.

He was sent to Florida to fight the Seminoles—a project in which he took a healthy enjoyment. “These excursions,” he wrote, “possessed to us a peculiar charm, for the fragrance of the air, the abundance of game and fish, and just enough of adventure, gave to life a relish.” If only we could all have a period of Indian-fighting.

In Florida he earned quick (which was rare) promotion, which led in due course to his transfer to Charleston, South Carolina. He found he much preferred fighting Indians to the social life of the gallant South. But when the next war came along, with Mexico, he missed it, through sheer bad luck. He tried mightily to get in on the action, but was first diverted to recruiting duties, and when he finally received orders to sail to California with the Third Artillery, he arrived just in time for that theatre of the war to have drawn its curtains. But he was appointed acting adjutantgeneral to Colonel Richard Barnes Mason, the acting military governor of California. (Mason, a son of Lexington, Virginia, lent his name to the now decommissioned Fort Mason in San Francisco.) William Tecumseh Sherman gained a taste for military government, of which he approved: “military law is supreme here and the way we ride down the few lawyers who have ventured to come here is curious . . . yet a more quiet community could not exist.” But he kicked against the fate that kept him in quiet California while his brother officers were gaining fame amidst the roaring artillery, the crackling musketry, and the sabre strokes of battle.

William Tecumseh Sherman was seething with self-contempt for having missed his chance: “I really feel ashamed to wear epaulettes after having passed through a war without smelling gun-powder.” But General Persifor Frazer Smith, incoming commander of the newly created Department of the Pacific had other ideas for young Sherman, requiring him to stay on as his adjutant-general. From this Sherman graduated to commissariat duty, with assignments in St. Louis and New Orleans.

Since the possibility of war now appeared remote, Sherman, at the age of thirty-three, and with a growing family to support, surrendered his commission and accepted an invitation offered by a friend to return to California as a banker. He had an acute business mind, a steady nerve (necessary in the California bank crisis he had to endure), and an unimpeachable honesty that set him apart from some of his bank’s competitors.

Despite his own virtues as a banker, his business career careened from failure to failure. In 1857, Sherman’s bank moved from vigilante-governed and economically depressed California to New York, where the credit institutions quickly took a dive. William Tecumseh Sherman dutifully made sure his depositors were taken care of (though his personal accounts suffered), and then decided it was time to try his hand at some securer field. He became a lawyer, joining with two of his brothers-in-law, and working largely on keeping the books and surveying property (which tapped some of his military topographical skills).

Yearning to get back in uniform, he eventually ended up as superintendent of a startup military academy in Louisiana (what is now Louisiana State University). Sherman proved himself a resourceful, popular, and effective administrator of the new school, even if it took a while for young Southern gentlemen, used to giving orders rather than taking them, to bend to the discipline. These were the men—the “young bloods,” the hard-riding, liberty-loving, young Southern aristocrats—of whom, during the war, when he saw them in the Confederate cavalry, Sherman would say, “War suits them, and the rascals are fine, brave riders, bold to rashness and dangerous subjects in every sense.”

Sherman had always despised abolitionists, whom he thought ignorant idealists, rabble-rousers driving the country to war. But he was equally contemptuous of Southern fire-eaters, of the sort who now surrounded him, who spoke pridefully of secession and Southern independence, and deprecated the danger of war. As for Southern unionists, he scoffed at how easily they allowed themselves to be intimidated.

William Tecumseh Sherman was, if nothing else, a forthright and honest man and he never altered his own strongly anti-secession views to suit his employers, the cadets, or their families; and it is a tribute to him and to the gentlefolk of the South that he was tolerated and respected as a pro-Union man.

When Louisiana withdrew from the Union, the governor of the state, who had officially appointed Sherman to his position, did not ask for him to resign. Indeed, the administration was keen to keep him on, but Sherman would have no part of it. He tendered his resignation, moved to St. Louis, became president of a streetcar company, and then in May 1861, one month after General Beauregard—a former colleague and friend of Sherman’s—fired on Fort Sumter, he accepted a commission to fight for the Union.

