Grant’s War Strategy: General Military Skills

Aggressiveness

Between Robert E. Lee and Ulysses S. Grant, both generals were quite aggressive. Grant’s aggressiveness was consistent with the North’s superior manpower and its need to proactively win the war, while Lee’s was inconsistent with the South’s inferior manpower and its need only for a deadlock. In short, Grant’s war strategy, aggressiveness won the war while Lee’s lost it. General Fuller encapsulated the contrary effects of the two generals’ aggressiveness: “ . . . the fact remains that Grant’s pugnacity fitted the general strategical situation—the conquest of the South, whilst Lee’s audacity more than once accelerated rather than retarded this object.” Ironically, the Overland Campaign of 1864, for which Grant’s war strategy is criticized as taking too many casualties, demonstrate s what Lee could have done had he stayed on the strategic and tactical defensive throughout the war. As historian Alan Nolan concluded, “The truth is that in 1864, Lee himself demonstrated the alternative to his earlier offensive strategy and tactics.”

Lee was too aggressive. With one-quarter the manpower resource s of his adversary, Lee exposed his forces to unnecessary risks and ultimately lost the gamble. The gamble was unwarranted because Lee only needed to play for a tie; instead, he made the fatal mistake of going for the win. Lee failed to accept the reality that the North had to conquer the South; instead, he tried to conquer the North—or at least destroy its eastern army. Military historian Russell Weigley blamed Lee’s stubbornness for Gaines’ Mill, Malvern Hill, the mistaken Maryland Campaign, and his risking his entire army by fighting at Antietam. Bevin Alexander compared Lee unfavorably to Jackson on the issue of over aggressiveness: “Jackson was a military genius. He had found a way to avoid making frontal assaults against the massed power of the Union Army. This was the essence of his intellectual breakthrough. But Lee had not absorbed the lesson. And this sealed the fate of the Confederacy.”

Many have argued that Lee had no choice but to be recklessly aggressive because the South had no other way to win the war. Among them was Joseph L. Harsh, who contended that Lee hoped to destroy the Northern will to fight by going on the offensive and thus causing high Northern casualties and destroying its will to continue a long, costly war. Others have argued that Lee’s aggressiveness was compelled by Southerners’ expectations that he take the offensive. Ironically, Lee’s aggressiveness caused high, intolerable Southern casualties and played a major role in the decline of Southern morale and willingness to continue the war. As Alan Nolan argued, because the South was so badly outnumbered and the burden was on the North to win the war, Lee’s grand strategy should have been a defensive one that did not squander the scarce manpower of the Confederacy.

Those supporting Lee’s aggressiveness sometimes fail to acknowledge that the Confederacy had advantages of its own. It consisted of a huge, 750,000-square mile territory which the Federals would have to invade and conquer. It also had the interior lines and was able to move its troops from place to place over shorter distances via a complex of well-placed railroads. The burden was on the North to win the war; a deadlock would confirm secession and the Confederacy. Historian James M. McPherson put it succinctly: “The South could ‘win’ the war by not losing; the North could win only by winning.” Concurring with that analysis was Southern historian Bell I. Wiley, who said: “ . . . the North also faced a greater task. In order to win the war, the . . . North had to conquer the South while the South could win by outlasting its adversary. . . . The South had reason to believe that it could achieve independence. That it did not be due as much, if not more, to its own failings as to the superior strength of the foe.”

The Confederates’ huge strategic advantage and their missed opportunities were confirmed by an early war analysis of the struggle by a military analyst writing in the Times of London. The analyst said, “ . . . It is one thing to drive the rebels from the south bank of the Potomac, or even to occupy Richmond, but another to reduce and hold in permanent subjection a tract of country nearly as large as Russia in Europe. . . . No war of independence ever terminated unsuccessfully except where the disparity of force was far greater than it is in this case. Just as England during the [American] revolution had to give up conquering the colonies, so the North will have to give up conquering the South.” The Confederate Secretary of War agreed with this view at the start of the war: “there is no instance in history of a people as numerous as we are inhabiting a country so extensive as ours being subjected if true to themselves.” Yet another Southern historian commented:

In the beginning, the Confederate leaders and most of the southern population believed the Confederacy had a strong prospect of success; many scholars today endorse this view… The Confederate war aim, which was to establish southern independence, was less difficult in the purely military sense than the Union war aim, which was to prevent the establishment of southern independence. The Confederacy could achieve its aim simply by protecting itself sufficiently to remain in existence. The Union could achieve its aim only by destroying the will of the southern population through invasion and conquest.