William Tecumseh Sherman: Free trade equals war, and so does Democracy

William Tecumseh Sherman did not see the abolition of slavery as an appropriate Union war aim. When his brother John Sherman—who won the unflattering political nickname “the Ohio Icicle”—was elected to Congress in 1854 (as a Republican, a member of the newly formed anti-slavery party), Sherman wrote to him, saying: “Having lived a good deal in the South, I think I know practically more of slavery than you do . . . .There are certain lands in the South that cannot be inhabited in the summer by whites, and yet the negro thrives in it—this I know. Negroes free won’t work tasks of course, and rice, sugar, and certain kinds of cotton cannot be produced except by forced negro labour. Slavery being a fact is chargeable on the past, it cannot, by our system, be abolished except by force and consequent breaking up of our present government.” His counsel, then, was to leave the South alone, for the North to use its increasing political predominance prudently, to trust that Missouri and Kentucky would eventually, of their own volition, abolish slavery, and that the other states of the South would in due course follow as they watched the rapid-growing prosperity of the North compared to the South’s own economic stasis.

But war having now come, he believed that “the question of the national integrity and slavery should be kept distinct, for otherwise it will become a war of extermination—a war without end.” He did not want to spend the rest of his life trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored. Indeed, he wished the war had never come and said that he would “recoil from a war, when the negro is the only question.”

In William Tecumseh Sherman’s mind the idea of simply letting the South go—without binding it to the Union by armed force—was an impossibility, because free trade (such as the Southern Confederacy professed) meant war. The North relied on money from tariffs, so “even if the Southern States be allowed to depart in peace, the first question will be revenue. Now if the South have free trade, how can you collect revenues in eastern cities. Freight from New Orleans to St. Louis, Chicago, Louisville, Cincinnati, and even Pittsburgh, would be about the same as by rail from New York, and importers at New Orleans, having no duties to pay, would undersell the East if they had to pay duties. Therefore, if the South make good their confederation and their plan, the Northern Confederacy must do likewise or blockade. Then comes the question of foreign nations. So, look on it in any view, I see no result but war and consequent change in the form of government.”

It was a war that he thought could last thirty years, with casualties in the hundreds of thousands. Beside the economic issue, which made war inevitable, William Tecumseh Sherman saw as the great crusade not the “side issues of niggers, state rights, conciliation, outrages, cruelty, barbarity, bankruptcy, subjugations, etc.,” which were all “idle and nonsensical” but for the preservation of the Federal union in such a way that would forever destroy the power of the separate states, those “ridiculous pretences of government, liable to explode at the call of any mob,” and put an end to the “the tendency to anarchy. . . .I have seen it all over America, and our only hope is Uncle Sam.”

For Sherman, loyalty to the Federal government, the Constitution, and the Union meant crushing the democratic spirit of such as Southerners who thought they had a right to determine their own form of government, their own confederation. As Sherman wrote to his brother, “A government resting on the caprice of the people is too unstable to last . . . .[A]ll must obey. Government, that is, the executive, having no discretion but to execute the law must be to that extent despotic.” So Sherman did not fight to free the slaves (whom he thought freed and armed would become another tribe, or tribes, of marauding Indians); he did not fight for a Constitution that envisioned a limited Federal government with real sovereignty lying with the states; nor by any stretch did he fight for democracy. He explicitly fought against it. “We have for years been drifting towards an unadulterated democracy or demagogism. Therefore our government should become a machine, self-regulating, independent of the man.”

William Tecumseh Sherman, then, fought for order; ideally perhaps for martial law as the proper government model, which would ensure that government was run like a self-regulating machine where “popular opinion” would not interfere with the execution of the “law.” Certainly in California he saw martial law as preferable to its apparent alternative, vigilantism, and it seems that he came to apply that prescription to the nation as a whole. And this being the case, it is not hard to understand why he came to desire the exaction of a Carthaginian peace upon the proud, aristocratic, and libertyloving South.

Early campaigns

William Tecumseh Sherman returned to the colors as a colonel. He fought at First Manassas, receiving minor wounds to his knee and shoulder, but felt thoroughly disgraced by the way his troops and the rest of the Federal army were routed. He blamed the defeat on having to lead an army of volunteers who “brag but don’t perform” and did whatever they pleased. “I doubt,” he wrote, “if our Democratic form of government admits of that organization and discipline without which an army is a mob.” And “a mob,” he thought, was a precise description of the men he led: “No curse could be greater than an invasion by a volunteer army. No Goths or Vandals ever had less respect for the lives and property of friends and foes, and henceforth we ought never to hope for any friends in Virginia.” Luckily, “Our adversaries have the weakness of slavery in their midst to offset our democracy,” he said, “and it’s beyond human wisdom to say which is the greater evil.”

Still, depressing as First Manassas had been, Sherman emerged from the scrap promoted to brigadier general. William Tecumseh Sherman was, of course, pleased by his promotion and devoted to his duty, but also interested in keeping a low-profile at the outset of the war, for he expected not only a long and costly war, but a war full of early reverses, which would lead the mob to demand the heads of generals. He wanted to emerge after the politicians had bollixed things up and the fickle public had executed its scapegoats.

Lest Sherman be regarded as having overly saturnine views, it should be remembered that he was serving in close proximity to Washington, and the sight of the elected government in action did not breed confidence. Nor was there much good to be found in volunteer regiments, which conducted sit-down strikes—mutiny, in military terms—refusing to take orders or form ranks, and insisting that their short-term enlistments were up. William Tecumseh Sherman retained his confidence in the regular army; it was the rest of the country about which he had doubts.

He was sent to Kentucky, a vital border state of divided loyalties and the birth place of the presidents of both the Union and the Confederacy. William Tecumseh Sherman welcomed the new assignment. He considered himself a man of the West, thought the vital point in the war was control of the Mississippi River, and that the lynchpin that could hold and restore the Union, or without which it would disintegrate, was Kentucky. Not long after he arrived General Robert Anderson, a native Kentuckian, and like Sherman a pro-slavery Unionist, asked that Sherman replace him as commander of the Department of the Cumberland, (Anderson, the hero of Fort Sumter, felt obliged to retire because of ill health). Sherman was duly appointed. He had emerged, perhaps sooner than he hoped, to a leading position in the war.

William Tecumseh Sherman thought the situation in Kentucky was dire. His assessment that he needed 200,000 more men, his wildly inflated view of the number of Confederates confronting him, his frustration at the lack of weapons and supplies, his contempt for the volunteer regiments at his disposal, and his worry that the Federals were surrounded by Confederate sympathizers, all kept him in a constant state of active turmoil that left little time for rest or meals, to the point where he seemed overwhelmed by his duties and some doubted his sanity. Was Sherman a gloomy, ill-tempered martinet—a gruff professional whose pessimism reflected a military reality beyond the grasp of amateur officers and ignorant politicians—or was he insane? That Sherman felt the burden of command was obvious—he asked McClellan to relieve him, and McClellan obliged, sending General Don Carlos Buell to take his place.

William Tecumseh Sherman was then assigned to Missouri, under the command of General Henry Halleck, who quickly became concerned about Sherman’s alarums about a presumed Confederate threat—so concerned that he had a doctor examine Sherman. The doctor declared him of “such nervousness that he was unfit for command,” which corresponded with Halleck’s own opinion. Halleck, who was well disposed to Sherman, sent him on three-week’s leave to recover himself.

Sherman’s recovery was speeded by an article he read in the Cincinnati Commercial. It carried the quaint headline: “Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman Insane” and was quickly picked up and discussed in newspapers across the country. Its chief evidence was that Sherman had frequently been panicked and grossly exaggerated the dangers posed by the Confederate forces in Kentucky and Missouri.

But if misconstruing the size of the enemy is a sign of insanity, General George B. McClellan, commander of all the Union forces, was as insane as anyone. McClellan, however, had the advantage of a polished manner and a hauteur that rested on his reputation for excellence (though he too would give way to panicked messages in action).