The South’s primary opportunity for success was to outlast Lincoln and the deep schisms among Northerners throughout the War made this a distinct possibility. Northerners violently disagreed on slavery, the draft, and the war itself. As early as May 1863, Josiah Gorgas noted in his journal the North’s susceptibility to a political defeat: “No doubt that the war will go on until at least the close of [Lincoln’s] administration. How many more lives must be sacrificed to the vindictiveness of a few unprincipled men! for there is no doubt that with the division of sentiment existing at the North the administration could shape its policy either for peace or for war.”

Confederate General Alexander confirmed the Confederacy’s need to wear down, not conquer, the North:

When the South entered upon war with a power so immensely her superior in men & money, & all the wealth of modern resources in machinery and transportation appliances by land & sea, she could entertain but one single hope of final success. That was, that the desperation of her resistance would finally exact from her adversary such a price in blood & treasure as to exhaust the enthusiasm of its population for the objects of the war. We could not hope to conquer her. Our one chance was to wear her out.

A Southern victory was not out of the question. After all, it had been only eighty years since the supposedly inferior American revolutionaries had vanquished the mighty Redcoats of King George III and it was less than fifty years since the outgunned Russians had repelled and destroyed the powerful invading army of Napoleon. The feasibility of such an outcome is demonstrated by the fact that, despite numerous crucial mistakes by Lee and others, the Confederates still appeared to have political victory in their grasp in the late summer of 1864, when Lincoln himself despaired of winning reelection that coming November.

Twice during the war, Lee went into the North on strategic offensives with scant chance of success, lost tens of thousands of irreplaceable officers and men in the disasters of Antietam and Gettysburg, and inevitably was compelled to retreat. These retreats enabled Lincoln to issue his crucial Emancipation Proclamation, created an aura of defeat that doomed any possibility of European intervention, and played a major role in destroying the South’s morale and will to fight. Finally, Lee’s offensive strategy and tactics so seriously weakened the Confederacy’s fighting capability that its defeat was perceived as inevitable by the time of the crucial 1864 presidential election.

It was Lee’s strategy and tactics that dissipated irreplaceable manpower—even in his “victories.” His tactical losses at Seven Days’ (especially Malvern Hill), his strategic defeats at Antietam and Gettysburg, and his costly “wins” at Second Bull Run and Chancellorsville—all in 1862 and 1863—made possible Grant’s and Sherman’s successful 1864 campaigns against the armies defending Richmond and Atlanta and created the aura of Confederate defeat that Lincoln exploited to win reelection. If Lee had performed differently, the North could have been fatally split on the war issue, Democratic nominee George B. McClellan might have defeated Lincoln, and the South could have negotiated an acceptable settlement with the compromising McClellan. Although some have contended that McClellan would not have allowed the South to remain outside the Union, he often had demonstrated both his reticence to engage in the offensive warfare necessary for the Union to prevail and his great concern about Southerners’ property rights in slaves. It would not have been out of character for McClellan to have sought a ceasefire immediately after the election and thereby have stopped Northern momentum and created a situation in which Southern independence was possible.