William Tecumseh Sherman detested reporters, had a harsh and abrasive manner, and could indeed be impulsive in his orders. This was both Sherman’s gift and his flaw. His mind, for all its claims to hard practicality, was intuitive. One of his professors in Louisiana said of Sherman that “his mind went like lightning to his conclusions, and he had the utmost faith in his inspirations and convictions.” Sherman once told him, “Never give reasons for what you think or do until you must. Maybe, after a while, a better reason will pop into your head.” This revealing comment of William Tecumseh Sherman’s, was, of course, to one way of thinking, the height of practicality. Reasoning after all was too abstract, too Thomistic perhaps, to be the chief tool of the practical man. Better by far to provide rationalizations after the fact.

Recovery in battle

William Tecumseh Sherman’s first assignment was a quiet one, training troops, but he yearned for an opportunity to reclaim his reputation, and Halleck looked to give him his chance, eventually sending him up the Tennessee River to engage the enemy. His early attempts to strike a reputation-recovering blow fizzled. But fate was awaiting him and his troops at Pittsburgh Landing. Serving now under General Grant, Sherman established his headquarters at the Shiloh Methodist Meeting House. Sherman’s men took the brunt of the Confederate assault, and the general who had been turfed out on leave for a nervous breakdown now showed himself a capable commander under fire. He was wounded through the hand, which he wrapped up himself while leading his troops on horseback. Several horses were shot and killed beneath him, as was one of his aides riding alongside him. But Sherman kept his command presence.

The great controversy of Sherman’s part in the battle of Shiloh is whether the Confederates had caught him napping. William Tecumseh Sherman denied it, pointing out that Federals and rebels had been skirmishing for days before—and if nothing else, Sherman was an honest man. Still, it appears the Confederates had the jump on him.

But William Tecumseh Sherman’s troops held up better than other Union troops, who turned tail and fled (they certainly seemed surprised), and many journalists this time found Grant a more inviting target for criticism. Sherman hated journalists, regarded them as the nearest thing to traitors (because they betrayed important information to the enemy), and held them within the same contempt that he held democracy. Journalists could never tell the truth about the cowardly, indisciplined mob of volunteer soldiers in blue; in a democracy, Sherman reflected bitterly, ignorant and malicious reporters flattered the rabble at the expense of the professionals who knew what they were doing. William Tecumseh Sherman, however, felt no such restraint on his truth-telling. He sought out units that he thought had performed poorly and gave them detailed tongue-lashings about their shortcomings; and he cooperated with Grant in weeding out officers who had failed. But for Sherman personally, the greatest result of Shiloh was that he had been engaged in the biggest battle in American history. He had handled himself creditably, and after the initial shock of battle, his men had mounted a stubborn defense that turned into a counterattack and drove the rebels from the field.

Military governor of Memphis

On 20 July 1862 Sherman took over the occupation of Memphis. He kept his troops busy—he didn’t want them getting fat and lazy in barracks. William Tecumseh Sherman told the people, according to a newspaper reporter, that “he thought Memphis was a conquered city. . . .He had not heard that there had been any terms at the capitulation.” His army, he added, “didn’t come here to visit their friends. The people of the city were prisoners of war. They may be Union, and they may not. He knew nothing about that. One thing was certain: they had not fought for the Union so far as he had heard . . . .He had nothing to do with social, moral, or political questions; he was a soldier and obeyed orders and expected his orders to be obeyed.”

So far, so William Tecumseh Sherman, but in fact he relaxed the previous strict administration of the city, granting the people considerably more freedom of movement, returned to them the right to buy and consume alcohol, deprecated Northern speculators and merchants who came to the city and put trade before the war effort, and tried to crack down on Federal soldiers who were disgracing their cause by pillaging civilians.William Tecumseh Sherman confessed in a letter to one of his daughters that “I feel that we are fighting our own people, many of whom I knew in earlier years.”

William Tecumseh Sherman’s brother John, now a United States senator, advocated that Confederates be treated “as bitter enemies to be subdued—conquered— by confiscation—by the employment of their slaves—by terror. . .rather than by conciliation.” Sherman, at this point, thought differently, and especially disagreed with his brother’s abolitionist sentiments. He wrote his brother telling him that he was “wrong in saying that Negroes are free & entitled to be treated accordingly by simple declaration of Congress. . . . Not one Nigger in ten wants to run off. There are 25,000 in 20 miles of Memphis—All could escape & receive protection here, but we have only about 2,000 of whom about half are hanging about camps as officers servants.” He believed that freeing slaves was pointless unless alternative work was provided for them—and if it had been up to him, he made clear, slavery would not be disturbed.

Vicksburg

After four months of governing Memphis according to “the law,” which was actually his whim—and all the better for it—William Tecumseh Sherman gained an assignment that he could relish: he would be joining Grant on the campaign to take Vicksburg, the “Gibraltar of the South.” In this campaign Sherman showed less interest in conciliating the enemy. His troops traveled by boat down the Mississippi. Sherman gave orders that if the boats took fire from the shoreline, the troops were to disembark and lay waste the nearest town in retaliation. If any journalists found their way on board his boats, they were to be conscripted immediately or arrested as spies. But Sherman’s first attempt at the Southern citadel was admirably summarized in his Caesarean official report: “I reached Vicksburg at the time appointed, landed, assaulted, and failed.”

He failed again in his attempt to take the Confederate defenses at Chickasaw Bluffs in a landward assault. He had attempted this after overruling Admiral David Porter’s proposal of a joint naval-army attack on Haynes’ Bluff. Fighting in difficult, swampy terrain, Sherman’s men attributed their failures to more than bad luck, there were rumors again about Sherman’s sanity, and even Admiral Porter, who got on well with Sherman, thought the general was a burnt-out case—a commander who shared too many of the physical hardships of the men. These, combined with the already arduous physical, mental, and emotional strains of command, had broken him down. Porter helped buck up Sherman’s spirits by telling him that the loss of 1,700 men at Chickasaw Bluffs was as nothing in a war like this. Such minimizing of the butcher’s bill seemed to cheer Sherman immensely.

Serving now under John A. McClernand, a politician appointed as a general, whom Sherman despised as a vainglorious idiot (Admiral Porter seconded that view), the Federal troops withdrew for easier pickings, starting with Fort Hindman on the Arkansas River. Though Fort Hindman fell to Union hands, it was a minor engagement and Sherman had to share the credit (though he was loath to do so) with McClernand. That in itself was, as McClernand put it, more “gall and wormwood to the clique of West Pointers.”

William Tecumseh Sherman took out his gall and wormwood by calling for the execution of a reporter who had criticized him and by ferreting out how officers who didn’t like him (like McClernand) were using the press to play up their own achievements while disparaging his. Things improved when Sherman became a corps commander under Grant. Though Sherman thought Grant had let him down in not supporting his assault on Vicksburg, Grant was a man he respected and liked: the two Ohioans trusted each other and mistrusted the press and self-promoting officers like McClernand.

In Grant’s conquest of Vicksburg, Sherman played a supporting role, preventing Joseph E. Johnston from relieving the besieged Southern fortress, and then occupying Mississippi’s capital of Jackson, after Johnston retreated from it. At Grant’s request, Sherman was promoted from a brigadier general of volunteers to a brigadier general in the regular army. When Grant became commander of the Military Division of the Mississippi he rewarded Sherman with command of the Army of the Tennessee. William Tecumseh Sherman’s first assignment was to join the Federal breakout from Chattanooga; and here his preparations came in for as much criticism for slowness and delay as were usually leveled at General Thomas (though Sherman had the added burden of grieving over the death of his favorite son, Willie, who had contracted a deadly fever while visiting his father in Mississippi). When Sherman sent his troops against the Confederate right at Missionary Ridge, they were stymied; it was Thomas’s men who eventually swept the rebels off the high ground. But Grant gave Sherman credit for tying down the Confederate right and guaranteeing Thomas’s success.

The following year, 1864, was the year that would truly make William Tecumseh Sherman’s name. It was also the year he finally gave up trying to enforce his previously strict opposition to pillaging and plunder. It was a utilitarian decision driven in part by his noticing that when the Federal army lived off the land (that is, Southern farmers) it effectively stripped that area of provisions for the enemy. The idea formed in Sherman’s mind of creating a “belt of devastation.” The South, he reckoned was united against the Union, and every Southern male was a potential guerilla, such as fired on Federal boats, harassed Federal supply lines, or broke up Federal rails. While Sherman respected most Confederate commanders, especially those who were fellow West Pointers, he had no truck with guerilla leaders and believed them simply outlaws—outlaws supported by Southern civilians, who were therefore accessories to their crimes.