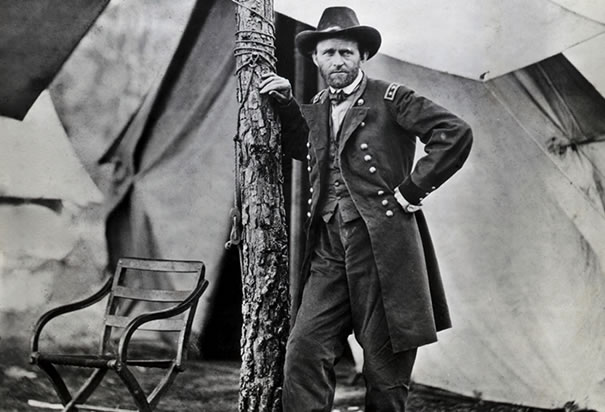

Northern victory affirmed the correctness of aggressiveness of Grant’s war strategy. Unlike most Union generals, who were reticent about taking advantage of the North’s numerical superiority and unwilling to invade the Confederacy that had to be conquered, Grant knew what had to be done and did it. Grant’s war-ending 1864 Overland Campaign against Lee’s army reflected Grant’s war-long philosophy that “The art of war is simple enough. Find out where your enemy is. Get at him as soon as you can. Strike him as hard as you can and as often as you can, and keep moving on.” Bruce Catton said it prosaically: “Better than any other Northern soldier, better than any other man save Lincoln himself, [Grant] understood the necessity for bringing the infinite power of the growing nation to bear on the desperate weakness of the brave, romantic, and tragically archaic little nation that opposed it. . . .”

General Cox said, “[Grant] reminds one of Wellington in the combination of lucid and practical common-sense with aggressive bull-dog courage.” In the words of T. Harry Williams, Grant “made his best preparations and then went in without reserve or hesitation and with a simple faith in success.” He advanced aggressively and creatively, and he attacked with vigor, but he usually avoided suicidal frontal attacks.

In light of a large number of battles fought by his armies, the total of 154,000 killed and wounded suffered by his commands was surprisingly small—especially when considered in light of the 209,000 killed and wounded among the soldiers commanded by Lee.

Examples of Grant’s war strategy include successful aggressiveness are numerous. He carried out his Belmont diversion in the vicinity of enemy forces several times his own. At the beginning of the Henry/Donelson campaign, in the words of Kendall Gott, “He landed a petty force of about 15,000 in the midst of nearly 45,000 enemy soldiers who could have massed against him.” His second-day counterattack at Shiloh turned stalemate or defeat into victory. His unexcelled Vicksburg Campaign into enemy territory where he was outnumbered marked the war’s turning point. His aggressiveness at

Chattanooga saved an army and set the stage for permanent victory in the middle theater. Finally, his aggressive Overland Campaign won the war in less than a year.

On the downside, Grant’s war strategy of aggressiveness caused him to focus so much on what he intended to do to the enemy that he at times became vulnerable to enemy surprises. Examples of these unexpected events were the initial Rebel breakout from Fort Donelson, the surprise Confederate attack on the first day at Shiloh, and Jubal Early’s 2nd Corps breaking free from the Grant-Lee deadlock in June 1864. His battlefield control and perseverance turned the first two events into major Union victories, and he was able to nullify Early’s foray because Lee kept Early in the eastern theater.

Not only did Grant’s war strategy recognize the need for the Union armies to be on the offensive, but he also was cognizant of the need for them to damage, destroy, or capture Confederate armies—instead of merely gaining control of geographic positions. He had, in Jean Edward Smith’s words, an “instinctive recognition that victory lay in relentlessly hounding a defeated army into surrender.” Only three armies surrendered while the Civil War raged: Buckner’s at Fort Donelson, Pemberton’s at Vicksburg, and Lee’s at Appomattox. They all surrendered to Grant in an affirmation that, as Albert Castel said, “ . . . he always sought, not merely to defeat, but to destroy the enemy.”

Grant’s War Strategy: Casualties

Wartime casualties need to be placed in the context of the populations of the North and South. At the outset of the war, the North had tremendous population and resource advantages over the South. The North had 22 million people, while the South had only nine million, of whom 3.5 million were slaves. Unless therefore the South found a way to fully involve those slaves in the war effort (and on the Confederate side), it faced a 4-to-1 general population disadvantage. More relevantly, the North had 4,070,000 men of fighting age (15 to 40), and the South had only 1,140,000 white men of fighting age. Considering that immigration and defecting slaves further augmented the North’s forces, the crucial bottom line is that the Union had an effective combat manpower advantage of 4:1 over the Confederacy. The South could not afford to squander its limited manpower.

Of the nearly three million men (two million Union and 750,000 Confederate) who served in the military during the war, 620,000 died (360,000 Union and 260,000 Confederate), 214,938 in battle and the rest from disease and other causes. While many Northerners were in the military for brief periods of time (many of them serving twice or more), most Southern military personnel were compelled to stay for the duration. Amazingly, almost one-fourth of Southern white males of military age died during the war—virtually all of them from wounds or war-related diseases. The primary point of all these statistics is that the South was greatly outnumbered and could not afford to squander its resource s by engaging in a war of attrition. Robert E. Lee’s deliberate disregard of this reality may have been his greatest failure. As James M. McPherson wrote, “For the war as a whole, Lee’s army had a higher casualty rate than the armies commanded by Grant. The romantic glorification of the Army of Northern Virginia by generations of Lost Cause writers has obscured this truth.”

The results of Lee’s faulty strategies and tactics were catastrophic. His army suffered almost 209,000 casualties—55,000 more than Grant and more than any other Union or Confederate Civil War general. Although Lee’s army inflicted a war-high 240,000 casualties on its opponents, about 117,000 of those occurred in 1864 and 1865 when Lee was on the defensive and Grant’s war strategy engaged in a deliberate war of adhesion (achieving attrition and exhaustion) against the army Lee had fatally depleted in 1862 and 1863. Astoundingly (in light of his reputation), Lee’s percentages of killed and wounded suffered by his troops were worse than those of his fellow Confederate commanders. During the first fourteen months that Lee commanded the Army of Northern Virginia (through the retreat from Gettysburg), he took the strategic and tactical offensive so often with his undermanned army that he lost 98,000 men while inflicting 120,000 casualties on his Union opponents.

The manpower-short Confederacy could not afford to trade numerous casualties with the enemy. During each major battle in the critical and decisive phase of the war from June 1862 through July 1863, Lee was losing an average 19 percent of his men while his manpower-rich enemies were suffering casualties at a tolerable 13 percent.

By 1864, therefore, Grant had a 120,000-man army and additional reserves to bring against Lee’s 65,000 and, by the sheer weight of his numbers, imposed a fatal 47 percent casualty rate on Lee’s army while losing a militarily tolerable 43 percent of his own replaceable men, as he drove from the Rappahannock to the James River and created a terminal threat to Lee’s army and Richmond. The high casualties sustained by Grant’s army in 1864 were substantial because “he was then under considerable political pressure to end the war quickly before the autumn presidential election.”

Had Lee not squandered Rebel resources during the three preceding years, the Confederacy’s 1864 opportunity for victory might have been realized. It was Lee’s strategy and tactics that dissipated irreplaceable manpower—even in his “victories.” His army lost at Malvern Hill, Antietam, Gettysburg, the Shenandoah Valley, Petersburg, and Appomattox. His army took unnecessarily high casualties in those defeats, as well as throughout the entire Seven Days’ Battle and at Chancellorsville. Lee’s army’s 1862–3 casualties made possible Grant’s successful 1864 campaign of adhesion to Lee’s army. Finally, the losses Lee’s army suffered at the Wilderness and Spotsylvania were higher than he could afford and helped to create the aura of Confederate defeat that Lincoln exploited to win reelection.

Fuller concluded, “If anything, Lee rather than Grant deserves to be accused of sacrificing his men.” Gordon Rhea similarly concluded that “Judging from Lee’s record, the rebel commander should have shared in Grant’s ‘butcher’ reputation.” James McPherson compared the casualties of Lee and Grant: “Indeed, for the war as a whole, Lee’s armies suffered a higher casualty rate than Grant’s (and higher than any other army). Neither general was a ‘butcher,’ but measured by that statistic, Lee deserved the label more than Grant.”

Far from being the uncaring slaughterer of men, Grant, again and again, displayed his feelings about the contributions of the ordinary soldier. After Chattanooga, for example, he alone raised his hat in salute to a ragged band of Confederate prisoners through which Union generals and their staffs were passing, and at Hampton Roads late in the war, he spoke to a group of Rebel amputees about better artificial limbs that were being manufactured.

A fresh and comprehensive analysis of all the casualties (killed, wounded, and missing/captured) in all of Grant and Lee’s campaigns and battles reinforces the brilliance of Grant’s accomplishments. Appendix II, “Casualties in Grant’s Battles and Campaigns,” contains a fairly exhaustive list of various historians’ and other authorities’ estimates of those casualties. This author has made the best estimate of the casualties and, at the end of that appendix, created a table of best estimates of those casualties for the entire war. While Grant’s armies were incurring a total of 153,642 casualties in those battles for which he was responsible and on which he had some effect, they were imposing a total of 190,760 casualties on the enemy. That positive total casualty differential of 37,118 should put to rest any negative analyses of Grant’s performance.