William Tecumseh Sherman also declared, as a matter of law, that “by rebelling against the only earthly power that insured them the possession of such property”—the United States government—Southerners had lost their right to own slaves, and “ex necessitate the United States succeeds by act of war to the former lost title of the master.” So William Tecumseh Sherman’s legal training was put to good use, apparently.

When Lincoln promoted Grant to command of all Federal armies, Grant appointed Sherman as his successor to the Military Division of the Mississippi. Grant would take on Lee in the East, and Sherman would face Joseph E. Johnston in the West, with the objective of seizing Atlanta. The outcome of Sherman v. Johnston was inevitable: Johnston was outnumbered, entrenched, was outmaneuvered, and retreated. Johnston’s entire career in the war rested on brilliant tactical retreats. The one time William Tecumseh Sherman assaulted Johnston directly, at Kennesaw Mountain, it was another defeat for Sherman, though he brushed if off with Admiral Porter’s earlier rationalization that losses were as nothing in this war. Or, in Sherman’s own words, “I begin to regard the death and mangling of a couple of thousand men as a small affair, a kind of morning dash—and it may be well that we become so hardened.” Compare this to Lee’s famous line that “It is well that war is so terrible—we should grow too fond of it.”

The gallant Confederate General John Bell Hood replaced Joseph E. Johnston and if his tactics were different—frenzied, hopeless assaults rather than clever retreats—the results were the same. Atlanta fell into Sherman’s hands, and the conqueror of the city promptly, on 5 September 1864, ordered expelled its entire civilian population. Sherman had not innovated this strategy. Grant was already trying to drive Virginians out of the Shenandoah Valley; and in Missouri, some 20,000 suspected Confederates had been driven from their homes (which were burned). To William Tecumseh Sherman it was another matter of practicality: the city was on his supply lines and he was not about to take on the responsibility of feeding Southern civilians. In the North, Sherman was now a hero.

He was also the ultimate military commander of a region stretching from the Mississippi River to the Appalachian Mountains. He had a plan, of which Secretary of War Edwin Stanton approved, of expelling Confederates outside the United States (any location would do, though among his suggestions were Madagascar and French Guiana). This was preliminary to his grander scheme of repopulating the South with Northerners: “The whole population of Iowa & Wisconsin,” he wrote his brother the senator, “should be transferred at once to west Kentucky, Tennessee & Mississippi.” Though like many grand schemes, this bore little fruit at first. The repopulating of the South had to wait for the great rust belt migrations of the last quarter of the twentieth century.

Meanwhile, Hood’s army still existed and was looking for a fight. Sherman was content to leave that fighting to Thomas. His great plan was for a march to the sea in which he could wreak a path of destruction on the South, destroying railroads, burning cities, and of course eating any comestible in sight. The idea of restraining the destruction of civilian property was gone with the wind—William Tecumseh Sherman’s men even burned houses as a signaling system between units—and his attitude to such destruction had come to resemble his attitude to casualties: che sera sera. It couldn’t be helped, and in any event the South needed to be taught a lesson. Certainly there were orders limiting the wreckage (and William Tecumseh Sherman could be kindly when his personal attention was engaged), but these orders were more honored in the breach than in the observance. When justice was meted out, it could be delivered as roughly to soldiers as civilians. During the burning of Columbia, South Carolina, Federal officers simply shot out of hand riotous drunken soldiers in blue.

Such forces as the Confederacy had were largely arrayed on the South’s northern borders. For all his fuming about “partisans,” William Tecumseh Sherman met with little resistance as his army burned its way through Georgia and the Carolinas, the only battle of consequence being Bentonville, on 19–21 March 1865, when Joseph E. Johnston made his last stand in North Carolina before the end of the war. Besides that, and the occasional skirmish with Joe Wheeler’s Confederate cavalry, Sherman’s march was not a running battle, but the plowing of a desolate trench that obliterated (with a few exceptions, like the city of Savannah) anything in its way.