In their thought-provoking book, Attack and Die: Civil War Military Tactics and the Southern Heritage, Gordon McWhiney and Perry D. Jamieson provided some astounding numbers related to Grant’s major battles and campaigns. First, they determined that, in his five major campaigns and battles of 1862–3, he commanded a cumulative total of 220,970 soldiers and that 23,551 of them (11 percent) were either killed or wounded. Second, they determined that, in his eight major campaigns and battles of 1864–5 (when he was determined to defeat or destroy Lee’s army as quickly as possible), he commanded a cumulative total of 400,942 soldiers and that 70,620 of them (18 percent) were either killed or wounded. Third, they determined that during the course of the war, therefore, he commanded a cumulative total of 621,912 soldiers in his major campaigns and battles and that a total of 94,171 of them (a militarily tolerable 15 percent) were either killed or wounded.80 These loss percentages are remarkably low—especially considering the fact that Grant’s war strategy was on the strategic and tactical offensive in most of these battles and campaigns.

It may be helpful to put these numbers in perspective by comparing them to the casualty figures for the Army of Northern Virginia under Lee’s command and to those for other Confederate commanders. Incomplete figures show that Lee, in his major campaigns and battles, commanded a cumulative total of 598,178 soldiers, of whom 121,042 were either killed or wounded—a total loss of 20.2 percent, about one-third higher than Grant. Other major Confederate commanders with higher percentages killed or wounded than Grant were Generals Braxton Bragg (19.5 percent), John Bell Hood (19.2 percent), and Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard (16.1 percent).

Similarly, Lee’s generals were mortally wounded in battle at a much higher rate than those under other Confederate commanders. After Lee took command of the Army of Northern Virginia, he lost two of the three mortally wounded Confederate lieutenant generals (corps commanders), four of the seven mortally wounded Confederate major generals (division commanders), and 33 of 53 mortally wounded Confederate brigadier generals (brigade commanders). McWhiney and Jamieson also tallied those Civil War battles in which either side incurred the heaviest percentage of losses suffered by one side during the entire war. Of the nineteen battles in which one side lost nineteen percent or more of its troops (killed or wounded), only “one” involved such a loss by Grant’s troops (and that was actually two battles—29.6 percent at Wilderness and Spotsylvania combined). Given the number of battles Grant’s armies fought, this is a surprising, but informative, result. Contrarily, Lee’s army suffered the highest percentage of such losses in a single battle at Gettysburg (30.2 percent) and the fifth and seventh highest such losses at Antietam (22.6 percent) and Seven Days’ (20.7 percent).

Writing in 1898, Charles Dana, Assistant Secretary of War during the Civil War, analyzed this facet of Grant’s Overland Campaign: “There are still many persons who bitterly accuse Grant of butchery in this campaign. As a matter of fact, Grant’s war strategy lost fewer men in his successful effort to take Richmond and end the war than his predecessors lost in making the same attempt and failing.” Dana examined the specific casualties suffered by Union troops in the East under Grant’s predecessors and then under Grant. Under Generals McDowell, McClellan, Pope, Burnside, Hooker, and Meade, the Union’s eastern armies, according to Dana’s table of statistics, had 15,745 killed, 76,079 wounded, and 52,101 missing or captured for a total of 143,925 casualties between May 24, 1861, and May 4, 1864. He then calculated Grant’s losses between May 5, 1864, and April 9, 1865, as 15,139 killed, 77,748 wounded, and 31,503 missing or captured for a total of 124,390. Dana concluded that these numbers showed that “Grant in eleven months secured the prize with less loss than his predecessors suffered in failing to win it during a struggle of three years.”

This article is part of our larger selection of posts about the Civil War. To learn more, click here for our comprehensive guide to the Civil War.

Cite This Article

"Grant’s War Strategy That Made 3 Confederate Armies Surrender" History on the Net© 2000-2024, Salem Media.

July 27, 2024 <https://www.historyonthenet.com/grants-war-strategy-that-made-3-confederate-armies-surrender>

More Citation Information.