When the end was finally near, Sherman wrote his wife that Jefferson Davis and “at least 100,000 men in the South must die or be banished before we can think of peace. I know them like a book. They can’t help it any more than the Indians can their wild nature.” Since cutting his swath through the South, Sherman had won an avalanche of Northern accolades, and it clearly went to his head. When he met with Joseph E. Johnston to discuss an armistice (the duo later joined by Confederate General and Secretary of War John C. Breckinridge), Johnston convinced Sherman to go beyond the terms Grant had offered Lee in order to achieve a general peace. Sherman seized the opportunity, thinking that by it he could tamp down any possible remaining Southern insurrections and guarantee “peace from the Potomac to the Rio Grande.”

Though Sherman counseled Breckinridge to leave the country, the terms agreed were remarkably lenient, leaving the South’s state governments intact (where pro-Union and pro-Confederate governments jostled for recognition in the same state, the Supreme Court would decide). Confederate troops, in order to maintain civil order, would retain their arms until they reached their state capitals. In exchange for pledges of loyalty to the Union, a general amnesty and all Constitutional rights would be granted to Southern citizens, including property rights. The terms were forwarded to Washington for President Andrew Johnson’s approval. Instead of plaudits, Sherman was showered with abuse and subject to accusations of treachery and insanity (again) by the press. General Grant came to see Sherman, breaking the news of the disaster and telling him that his agreement with Lee had to be the model for Sherman’s agreement with Johnston, and so it was done.

After the war, William Tecumseh Sherman was made a lieutenant general and given command of the Military Division of the Missouri, a region that stretched from New Mexico north to Montana, east across the Dakotas through Minnesota and as far south as Arkansas and Oklahoma. He made his home in St. Louis, where he’d lived before, and maintained an active social schedule, without his wife whom he considered suitable for raising his children and listening to his complaints but little else. As for his work, he disdained the southwestern territories under his command (as well as Texas, which was not) and thought they should be returned to Mexico as wasteland. He had a certain sympathy for the Indians, thinking, at times, that he would have liked to have been one—his wife agreed with him; she thought he might be more at home with a squaw than a white woman—while regarding them as a primitive race that, realistically, did not have much of a future. They either had to be tamed and kept on their reservations or exterminated.

As for the South, he returned to his prewar views that the region should be left alone and not be goaded, trampled upon, and reconstructed by Radical Republicans. He opposed giving voting rights to blacks, supported the idea of segregation (and enacted it when he occupied Savannah during the war), and preferred that political power in the South be returned to the planter and professional classes, the only ones capable of wielding it intelligently.

With Grant’s election as president in 1868, Sherman was promoted to full general and became commander of the entire United States Army. It meant moving from St. Louis to Washington, a transfer he did not relish, and in 1874 he managed, with Grant’s approval, to become a telecommuter, working out of St. Louis and relying on the telegraph lines to keep him in touch with Washington. Sherman always loathed everything about politics—something that, as a soldier, he thought he was above—and his sense of honor did not allow him to do the sort of lobbying, currying favor, and politicking that Washington’s ways required. He did, however, return to Washington in 1876.

William Tecumseh Sherman’s vision was for a large professional army. Congress’s was for a small frontier force supplemented by militia. Congress won. He had more successful influence over West Point where, while he was a jealous guardian of tradition, he oversaw the transformation of the academy from a de facto school for engineers to a school truly for soldiers. He was also not a traditionalist when it came to uniforms and weaponry, where he was always on the side of practicality and firepower.

On 8 February 1884, William Tecumseh Sherman retired, and famously repudiated any talk that he might run for president: “I will not accept if nominated and will not serve if elected.” He returned to St. Louis, and in 1891 he died, repeating what he had prepared to be his last words: “Faithful and honorable. Faithful and honorable.” By his own lights, he was.

Would you like to learn the complete history of the Civil War? Click here for our podcast series Key Battles of the Civil War

Cite This Article

"General William Tecumseh Sherman (1820-1891)" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

July 27, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/general-william-tecumseh-sherman-1820-1891>

More Citation Information.